Print/Download Entire Issue (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson Jr. Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Horace E. Anderson, Jr., No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us, 20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 (2011), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/818/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Bitin' Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson, Jr: I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act's Regulation of Copying ..................................................................................... 119 II. Impact of Technology ................................................................... 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying ........... 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap ......... 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying ................................................................. 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm ............................................... -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

January/February 2014 Vol

The Gainesville Iguana January/February 2014 Vol. 28, Issue 1/2 CMC SpringBoard fundraiser March 21 by Joe Courter The date for the Civic Media Center’s annual SpringBoard fundraiser is Friday evening, March 21. There will be a new location this year after last year’s venture at Prairie Creek Lodge, and that is in the heart of Down- town Gainesville at the Wooly, 20 N. Main St., a new event venue in what is the old Woolworth building next to and run by The Top restaurant. There will be food from various area restaurants, a si- lent auction and raffle items, and awards. The speaker this year is an old friend of McDonald’s workers and allies strike on July 31, 2013 in Chicago. Photo by Steve Rhodes. the CMC, David Barsamian, the founder and main man with Alternative Radio, who said he is “honored to follow in No- 2013 in review: Aiming higher, am’s footsteps.” labor tries new angles and alliances That is fitting because Alternative Ra- by Jenny Brown ment that jobs that once paid the bills, dio has made a special effort to archive from bank teller to university instructor, Noam Chomsky talks since its founding This article originally appeared in the now require food stamps and Medicaid to in 1989. David’s radio show was a staple January 2014 issue of LaborNotes. You supplement the wages of those who work See SPRINGBOARD, p. 2 can read the online version, complete with informative links and resources, at www. every day. labornotes.org/2013/12/2013-review- California Walmart worker Anthony INSIDE .. -

Cecil Taylor 3 Phasis Mp3, Flac, Wma

Cecil Taylor 3 Phasis mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: 3 Phasis Country: US Released: 1979 Style: Free Jazz, Avantgarde, Free Improvisation MP3 version RAR size: 1205 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1983 mb WMA version RAR size: 1218 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 556 Other Formats: AHX MMF AC3 DXD MP4 XM MP2 Tracklist A Side One 28:22 B Side Two 28:50 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Recorded Anthology Of American Music, Inc. Copyright (c) – Recorded Anthology Of American Music, Inc. Recorded At – Columbia Recording Studios Mastered At – Sterling Sound Credits Alto Saxophone – Jimmy Lyons Artwork [Cover Art] – Paul Jenkins Bass – Sirone Design [Cover] – Michael Sonino Drums – Ronald Shannon Jackson Engineer [Assistant Recording] – Ken Robertson Engineer [Recording, Editing, And Mixing] – Don Puluse Mastered By – Ted Jensen Photography By – Marc Brasz Piano – Cecil Taylor Producer – Sam Parkins Trumpet – Raphé Malik* Violin – Ramsey Ameen Notes Recorded in April 1978 at Columbia Recording Studios, 30th Street, New York, NY. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year New World 80303-2, NW Cecil 3 Phasis (CD, 80303-2, NW Records, New US 1996 303-2 Taylor Album, RE) 303-2 World Records Cecil 3 Phasis (CD, New World NW 303-2 NW 303-2 US Unknown Taylor Album, RE) Records Related Music albums to 3 Phasis by Cecil Taylor Jazz Cecil Taylor - Innovations Jazz Cecil Taylor - Great Paris Concert «2» Rock dt's - Widow Of An All-American Jazz Cecil Taylor Unit - Akisakila - Cecil Taylor Unit In Japan Jazz Cecil Taylor / Buell Neidlinger - New York City R&B Jazz Cecil Taylor - Conquistador! Jazz Cecil Taylor - The World Of Cecil Taylor Jazz Cecil Taylor - Buell Neidlinger - New York City R&B Jazz Cecil Taylor Trio And Quintet - Love For Sale Jazz Cecil Taylor / Charles Tolliver / Grachan Moncur / Archie Shepp - The New Breed. -

Hamburgs Top-821-Hitliste

Hamburgs Top‐821‐Hitliste Rang Wird wann gespielt? Name des Songs Interpret 821 2010‐04‐03 04:00:00 EVERYBODY (BACKSTREET'S BACK) BACKSTREET BOYS 820 2010‐04‐03 04:03:41 GET MY PARTY ON SHAGGY 819 2010‐04‐03 04:07:08 EIN EHRENWERTES HAUS UDO JÜRGENS 818 2010‐04‐03 04:10:34 BOAT ON THE RIVER STYX 817 2010‐04‐03 04:13:41 OBSESSION AVENTURA 816 2010‐04‐03 04:27:15 MANEATER DARYL HALL & JOHN OATES 815 2010‐04‐03 04:31:22 IN MY ARMS KYLIE MINOGUE 814 2010‐04‐03 04:34:52 AN ANGEL KELLY FAMILY 813 2010‐04‐03 04:38:34 HIER KOMMT DIE MAUS STEFAN RAAB 812 2010‐04‐03 04:41:47 WHEN DOVES CRY PRINCE 811 2010‐04‐03 04:45:34 TI AMO HOWARD CARPENDALE 810 2010‐04‐03 04:49:29 UNDER THE SURFACE MARIT LARSEN 809 2010‐04‐03 04:53:33 WE ARE THE PEOPLE EMPIRE OF THE SUN 808 2010‐04‐03 04:57:26 MICHAELA BATA ILLC 807 2010‐04‐03 05:00:29 I NEED LOVE L.L. COOL J. 806 2010‐04‐03 05:03:23 I DON'T WANT TO MISS A THING AEROSMITH 805 2010‐04‐03 05:07:09 FIGHTER CHRISTINA AGUILERA 804 2010‐04‐03 05:11:14 LEBT DENN DR ALTE HOLZMICHEL NOCH...? DE RANDFICHTEN 803 2010‐04‐03 05:14:37 WHO WANTS TO LIVE FOREVER QUEEN 802 2010‐04‐03 05:18:50 THE WAY I ARE TIMBALAND FEAT. KERI HILSON 801 2010‐04‐03 05:21:39 FLASH FOR FANTASY BILLY IDOL 800 2010‐04‐03 05:35:38 GIRLFRIEND AVRIL LAVIGNE 799 2010‐04‐03 05:39:12 BETTER IN TIME LEONA LEWIS 798 2010‐04‐03 05:42:55 MANOS AL AIRE NELLY FURTADO 797 2010‐04‐03 05:46:14 NEMO NIGHTWISH 796 2010‐04‐03 05:50:19 LAUDATO SI MICKIE KRAUSE 795 2010‐04‐03 05:53:39 JUST SAY YES SNOW PATROL 794 2010‐04‐03 05:57:41 LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANASTACIA 793 -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Lockett, P.W. (1988). Improvising pianists : aspects of keyboard technique and musical structure in free jazz - 1955-1980. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/8259/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] IMPROVISING PIANISTS: ASPECTS OF KEYBOARD TECHNIQUE AND MUSICAL STRUCTURE IN FREE JAll - 1955-1980. Submitted by Mark Peter Wyatt Lockett as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University Department of Music May 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No I List of Figures 3 IIListofRecordings............,........ S III Acknowledgements .. ..... .. .. 9 IV Abstract .. .......... 10 V Text. Chapter 1 .........e.e......... 12 Chapter 2 tee.. see..... S S S 55 Chapter 3 107 Chapter 4 ..................... 161 Chapter 5 ••SS•SSSS....SS•...SS 212 Chapter 6 SS• SSSs•• S•• SS SS S S 249 Chapter 7 eS.S....SS....S...e. -

The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing Academic Programs and Advising 2020 The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot Adam Clark Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/studentawards Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Adam, "The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot" (2020). Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing. 16. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/studentawards/16 This Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Programs and Advising at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gateway Prize for Excellent Writing by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adam Clark Victoria Malawey, Gender & Music The Riot Continues: The Problematic Westernization of Pussy Riot “We’re gonna take over the punk scene for feminists” -Kathleen Hanna Although they share feminist ideals, the Russian art collective Pussy Riot distinguishes themselves from the U.S.-based Riot Grrrl Movement, as exemplified by the band Bikini Kill, because of their location-specific protest work in Moscow. Understanding how Pussy Riot is both similar to and different from Riot Grrrl is important for contextualizing the way we think about diverse, transnational feminisms so that we may develop more inclusive and nuanced ways in conceptualizing these feminisms in the future. While Pussy Riot shares similar ideals championed by Bikini Kill in the Riot Grrrl movement, they have temporal and location-specific activisms and each group has their own ways of protesting injustices against women and achieving their unique goals. -

The “Second Quintet”: Miles Davis, the Jazz Avant-Garde, and Change, 1959-68

THE “SECOND QUINTET”: MILES DAVIS, THE JAZZ AVANT-GARDE, AND CHANGE, 1959-68 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Kwami Taín Coleman August 2014 © 2014 by Kwami T Coleman. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/vw492fh1838 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Karol Berger, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. MichaelE Veal, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Heather Hadlock I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Charles Kronengold Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost for Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. -

Universal Music Group's Profit Margins Grew in 2020, Despite

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayMARCH 3, 2021 Page 1 of 31 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Universal Music Group’s Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No.Profit 1 on Billboard’s lion audienceMargins impressions, up 16%).Grew Top• Country TuneCore Albums Unveils chart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earnedRewards 46,000 Program equivalent album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingas Indie to Nielsen Distributors Music/MRC Data. in 2020, Despiteand total Country Airplay No.Pandemic 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideFend Off marks Major Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartLabels: and fourth Exclusive top 10. It follows freshman LP BY ED CHRISTMAN Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- Montevallo, which arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He • David Crosby Sells vember 2014 and reigned for nineEven weeks. in Toa nearly date, year-long economic downturn, the hit 1.487 billionfollowed euros with ($1.68 the multiweek billion), orNo. a 1s20% “In Casemargin. -

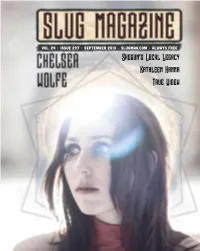

Shogun's Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow

Vol. 24 • Issue 297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com • Always Free Shogun’s Local Legacy Kathleen Hanna True Widow slugmag.com 1 2 SaltLakeUnderGround slugmag.com 3 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 24 • Issue #297 • September 2013 • slugmag.com facebook.com/SLUG.Mag @SLUGMag @SLUGMag youtube.com/user/SLUGMagazine Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Manager: Editor: Angela H. Brown Karamea Puriri Managing Editor: Esther Meroño Marketing Team: Ischa B., Sabrina Costello, Editorial Assistant: Alexander Ortega Kristina Sandi, Brooklyn Ottens, Angella Luci- Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan sano, Nicole Roccanova, Raffi Shahinian, Vic- Digital Content Coordinator: Cody Kirkland toria Loveless, Zac Freeman, Cassie Anderson, Copy Editing Team: Esther Meroño, Alexan- Cassie Loveless, Shley Kinser, Matt Brunk, Robin der Ortega, Mary E. Duncan, Cody Kirkland, Sessions, Carl Acheson, Chandler Hunt Johnathan Ford, Alex Cragun, Rachel Miller, Ka- Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer tie Bald, Liz Phillips, Allison Shephard, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Shawn Soward Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Distro: Eric Granato, Tommy Dolph, Tony Cover Designer: Joshua Joye Bassett, Nancy Burkhart, Adam Okeefe, Ryan Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Worwood, John Ford, Matt Pothier, Phil Cannon, Design Team: Eleanor Scholz, BJ Viehl, Lenny Tim Kronenberg, Justin Nelson-Carruth, Xkot Riccardi, Chad Pinckney, Mason Rodrickc Toxsik, Nancy Perkins Ad Designers: Kent Farrington, Sumerset Bivens, Christian Broadbent, Kelli Tompkins, Eric Senior Staff Writers: Mike Brown, Mariah Sapp, Brad Barker, Paden Bischoff, Maggie Mann-Mellus, James Orme, Lance Saunders, Zukowski, Thy Doan, KJ Jackett, Nicholas Dowd, Bryer Wharton, Peter Fryer, James Bennett, Ricky Nick Ketterer Vigil, Gavin Hoffman, Esther Meroño, Rebecca Website Design: Kate Colgan Vernon, Jimmy Martin, Ben Trentelman, Princess Office Interns: Carl Acheson, Robin Sessions, Kennedy, Sean Zimmerman-Wall, Cody Hudson, Alex Cragun, Chandler Hunt Shawn Mayer, Dean O. -

For the Love of It?: Zine Writing and the Study Of

FOR THE LOVE OF IT?: ZINE WRITING AND THE STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY AMATEUR WORK A Dissertation by EMILY SARA HOEFLINGER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Mary Ann O’Farrell Committee Members, Sally Robinson Giovanna Del Negro Joan Wolf Head of Department, Maura Ives May 2016 Major Subject: English Copyright 2016 Emily Sara Hoeflinger ABSTRACT In this project, I am examining zines in relation to the question of contemporary amateurism. With the onset of Web 2.0 came a space for new forms of amateur work, but this new work hasn’t been addressed as “amateur,” which has revealed a problem between what theorists know the amateur to be and what has been embraced by mainstream culture. This oversimplification of the definition of amateurism seems to threaten the integrity of amateur work in general. I analyze the concepts “transparency” and “distance” and show that both highlight the need for preserving the amateur. I confront the notion of “for the love it” by interrogating the boundaries that zine writers have established and the misperception that zine work somehow remains on the fringe of capitalist culture. Moreover, I identify the Pro Am (professional amateur) as the most significant contemporary amateur figure because it directly challenges not only what it means to be professional, but also what it means to be amateur. By examining perzines and glossies, I argue that while “for the love of it” has been downplayed or even ignored, internal rewards are still an important factor in what makes an act amateur and that external rewards don’t always have to be monetary. -

No Bitin' Allowed a Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All Of

20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 Texas Intellectual Property Law Journal Fall, 2011 Article NO BITIN’ ALLOWED: A HIP-HOP COPYING PARADIGM FOR ALL OF US Horace E. Anderson, Jr.a1 Copyright (c) 2011 Intellectual Property Law Section of the State Bar of Texas; Horace E. Anderson, Jr. I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act’s Regulation of Copying 119 II. Impact of Technology 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm 131 A. Structure 131 1. Biting 131 2. Beat Jacking 133 3. Ghosting 135 4. Quoting 136 5. Sampling 139 B. The Trademark Connection 140 C. The Authors’ Rights Connection 142 D. The New Style - What the Future of Copyright Could Look Like 143 V. Conclusion 143 VI. Appendix A 145 VII. Appendix B 157 VIII. Appendix C 163 *116 Introduction I’m not a biter, I’m a writer for myself and others. I say a B.I.G. verse, I’m only biggin’ up my brother1 It is long past time to reform the Copyright Act. The law of copyright in the United States is at one of its periodic inflection points. In the past, major technological change and major shifts in the way copyrightable works were used have rightly led to major changes in the law. The invention of the printing press prompted the first codification of copyright. The popularity of the player piano contributed to a reevaluation of how musical works should be protected.2 The dawn of the computer age led to an explicit expansion of copyrightable subject matter to include computer programs.3 These are but a few examples of past inflection points; the current one demands a similar level of change.