Representing Riot Grrrl David Buckingham This Essay Is Part of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death of Postfeminism : Oprah and the Riot Grrrls Talk Back By

The death of postfeminism : Oprah and the Riot Grrrls talk back by Cathy Sue Copenhagen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Montana State University © Copyright by Cathy Sue Copenhagen (2002) Abstract: This paper addresses the ways feminism operates in two female literary communities: the televised Oprah Winfrey talk show and book club and the Riot Grrrl zine movement. Both communities are analyzed as ideological responses of women and girls to consumerism, media conglomeration, mainstream appropriation of movements, and postmodern "postfeminist" cultural fragmentation. The far-reaching "Oprah" effect on modem publishing is critiqued, as well as the controversies and contradictions of the effect. Oprah is analyzed as a divided text operating in a late capitalist culture with third wave feminist tactics. The Riot Grrrl movement is discussed as the potential beginning of a fourth wave of feminism. The Grrrls redefine feminism and femininity in their music and writings in zines. The two sites are important to study as they are mainly populated by under represented segments of "postfeminist" society: middle aged women and young girls. THE DEATH OF "POSTFEMINISM": OPRAH AND THE RIOT GRRRLS TALK BACK by Cathy Sue Copenhagen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, MT May 2002 ii , ^ 04 APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Cathy Sue Copenhagen This thesis has been read by each member of a thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English Usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the College of Graduate Studies. -

Download PDF > Riot Grrrl \\ 3Y8OTSVISUJF

LWSRQOQGSW3L / Book ~ Riot grrrl Riot grrrl Filesize: 8.18 MB Reviews Unquestionably, this is actually the very best work by any article writer. It usually does not price a lot of. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Augustine Pfannerstill) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GOKP10TMWQNH / Kindle ~ Riot grrrl RIOT GRRRL To download Riot grrrl PDF, make sure you refer to the button under and download the document or gain access to other information which might be related to RIOT GRRRL book. Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 54. Chapters: Kill Rock Stars, Sleater-Kinney, Tobi Vail, Kathleen Hanna, Lucid Nation, Jessicka, Carrie Brownstein, Kids Love Lies, G. B. Jones, Sharon Cheslow, The Shondes, Jack O Jill, Not Bad for a Girl, Phranc, Bratmobile, Fih Column, Caroline Azar, Bikini Kill, Times Square, Jen Smith, Nomy Lamm, Huggy Bear, Karen Finley, Bidisha, Kaia Wilson, Emily's Sassy Lime, Mambo Taxi, The Yo-Yo Gang, Ladyfest, Bangs, Shopliing, Mecca Normal, Voodoo Queens, Sister George, Heavens to Betsy, Donna Dresch, Allison Wolfe, Billy Karren, Kathi Wilcox, Tattle Tale, Sta-Prest, All Women Are Bitches, Excuse 17, Pink Champagne, Rise Above: The Tribe 8 Documentary, Juliana Luecking, Lungleg, Rizzo, Tammy Rae Carland, The Frumpies, Lisa Rose Apramian, List of Riot Grrl bands, 36-C, Girl Germs, Cold Cold Hearts, Frightwig, Yer So Sweet, Direction, Viva Knievel. Excerpt: Riot grrrl was an underground feminist punk movement based in Washington, DC, Olympia, Washington, Portland, Oregon, and the greater Pacific Northwest which existed in the early to mid-1990s, and it is oen associated with third-wave feminism (it is sometimes seen as its starting point). -

Susan J. Douglas, Enlightened Sexism: the Seductive Message That Feminism's Work Is Done, New York: Times Books, 2010, 368 Pp, $26.00 (Hardcover).1

International Journal of Communication 5 (2011), Book Review 639–643 1932–8036/2011BKR0639 Susan J. Douglas, Enlightened Sexism: The Seductive Message that Feminism's Work is Done, New York: Times Books, 2010, 368 pp, $26.00 (hardcover).1 Reviewed by Umayyah Cable University of Southern California With biting wit, Susan Douglas’ Enlightened Sexism: The Seductive Message that Feminism's Work is Done sets out to historicize the ever growing divide between the image and the reality of women in the United States. Refusing to fall for the trope of "post-feminism," Douglas is quick to point out that the current state of women's affairs is not reflective of the supposed successful completion of feminism, but is rather an indication of the insidious development of a cultural practice coined as "enlightened sexism." Defined as "feminist in its outward appearance . but sexist in its intent," enlightened sexism takes shape through carefully crafted representations of women that are "dedicated to the undoing of feminism" (p. 10). Douglas’ refusal of the conceptualization of this phenomenon as "post-feminism" stems from an astute observation that the current miserable state of women's affairs in the United States is not to be blamed on feminism (as the peddlers of enlightened sexism would have you think), but on "good, old-fashioned, grade-A sexism that reinforces good, old-fashioned, grade-A patriarchy" (p. 10). Aside from tracing the genealogy of enlightened sexism, this book emphasizes the sociopolitical consequences that are concealed beneath such a mentality, such as the systematic disenfranchisement of poor women and women of color under the so-called liberatory system of consumer capitalism, all while contradictory representations of women are disseminated as "proof" that the liberation of women has been achieved. -

Exploring “Girl Power”: Gender, Literacy and the Textual Practices of Young Women Attending an Elite School

English Teaching: Practice and Critique September, 2007, Volume 6, Number 2 http://education.waikato.ac.nz/research/files/etpc/2007v6n2art5 pp. 72-88 Exploring “girl power”: Gender, literacy and the textual practices of young women attending an elite school CLAIRE CHARLES Faculty of Education, Monash University ABSTRACT: Popular discourses concerning the relationship between gender and academic literacies have suggested that boys are lacking in particular, school-based literacy competencies compared with girls. Such discourses construct “gender” according to a binary framework and they obscure the way in which literacy and textual practices operate as a site in which gendered identities are constituted and negotiated by young people in multiple sites including schooling, which academic inquiry has often emphasized. In this paper I consider the school-based textual practices of young women attending an elite school, in order to explore how these practices construct “femininities”. Feminist education researchers have shown how young women negotiate discourses of feminine passivity and heterosexuality through their reading and writing practices. Yet discourses of girlhood and femininity have undergone important transformations in times of ‘girl power’ in which young women are increasingly constructed as successful, autonomous and sexually agentic. Thus young women’s reading and writing practices may well operate as a space in which new discourses around girlhood and femininity are constituted. Throughout the paper, I utilize the notion of “performativity”, understood through the work of Judith Butler, to show how textual practices variously inscribe and negotiate discourses of gender. Thus the importance of textual work in inscribing and challenging notions of gender is asserted. -

January/February 2014 Vol

The Gainesville Iguana January/February 2014 Vol. 28, Issue 1/2 CMC SpringBoard fundraiser March 21 by Joe Courter The date for the Civic Media Center’s annual SpringBoard fundraiser is Friday evening, March 21. There will be a new location this year after last year’s venture at Prairie Creek Lodge, and that is in the heart of Down- town Gainesville at the Wooly, 20 N. Main St., a new event venue in what is the old Woolworth building next to and run by The Top restaurant. There will be food from various area restaurants, a si- lent auction and raffle items, and awards. The speaker this year is an old friend of McDonald’s workers and allies strike on July 31, 2013 in Chicago. Photo by Steve Rhodes. the CMC, David Barsamian, the founder and main man with Alternative Radio, who said he is “honored to follow in No- 2013 in review: Aiming higher, am’s footsteps.” labor tries new angles and alliances That is fitting because Alternative Ra- by Jenny Brown ment that jobs that once paid the bills, dio has made a special effort to archive from bank teller to university instructor, Noam Chomsky talks since its founding This article originally appeared in the now require food stamps and Medicaid to in 1989. David’s radio show was a staple January 2014 issue of LaborNotes. You supplement the wages of those who work See SPRINGBOARD, p. 2 can read the online version, complete with informative links and resources, at www. every day. labornotes.org/2013/12/2013-review- California Walmart worker Anthony INSIDE .. -

Cashing in on “Girl Power”: the Commodification of Postfeminist Ideals in Advertising

CASHING IN ON “GIRL POWER”: THE COMMODIFICATION OF POSTFEMINIST IDEALS IN ADVERTISING _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by MARY JANE ROGERS Dr. Cristina Mislán, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2017 © Copyright by Mary Jane Allison Rogers 2017 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled CASHING IN ON “GIRL POWER”: THE COMMODIFICATION OF POSTFEMINIST IDEALS IN ADVERTISING presented by Mary Jane Rogers, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Cristina Mislán Professor Cynthia Frisby Professor Amanda Hinnant Professor Mary Jo Neitz CASHING IN ON “GIRL POWER” ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My utmost gratitude goes to my advisor, Dr. Cristina Mislán, for supporting me throughout this process. She honed my interest in critically studying gender issues in the media, and her guidance, honesty and encouragement are the reasons I was able to develop the conclusions presented in this paper. I would also like to thank Dr. Amanda Hinnant, Dr. Cynthia Frisby, and Dr. Mary Jo Neitz for their immensely helpful suggestions before and during the research process of this study. Their enthusiasm and guidance was incredibly meaningful, especially during the developmental stages of my research. Additionally, I would like to thank my friends and family for their ongoing support. Special mention needs to be made of Mallory, my cheerleader and motivator from the first day of graduate school, and my Dad and Mom, who have been there since the beginning. -

The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing Academic Programs and Advising 2020 The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot Adam Clark Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/studentawards Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Adam, "The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot" (2020). Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing. 16. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/studentawards/16 This Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Programs and Advising at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adam Clark Victoria Malawey, Gender & Music The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot “We’re gonna take over the punk scene for feminists” -Kathleen Hanna Although they share feminist ideals, the Russian art collective Pussy Riot distinguishes themselves from the U.S.-based Riot Grrrl Movement, as exemplified by the band Bikini Kill, because of their location-specific protest work in Moscow. Understanding how Pussy Riot is both similar to and different from Riot Grrrl is important for contextualizing the way we think about diverse, transnational feminisms so that we may develop more inclusive and nuanced ways in conceptualizing these feminisms in the future. While Pussy Riot shares similar ideals championed by Bikini Kill in the Riot Grrrl movement, they have temporal and location-specific activisms and each group has their own ways of protesting injustices against women and achieving their unique goals. -

Feminism, Inc.: Coming of Age in Girl Power Media Culture Emilie Zaslow 205 Pages, 2009, $26.00 USD (Paper) Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY, United States

Intersect, Vol 6, No 1 (2013) Feminism, Inc.: Coming of Age In Girl Power Media Culture Emilie Zaslow 205 pages, 2009, $26.00 USD (paper) Palgrave Macmillan, New York, NY, United States. Reviewed by Nathaniel Williams, Stanford University Most millennials remember the first time they heard a song by the Spice Girls, or fell in love with television shows like Buffy or Gilmore Girls, or even when they bought their first poster of a celebrity like Jennifer Lopez. These (and many other) cultural works define a generation of young Americans. However, in addition to the identity achieved through these cultural artifacts, these phenomena actually define much more—they are artifacts of girl power media that signify something much larger for the idea of what it is to be a young woman today. Emilie Zaslow presents a strong case for this understanding of seemingly innocuous media and cultural trends—this media genre is actually a carefully repackaged consumer good that obscures the processes of identity formation and future considerations for young women across the western world. Zaslow begins appropriately by defining the phrase girl power media, as it is the foundation from which the rest of the argument is built. According to Feminism, Inc., girl power media is epitomized by “crossings between girlishness and female empowerment”—a spectrum where girl power media is a midpoint between traditional femininity and powerful feminist agency (2). Furthermore, Zaslow insists that girl power media acts as a euphemism for what once was considered feminism, a euphemism pioneered by cultural heroes like the Spice Girls. She argues that girl power media has elements of both capitalistic strategy and empowerment through hyperidentity. -

Masculinity in Emo Music a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts and Social Science in Candi

CARLETON UNIVERSITY FLUID BODIES: MASCULINITY IN EMO MUSIC A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCE IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY RYAN MACK OTTAWA, ONTARIO MAY 2014 ABSTRACT Emo is a genre of music that typically involves male performers, which evolved out of the punk and hardcore movements in Washington DC during the mid-80s. Scholarly literature on emo has explored its cultural and social contexts in relation to the “crisis” of masculinity—the challenging of the legitimacy of patriarchy through “alternative” forms of masculinity. This thesis builds upon this pioneering work but departs from its perpetuation of strict masculine binaries by conflating hegemonic and subordinate/alternative masculinities into a single subject position, which I call synergistic masculinity. In doing so, I use emo to explicate this vis-à-vis an intertextual analysis that explores the dominant themes in 1) lyrics; 2) the sites of vocal production (head, throat, chest) in conjunction with pitch and timbre; 3) the extensional and intensional intervallic relationships between notes and chords, and the use of dynamics in the musical syntax; 4) the use of public and private spaces, as well as the performative masculine body in music video. I posit that masculine emo performers dissolve these hierarchically organized masculinities, which allows for a deeper musical meaning and the extramusical signification of masculinity. Keywords: emo, synergistic masculinity, performativity, music video, masculinities, lyrics, vocal production, musical syntax, dynamics. ABSTRAIT Emo est un genre musical qui implique typiquement des musiciens de sexe masculine et qui est issu de movement punk et hardcore originaire de Washington DC durant les années 80. -

Disidentification and Evolution Within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2012 (R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College Recommended Citation Estenson, Lilly, "(R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism" (2012). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 94. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/94 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (R)EVOLUTION GRRRL STYLE NOW: DISIDENTIFICATION AND EVOLUTION WITHIN RIOT GRRRL FEMINISM by LILLY ESTENSON SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR CHRIS GUZAITIS PROFESSOR KIMBERLY DRAKE April 20, 2012 Estenson 1 Table of Contents Introduction ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Chapter 1: Contextualizing Riot Grrrl Feminism ---------------------------------------- 20 Chapter 2: Feminist Praxis in the Original Riot Grrrl Movement (1990-96) ------- 48 Chapter 3: Subcultural Disidentification and Contemporary Riot Grrrl Praxis --- 72 Conclusion ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 97 Works Cited ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

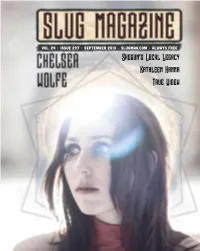

Shogun's Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow

Vol. 24 • Issue 297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com • Always Free Shogun’s Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow slugmag.com 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround slugmag.com 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 24 • Issue #297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com facebook.com/SLUG.Mag @SLUGMag @SLUGMag youtube.com/user/SLUGMagazine Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Manager: Editor: Angela H. Brown Karamea Puriri Managing Editor: Esther Meroño Marketing Team: Ischa B., Sabrina Costello, Editorial Assistant: Alexander Ortega Kristina Sandi, Brooklyn Ottens, Angella Luci- Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan sano, Nicole Roccanova, Raffi Shahinian, Vic- Digital Content Coordinator: Cody Kirkland toria Loveless, Zac Freeman, Cassie Anderson, Copy Editing Team: Esther Meroño, Alexan- Cassie Loveless, Shley Kinser, Matt Brunk, Robin der Ortega, Mary E. Duncan, Cody Kirkland, Sessions, Carl Acheson, Chandler Hunt Johnathan Ford, Alex Cragun, Rachel Miller, Ka- Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer tie Bald, Liz Phillips, Allison Shephard, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Shawn Soward Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Tony Cover Designer: Joshua Joye Bassett, Nancy Burkhart, Adam Okeefe, Ryan Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Worwood, John Ford, Matt Pothier, Phil Cannon, Design Team: Eleanor Scholz, BJ Viehl, Lenny Tim Kronenberg, Justin Nelson-Carruth, Xkot Riccardi, Chad Pinckney, Mason Rodrickc Toxsik, Nancy Perkins Ad Designers: Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Christian Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Eric Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, Mariah Sapp, Brad Barker, Paden Bischoff, Maggie Mann-Mellus, James Orme, Lance Saunders, Zukowski, Thy Doan, KJ Jackett, Nicholas Dowd, Bryer Wharton, Peter Fryer, James Bennett, Ricky Nick Ketterer Vigil, Gavin Hoffman, Esther Meroño, Rebecca Website Design: Kate Colgan Vernon, Jimmy Martin, Ben Trentelman, Princess Office Interns: Carl Acheson, Robin Sessions, Kennedy, Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Cody Hudson, Alex Cragun, Chandler Hunt Shawn Mayer, Dean O. -

Words and Guitar

# 2021/24 dschungel https://jungle.world/artikel/2021/24/words-and-guitar Ein Rückblick auf die Diskographie von Sleater-Kinney Words and Guitar Von Dierk Saathoff Vojin Saša Vukadinović Zehn Alben haben Sleater-Kinney in den 27 Jahren seit ihrer Gründung aufgenommen, von denen das zehnte, »Path of Wellness«, kürzlich erschienen ist. Ein Rückblick auf die Diskographie der wohl besten Band der Welt. »Sleater-Kinney« (LP: Villa Villakula, CD: Chainsaw Records, 1995) 1995 spielten die beiden Gitarristinnen Corin Tucker und Carrie Brownstein erst seit einem Jahr unter dem Namen Sleater-Kinney, waren nach Misty Farrell und Stephen O’Neil (The Cannanes) aber bereits bei der dritten Besetzung am Schlagzeug angelangt, der schottisch-australischen Indie-Musikerin Lora MacFarlane. Nach einer frechen Single und Compilation-Tracks auf Tinuviel Sampsons feministischem Label Villa Villakula erschien dort das Vinyl vom Debütalbum, die CD-Version aber auf Donna Dreschs Queercore-Label Chainsaw. Selten klang Angst durchdringender als auf diesem derben wie dunklen Erstlingswerk, das mit zehn Liedern in weniger als 23 Minuten aufwartet. Corin Tucker kreischt sich die Seele aus dem Leib und Carrie Brownsteins Schreien auf »The Last Song« stellt mit Leichtigkeit ganze Karrieren mediokrer männlicher Hardcore-Bands in den Schatten. Mit Sicherheit nicht nur das unterschätzteste Album der Bandgeschichte, sondern des Punk in den neunziger Jahren überhaupt. »Call the Doctor« (Chainsaw Records, 1996) Album Nummer zwei zeigte eine enorme musikalische Weiterentwicklung. »Call the Doctor« ist das streckenweise intelligenteste Album von Sleater-Kinney, das sich einerseits vor der avancierten Musikszene im Nordwesten der USA verneigte, in der die Band entstanden war (Olympia, Washington), zugleich aber äußerst eigenständig vorwärtspreschte und bei allem Zorn auf die Ausprägungen misogyner Kultur Anflüge von Zärtlichkeit nicht scheute: Selten wurde Unsicherheit so ehrlich vorgetragen wie auf »Heart Attack«.