For the Love of It?: Zine Writing and the Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Progress 1990-1991 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1990-1991 Eastern Progress 1-17-1991 Eastern Progress - 17 Jan 1991 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1990-91 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 17 Jan 1991" (1991). Eastern Progress 1990-1991. Paper 16. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1990-91/16 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1990-1991 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Activities Weekend weather Moo-ving art All together now Pressing on Friday: Dry afternoon, night low near 20. New faculty art exhibit E Pluribus Unum Colonels push Saturday and Sunday: features ceramics kicks off Monday to 2-1 in OVC Clear and dry, high of and photographs Page B-2 Page B-4 Page B-6 40. Low near 20. THE EASTERN PROGRESS Vol. 69/No. 16 16 pages January 17,1991 Student publication ot Eastern Kentucky University, Richmond, Ky. 40475 © The Eastern Progress, 1991 Middle Eastern War Zone A moment of silence Syria- Persian Gult X Mediterranean Sea Source: Cable News Network Progress grmphic by TERRY SEBASTIAN Coalition forces launch offensive on Iraqi targets War won't affect university, Funderburk says By Mike Royer, Tom Marshall middle of hell." and Joe Castle Late last night CNN reported the mission Candlelight vigil unites was "a blowout" with no allied losses, ac- It happened. cording to reports from CNN quotinq a At 7 p.m. -

Podcasting Fandom”

Podcasts and Convergent Digital Media, pt. 2 “Podcasting Fandom” Paul Booth, College of Communication, DePaul University What does overtly “being a fan” reflect about the contemporary fan experience? What one person considers fannish behavior might not be considered fannish by others. Indeed, fandom is both personal (in that it is something experienced within the self) and public (in that no one will know you are a fan if you don’t display it in some way). In the convergent digital media era, fandom is profoundly mutable. From armchair fan to fan fiction author, from convention-goer to podcast-maker, “being a fan” can mean many things in many different corners of the web. Not only can one be a fan in the quiet of one’s own living room, but one can be a fan—a loud fan— online and with others in a podcast. With the increasingly rapid monetization of fandom throughout the media environment, however, I want to explore the various ways that podcasting fandom can problematize contemporary discourses of fan activity. How does podcasting change our notions of fandom? And how does fandom change our notions of podcasting? For the mainstream media industries, fandom does have a particular identity—one marked with a dollar sign. Fans are big business. Media corporations have harnessed fan work for advertising, have used fans to Tweet news, have enabled online contests to sell fans’ information on mailing lists, have developed platforms for fan interaction, and have made countless millions of dollars on advertising and page views. It is the era of “broadcast yourself” on YouTube and “what’s happening” on Twitter: And while social media platforms are useful for fans’ organization and connection, fans ultimately serve a commercial agenda for these platforms. -

A Double Détournement in the Classroom: HK Protest Online Game As Conceptual Art

A Double Détournement in the Classroom: HK Protest Online Game as Conceptual Art James Shea Department of Humanities and Creative Writing, Hong Kong Baptist University [email protected] Abstract law professor and co-director of the Center for Law and Intellectual Property at Texas A&M University School of This paper examines the role of digital détournement during Law: Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement in late 2014 through the prism of HK Protest Online Game, a conceptual art game made “They drafted the legislation so broadly that it in response to Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests. Created covers most of the activities the netizens have by an undergraduate Hong Kong student, this work invites a critical reflection on playability by questioning the relationship been doing…Just saying ‘we’re not going to between videogames, play, and “real time” violence. As an prosecute you’ doesn’t address the concerns of unplayable game, it reroutes the player to contemporaneous the netizens. Most people now interpret this as street demonstrations in Hong Kong, serving both as a something that targets their freedom of speech.” détournement of police aggression and of videogames that [4] commercialize violence. Reversing our expectation of games as playful and political action as non-playful, HKPOG presents its What are the implications for creating digital game as unreal and posits Hong Kong’s protests as sites of artwork, including art games, that “plays” with source play. The paper considers related digital artwork and the use of texts, such as digital détournement, if such forms are détournement during the Umbrella Movement, including umbrellas themselves and digitalized “derivative works” also restricted or prohibited in Hong Kong? The bills lacks a known as “secondary creation” (yihchi chongjok in Cantonese clear exemption for “fair use” or “user-generated and èrcì chuàngzuò in Mandarin; 二次創作). -

Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding Katharina M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding Katharina M. Freund University of Wollongong, [email protected] Recommended Citation Freund, Katharina M., "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3447 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] “Veni, Vidi, Vids!”: Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy From University of Wollongong by Katharina Freund (BA Hons) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications 2011 CERTIFICATION I, Katharina Freund, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Arts Faculty, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Katharina Freund 30 September, 2011 i ABSTRACT This thesis documents and analyses the contemporary community of (mostly) female fan video editors, known as vidders, through a triangulated, ethnographic study. It provides historical and contextual background for the development of the vidding community, and explores the role of agency among this specialised audience community. Utilising semiotic theory, it offers a theoretical language for understanding the structure and function of remix videos. -

The Hyper Sexual Hysteric: Decadent Aesthetics and the Intertextuality of Transgression in Nick Cave’S Salomé

The Hyper Sexual Hysteric: Decadent Aesthetics and the Intertextuality of Transgression in Nick Cave’s Salomé Gerrard Carter Département d'études du monde anglophone (DEMA) Aix-Marseille Université Schuman - 29 avenue R. Schuman - 13628 Aix-en-Provence, , France e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Salomé (1988), Nick Cave’s striking interpretation of the story of the Judean princess enhances and extends the aesthetic and textual analysis of Oscar Wilde’s 1891 French symbolist tragedy (Salomé), yet it is largely overlooked. As we examine the prior bricolage in the creation of such a hypertextual work, we initiate a captivating literary discourse between the intertextual practices and influences of biblical and fin-de-siècle literary texts. The Song of Songs, a biblical hypotext inverted by Wilde in the creation of the linguistic-poetic style he used in Salomé, had never previously been fully explored in such an overt manner. Wilde chose this particular book as the catalyst to indulge in the aesthetics of abjection. Subsequently, Cave’s enterprise is entwined in the Song’s mosaic, with even less reserve. Through a semiotic and transtextual analysis of Cave’s play, this paper employs Gérard Genette’s theory of transtextuality as it is delineated in Palimpsests (1982) to chart ways in which Cave’s Salomé is intertwined with not only Wilde but also the Song of Songs. This literary transformation demonstrates the potential and skill of the artist’s audacious postmodern rewriting of Wilde’s text. Keywords: Salomé, Nick Cave, Oscar Wilde, The Song of Songs, Aesthetics, Gérard Genette, Intertextuality, Transtextuality, Transgression, Puvis de Chavannes. -

For Fans by Fans: Early Science Fiction Fandom and the Fanzines

FOR FANS BY FANS: EARLY SCIENCE FICTION FANDOM AND THE FANZINES by Rachel Anne Johnson B.A., The University of West Florida, 2012 B.A., Auburn University, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Department of English and World Languages College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities The University of West Florida In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2015 © 2015 Rachel Anne Johnson The thesis of Rachel Anne Johnson is approved: ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Baulch, Ph.D., Committee Member Date ____________________________________________ _________________ David M. Earle, Ph.D., Committee Chair Date Accepted for the Department/Division: ____________________________________________ _________________ Gregory Tomso, Ph.D., Chair Date Accepted for the University: ____________________________________________ _________________ Richard S. Podemski, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School Date ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank Dr. David Earle for all of his help and guidance during this process. Without his feedback on countless revisions, this thesis would never have been possible. I would also like to thank Dr. David Baulch for his revisions and suggestions. His support helped keep the overwhelming process in perspective. Without the support of my family, I would never have been able to return to school. I thank you all for your unwavering assistance. Thank you for putting up with the stressful weeks when working near deadlines and thank you for understanding when delays -

Aligning the Ethos of Zines with Youth-Driven Philosophical Inquiry

Journal of Unschooling and Alternative Learning 2017 Vol. 11 Issue 22 DESIGNING A SPACE FOR THOUGHTUL VOICES: ALIGNING THE ETHOS OF ZINES WITH YOUTH-DRIVEN PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY By: Natalie M. FLETCHER Abstract This article strives to lay some necessary theoretical groundwork for justifying an alliance between zining and youth-driven “philosophical inquiry” (Lipman, 2004)—two important practices that operate outside the mainstream yet can shed light on conventional (mis)understandings of youth by illustrating innovative ways of designing space for young voices to emerge and thrive in their educational experiences and beyond. By highlighting the shared ethos between zining and philosophical inquiry as practices that foster meaning-making, this article aims to emphasize their common participatory, do-it-yourself, experimental, politicizing and transformative features, while noting the challenges involved in extending them to the context of childhood. Further, it illustrates how aligning zining and philosophical inquiry can contribute to a re-envisioning of children by portraying them as capable cultural producers and social historians of their own discourse communities. Lastly, it explores issues of adult authority, suggesting conditions that may help to authenticate the philosophical use of zines with youth. Keywords: Philosophy for Children, Zines, Philosophical Inquiry, Youth Agency Those without power also have the capability to create a culture— one that arises out of their way of understanding the world. —Stephen Duncombe, Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture An eight-year old philosopher is sitting in front of a small booklet wondering what she will write next. She’s deep in thought about the nature of imagination after a heated dialogue with other kids over the possibility of imagining something that does not exist. -

Alternate Universe Fan Videos and the Reinterpretation of the Media

Alternate Universe Fan Videos and the Reinterpretation of the Media Source Introduction According to the Francesca Coppa, American scholar and co-founder of the Organization for Transformative Works1, fan videos are “a form of grassroots filmmaking in which clips from television shows and movies are set to music.”2 Fan videos are commonly referred to as: fanvid, songvid, vid, AMV (for Anime Music Video); their process of creation is called vidding and their editors (fan)vidders. While the “media tradition” described above in Francesca Coppa‟s definition is a crucial part of the fan video production, many other fan videos are created for anime, especially Asian ones (AMV), for video games (some of them called Machinima), or even for other subjects, from band tributes to other types of remix. The vidding tradition – in its current “shape” – goes back to the era of the first VCR; but the very first fan videos may be traced back to the seventies in a slideshow format. When channel mixers and numerous machines available to a large group of consumers emerged, this fan activity easily became an expanding one amongst the fan communities, who were often interested in new technology, whatever era it is. Vidding has now become a digital process, thanks to the expansion of computer and related technical means, including at least semiprofessional editing software. It seems relevant to point out how rare it is that a vidder goes through editing training when they begin to create fan videos, or even become a professional editor later on. Of course, exceptions exist, but vidding generally remains a hobby. -

Video Game Détournement: Playing Across Media

Video Game Détournement: Playing Across Media Fanny Barnabé Liège Game Lab – University of Liège – FNRS Bât. A2 Litt. française (19è et 20è) Place Cockerill 3-5, 4000 Liège +32 4 3665503 [email protected] ABSTRACT Taking as a starting point the French concept of “artistic détournement” and its application in the context of video games, this paper aims to study creative remix practices that use video games as materials or as matrices to produce derivative works. Precisely, the research examines a diversified range of productions whose common feature is to be created from video games (mods, machinimas, let’s play videos…) in order to question the relationships between the notions of détournement and play. Where is the boundary between these two activities? How to define and categorize the various forms of détournements in the specific context of the video game culture? Can these remix practices that go beyond the frame of the game and extend themselves to other media be described as “playful”? By crossing rhetoric and theories of play, this paper will try to answer these questions. Keywords Remix, Détournement, Rhetoric, Play studies, Transmedia, Participatory culture INTRODUCTION: DEFINING DÉTOURNEMENT This paper aims to study the “détournements” of video games by players, that is to say: creative remix practices using video games as materials or as matrices to produce derivative works1. There are indeed a large number of fan productions whose common feature is to be created from video games (mods, machinimas, let’s play videos, fanfictions, etc.) and which often overflow the frame of the game software, extending themselves to other media (the video in the case of machinima or let's play; the text in the case of fanfictions; etc.). -

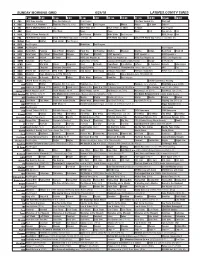

Sunday Morning Grid 6/24/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/24/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Special (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Program House House 1st Look Extra Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Japan vs Senegal. (N) FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Poland vs Colombia. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Belton Real Food Food 50 28 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Kid Stew Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La casa de mi padre (2008, Drama) Nosotr. Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Elenco Film Dal 2015 Al 2020

7 Minuti Regia: Michele Placido Cast: Cristiana Capotondi, Violante Placido, Ambra Angiolini, Ottavia Piccolo Genere: Drammatico Distributore: Koch Media Srl Uscita: 03 novembre 2016 7 Sconosciuti Al El Royale Regia: Drew Goddard Cast: Chris Hemsworth, Dakota Johnson, Jeff Bridges, Nick Offerman, Cailee Spaeny Genere: Thriller Distributore: 20th Century Fox Uscita: 25 ottobre 2018 7 Uomini A Mollo Regia: Gilles Lellouche Cast: Mathieu Amalric, Guillaume Canet, Benoît Poelvoorde, Jean-hugues Anglade Genere: Commedia Distributore: Eagle Pictures Uscita: 20 dicembre 2018 '71 Regia: Yann Demange Cast: Jack O'connell, Sam Reid Genere: Thriller Distributore: Good Films Srl Uscita: 09 luglio 2015 77 Giorni Regia: Hantang Zhao Cast: Hantang Zhao, Yiyan Jiang Genere: Avventura Distributore: Mescalito Uscita: 15 maggio 2018 87 Ore Regia: Costanza Quatriglio Genere: Documentario Distributore: Cineama Uscita: 19 novembre 2015 A Beautiful Day Regia: Lynne Ramsay Cast: Joaquin Phoenix, Alessandro Nivola, Alex Manette, John Doman, Judith Roberts Genere: Thriller Distributore: Europictures Srl Uscita: 01 maggio 2018 A Bigger Splash Regia: Luca Guadagnino Cast: Ralph Fiennes, Dakota Johnson Genere: Drammatico Distributore: Lucky Red Uscita: 26 novembre 2015 3 Generations - Una Famiglia Quasi Perfetta Regia: Gaby Dellal Cast: Elle Fanning, Naomi Watts, Susan Sarandon, Tate Donovan, Maria Dizzia Genere: Commedia Distributore: Videa S.p.a. Uscita: 24 novembre 2016 40 Sono I Nuovi 20 Regia: Hallie Meyers-shyer Cast: Reese Witherspoon, Michael Sheen, Candice -

In Your Dreams

Core Apprenticeship Library Apprenticeship Sector: Arts & Culture Unit Guide: In Your Dreams In Your Dreams The In Your Dreams unit is a series of inquiry-driven lessons designed to boost students’ sophistication as nonfiction readers. The culminating zine project requires students to integrate information from multiple sources, selecting details to support a central idea. Students will also gain vocabulary skills, including the use of word roots and affixes and an awareness of words’ connotations. Students will learn to “read like writers,” which requires thinking about the choices authors have made in terms of content, format, and word choice. Unit Standards and Objectives Standard #1: Citizen Schools students will prepare a clear written communication. Standard #2: CCSS.RI.6.1: Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text. Standard #3: CCSS.RI.6.2: Determine a central idea of a text and how it is conveyed through details. Standard #4: CCSS.RI.6.4: Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative, connotative, and technical meanings Standard #5: CCSS.RI.6.6: Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text and explain how it is conveyed in the text. Lesson Objectives: ● SWBAT identify the big idea of a text. ● SWBAT identify two details that support the big idea of a text. ● SWBAT provide a brief summary of the text. ● SWBAT read like a writer by thinking about why the author made the choices s/he did, and what the author is trying to get the reader to think, feel, or understand while they are reading.