An Interview with Sara Landeau, American Music Review, Vol. XLIX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation “We’re Punk as Fuck and Fuck like Punks:”* Queer-Feminist Counter-Cultures, Punk Music and the Anti-Social Turn in Queer Theory Verfasserin Mag.a Phil. Maria Katharina Wiedlack angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. Phil.) Wien, Jänner 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ. Prof.in Dr.in Astrid Fellner Earlier versions and parts of chapters One, Two, Three and Six have been published in the peer-reviewed online journal Transposition: the journal 3 (Musique et théorie queer) (2013), as well as in the anthologies Queering Paradigms III ed. by Liz Morrish and Kathleen O’Mara (2013); and Queering Paradigms II ed. by Mathew Ball and Burkard Scherer (2012); * The title “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks” is a line from the song Burn your Rainbow by the Canadian queer-feminist punk band the Skinjobs on their 2003 album with the same name (released by Agitprop Records). Content 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. “To Sir With Hate:” A Liminal History of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock ….………………………..…… 21 3. “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks:” Punk Rock, Queerness, and the Death Drive ………………………….………….. 69 4. “Challenge the System and Challenge Yourself:” Queer-Feminist Punk Rock’s Intersectional Politics and Anarchism……...……… 119 5. “There’s a Dyke in the Pit:” The Feminist Politics of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock……………..…………….. 157 6. “A Race Riot Did Happen!:” Queer Punks of Color Raising Their Voices ..……………..………… ………….. 207 7. “WE R LA FUCKEN RAZA SO DON’T EVEN FUCKEN DARE:” Anger, and the Politics of Jouissance ……….………………………….…………. -

Download PDF > Riot Grrrl \\ 3Y8OTSVISUJF

LWSRQOQGSW3L / Book ~ Riot grrrl Riot grrrl Filesize: 8.18 MB Reviews Unquestionably, this is actually the very best work by any article writer. It usually does not price a lot of. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Augustine Pfannerstill) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GOKP10TMWQNH / Kindle ~ Riot grrrl RIOT GRRRL To download Riot grrrl PDF, make sure you refer to the button under and download the document or gain access to other information which might be related to RIOT GRRRL book. Reference Series Books LLC Jan 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 249x189x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 54. Chapters: Kill Rock Stars, Sleater-Kinney, Tobi Vail, Kathleen Hanna, Lucid Nation, Jessicka, Carrie Brownstein, Kids Love Lies, G. B. Jones, Sharon Cheslow, The Shondes, Jack O Jill, Not Bad for a Girl, Phranc, Bratmobile, Fih Column, Caroline Azar, Bikini Kill, Times Square, Jen Smith, Nomy Lamm, Huggy Bear, Karen Finley, Bidisha, Kaia Wilson, Emily's Sassy Lime, Mambo Taxi, The Yo-Yo Gang, Ladyfest, Bangs, Shopliing, Mecca Normal, Voodoo Queens, Sister George, Heavens to Betsy, Donna Dresch, Allison Wolfe, Billy Karren, Kathi Wilcox, Tattle Tale, Sta-Prest, All Women Are Bitches, Excuse 17, Pink Champagne, Rise Above: The Tribe 8 Documentary, Juliana Luecking, Lungleg, Rizzo, Tammy Rae Carland, The Frumpies, Lisa Rose Apramian, List of Riot Grrl bands, 36-C, Girl Germs, Cold Cold Hearts, Frightwig, Yer So Sweet, Direction, Viva Knievel. Excerpt: Riot grrrl was an underground feminist punk movement based in Washington, DC, Olympia, Washington, Portland, Oregon, and the greater Pacific Northwest which existed in the early to mid-1990s, and it is oen associated with third-wave feminism (it is sometimes seen as its starting point). -

January/February 2014 Vol

The Gainesville Iguana January/February 2014 Vol. 28, Issue 1/2 CMC SpringBoard fundraiser March 21 by Joe Courter The date for the Civic Media Center’s annual SpringBoard fundraiser is Friday evening, March 21. There will be a new location this year after last year’s venture at Prairie Creek Lodge, and that is in the heart of Down- town Gainesville at the Wooly, 20 N. Main St., a new event venue in what is the old Woolworth building next to and run by The Top restaurant. There will be food from various area restaurants, a si- lent auction and raffle items, and awards. The speaker this year is an old friend of McDonald’s workers and allies strike on July 31, 2013 in Chicago. Photo by Steve Rhodes. the CMC, David Barsamian, the founder and main man with Alternative Radio, who said he is “honored to follow in No- 2013 in review: Aiming higher, am’s footsteps.” labor tries new angles and alliances That is fitting because Alternative Ra- by Jenny Brown ment that jobs that once paid the bills, dio has made a special effort to archive from bank teller to university instructor, Noam Chomsky talks since its founding This article originally appeared in the now require food stamps and Medicaid to in 1989. David’s radio show was a staple January 2014 issue of LaborNotes. You supplement the wages of those who work See SPRINGBOARD, p. 2 can read the online version, complete with informative links and resources, at www. every day. labornotes.org/2013/12/2013-review- California Walmart worker Anthony INSIDE .. -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC). -

The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing Academic Programs and Advising 2020 The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot Adam Clark Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/studentawards Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Adam, "The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot" (2020). Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing. 16. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/studentawards/16 This Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Programs and Advising at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adam Clark Victoria Malawey, Gender & Music The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot “We’re gonna take over the punk scene for feminists” -Kathleen Hanna Although they share feminist ideals, the Russian art collective Pussy Riot distinguishes themselves from the U.S.-based Riot Grrrl Movement, as exemplified by the band Bikini Kill, because of their location-specific protest work in Moscow. Understanding how Pussy Riot is both similar to and different from Riot Grrrl is important for contextualizing the way we think about diverse, transnational feminisms so that we may develop more inclusive and nuanced ways in conceptualizing these feminisms in the future. While Pussy Riot shares similar ideals championed by Bikini Kill in the Riot Grrrl movement, they have temporal and location-specific activisms and each group has their own ways of protesting injustices against women and achieving their unique goals. -

Disidentification and Evolution Within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2012 (R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism Lilly Estenson Scripps College Recommended Citation Estenson, Lilly, "(R)Evolution Grrrl Style Now: Disidentification and Evolution within Riot Grrrl Feminism" (2012). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 94. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/94 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (R)EVOLUTION GRRRL STYLE NOW: DISIDENTIFICATION AND EVOLUTION WITHIN RIOT GRRRL FEMINISM by LILLY ESTENSON SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR CHRIS GUZAITIS PROFESSOR KIMBERLY DRAKE April 20, 2012 Estenson 1 Table of Contents Introduction ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Chapter 1: Contextualizing Riot Grrrl Feminism ---------------------------------------- 20 Chapter 2: Feminist Praxis in the Original Riot Grrrl Movement (1990-96) ------- 48 Chapter 3: Subcultural Disidentification and Contemporary Riot Grrrl Praxis --- 72 Conclusion ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 97 Works Cited ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Issue L'essai COMME PRATIQUE ARTISTIQUE ARTS VISUELS #21 E

OCTOBRE 2011 Issue #21 L’ESSAITHE ESSAY COMME AS PRATIQUE ARTISTIQUEARTISTIC PRACTICE ARTS VISUELS head_issue_no21.indd 1 24.10.2011 15:31:59 The Organ * Concerts Halle/S. féminisme gender Sleater Kinney Müllstation*** The Lurkers Barcelone RIOT GRRRLS Rancid The Clash Kathleen Hanna Electrelane The Offspring* Bernard Heidsieck Beth Ditto PUNK ash* John Cage Alvin Lucier Bikini Kill X-Ray Spex deus* Le Tigre The Rezillos Sound Art The Gossip identity Sex Pistols* ALTERNATIVE Maryanne Amacher Buzzcocks MTV Pauline Oliveros Leipzig Berlin Sham 69 guide to alternative nation 120 minutes Circuit Bending The Vibrators* REM* Ray Cokes Vienne Pouvoir La volonté de savoir Discours Rhizome M. Foucault la différence / la différance Deleuze/Guattari Oscar Wilde Gabriel García Márquez H.V.Kleist DECONSTRUCTIVISME POST-STRUCTURALISME préjugés J.Derrida R. Barthes Hofstadter Franz Kafka Robert Musil Chris Marker Mythologies Logique L’Homme sans qualités Thomas Mann Edith Piaf Sans soleil J.S. Bach Bertolt Brecht EXISTENTIALISME Das musikalische Opfer Huis clos Sartre Camus THÉORIE CRITIQUE / Die Kunst der Fuge Friedrich Dürrenmatt Peter Handke L’Etre et le néant ÉCOLE DE FRANCFORT le théâtre absurde Sisyphos Heinrich Böll LITTÉRATURE Les mots T.W.Adorno Horkheimer APRÈS GUERRE Genève Max Frisch Dialectique de la Raison Homo Faber Samuel Beckett Ingeborg Bachmann Minima Moralia Stiller Thomas Bernhard En attendant Godot Nelly Sachs Günter Grass Elfriede Jelinek Alexander Kluge Cindy Sherman Agnès Varda Photo Alte Meister Fischli/Weiss Lisl Ponger Das -

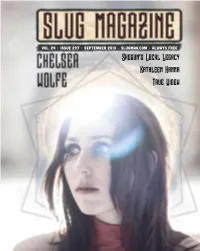

Shogun's Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow

Vol. 24 • Issue 297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com • Always Free Shogun’s Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow slugmag.com 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround slugmag.com 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 24 • Issue #297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com facebook.com/SLUG.Mag @SLUGMag @SLUGMag youtube.com/user/SLUGMagazine Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Manager: Editor: Angela H. Brown Karamea Puriri Managing Editor: Esther Meroño Marketing Team: Ischa B., Sabrina Costello, Editorial Assistant: Alexander Ortega Kristina Sandi, Brooklyn Ottens, Angella Luci- Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan sano, Nicole Roccanova, Raffi Shahinian, Vic- Digital Content Coordinator: Cody Kirkland toria Loveless, Zac Freeman, Cassie Anderson, Copy Editing Team: Esther Meroño, Alexan- Cassie Loveless, Shley Kinser, Matt Brunk, Robin der Ortega, Mary E. Duncan, Cody Kirkland, Sessions, Carl Acheson, Chandler Hunt Johnathan Ford, Alex Cragun, Rachel Miller, Ka- Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer tie Bald, Liz Phillips, Allison Shephard, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Shawn Soward Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Tony Cover Designer: Joshua Joye Bassett, Nancy Burkhart, Adam Okeefe, Ryan Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Worwood, John Ford, Matt Pothier, Phil Cannon, Design Team: Eleanor Scholz, BJ Viehl, Lenny Tim Kronenberg, Justin Nelson-Carruth, Xkot Riccardi, Chad Pinckney, Mason Rodrickc Toxsik, Nancy Perkins Ad Designers: Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Christian Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Eric Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, Mariah Sapp, Brad Barker, Paden Bischoff, Maggie Mann-Mellus, James Orme, Lance Saunders, Zukowski, Thy Doan, KJ Jackett, Nicholas Dowd, Bryer Wharton, Peter Fryer, James Bennett, Ricky Nick Ketterer Vigil, Gavin Hoffman, Esther Meroño, Rebecca Website Design: Kate Colgan Vernon, Jimmy Martin, Ben Trentelman, Princess Office Interns: Carl Acheson, Robin Sessions, Kennedy, Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Cody Hudson, Alex Cragun, Chandler Hunt Shawn Mayer, Dean O. -

Katalog Zur Ausstellung

ARCHIV DER JUGENDKULTUREN (HRSG.) DER Z/WEITE BLICK JUGENDKULTUREN UND DISKRIMINIERUNGEN Archiv der Jugendkulturen (Hrsg.) DER Z/WEITE BLICK JUGENDKULTUREN UND DISKRIMINIERUNGEN Ausstellungseröffnung im Archiv der Jugendkulturen e.V., Berlin, 2017, Foto: Boris Geilert IMPRESSUM Archiv der Jugendkulturen e. V. Fidicinstraße 3 10965 Berlin Tel. 030–6942934 Fax 030–6913016 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: www.jugendkulturen.de Autor*innen / Redaktion: DJ Freshfluke, Jule Naima Fröhlich, Martin Gegenheimer, Florian Hofbauer, Tino Kandal, Edyta Kopitzki, Svetla Koynova, Bianca Loy, Gabriele Rohmann, Lisa Schug, Farina Wäcker Illustrationen: Gabriel S Moses, www.gabsmoses.com Lektorat: Berlin Lektorat und Nadine Marcinczik © Archiv der Jugendkulturen e. V. 2018 Die Veröffentlichung stellt keine Meinungsäußerung des BMFSFJ bzw. des BAFzA dar. Für inhaltliche Aussagen trägt der Autor/die Autorin bzw. tragen die Autoren/Autorinnen die Verantwortung. VORWORT Jugendkulturen sind wichtige Orte für (überwiegend) junge Sexismus und Homo- und Transfeindlichkeit – aber auch Menschen, an denen sie ihren Gedanken, Einstellungen, Hal- positive Aspekte wie jugendkulturelle Initiativen oder Pop- tungen, Reflexionen über sich und die Welt in Kleidung, Spra- Künstler*innen, die sich gegen Diskriminierungen in ihren che, Musik und Medien kreativen Ausdruck verleihen können. Szenen oder im Mainstream wehren und sich auf diese Weise Sie bieten Heranwachsenden Möglichkeiten, künstlerisch, zivilgesellschaftlich für die Gleichwertigkeit von Menschen ein- gesellschaftlich -

For the Love of It?: Zine Writing and the Study Of

FOR THE LOVE OF IT?: ZINE WRITING AND THE STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY AMATEUR WORK A Dissertation by EMILY SARA HOEFLINGER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Mary Ann O’Farrell Committee Members, Sally Robinson Giovanna Del Negro Joan Wolf Head of Department, Maura Ives May 2016 Major Subject: English Copyright 2016 Emily Sara Hoeflinger ABSTRACT In this project, I am examining zines in relation to the question of contemporary amateurism. With the onset of Web 2.0 came a space for new forms of amateur work, but this new work hasn’t been addressed as “amateur,” which has revealed a problem between what theorists know the amateur to be and what has been embraced by mainstream culture. This oversimplification of the definition of amateurism seems to threaten the integrity of amateur work in general. I analyze the concepts “transparency” and “distance” and show that both highlight the need for preserving the amateur. I confront the notion of “for the love it” by interrogating the boundaries that zine writers have established and the misperception that zine work somehow remains on the fringe of capitalist culture. Moreover, I identify the Pro Am (professional amateur) as the most significant contemporary amateur figure because it directly challenges not only what it means to be professional, but also what it means to be amateur. By examining perzines and glossies, I argue that while “for the love of it” has been downplayed or even ignored, internal rewards are still an important factor in what makes an act amateur and that external rewards don’t always have to be monetary. -

18 Transgender CON by Chris Angel Murphy 18 Alcoholism, the Thinking Disease by G-O Digillio TENTS 32 Living out by Sally Sheklow

1 TWO MOTHERS – Germany – Director, Anne Zohra Berrached REACHING FOR THE MOON – Brazil - Director, Bruno Barreto Enjoy a great line-up of LGBT films, including our annual celebration of diversity in cinema, the GAY!La screenings - for HIM and for HER - and party! Palm Springs International Film Festival features eleven unforgettable days of screenings, tributes and special events in the gorgeous desert setting of Palm Springs. With more than 185 films from over 70 different countries, it’s a singular celebration of the best of international and American cinema. Box Office Opens December 26, 2013 Special hotel rates available at psfilmfest.org/participate/travel/ Reel-Deal Six Packs & Special Event tickets NOW on sale online at: psfilmfest.org or call (760) 778-8979 title SPONSOR major SPONSORS is a proud sponsor of the Palm Springs International Film Festival Lesbian News Magazine | December 2013 | www.LesbianNews.com Subscribe To Lesbian News NOW With every 1 year subscription receive this LN perk. Subscribe to Lesbian News on your iPad & iPhone and access the magazine as well as LN digital extras each month. Advertise in LN 1.800.458.9888 3 December 2013 Features 14 Theorhetorically Speaking By Nikki McCauley 18 Transgender CON By Chris Angel Murphy 18 Alcoholism, The Thinking Disease By G-O Digillio TENTS 32 Living Out By Sally Sheklow 33 Positive Reflections Inside LN By Dian Katz, MS 42 Words That Make Sense 11 POETRY By Toni Hart 13 MUSIC 19 LIFE COACH’S CORNER 19 QUEERLY QUESTIONING Lifestyles 20 MOVIES EYE C 22 LOLs 10 Politically -

'Race Riot' Within and Without 'The Grrrl One'; Ethnoracial Grrrl Zines

The ‘Race Riot’ Within and Without ‘The Grrrl One’; Ethnoracial Grrrl Zines’ Tactical Construction of Space by Addie Shrodes A thesis presented for the B. A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2012 © March 19, 2012 Addie Cherice Shrodes Acknowledgements I wrote this thesis because of the help of many insightful and inspiring people and professors I have had the pleasure of working with during the past three years. To begin, I am immensely indebted to my thesis adviser, Prof. Gillian White, firstly for her belief in my somewhat-strange project and her continuous encouragement throughout the process of research and writing. My thesis has benefitted enormously from her insightful ideas and analysis of language, poetry and gender, among countless other topics. I also thank Prof. White for her patient and persistent work in reading every page I produced. I am very grateful to Prof. Sara Blair for inspiring and encouraging my interest in literature from my first Introduction to Literature class through my exploration of countercultural productions and theories of space. As my first English professor at Michigan and continual consultant, Prof. Blair suggested that I apply to the Honors program three years ago, and I began English Honors and wrote this particular thesis in a large part because of her. I owe a great deal to Prof. Jennifer Wenzel’s careful and helpful critique of my thesis drafts. I also thank her for her encouragement and humor when the thesis cohort weathered its most chilling deadlines. I am thankful to Prof. Lucy Hartley, Prof.