Killing Ourselves Is Not Subversive AM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socially Engaged Art Project to the Curb and B.Pdf

SPRING ZINE-ING - TO THE CURB AND BEYOND JUNE 2021 OONAGH E. FITZGERALD Art Making, Sharing, Performing & Completing in the Neighbourhood as we Emerge from the Pandemic A SOCIAL ENGAGED ART PROJECT ZINES DIY self-published, independent, pamphlets, magazines, artbook, comics etc. Recent examples: skater, graffiti, Black Lives Matter Touchable, affordable, personal, raw Artists: Walter Moodie, Emmanuel Okot, Ross Le Blanc, Mikaela Kautkzy, Venise 410B, Raphael Fitzgerald-Biernath https://www.theguardian.com/music/gallery/2013/ jun/30/punk-music “riot grrrl no. 1, Molly Neuman and Allison Wolfe, July 1991. All you need to riot grrrl 1980’S - start a counter-culture revolution is a few sheets of A4 paper, a typewriter, a 90’S photocopier, a Sharpie and some old magazines. Zines were fast to produce and easy to distribute. My Life with Evan Dando, Popstar, Kathleen Hanna. In 1993, Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna created a visually raw mock-psychotic fanzine … to explore violence, objectification, misogyny and the politics of creative success… inspired in part by rage and horror at the anti-feminist [Montreal] mass … [murder]”. A VOICE FOR “Slant no. 5, Mimi Thi Ngyuen, 1996. ANYONE & riot grrrl was criticised for failing to be truly inclusive, or EVERYONE transcending its status as a predominantly white, middle-class movement. But there were riot grrrls of colour, who in classic punk style seized back the conversation on race. Zines such as Slant, Bamboo Girl, Evolution of a Race Riot and Chop Suey Spex refused the identity, as Ngyuen puts it, -

Download PDF > Riot Grrrl \\ 3Y8OTSVISUJF

LWSRQOQGSW3L / Book ~ Riot grrrl Riot grrrl Filesize: 8.18 MB Reviews Unquestionably, this is actually the very best work by any article writer. It usually does not price a lot of. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Augustine Pfannerstill) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GOKP10TMWQNH / Kindle ~ Riot grrrl RIOT GRRRL To download Riot grrrl PDF, make sure you refer to the button under and download the document or gain access to other information which might be related to RIOT GRRRL book. Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 54. Chapters: Kill Rock Stars, Sleater-Kinney, Tobi Vail, Kathleen Hanna, Lucid Nation, Jessicka, Carrie Brownstein, Kids Love Lies, G. B. Jones, Sharon Cheslow, The Shondes, Jack O Jill, Not Bad for a Girl, Phranc, Bratmobile, Fih Column, Caroline Azar, Bikini Kill, Times Square, Jen Smith, Nomy Lamm, Huggy Bear, Karen Finley, Bidisha, Kaia Wilson, Emily's Sassy Lime, Mambo Taxi, The Yo-Yo Gang, Ladyfest, Bangs, Shopliing, Mecca Normal, Voodoo Queens, Sister George, Heavens to Betsy, Donna Dresch, Allison Wolfe, Billy Karren, Kathi Wilcox, Tattle Tale, Sta-Prest, All Women Are Bitches, Excuse 17, Pink Champagne, Rise Above: The Tribe 8 Documentary, Juliana Luecking, Lungleg, Rizzo, Tammy Rae Carland, The Frumpies, Lisa Rose Apramian, List of Riot Grrl bands, 36-C, Girl Germs, Cold Cold Hearts, Frightwig, Yer So Sweet, Direction, Viva Knievel. Excerpt: Riot grrrl was an underground feminist punk movement based in Washington, DC, Olympia, Washington, Portland, Oregon, and the greater Pacific Northwest which existed in the early to mid-1990s, and it is oen associated with third-wave feminism (it is sometimes seen as its starting point). -

January/February 2014 Vol

The Gainesville Iguana January/February 2014 Vol. 28, Issue 1/2 CMC SpringBoard fundraiser March 21 by Joe Courter The date for the Civic Media Center’s annual SpringBoard fundraiser is Friday evening, March 21. There will be a new location this year after last year’s venture at Prairie Creek Lodge, and that is in the heart of Down- town Gainesville at the Wooly, 20 N. Main St., a new event venue in what is the old Woolworth building next to and run by The Top restaurant. There will be food from various area restaurants, a si- lent auction and raffle items, and awards. The speaker this year is an old friend of McDonald’s workers and allies strike on July 31, 2013 in Chicago. Photo by Steve Rhodes. the CMC, David Barsamian, the founder and main man with Alternative Radio, who said he is “honored to follow in No- 2013 in review: Aiming higher, am’s footsteps.” labor tries new angles and alliances That is fitting because Alternative Ra- by Jenny Brown ment that jobs that once paid the bills, dio has made a special effort to archive from bank teller to university instructor, Noam Chomsky talks since its founding This article originally appeared in the now require food stamps and Medicaid to in 1989. David’s radio show was a staple January 2014 issue of LaborNotes. You supplement the wages of those who work See SPRINGBOARD, p. 2 can read the online version, complete with informative links and resources, at www. every day. labornotes.org/2013/12/2013-review- California Walmart worker Anthony INSIDE .. -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC). -

The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing Academic Programs and Advising 2020 The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot Adam Clark Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/studentawards Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Adam, "The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot" (2020). Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing. 16. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/studentawards/16 This Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Programs and Advising at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adam Clark Victoria Malawey, Gender & Music The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot “We’re gonna take over the punk scene for feminists” -Kathleen Hanna Although they share feminist ideals, the Russian art collective Pussy Riot distinguishes themselves from the U.S.-based Riot Grrrl Movement, as exemplified by the band Bikini Kill, because of their location-specific protest work in Moscow. Understanding how Pussy Riot is both similar to and different from Riot Grrrl is important for contextualizing the way we think about diverse, transnational feminisms so that we may develop more inclusive and nuanced ways in conceptualizing these feminisms in the future. While Pussy Riot shares similar ideals championed by Bikini Kill in the Riot Grrrl movement, they have temporal and location-specific activisms and each group has their own ways of protesting injustices against women and achieving their unique goals. -

Disidentification and Evolution Within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2012 (R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College Recommended Citation Estenson, Lilly, "(R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism" (2012). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 94. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/94 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (R)EVOLUTION GRRRL STYLE NOW: DISIDENTIFICATION AND EVOLUTION WITHIN RIOT GRRRL FEMINISM by LILLY ESTENSON SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR CHRIS GUZAITIS PROFESSOR KIMBERLY DRAKE April 20, 2012 Estenson 1 Table of Contents Introduction ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Chapter 1: Contextualizing Riot Grrrl Feminism ---------------------------------------- 20 Chapter 2: Feminist Praxis in the Original Riot Grrrl Movement (1990-96) ------- 48 Chapter 3: Subcultural Disidentification and Contemporary Riot Grrrl Praxis --- 72 Conclusion ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 97 Works Cited ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

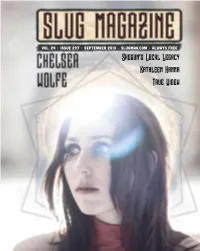

Shogun's Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow

Vol. 24 • Issue 297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com • Always Free Shogun’s Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow slugmag.com 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround slugmag.com 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 24 • Issue #297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com facebook.com/SLUG.Mag @SLUGMag @SLUGMag youtube.com/user/SLUGMagazine Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Manager: Editor: Angela H. Brown Karamea Puriri Managing Editor: Esther Meroño Marketing Team: Ischa B., Sabrina Costello, Editorial Assistant: Alexander Ortega Kristina Sandi, Brooklyn Ottens, Angella Luci- Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan sano, Nicole Roccanova, Raffi Shahinian, Vic- Digital Content Coordinator: Cody Kirkland toria Loveless, Zac Freeman, Cassie Anderson, Copy Editing Team: Esther Meroño, Alexan- Cassie Loveless, Shley Kinser, Matt Brunk, Robin der Ortega, Mary E. Duncan, Cody Kirkland, Sessions, Carl Acheson, Chandler Hunt Johnathan Ford, Alex Cragun, Rachel Miller, Ka- Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer tie Bald, Liz Phillips, Allison Shephard, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Shawn Soward Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Tony Cover Designer: Joshua Joye Bassett, Nancy Burkhart, Adam Okeefe, Ryan Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Worwood, John Ford, Matt Pothier, Phil Cannon, Design Team: Eleanor Scholz, BJ Viehl, Lenny Tim Kronenberg, Justin Nelson-Carruth, Xkot Riccardi, Chad Pinckney, Mason Rodrickc Toxsik, Nancy Perkins Ad Designers: Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Christian Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Eric Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, Mariah Sapp, Brad Barker, Paden Bischoff, Maggie Mann-Mellus, James Orme, Lance Saunders, Zukowski, Thy Doan, KJ Jackett, Nicholas Dowd, Bryer Wharton, Peter Fryer, James Bennett, Ricky Nick Ketterer Vigil, Gavin Hoffman, Esther Meroño, Rebecca Website Design: Kate Colgan Vernon, Jimmy Martin, Ben Trentelman, Princess Office Interns: Carl Acheson, Robin Sessions, Kennedy, Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Cody Hudson, Alex Cragun, Chandler Hunt Shawn Mayer, Dean O. -

'Race Riot' Within and Without 'The Grrrl One'; Ethnoracial Grrrl Zines

The ‘Race Riot’ Within and Without ‘The Grrrl One’; Ethnoracial Grrrl Zines’ Tactical Construction of Space by Addie Shrodes A thesis presented for the B. A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2012 © March 19, 2012 Addie Cherice Shrodes Acknowledgements I wrote this thesis because of the help of many insightful and inspiring people and professors I have had the pleasure of working with during the past three years. To begin, I am immensely indebted to my thesis adviser, Prof. Gillian White, firstly for her belief in my somewhat-strange project and her continuous encouragement throughout the process of research and writing. My thesis has benefitted enormously from her insightful ideas and analysis of language, poetry and gender, among countless other topics. I also thank Prof. White for her patient and persistent work in reading every page I produced. I am very grateful to Prof. Sara Blair for inspiring and encouraging my interest in literature from my first Introduction to Literature class through my exploration of countercultural productions and theories of space. As my first English professor at Michigan and continual consultant, Prof. Blair suggested that I apply to the Honors program three years ago, and I began English Honors and wrote this particular thesis in a large part because of her. I owe a great deal to Prof. Jennifer Wenzel’s careful and helpful critique of my thesis drafts. I also thank her for her encouragement and humor when the thesis cohort weathered its most chilling deadlines. I am thankful to Prof. Lucy Hartley, Prof. -

Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: the Riot Grrrl Revolution As a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance Summit J

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2016 Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: The Riot Grrrl Revolution as a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance Summit J. Starr The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Starr, Summit J., "Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: The Riot Grrrl Revolution as a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance" (2016). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 7022. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/7022 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2016 Summit J. Starr The College of Wooster Conceptualizing Female Punk in the Theatre: The Riot Grrrl Revolution as a Radical Force to Inspire a Devised Solo Performance by Summit J. Starr Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Senior Independent Study Requirement Theatre and Dance 451 - 452 Advised by Jimmy A. Noriega Department of Theatre & Dance March 28th, 2016 1 | Starr Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………….………………3 Acknowledgements……………………………….………….……….……………..4 Introduction and Literature Review …………...…………………………….…….5 Chapter One: Technique and Aesthetics……...……………………….…………..18 Chapter Two: Devising Concept……………………………………….…………..31 Chapter Three: Reflection…………………………………………………………...46 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………63 Appendix A…………………………………………………………………………..65 Bibliography and Works Cited ……………………………………………………..97 2 | Starr Abstract My Independent Study focuses on the technique and aesthetic of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, and how those elements effectively continued the 90s underground punk scene. -

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33

Allison Wolfe Interviewed by John Davis Los Angeles, California June 15, 2017 0:00:00 to 0:38:33 ________________________________________________________________________ 0:00:00 Davis: Today is June 15th, 2017. My name is John Davis. I’m the performing arts metadata archivist at the University of Maryland, speaking to Allison Wolfe. Wolfe: Are you sure it’s the 15th? Davis: Isn’t it? Yes, confirmed. Wolfe: What!? Davis: June 15th… Wolfe: OK. Davis: 2017. Wolfe: Here I am… Davis: Your plans for the rest of the day might have changed. Wolfe: [laugh] Davis: I’m doing research on fanzines, particularly D.C. fanzines. When I think of you and your connection to fanzines, I think of Girl Germs, which as far as I understand, you worked on before you moved to D.C. Is that correct? Wolfe: Yeah. I think the way I started doing fanzines was when I was living in Oregon—in Eugene, Oregon—that’s where I went to undergrad, at least for the first two years. So I went off there like 1989-’90. And I was there also the year ’90-’91. Something like that. For two years. And I met Molly Neuman in the dorms. She was my neighbor. And we later formed the band Bratmobile. But before we really had a band going, we actually started doing a fanzine. And even though I think we named the band Bratmobile as one of our earliest things, it just was a band in theory for a long time first. But we wanted to start being expressive about our opinions and having more of a voice for girls in music, or women in music, for ourselves, but also just for things that we were into. -

Music & Arts Festival Calgary, Alberta

MUSIC & ARTS FESTIVAL CALGARY, ALBERTA SLED ISLAND STAFF Adele Brunnhofer – Film Program Coordinator Phil Cimolai – Technical Director TABLE OF Colin Gallant – Web Content & Social Media Vanessa Gloux – Promotions Coordinator CONTENTS Nivedita Iyer – Merchandise Coordinator Megan Jorgensen-Nelson – Artist Logistics Coordinator Briana Mallar McLeod – Volunteer Coordinator Drew Marshall – Marketing Coordinator 07 CURATOR/FESTIVAL MANAGER NOTES Nastassia Mihalicz - Sustainability Assistant Erin Nolan – Transport Director 08 FILM Rachel Park – Graphic Designer Shawn Petsche – Festival Manager 11 ART Josh Ruck – Poster Show Curator Lauren Ruckdaeschel – Box-office Coordinator 14 COMEDY Stephanie Russell – Assistant Volunteer Coordinator 17 SPECIAL EVENTS Becky Salmond – Partnership Assistant Maud Salvi - Executive Director 23 BANDS/MUSIC Jodie Rose – Visual Arts Coordinator/Curator Paisley V. Sim – Immigration Coordinator 37 PULLOUT SCHEDULE Colin Smith – Sustainability Coordinator Justin Smith – Hospitality Coordinator 67 EAST VILLAGE Kali Urquhart – Billet Coordinator Evan Wilson – Comedy Curator 69 GREEN ISLAND Rebecca Zahn – All Ages Coordinator 73 DISCOUNT GUIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 76 THANKS Christina Colenutt Chris Gokiert 78 SPONSORS Brian Milne Dan Northfield Sarmad Rizvi Terry Rock Chad Saunders Rob Schultz Craig Stenhouse SLED ISLAND FILM COMMITTEE Adele Brunnhofer HOW TO ATTEND Jesse Cumming Felicia Glatz SLED ISLAND Catie St Jacques Ted Stenson RETURNING FOR THE EIGHTH YEAR, SLED ISLAND IS AN ANNUAL INDEPENDENT Evan Wilson MUSIC AND ARTS FESTIVAL FEATURING OVER 200 BANDS PLUS FILM, VISUAL VISUAL DIRECTOR ART, COMEDY AND SPECIAL EVENTS ACROSS 30+ VENUES IN CALGARY, ALBERTA Dylan Smith FROM JUNE 18-22, 2014. WE OFFER A NUMBER OF WAYS TO EXPLORE AND DISCOVER THIS STAGGERING AMOUNT OF MUSIC AND ART AND EVERYTHING BOOKING ELSE THAT GOES DOWN OVER THESE FIVE JAM-PACKED DAYS. -

REFORMULATING the RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT: GRRRL RIOT the REFORMULATING : Riot Grrrl, Lyrics, Space, Sisterhood, Kathleen Hanna

REFORMULATING THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT: SPACE AND SISTERHOOD IN KATHLEEN HANNA’S LYRICS Soraya Alonso Alconada Universidad del País Vasco (UPV/EHU) [email protected] Abstract Music has become a crucial domain to discuss issues such as gender, identities and equality. With this study I aim at carrying out a feminist critical discourse analysis of the lyrics by American singer and songwriter Kathleen Hanna (1968-), a pioneer within the underground punk culture and head figure of the Riot Grrrl movement. Covering relevant issues related to women’s conditions, Hanna’s lyrics put gender issues at the forefront and become a sig- nificant means to claim feminism in the underground. In this study I pay attention to the instances in which Hanna’s lyrics in Bikini Kill and Le Tigre exhibit a reading of sisterhood and space and by doing so, I will discuss women’s invisibility in underground music and broaden the social and cultural understanding of this music. Keywords: Riot Grrrl, lyrics, space, sisterhood, Kathleen Hanna. REFORMULANDO EL MOVIMIENTO RIOT GRRRL: ESPACIO Y SORORIDAD EN LAS LETRAS DE KATHLEEN HANNA Resumen 99 La música se ha convertido en un espacio en el que debatir temas como el género, la iden- tidad o la igualdad. Con este trabajo pretendo llevar a cabo un análisis crítico del discurso con perspectiva feminista de las letras de canciones de Kathleen Hanna (1968-), cantante y compositora americana, pionera del movimiento punk y figura principal del movimiento Riot Grrrl. Cubriendo temas relevantes relacionados con la condición de las mujeres, las letras de Hanna sitúan temas relacionados con el género en primera línea y se convierten en un medio significativo para reclamar el feminismo en la música underground.