Final Format Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January/February 2014 Vol

The Gainesville Iguana January/February 2014 Vol. 28, Issue 1/2 CMC SpringBoard fundraiser March 21 by Joe Courter The date for the Civic Media Center’s annual SpringBoard fundraiser is Friday evening, March 21. There will be a new location this year after last year’s venture at Prairie Creek Lodge, and that is in the heart of Down- town Gainesville at the Wooly, 20 N. Main St., a new event venue in what is the old Woolworth building next to and run by The Top restaurant. There will be food from various area restaurants, a si- lent auction and raffle items, and awards. The speaker this year is an old friend of McDonald’s workers and allies strike on July 31, 2013 in Chicago. Photo by Steve Rhodes. the CMC, David Barsamian, the founder and main man with Alternative Radio, who said he is “honored to follow in No- 2013 in review: Aiming higher, am’s footsteps.” labor tries new angles and alliances That is fitting because Alternative Ra- by Jenny Brown ment that jobs that once paid the bills, dio has made a special effort to archive from bank teller to university instructor, Noam Chomsky talks since its founding This article originally appeared in the now require food stamps and Medicaid to in 1989. David’s radio show was a staple January 2014 issue of LaborNotes. You supplement the wages of those who work See SPRINGBOARD, p. 2 can read the online version, complete with informative links and resources, at www. every day. labornotes.org/2013/12/2013-review- California Walmart worker Anthony INSIDE .. -

The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing Academic Programs and Advising 2020 The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot Adam Clark Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/studentawards Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Adam, "The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot" (2020). Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing. 16. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/studentawards/16 This Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Programs and Advising at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adam Clark Victoria Malawey, Gender & Music The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot “We’re gonna take over the punk scene for feminists” -Kathleen Hanna Although they share feminist ideals, the Russian art collective Pussy Riot distinguishes themselves from the U.S.-based Riot Grrrl Movement, as exemplified by the band Bikini Kill, because of their location-specific protest work in Moscow. Understanding how Pussy Riot is both similar to and different from Riot Grrrl is important for contextualizing the way we think about diverse, transnational feminisms so that we may develop more inclusive and nuanced ways in conceptualizing these feminisms in the future. While Pussy Riot shares similar ideals championed by Bikini Kill in the Riot Grrrl movement, they have temporal and location-specific activisms and each group has their own ways of protesting injustices against women and achieving their unique goals. -

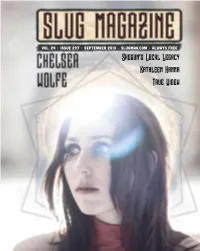

Shogun's Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow

Vol. 24 • Issue 297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com • Always Free Shogun’s Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow slugmag.com 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround slugmag.com 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 24 • Issue #297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com facebook.com/SLUG.Mag @SLUGMag @SLUGMag youtube.com/user/SLUGMagazine Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Manager: Editor: Angela H. Brown Karamea Puriri Managing Editor: Esther Meroño Marketing Team: Ischa B., Sabrina Costello, Editorial Assistant: Alexander Ortega Kristina Sandi, Brooklyn Ottens, Angella Luci- Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan sano, Nicole Roccanova, Raffi Shahinian, Vic- Digital Content Coordinator: Cody Kirkland toria Loveless, Zac Freeman, Cassie Anderson, Copy Editing Team: Esther Meroño, Alexan- Cassie Loveless, Shley Kinser, Matt Brunk, Robin der Ortega, Mary E. Duncan, Cody Kirkland, Sessions, Carl Acheson, Chandler Hunt Johnathan Ford, Alex Cragun, Rachel Miller, Ka- Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer tie Bald, Liz Phillips, Allison Shephard, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Shawn Soward Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Tony Cover Designer: Joshua Joye Bassett, Nancy Burkhart, Adam Okeefe, Ryan Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Worwood, John Ford, Matt Pothier, Phil Cannon, Design Team: Eleanor Scholz, BJ Viehl, Lenny Tim Kronenberg, Justin Nelson-Carruth, Xkot Riccardi, Chad Pinckney, Mason Rodrickc Toxsik, Nancy Perkins Ad Designers: Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Christian Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Eric Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, Mariah Sapp, Brad Barker, Paden Bischoff, Maggie Mann-Mellus, James Orme, Lance Saunders, Zukowski, Thy Doan, KJ Jackett, Nicholas Dowd, Bryer Wharton, Peter Fryer, James Bennett, Ricky Nick Ketterer Vigil, Gavin Hoffman, Esther Meroño, Rebecca Website Design: Kate Colgan Vernon, Jimmy Martin, Ben Trentelman, Princess Office Interns: Carl Acheson, Robin Sessions, Kennedy, Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Cody Hudson, Alex Cragun, Chandler Hunt Shawn Mayer, Dean O. -

The Art Worlds of Punk-Inspired Feminist Networks

! The Art Worlds of Punk-Inspired Feminist Networks ! ! ! ! ! ! A social network analysis of the Ladyfest feminist music and cultural movement in the UK ! ! ! ! ! ! A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities ! ! ! 2014 ! ! Susan O’Shea ! ! School of Social Sciences ! ! Chapter One Whose music is it anyway? 1.1. Introduction 12 1.2. Ladyfest, Riot Girl and Girls Rock camps 14 1.2.1. Ladyfest 14 1.2.2. Riot Grrrl 16 1.2.3. Girls Rock camps 17 1.3. Choosing art worlds 17 1.4. The evidence: women’s participation in music 20 1.5. From the personal to the political 22 1.6. Thesis structure 25 Chapter Two The dynamics of feminist cultural production 2.1. Introduction 27 2.2. Art Worlds and Becker’s approach 29 2.3. Punk, Riot Grrrl and Ladyfest 32 2.3.1. Punk 33 2.3.2. Riot Grrrl 34 2.3.3. Ladyfest 40 2.4. The political economy of cultural production 41 2.5. Social movements, social networks and music 43 2.6. Women in music and art and the translocal nature of action 48 2.6.1. Translocality 50 2.7. Festivals as networked research sites 52 2.8. Conclusion 54 Chapter Three Methodology 3.1. Introduction 56 !2 ! 3.2. Operationalising Art Worlds, research aims and questions 57 3.3. Research philosophy 58 3.4. Concepts and terminology 63 3.5. Mixed methods 64 3.6. Ethics 66 3.6.1. Ethics review 68 3.6.2. -

The Untold Stories of Riot Grrrl Critics and Revolutionists

“Wait a Minute, There’s a Sister in There?” The Untold Stories of Riot Grrrl Critics and Revolutionists by Katherine Ross Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Sociology) Acadia University Spring Convocation 2018 © by Katherine Ross, 2017 This thesis by Katherine Ross was defended successfully in an oral examination on 17th November 2017. The examining committee for the thesis was: ________________________ Dr. Anna Redden, Chair ________________________ Dr. Riley Chisholm, External Examiner ________________________ Dr. Sarah Rudrum, Internal Reader ________________________ Dr. Saara Liinamaa, Supervisor _________________________ Dr. Jesse Carlson, Acting Head This thesis is accepted in its present form by the Division of Research and Graduate Studies as satisfying the thesis requirements for the degree Master of Arts (Sociology). …………………………………………. ii I, Katherine Ross, grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to reproduce, loan or distribute copies of my thesis in microform, paper or electronic formats on a non-profit basis. I, however, retain the copyright in my thesis. _________________________________ Author _________________________________ Supervisor _________________________________ Date iii Table of Contents ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................... vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................... vii CHAPTER -

Anarchism, Hardcore Music, and Counterculture

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2016 Don't Let the World Rot: Anarchism, Hardcore Music, and Counterculture Pearson Bolt University of Central Florida Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Ethnomusicology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Bolt, Pearson, "Don't Let the World Rot: Anarchism, Hardcore Music, and Counterculture" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5128. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5128 DON’T LET THE WORLD ROT: ANARCHISM, HARDCORE, AND COUNTERCULTURE by PEARSON L. BOLT B.A. University of Central Florida, 2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2016 Major Professor: Anthony Grajeda © Pearson Bolt 2016 ii ABSTRACT Hardcore music is intrinsically anarchistic. The hardcore music scene represents a radical departure from contemporary society. Rejecting the materialism, militarism, and hedonism of the mainstream music scene—and, by extension, modern culture—hardcore music presents an alternative lifestyle rooted in solidarity, equality, and liberty. Indeed, the culture of the hardcore scene approaches a transitive, nomadic model of an anarchistic commune built on resistance as a way of life. -

100 JAHRE FRAUENWAHLRECHT Filme Und Medien Von Und Über Frauen

100 JAHRE FRAUENWAHLRECHT Filme und Medien von und über Frauen Auswahlbiblio- und fi lmographie EINLEITUNG Vor 100 Jahren wurde nach langem feministischem Ringen um Emanzipation und Gleichstellung am 12. November 1918 das Frauenwahlrecht in Deutschland gesetzlich verankert. Frauen in Deutschland erhielten somit das aktive und passive Wahlrecht. Das Digitale Deutsche Frauenarchiv – DDF erstellte zum 100jährigen Bestehen des Frauenwahlrechts eine digitale Ausstellung, die seit September 2018 zu sehen ist. Das Online-Portal www.digitales-deutsches-frauenarchiv.de macht die Geschichte der deutschen Frauenbewegung digital für alle verfügbar. Dabei wird die Geschichte der Frauenbewegungen anhand ausgewählter Materialien – vom Tagebuch bis zum Notenblatt, vom Plakat bis zur Zeitschrift erzählt, und blickt nicht nur auf Frauengeschichte zurück, sondern fragt zudem, welche Aktionen und Themen Frauen heute bewegen. Die Cinemathek der Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin (ZLB) präsentiert anlässlich der 100 Jahre Frauenwahlrecht gemeinsam mit dem Fachbereich Historischen Sammlungen Filme und Medien zum Frauenwahlrecht aus unserem Bestand. In Ergänzung dazu geben wir Einblick in Filme und andere Medien von und über Frauen. © 2018 i.d.a. Dachverband deutschsprachiger Frauen / Lesbenarchive, Foto: N.N., Gruppenbild Atelier Elvira, um 1894, -bibiliotheken und -dokumentationsstellen Quelle: https://de.wikipedia.org Quelle: digitales-deutsches-frauenarchiv.de_neu.svg 2 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Einleitung 3 Stummfilme 3 Tonspielfilme 3 Fernsehserien 6 Dokumentarfilme 7 Musik 8 Auswahlbibliographie zum Frauenstimmrecht und zur Frauenbewegung 9 Webressourcen 12 Veranstaltungen 13 Impressum 14 2 STUMMFILME Anna Müller-Lincke kandidiert. Regie: Werner Sinn. Deutschland 1919. Video-Stream: https://weimar.bundesarchiv.de/WEIMAR/DE/Content/Artikel/ Fokusthema/2018-03-16_anna-mueller.html Vier Filme mit Asta Nielsen. Orig.: Deutschland, 1913 – 1916. München: Film & Kunst, 2012. -

Read the Following Text and Answer the Questions. the Riot

Read the following text and answer the questions. The riot grrrl returns Dan Hancox – October 3, 2013 – The National Among the various waves of western feminism and rebellious youth subcultures since the 1960s, riot grrrl stands out as one of the most provocative, but also one of the most thoughtful and deliberative. Its roots were in the punk and new wave music and attitude of the late 1970s and 1980s, but it was not until the early 1990s that the term emerged from the punk scenes of Washington DC and the north-western region of the United 5 States, drawing on a growing youth feminist movement and the DIY youth culture embodied in homemade, cut-and-paste fanzines. References to “revolution girl style now” and “riot girls” mutated into the punk growl not of docile girls but “grrrls”. It was quickly and substantially misunderstood by the very culture they were rebelling against: as bands like Bikini Kill and Bratmobile began to attract attention beyond the punk underground, so did the American 10 media’s excitement about this “new big thing”, in the aftermath of grunge. This excitement quickly manifested itself in a tendency to generalise, fetishise and trivialise the things the riot grrrls were singing about, and conveying through their broader aesthetics: in fanzines, onstage, or otherwise. “There were,” Sharon Cheslow said in the 11-part Riot Grrrl Retrospective documentary, “a lot of very important ideas that I think the mainstream media couldn’t handle, so it was easier to focus on the fact that these were girls who 15 were wearing barrettes in their hair or writing ‘slut’ on their stomach.” Covering issues like misogyny, abuse and patriarchy were considered too contentious or complex for the American mainstream, and instead, the movement was patronised in a way which confirmed much of their original anger. -

Representing Riot Grrrl David Buckingham This Essay Is Part of A

Real girl power? Representing riot grrrl David Buckingham This essay is part of a larger project, Growing Up Modern: Childhood, Youth and Popular Culture Since 1945. More information about the project, and illustrated versions of all the essays can be found at: https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/. It’s now a quarter of a century since the media began announcing the death of riot grrrl. The movement did not last very long – although as is often the case, some people maintain that it has never died, while others claim to detect periodic signs of revival. Certainly, there are few under the age of forty who are likely to have heard of it. Yet arguably, riot grrrl continues to exercise an influence that has been much more lasting than its relatively short life-span would suggest. The thumbnail history would run something like this. Riot grrrl was an explicitly feminist youth movement that emerged from the US post-punk and hardcore scenes. It was born in early 1991 in the small college town of Olympia in Washington State, USA; although it wasn’t named until later that year, when members of two key bands, Bikini Kill and Bratmobile, were staying on a summer break in Washington DC. The movement was consolidated back in Olympia in August of that year when these and other female-only (or female-led) bands played at a ‘girl night’, which opened the International Pop Underground Convention. From these origins, riot grrrl became a national movement, spread both by coverage in the mainstream media and by a proliferation of ‘zines’ published and distributed in informal networks right across the United States, and eventually elsewhere. -

Race and Riot Grrrl: a Retrospective

Race and Riot Grrrl: A Retrospective What is Riot Grrrl? - Riot Grrrl is an international underground feminist movement (mainly youth oriented) that initially emerged from the West Coast American alternative and punk music scenes. - It began in Olympia, Washington and was most active between 1989 and 1997. - The movement produced bands like Heavens to Betsy, Bratmobile and Bikini Kill. Bikini Kill’s lead singer, Kathleen Hanna, is typically thought of as being the founder and voice of the movement though she would later claim she only played a small part. - Riot Grrrl was heavily influenced by the Queercore scene (another offshoot of punk whose lyrics explored themes of prejudice against the LGBT community). Riot Grrrl was characterized by its similarly aggressive style and overtly political/controversial lyrics. - Riot Grrrls were performers as well as activists and publishers. They held regular meetings and national conferences similar to the feminist discussion and support groups of the 1960s and 1970s that allowed women to meet and discuss music as well as their experiences of sexism, body image and identity. - The movement also used zines (or small D.I.Y. magazines) as its primary method of communication. Thousands of young women began to produce personal and political zines with explicitly feminist themes, which allowed Riot Grrrl to spread its message without the use of mainstream media. The Punk Singer (2013, Sini Anderson) Influential Riot Grrrl Bands 7 Year Bitch Babes in Toyland Bikini Kill Bratmobile Heavens to Betsy Huggy Bear L7 Sleater-Kinney Bikini Kill - Rebel Girl The “Other” History of Riot Grrrl “With riot grrrl now becoming the subject of so much retrospection, I argue that how the critiques of women of color are narrated is important to how we remember feminisms and how we produce feminist futures. -

Bad Reputation

Presents BAD REPUTATION A film by Kevin Kerslake 95 mins, USA, 2018 Language: English Distribution Publicity Mongrel Media Inc Bonne Smith 1352 Dundas St. West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Twitter: @starpr2 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com SHORT SYNOPSIS A look at the life of Joan Jett, from her early years as the founder of The Runaways and first meeting collaborator Kenny Laguna in 1980 to her enduring presence in pop culture as a rock ‘n’ roll pioneer. LONG SYNOPSIS When a precocious 13 -year-old girl in a sleepy suburban town put a Sears electric guitar at the top of her Christmas list in 1971, no one could have predicted how the gift would change the course of history. Joan Jett wanted to make some noise. She wanted to start a band. An all -girl band. Never mind that the only viable path forward for aspiring female artists in the male-dominated music industry was as a singer -songwriter on an acoustic guitar. Jett wanted to plug in, and nothing was going to stop her. Bad Reputation chronicles the life of Joan Jett, from her early teenage years as founding member of The Runaways to her enduring presence over four decades later as a rock ‘n’ roll icon. Following the break- up of The Runaways, Jett met songwriting partner and producer Kenny Laguna, and formed Joan Jett & the Blackhearts. After being rejected by twenty three labels, Laguna and Jett formed Blackhearts Records, selling records out of the trunk of Kenny’s Cadillac. -

Revolution Girl Style: Punk Feminism, Then and Now First Year Seminar, LMU, Fall 2013: Culture, Art and Society Tuesdays and Thursdays, 3‐415 P.M

August 29, 2013, RGS Syllabus COURSE TITLE (FFYS 1000 – 64): Revolution Girl Style: Punk Feminism, Then and Now First Year Seminar, LMU, Fall 2013: Culture, Art and Society Tuesdays and Thursdays, 3‐415 p.m. St. Rober’s Hall 357 INSTRUCTOR: Evelyn McDonnell Room 3866, University Hall 310-258-2662 Office hours: T, Th 12:45 – 2:45 p.m. [email protected] WRITING INSTUCTOR: Liz Goldhammer University Hall 3225 Office Hours: Tuesday, 4:30‐6:30, or by appointment Course Description: In the early 1990s, a group of young women from both coasts of the United States began calling for, as the punk band Bikini Kill put it, Revolution Girl Style Now. Twenty years later, their cry was picked up by a performance‐art collective in the Soviet Union who, in homage to their Riot Grrrl predecessors, called themselves Pussy Riot. Revolution Girl Style will explore the flash point in feminist and musical history that’s generally known as Riot Grrrl. By analyzing the music, art, and writings of such acts and artists as Bikini Kill, Mecca Normal, Bratmobile, the Runaways, Tribe 8, Fifth Column, Guerrilla Girls, the Slits, X‐Ray Spex, Sleater‐ Kinney, and Pussy Riot, the course will examine how music can be used for political action, and visa versa. Students will explore the activist and artistic history and context of Riot Grrrl and its global resuscitation in 2012. By crafting their own print or multimedia fanzines, students will learn how to express themselves politically and creatively. Musicians, artists, scholars, and experts will speak about their own involvement with RGS.