The Rhetoric of Riot Grrrl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

Download PDF > Riot Grrrl \\ 3Y8OTSVISUJF

LWSRQOQGSW3L / Book ~ Riot grrrl Riot grrrl Filesize: 8.18 MB Reviews Unquestionably, this is actually the very best work by any article writer. It usually does not price a lot of. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Augustine Pfannerstill) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GOKP10TMWQNH / Kindle ~ Riot grrrl RIOT GRRRL To download Riot grrrl PDF, make sure you refer to the button under and download the document or gain access to other information which might be related to RIOT GRRRL book. Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 54. Chapters: Kill Rock Stars, Sleater-Kinney, Tobi Vail, Kathleen Hanna, Lucid Nation, Jessicka, Carrie Brownstein, Kids Love Lies, G. B. Jones, Sharon Cheslow, The Shondes, Jack O Jill, Not Bad for a Girl, Phranc, Bratmobile, Fih Column, Caroline Azar, Bikini Kill, Times Square, Jen Smith, Nomy Lamm, Huggy Bear, Karen Finley, Bidisha, Kaia Wilson, Emily's Sassy Lime, Mambo Taxi, The Yo-Yo Gang, Ladyfest, Bangs, Shopliing, Mecca Normal, Voodoo Queens, Sister George, Heavens to Betsy, Donna Dresch, Allison Wolfe, Billy Karren, Kathi Wilcox, Tattle Tale, Sta-Prest, All Women Are Bitches, Excuse 17, Pink Champagne, Rise Above: The Tribe 8 Documentary, Juliana Luecking, Lungleg, Rizzo, Tammy Rae Carland, The Frumpies, Lisa Rose Apramian, List of Riot Grrl bands, 36-C, Girl Germs, Cold Cold Hearts, Frightwig, Yer So Sweet, Direction, Viva Knievel. Excerpt: Riot grrrl was an underground feminist punk movement based in Washington, DC, Olympia, Washington, Portland, Oregon, and the greater Pacific Northwest which existed in the early to mid-1990s, and it is oen associated with third-wave feminism (it is sometimes seen as its starting point). -

Disidentification and Evolution Within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2012 (R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College Recommended Citation Estenson, Lilly, "(R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism" (2012). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 94. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/94 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (R)EVOLUTION GRRRL STYLE NOW: DISIDENTIFICATION AND EVOLUTION WITHIN RIOT GRRRL FEMINISM by LILLY ESTENSON SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR CHRIS GUZAITIS PROFESSOR KIMBERLY DRAKE April 20, 2012 Estenson 1 Table of Contents Introduction ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Chapter 1: Contextualizing Riot Grrrl Feminism ---------------------------------------- 20 Chapter 2: Feminist Praxis in the Original Riot Grrrl Movement (1990-96) ------- 48 Chapter 3: Subcultural Disidentification and Contemporary Riot Grrrl Praxis --- 72 Conclusion ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 97 Works Cited ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

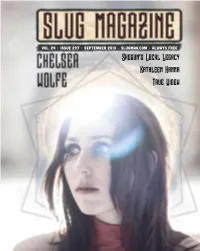

Shogun's Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow

Vol. 24 • Issue 297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com • Always Free Shogun’s Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow slugmag.com 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround slugmag.com 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 24 • Issue #297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com facebook.com/SLUG.Mag @SLUGMag @SLUGMag youtube.com/user/SLUGMagazine Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Manager: Editor: Angela H. Brown Karamea Puriri Managing Editor: Esther Meroño Marketing Team: Ischa B., Sabrina Costello, Editorial Assistant: Alexander Ortega Kristina Sandi, Brooklyn Ottens, Angella Luci- Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan sano, Nicole Roccanova, Raffi Shahinian, Vic- Digital Content Coordinator: Cody Kirkland toria Loveless, Zac Freeman, Cassie Anderson, Copy Editing Team: Esther Meroño, Alexan- Cassie Loveless, Shley Kinser, Matt Brunk, Robin der Ortega, Mary E. Duncan, Cody Kirkland, Sessions, Carl Acheson, Chandler Hunt Johnathan Ford, Alex Cragun, Rachel Miller, Ka- Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer tie Bald, Liz Phillips, Allison Shephard, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Shawn Soward Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Tony Cover Designer: Joshua Joye Bassett, Nancy Burkhart, Adam Okeefe, Ryan Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Worwood, John Ford, Matt Pothier, Phil Cannon, Design Team: Eleanor Scholz, BJ Viehl, Lenny Tim Kronenberg, Justin Nelson-Carruth, Xkot Riccardi, Chad Pinckney, Mason Rodrickc Toxsik, Nancy Perkins Ad Designers: Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Christian Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Eric Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, Mariah Sapp, Brad Barker, Paden Bischoff, Maggie Mann-Mellus, James Orme, Lance Saunders, Zukowski, Thy Doan, KJ Jackett, Nicholas Dowd, Bryer Wharton, Peter Fryer, James Bennett, Ricky Nick Ketterer Vigil, Gavin Hoffman, Esther Meroño, Rebecca Website Design: Kate Colgan Vernon, Jimmy Martin, Ben Trentelman, Princess Office Interns: Carl Acheson, Robin Sessions, Kennedy, Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Cody Hudson, Alex Cragun, Chandler Hunt Shawn Mayer, Dean O. -

Relatório Parcial De Pesquisa De Iniciação Científica Mídia E Polícia Na (Des) Construção Do Movimento Punk Paulistano

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO PUC-SP Relatório Parcial de Pesquisa de Iniciação Científica Mídia e polícia na (des) construção do movimento punk paulistano Bolsista Flávia Lucchesi de Carvalho Leite Orientador Edson Passetti SÃO PAULO 2012 1 SUMÀRIO 1.Relatório das Atividades................................................................................................3 1.1.Atividades desenvolvidas................................................................................3 2.Relatório Científico........................................................................................................7 2.1.Resultados preliminares...................................................................................7 2.1.1.Rock, punk, mulheres e espaço..........................................................8 2.1.2. The herstory e as meninas da cena punk........................................14 2.1.3.Mídia e riot grrrl.............................................................................28 2.2. Cuidado de si e cuidado do outro..................................................................37 2.2.1. A união das mulheres…………………………………….............38 2.2.2. Auto-ajuda…………………………….........................................40 2.3.Sexo...............................................................................................................42 2.4 Resignificações e demolições........................................................................46 2.4.1. A novo linguagem slut...................................................................47 -

For the Love of It?: Zine Writing and the Study Of

FOR THE LOVE OF IT?: ZINE WRITING AND THE STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY AMATEUR WORK A Dissertation by EMILY SARA HOEFLINGER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Mary Ann O’Farrell Committee Members, Sally Robinson Giovanna Del Negro Joan Wolf Head of Department, Maura Ives May 2016 Major Subject: English Copyright 2016 Emily Sara Hoeflinger ABSTRACT In this project, I am examining zines in relation to the question of contemporary amateurism. With the onset of Web 2.0 came a space for new forms of amateur work, but this new work hasn’t been addressed as “amateur,” which has revealed a problem between what theorists know the amateur to be and what has been embraced by mainstream culture. This oversimplification of the definition of amateurism seems to threaten the integrity of amateur work in general. I analyze the concepts “transparency” and “distance” and show that both highlight the need for preserving the amateur. I confront the notion of “for the love it” by interrogating the boundaries that zine writers have established and the misperception that zine work somehow remains on the fringe of capitalist culture. Moreover, I identify the Pro Am (professional amateur) as the most significant contemporary amateur figure because it directly challenges not only what it means to be professional, but also what it means to be amateur. By examining perzines and glossies, I argue that while “for the love of it” has been downplayed or even ignored, internal rewards are still an important factor in what makes an act amateur and that external rewards don’t always have to be monetary. -

'Race Riot' Within and Without 'The Grrrl One'; Ethnoracial Grrrl Zines

The ‘Race Riot’ Within and Without ‘The Grrrl One’; Ethnoracial Grrrl Zines’ Tactical Construction of Space by Addie Shrodes A thesis presented for the B. A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2012 © March 19, 2012 Addie Cherice Shrodes Acknowledgements I wrote this thesis because of the help of many insightful and inspiring people and professors I have had the pleasure of working with during the past three years. To begin, I am immensely indebted to my thesis adviser, Prof. Gillian White, firstly for her belief in my somewhat-strange project and her continuous encouragement throughout the process of research and writing. My thesis has benefitted enormously from her insightful ideas and analysis of language, poetry and gender, among countless other topics. I also thank Prof. White for her patient and persistent work in reading every page I produced. I am very grateful to Prof. Sara Blair for inspiring and encouraging my interest in literature from my first Introduction to Literature class through my exploration of countercultural productions and theories of space. As my first English professor at Michigan and continual consultant, Prof. Blair suggested that I apply to the Honors program three years ago, and I began English Honors and wrote this particular thesis in a large part because of her. I owe a great deal to Prof. Jennifer Wenzel’s careful and helpful critique of my thesis drafts. I also thank her for her encouragement and humor when the thesis cohort weathered its most chilling deadlines. I am thankful to Prof. Lucy Hartley, Prof. -

Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: the Riot Grrrl Revolution As a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance Summit J

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2016 Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: The Riot Grrrl Revolution as a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance Summit J. Starr The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Starr, Summit J., "Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: The Riot Grrrl Revolution as a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance" (2016). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 7022. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/7022 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2016 Summit J. Starr The College of Wooster Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: The Riot Grrrl Revolution as a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance by Summit J. Starr Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Senior Independent Study Requirement Theatre and Dance 451 - 452 Advised by Jimmy A. Noriega Department of Theatre & Dance March 28th, 2016 1 | Starr Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………….………………3 Acknowledgements……………………………….………….……….……………..4 Introduction and Literature Review …………...…………………………….…….5 Chapter One: Technique and Aesthetics……...……………………….…………..18 Chapter Two: Devising Concept……………………………………….…………..31 Chapter Three: Reflection…………………………………………………………...46 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………63 Appendix A…………………………………………………………………………..65 Bibliography and Works Cited ……………………………………………………..97 2 | Starr Abstract My Independent Study focuses on the technique and aesthetic of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, and how those elements effectively continued the 90s underground punk scene. -

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33 ________________________________________________________________________ 0:00:00 Davis: Today is June 15th, 2017. My name is John Davis. I’m the performing arts metadata archivist at the University of Maryland, speaking to Allison Wolfe. Wolfe: Are you sure it’s the 15th? Davis: Isn’t it? Yes, confirmed. Wolfe: What!? Davis: June 15th… Wolfe: OK. Davis: 2017. Wolfe: Here I am… Davis: Your plans for the rest of the day might have changed. Wolfe: [laugh] Davis: I’m doing research on fanzines, particularly D.C. fanzines. When I think of you and your connection to fanzines, I think of Girl Germs, which as far as I understand, you worked on before you moved to D.C. Is that correct? Wolfe: Yeah. I think the way I started doing fanzines was when I was living in Oregon—in Eugene, Oregon—that’s where I went to undergrad, at least for the first two years. So I went off there like 1989-’90. And I was there also the year ’90-’91. Something like that. For two years. And I met Molly Neuman in the dorms. She was my neighbor. And we later formed the band Bratmobile. But before we really had a band going, we actually started doing a fanzine. And even though I think we named the band Bratmobile as one of our earliest things, it just was a band in theory for a long time first. But we wanted to start being expressive about our opinions and having more of a voice for girls in music, or women in music, for ourselves, but also just for things that we were into. -

The Appropriation and Packaging of Riot Grrrl Politics by Mainstream Female Musicians

Popular Music and Society, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2003 “A Little Too Ironic”: The Appropriation and Packaging of Riot Grrrl Politics by Mainstream Female Musicians Kristen Schilt “RIOT GIRL IS: BECAUSE I believe with my wholeheartmindbody that girls constitute a revolutionary soul force that can, and will, change the world for real” (“Riot Grrrl Is” 44) “Girl power!” (Spice Girls) Introduction Female rock musicians have had difficulty making it in the predominantly white male rock world. Joanne Gottlieb and Gayle Wald note that women’s participation in rock music usually consists of bolstering male performance, in the roles of groupie, girlfriend, or back-up singer (257). Even in punk rock, women are often treated as a novelty by the music press and cultural critics. Male bands such as the Sex Pistols and the Damned achieve rock notoriety while their female counterparts, like the Slits and the Raincoats, sink into obscurity. However, 1995 saw an explosion in the music press about a new group of female musicians: the angry women. Hailed in popular magazines for blending feminism and rock music, Alanis Morissette topped the charts in 1995. Affectionately named the “screech queen” by Newsweek, Morissette combined angry, sexually graphic lyrics with catchy pop music (Chang 79). She was quickly followed by Tracy Bonham, Meredith Brooks, and Fiona Apple. Though they differed in musical style, this group of musicians embodied what it meant to be a woman expressing anger through rock music, according to the music press. Popular music magazines argued that musicians like Morissette were creating a whole new genre for female performers, one that allowed them to assert their ideas about feminism and sexual- ity. -

Adyslipper Music by Women Table of Contents

.....••_•____________•. • adyslipper Music by Women Table of Contents Ordering Information 2 Arabic * Middle Eastern 51 Order Blank 3 Jewish 52 About Ladyslipper 4 Alternative 53 Donor Discount Club * Musical Month Club 5 Rock * Pop 56 Readers' Comments 6 Folk * Traditional 58 Mailing List Info * Be A Slipper Supporter! 7 Country 65 Holiday 8 R&B * Rap * Dance 67 Calendars * Cards 11 Gospel 67 Classical 12 Jazz 68 Drumming * Percussion 14 Blues 69 Women's Spirituality * New Age 15 Spoken 70 Native American 26 Babyslipper Catalog 71 Women's Music * Feminist Music 27 "Mehn's Music" 73 Comedy 38 Videos 77 African Heritage 39 T-Shirts * Grab-Bags 82 Celtic * British Isles 41 Songbooks * Sheet Music 83 European 46 Books * Posters 84 Latin American . 47 Gift Order Blank * Gift Certificates 85 African 49 Free Gifts * Ladyslipper's Top 40 86 Asian * Pacific 50 Artist Index 87 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 (Mon-Fri 9-8, Sat'11-5) Ordering Information INFORMATION: 919-683-1570 (same as above) FAX: 919-682-5601 (24 hours'7 days a week) PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK-ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are FORMAT: Each description states which formats are don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and temporarily out of stock on a title, we will automati available. LP = record, CS = cassette, CD = com schools). Make check or money order payable to cally back-order it unless you include alternatives pact disc. Some recordings are available only on LP Ladyslipper, Inc. -

“We ARE the Revolution”: Riot Grrrl Press, Girl Empowerment, and DIY Self-Publishing

Women's Studies An inter-disciplinary journal ISSN: 0049-7878 (Print) 1547-7045 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gwst20 “We ARE the Revolution”: Riot Grrrl Press, Girl Empowerment, and DIY Self-Publishing KEVIN DUNN & MAY SUMMER FARNSWORTH To cite this article: KEVIN DUNN & MAY SUMMER FARNSWORTH (2012) “We ARE the Revolution”: Riot Grrrl Press, Girl Empowerment, and DIY Self-Publishing, Women's Studies, 41:2, 136-157, DOI: 10.1080/00497878.2012.636334 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00497878.2012.636334 Published online: 11 Jan 2012. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1979 View related articles Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gwst20 Download by: [University of Warwick] Date: 25 October 2017, At: 11:38 Women’s Studies, 41:136–157, 2012 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0049-7878 print / 1547-7045 online DOI: 10.1080/00497878.2012.636334 “WE ARE THE REVOLUTION”: RIOT GRRRL PRESS, GIRL EMPOWERMENT, AND DIY SELF-PUBLISHING KEVIN DUNN and MAY SUMMER FARNSWORTH Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Geneva Punk rock emerged in the late 20th century as a major disruptive force within both the established music scene and the larger capitalist societies of the industrial West. Punk was generally characterized by its anti-status quo disposition, a pronounced do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos, and a desire for disalienation (resis- tance to the multiple forms of alienation in modern society). These three elements provided actors with tools for political inter- ventions and actions.