Social Democracy After the Cold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Ecosy Congress

10 TH ECOSY CONGRESS Bucharest, 31 March – 3 April 2011 th Reports of the 9 Mandate ECOSY – Young European Socialists “Talking about my generation” CONTENTS Petroula Nteledimou ECOSY President p. 3 Janna Besamusca ECOSY Secretary General p. 10 Brando Benifei Vice President p. 50 Christophe Schiltz Vice President p. 55 Kaisa Penny Vice President p. 57 Nils Hindersmann Vice President p. 60 Pedro Delgado Alves Vice President p. 62 Joan Conca Coordinator Migration and Integration network p. 65 Marianne Muona Coordinator YFJ network p. 66 Michael Heiling Coordinator Pool of Trainers p. 68 Miki Dam Larsen Coordinator Queer Network p. 70 Sandra Breiteneder Coordinator Feminist Network p. 71 Thomas Maes Coordinator Students Network p. 72 10 th ECOSY Congress 2 Held thanks to hospitality of TSD Bucharest, Romania 31 st March - 3 rd April 2011 9th Mandate reports ECOSY – Young European Socialists “Talking about my generation” Petroula Nteledimou, ECOSY President Report of activities, 16/04/2009 – 01/04/2011 - 16-19/04/2009 : ECOSY Congress , Brussels (Belgium). - 24/04/2009 : PES Leaders’ Meeting , Toulouse (France). Launch of the PES European Elections Campaign. - 25/04/2009 : SONK European Elections event , Helsinki (Finland). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 03/05/2009 : PASOK Youth European Elections event , Drama (Greece). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 04/05/2009 : Greek Women’s Union European Elections debate , Kavala (Greece). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 07-08/05/2009 : European Youth Forum General Assembly , Brussels (Belgium). - 08/05/2009 : PES Presidency meeting , Brussels (Belgium). - 09-10/05/2009 : JS Portugal European Election debate , Lisbon (Portugal). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. -

Writ of Certiorari Appendix

No. 08-___ IN THE RUBEN CAMPA, RENE GONZALEZ, ANTONIO GUERRERO, GERARDO HERNANDEZ, AND LUIS MEDINA, Petitioners, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Respondent. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit APPENDIX TO THE PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI Leonard I. Weinglass Thomas C. Goldstein 6 West 20th Street Counsel of Record New York, NY 10011 Christopher M. Egleson Won S. Shin Michael Krinsky AKIN, GUMP, STRAUSS, 111 Broadway HAUER & FELD LLP Suite 1102 1333 New Hampshire New York, NY 10006 Ave., NW Washington, DC 20036 Counsel to Petitioner (202) 887-4000 Guerrero Additional counsel listed on inside cover Paul A. McKenna Richard C. Klugh, Jr. 2910 First Union Ingraham Building Financial Center 25 S.E. 2nd Avenue 200 South Biscayne Blvd. Suite 1105 Miami, FL 33131 Miami, FL 33131 Counsel to Petitioner Counsel to Petitioner Hernandez Campa William N. Norris Philip R. Horowitz 8870 S.W. 62nd Terrace Two Datran Center Miami, FL 33173 Suite 1910 9130 South Dadeland Counsel to Petitioner Blvd. Medina Miami, FL 33156 Counsel to Petitioner Gonzalez TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit Opinion (June 4, 2008) .................... 1a U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit (En Banc) Opinion (August 9, 2006) ........................................................... 90a U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit Opinion (August 9, 2005)............. 220a U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida Order (July 27, 2000) ......................................................... 319a U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida Order (October 24, 2000) ........................................................ -

Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent Kenneth C

Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent Kenneth C. Dewar Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d'études canadiennes, Volume 53, Number/numéro 1, Winter/hiver 2019, pp. 178-196 (Article) Published by University of Toronto Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/719555 Access provided by Mount Saint Vincent University (19 Mar 2019 13:29 GMT) Journal of Canadian Studies • Revue d’études canadiennes Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent KENNETH C. DEWAR Abstract: This article argues that the lines separating different modes of thought on the centre-left of the political spectrum—liberalism, social democracy, and socialism, broadly speaking—are permeable, and that they share many features in common. The example of Tom Kent illustrates the argument. A leading adviser to Lester B. Pearson and the Liberal Party from the late 1950s to the early 1970s, Kent argued for expanding social security in a way that had a number of affinities with social democracy. In his paper for the Study Conference on National Problems in 1960, where he set out his philosophy of social security, and in his actions as an adviser to the Pearson government, he supported social assis- tance, universal contributory pensions, and national, comprehensive medical insurance. In close asso- ciation with his philosophy, he also believed that political parties were instruments of policy-making. Keywords: political ideas, Canada, twentieth century, liberalism, social democracy Résumé : Cet article soutient que les lignes séparant les différents modes de pensée du centre gauche de l’éventail politique — libéralisme, social-démocratie et socialisme, généralement parlant — sont perméables et qu’ils partagent de nombreuses caractéristiques. -

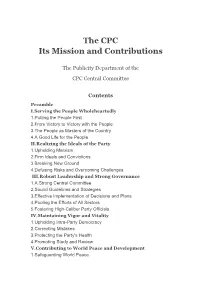

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions The Publicity Department of the CPC Central Committee Contents Preamble I.Serving the People Wholeheartedly 1.Putting the People First 2.From Victory to Victory with the People 3.The People as Masters of the Country 4.A Good Life for the People II.Realizing the Ideals of the Party 1.Upholding Marxism 2.Firm Ideals and Convictions 3.Breaking New Ground 4.Defusing Risks and Overcoming Challenges III.Robust Leadership and Strong Governance 1.A Strong Central Committee 2.Sound Guidelines and Strategies 3.Effective Implementation of Decisions and Plans 4.Pooling the Efforts of All Sectors 5.Fostering High-Caliber Party Officials IV.Maintaining Vigor and Vitality 1.Upholding Intra-Party Democracy 2.Correcting Mistakes 3.Protecting the Party's Health 4.Promoting Study and Review V.Contributing to World Peace and Development 1.Safeguarding World Peace 2.Pursuing Common Development 3.Following the Path of Peaceful Development 4.Building a Global Community of Shared Future Conclusion Preamble The Communist Party of China (CPC), founded in 1921, has just celebrated its centenary. These hundred years have been a period of dramatic change – enormous productive forces unleashed, social transformation unprecedented in scale, and huge advances in human civilization. On the other hand, humanity has been afflicted by devastating wars and suffering. These hundred years have also witnessed profound and transformative change in China. And it is the CPC that has made this change possible. The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history dating back more than 5,000 years, China has made an indelible contribution to human civilization. -

DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS

·Legislative Assembly Of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Speaker· The Honourable A. W. Harrison VolUitJ.e Irt No. 7 June 17. 1959 lst Session, 26th Legislature Printed by R. S. Evans, Queen's Printer for the Province of Manitoba, Winnipeg INDEX Wednesday, June 17, 1959, 2:30 P .M. � Introduction of Bills, No. 60, Mr. Scarth ................................... .. 83 Questions ..•.•...•.. .. ..••...••....•.•..•.•..•.......•••.......•......... 83 Mr. Orlikow (Mr. McLean) Mr. Harris (Mr. Roblin) Mr. Paulley (Mr. Roblin) Mr. Gray (Mr. Johnson) Mr. Roberts (Mr. Lyon). Mr. Paulley, (Mr. Thompson) . Mr. Hryhorczuk (Mr. Lyon). BillNo. 30, Second Reading, re Anatomy Act (Mr. Johnson) 84 Questions' Mr. Gray, Mr. Paulley, Mr. Molgat. BillNo. 31, Second Reading, re PracticalNurses Act 85 (Mr. Johnson) Speech From the Throne, debate. Mr. Orlikow . • . .. • . ... .. • . • • . • . 86 Mr. Lyon . • . • • . • . • . • . • . • . • . • • . • . •• • . • • 92 Mr. Gray, Mr. Lyon, Mr. Schreyer • • . • . • . • . 96 Division, Amendment to theAmendment, Throne Speech 98 Adjourned Debate, Mr. Gray's Motion re Pensioners. Mr. Guttormson, amendment . • . • • • . • . • • . • . 99 Proposed Resolution, Mr. Paulley, re Compulsory Insurance . • . • . • . 100 Mr. Evans, Mr. Hillhouse, Mr. Paulley .. .... .. .. .. ... • .. ... .. • . .. • 103 Mr. McLean, Mr. Hillhouse, Mr. Paulley . • . • . • . .. 104 Proposed Resolution, Mr. Ridley, re Farm Implement Tax . • . • • . • . • . • . 105 THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF MANITOBA 2:30 o'clock, Wednesday, June 17th, 1959 Opening Prayer by Mr. Speaker. MR. SPEAKER: Presenting Petitions Reading and Receiving Petitions Presenting Reports by Standing and Select Committees Notice of Motion Introduction of Bills MR. W. B. SCARTH, Q: C. (River Heights) introduced Bill No. 60, an Act to amend The Greater Winnipeg Water District Act. COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE HOUSE HON, GuRNEY EVANS (Minister of Mines and Natural Resources) (Fort Rouge): In the absence of the Minister of Public Works I wonder if the House would agree to allow this item to stand. -

Now British and Irish Communist Organisation

THE I C PG ·B NOW BRITISH AND IRISH COMMUNIST ORGANISATION From its foundation until the late 1940s, the Communist Party of Great Britain set itself a very clear political task - to lead the British working class. Its justification was that the working class required the abolition of capitalism for its emancipation, and only the Communist Party was able and willing to lead the working class in undertaking this. l'he CP recognised that it might have to bide its time before a seizure of power was practicable, mainly, it believed, because the working class .' consciousness was not yet revol utionary. But its task was still to lead the working class: only by leading the working class in the immediate, partial day-to-day class struggle could the CP hope to show that the abolition of capitalism was the real solution to their griev ances. It was through such struggle that the proletariat would learn; and without the Communist Party to point out lead the Left of the Labour Party to abolish c~pitalism: The 'll lacked the vital understand~ng and w~ll to the lessons of the struggle, the proletariat would draw only Labour Party s t 1 . · partial and superficial conclusions from its experience. · L ft Labour was open to Commun~st 1nf1 uence. do th~s. But e h · ld cooperate with the Labour Party because t e Commun~sts cou , h d h By the mid-1930s, the Communist Party was compelled to ack · 't f the Labour Party s members also a t e vast maJor~ Y o 1 nowledge that the Labour Party had gained the allegiance of . -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Why Some People Switch Political Parties: New Research 13 July 2021, by Paul Webb and Tim Bale

Why some people switch political parties: New research 13 July 2021, by Paul Webb and Tim Bale Our new research sheds light on the truth of party- switching politics—how many people really switch, why people are motivated to do so, and whether the claims of entryism are credible. Patterns of party-switching We surveyed nearly 7,000 members of British political parties (including registered Brexit Party supporters) within two weeks of the 2019 general election. When we analyzed the data, we found a remarkably high proportion of our sample (23%) claimed to have previously been—or, if we allow for registered Brexit Party supporters as well, currently were—members of a different political party than the Credit: CC0 Public Domain one to which they were now affiliated. Some 29% of Tory members who admitted in 2019 to having been members of other parties claim to Why do some people switch political parties? After have been UKIP members. Interestingly, though, all, if someone is committed enough to a particular virtually as many were former Labor members. As a vision of politics, wouldn't they be relatively proportion of all Conservative Party grassroots immune to the charms of its competitors? members, these figures amount to 3% who were former members of UKIP, 4.5% who were It turns out, however, that switching parties at simultaneously Brexit Party supporters, and 4% grassroots membership level is by no means who were ex-Labor members. uncommon, even giving rise in some quarters to accusations of "entryism." This puts into perspective the scale of the entryist phenomenon. -

New Horizons Preface

TEN CENTS NEW HORIZONS PREFACE This 1>amphlet is ba~:>ed on the speech made by Pro fessor F. R. Scott to the 11th CCF National Conventicm, in Vancouver, JuZ.y, 1950, when he relinquished the position of National Chairm-an after foU'r successive terms. F. R. Scott is professor of civil law at McGill Univer sity and a widely-recognized e.rpert on the Canadian con stitndion. He was prominent among those who O'rgamized the League fo1· Social Reconst?"'ztction in the early thirties, and collaborated in the LSR's writing and publication of "Social Planning for Canada" and "Democracy Needs Socialism." He attended the fi·rst CCF National Conve.ntian in Regina, in 1933, and helped to draft the Regina Mani festo. In 1942, together with David Lewis, he wrote "Make This Your Ca?WAla," until then the most comp'rehensive statement of CCF history and policies. Professo?· Scott is at present a member of the CCF National Council and Executive. NEW HORIZONS FOR SOCIALISM GfT Regina, in 19JJ, the GCF Party held its first national convention, and drew up the basic statement of its philosophy and program which has been known ever since as the Regina Manifesto. Probably no other document in Canadian political history has made so deep an impression on the mind of its generation, M secured so sure a place in our public annals. Certainly within the CCF itself the Regina Manifesto holds an especially honoured position. In the depth of its analysis of capitalism, the vig.aur of its denunciation of the injustices of Canadian society, Page one and the clarity with which it distinguished democratic socialism from the liberal economic theories of the old-line parties, it pro vided for every party member a chart and compass by which to steer through the stormy seas of political controversy. -

Laarly 100 Auandad National Antiwar Convenuon in L.A. Protests Against Bombing Ol Dikes Sailor Aug.5-9

! (,'I I I. AUGUST 4, 1972 25 CENTS A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE laarly 100 auandad national antiwar convenuon In L.A. Protests against bombing ol dikes sailor Aug.5-9. ..__ By NORTON SANDLER from the West Coast, but there were approved by the overwhelming ma An effort by some McGovern sup and HARRY RING individuals and delegations from 23 jority of the gathering, recommended porters to have the conference com LOS ANGELES- The national anti states. that NPAC maintain its nonpartisan mit itself to supporting McGovern's war co~rence held here July 21-23 Convention organizers vie~ed ·the stand toward the elections. This stand presidential bid sparked heated debate voted to organize nationwide demon gathering as a major· gain for anti is essential, the proposal declared, if on NPAC's nonpartisan electoral· strations against the· Vietnam war 9n war forces. They regarded the atten NPAC is to continue to organize mas stand. Oct 26 and Nov. 18. The convention, dance as very good for the first na sive street demonstrations against the Originally, some McGovern support tional antiwar conference to be held called by the National Peace Action war. ers considered presenting a resolution Coalition (NPAC), also ratified plans on the West Coast, particularly since The proposal recognized that NPAC calling for the conference to endorse it took place in midsummer. It also for making the Aug. 5-9 Hiroshima embraces a broad range of political their candidate. Recognizing there was . Nagasaki commemorative demonstra came within two weeks of the Dem views. -

Ett Oavvisligt Allmän- Intresse Om Mediedrev Och Politiska Affärer

ETT OAVVISLIGT ALLMÄN- INTRESSE OM MEDIEDREV OCH POLITISKA AFFÄRER Stefan Wahlberg 08.04.17 ETT OAVVISLIGT ALLMÄNINTRESSE, RAPPORT, TIMBRO 2008 INNEHÅLL 1. Inledning 3 2. Den politiska affärens båda sidor 4 2.1 Medierna som den politiska affärens katalysator 4 3. Sahlinaffären och dataintrångsaffären 6 3.1 Sahlinaffären i sammanfattning 6 3.2 Dataintrångsaffären i sammanfattning 8 4. Publicitetens omfattning och fördelning över tid 10 4.1 Sahlinaffären 10 | 4.1.1 Affärens första månad 10 | 4.1.2 Affärens första år 11 4.2 Dataintrångsaffären 11 | 4.2.1 Affärens första månad 11 | 4.2.2 Affärens första år 12 4.3 Den mediala dramaturgin utifrån publicitetens omfattning och fördelning i tid 12 4.3.1 Anslag och kulmen 12 | 4.3.2 Avtoning – hur dör en politisk affär? 13 4.3.3 Elva år – ett nytt och snabbare medielandskap 14 5. Mediedrevens explosioner – och saktfärdighet 15 5.1 I väntans tider eller spurt från första början 15 6. Den rättsliga hanteringen 17 6.1 Lag och rätt i Sahlinaffären 17 6.2 Lag och rätt i dataintrångsaffären 18 6.3 Rättsväsendets publika agerande under affärerna 19 6.4 Rättsväsendet – med full tillit från medierna 21 6.4.1 Juridiska bedömningsfrågor i Sahlinaffären 21 6.4.2 Fullt pådrag hos polisen i dataintrångsaffären 23 7. Kärringarna mot strömmen – de var få i båda affärerna 25 7.1 Några utmärkande undantag 25 | 7.1.1 Sahlinaffären 26 | 7.1.2 Dataintrångsaffären 27 8. Finns det något facit – vad är rätt och vad är fel? 29 8.1 Mona Sahlins Diners Club-kort – spärrat eller inte? 30 9. -

Estrategias Electorales De La Izquierda Canadiense En Un Sistema Que Favorece Al Bipartidismo Santín Peña, Oliver

www.ssoar.info Estrategias electorales de la izquierda canadiense en un sistema que favorece al bipartidismo Santín Peña, Oliver Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Santín Peña, O. (2017). Estrategias electorales de la izquierda canadiense en un sistema que favorece al bipartidismo. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, 62(231), 77-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0185-1918(17)30039-9 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-58623-1 Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales⎥ Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Nueva Época, Año LXII, núm. 231 ⎥ septiembre-diciembre de 2017 ⎥ pp. 77-106⎥ ISSN-2448-492X Estrategias electorales de la izquierda canadiense en un sistema que favorece al bipartidismo Electoral Strategies of the Canadian Left in A Predominantly Two-Party System Oliver Santín Peña∗ Recibido: 11 de mayo de 2016 Aceptado: 2 de mayo de 2017 RESUMEN ABSTRACT Este trabajo tiene como objetivo analizar el This paper aims to analyze the origin, develop- origen, desarrollo y estrategias de la izquier- ment and strategies of the Canadian party-based da partidista canadiense y su evolución como left and its evolution as a political group to com- grupo político para contender en elecciones fe- pete in federal elections.