Michael Servetus's Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cover Page the Handle

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/20957 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Lamers, Han Title: Reinventing the ancient Greeks : the self-representation of Byzantine scholars in Renaissance Italy Issue Date: 2013-06-12 Bibliography In the bibliography, I abbreviated the following works as I cite them more than once: Boissonade Anecdota graeca e codicibus regiis, ed. Jean François Boissonade. Vol. 5. 5 vols. Paris: In regio typographeo, 1833. Lambros Νέος Ελληνομνήμων, ed. Spyridon Lambros. 21 vols. Athina: Sakellarios, 1904–1927. Legrand Bibliographie hellénique ou description raisonnée des ouvrages publiés en grec par des Grecs aux XVe et XVIe siècles, ed. Émile Legrand. 4 vols. Paris: Leroux, 1885–1906. Migne Sapientissimi Cardinalis Bessarionis Opera omnia, theologica, exegetica, polemica, partim iam edita, partim hucusque anecdota / accedunt ex virorum doctorum qui graecas litteras in Italia instaurarunt supellectili litteraria selecta quaedam, ed. Jacques Paul Migne. Patrologiae cursus completus. Series graeca 161. Lutetiae Parisiorum: Migne, 1866. Mohler Aus Bessarions Gelehrtenkreis. Abhandlungen, Reden, Briefe von Bessarion, Theodoros Gazes, Michael Apostolios, Andronikos Kallistos, Georgios Trapezuntios, Niccolò Perotti, Niccolò Capranica, ed. Ludwig Mohler. Quellen und Forschungen aus dem Gebiete der Geschichte 24. Paderborn: Schöningh, 1942. Monfasani Collectanea Trapezuntiana: Texts, documents, and biblio- graphies of George of Trebizond. Binghamton, NY: Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, 1984. Παλαιολόγεια Παλαιολόγεια καὶ Πελοποννησιακά, ed. Spyridon Lambros. 4 vols. Athina: [s.n.], 1912–1930. Sathas Μνημεῖα Ἑλληνικῆς Ἱστορίας. Monumenta Historiae Hellenicae. Documents inédits relatifs à l’histoire de la Grèce au Moyen Âge, ed. Konstantinos Sathas. Vol. 8. 9 vols. Paris: Maisonneuve, 1880. Speake Encyclopedia of Greece and the Hellenic Tradition, ed. -

This Paper Is a Descriptive Bibliography of Thirty-Three Works

Jennifer S. Clements. A Descriptive Bibliography of Selected Works Published by Robert Estienne. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. March, 2012. 48 pages. Advisor: Charles McNamara This paper is a descriptive bibliography of thirty-three works published by Robert Estienne held by the Rare Book Collection of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The paper begins with a brief overview of the Estienne Collection followed by biographical information on Robert Estienne and his impact as a printer and a scholar. The bulk of the paper is a detailed descriptive bibliography of thirty-three works published by Robert Estienne between 1527 and 1549. This bibliography includes quasi- facsimile title pages, full descriptions of the collation and pagination, descriptions of the type, binding, and provenance of the work, and citations. Headings: Descriptive Cataloging Estienne, Robert, 1503-1559--Bibliography Printing--History Rare Books A DESCRIPTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED WORKS PUBLISHED BY ROBERT ESTIENNE by Jennifer S. Clements A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina March 2012 Approved by _______________________________________ Charles McNamara 1 Table of Contents Part I Overview of the Estienne Collection……………………………………………………...2 Robert Estienne’s Press and its Output……………………………………………………2 Part II -

The Well-Trained Theologian

THE WELL-TRAINED THEOLOGIAN essential texts for retrieving classical Christian theology part 1, patristic and medieval Matthew Barrett Credo 2020 Over the last several decades, evangelicalism’s lack of roots has become conspicuous. Many years ago, I experienced this firsthand as a university student and eventually as a seminary student. Books from the past were segregated to classes in church history, while classes on hermeneutics and biblical exegesis carried on as if no one had exegeted scripture prior to the Enlightenment. Sometimes systematics suffered from the same literary amnesia. When I first entered the PhD system, eager to continue my theological quest, I was given a long list of books to read just like every other student. Looking back, I now see what I could not see at the time: out of eight pages of bibliography, you could count on one hand the books that predated the modern era. I have taught at Christian colleges and seminaries on both sides of the Atlantic for a decade now and I can say, in all honesty, not much has changed. As students begin courses and prepare for seminars, as pastors are trained for the pulpit, they are not required to engage the wisdom of the ancient past firsthand or what many have labelled classical Christianity. Such chronological snobbery, as C. S. Lewis called it, is pervasive. The consequences of such a lopsided diet are now starting to unveil themselves. Recent controversy over the Trinity, for example, has manifested our ignorance of doctrines like eternal generation, a doctrine not only basic to biblical interpretation and Christian orthodoxy for almost two centuries, but a doctrine fundamental to the church’s Christian identity. -

The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus Super Psalmos Ellen Scully Marquette University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by epublications@Marquette Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus super Psalmos Ellen Scully Marquette University Recommended Citation Scully, Ellen, "The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus super Psalmos" (2011). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 95. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/95 THE ASSUMPTION OF ALL HUMANITY IN SAINT HILARY OF POITIERS’ TRACTATUS SUPER PSALMOS by Ellen Scully A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2011 ABTRACT THE ASSUMPTION OF ALL HUMANITY IN SAINT HILARY OF POITIERS’ TRACTATUS SUPER PSALMOS Ellen Scully Marquette University, 2011 In this dissertation, I focus on the soteriological understanding of the fourth- century theologian Hilary of Poitiers as manifested in his underappreciated Tractatus super Psalmos . Hilary offers an understanding of salvation in which Christ saves humanity by assuming every single person into his body in the incarnation. My dissertation contributes to scholarship on Hilary in two ways. First, I demonstrate that Hilary’s teaching concerning Christ’s assumption of all humanity is a unique development of Latin sources. Because of his understanding of Christ’s assumption of all humanity, Hilary, along with several Greek fathers, has been accused of heterodoxy resulting from Greek Platonic influence. I demonstrate that Hilary is not influenced by Platonism; rather, though his redemption model is unique among the early Latin fathers, he derives his theology from a combination of Latin-influenced biblical exegesis and classical Roman themes. -

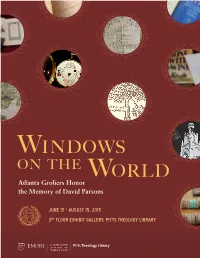

David Parsons

WINDOWS ON THE WORLD Atlanta Groliers Honor the Memory of David Parsons JUNE 15 - AUGUST 15, 2015 3RD FLOOR EXHIBIT GALLERY, PITTS THEOLOGY LIBRARY 1 WINDOWS ON THE WORLD: Atlanta Groliers Honor the Memory of David Parsons David Parsons (1939-2014) loved books, collected them with wisdom and grace, and was a noble friend of libraries. His interests were international in scope and extended from the cradle of printing to modern accounts of travel and exploration. In this exhibit of five centuries of books, maps, photographs, and manuscripts, Atlanta collectors remember their fellow Grolier Club member and celebrate his life and achievements in bibliography. Books are the windows through which the soul looks out. A home without books is like a room without windows. ~ Henry Ward Beecher CASE 1: Aurelius Victor (fourth century C.E.): On Robert Estienne and his Illustrious Men De viris illustribus (and other works). Paris: Robert Types Estienne, 25 August 1533. The small Roman typeface shown here was Garth Tissol completely new when this book was printed in The books printed by Robert Estienne (1503–1559), August, 1533. The large typeface had first appeared the scholar-printer of Paris and Geneva, are in 1530. This work, a late-antique compilation of important for the history of scholarship and learning, short biographies, was erroneously attributed to the textual history, the history of education, and younger Pliny in the sixteenth century. typography. The second quarter of the sixteenth century at Paris was a period of great innovation in Hebrew Bible the design of printing types, and Estienne’s were Biblia Hebraica. -

The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus Super Psalmos

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus super Psalmos Ellen Scully Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Scully, Ellen, "The Assumption of All Humanity in Saint Hilary of Poitiers' Tractatus super Psalmos" (2011). Dissertations (1934 -). 95. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/95 THE ASSUMPTION OF ALL HUMANITY IN SAINT HILARY OF POITIERS’ TRACTATUS SUPER PSALMOS by Ellen Scully A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2011 ABTRACT THE ASSUMPTION OF ALL HUMANITY IN SAINT HILARY OF POITIERS’ TRACTATUS SUPER PSALMOS Ellen Scully Marquette University, 2011 In this dissertation, I focus on the soteriological understanding of the fourth- century theologian Hilary of Poitiers as manifested in his underappreciated Tractatus super Psalmos . Hilary offers an understanding of salvation in which Christ saves humanity by assuming every single person into his body in the incarnation. My dissertation contributes to scholarship on Hilary in two ways. First, I demonstrate that Hilary’s teaching concerning Christ’s assumption of all humanity is a unique development of Latin sources. Because of his understanding of Christ’s assumption of all humanity, Hilary, along with several Greek fathers, has been accused of heterodoxy resulting from Greek Platonic influence. I demonstrate that Hilary is not influenced by Platonism; rather, though his redemption model is unique among the early Latin fathers, he derives his theology from a combination of Latin-influenced biblical exegesis and classical Roman themes. -

Writing World History: Which World?

Asian Review of World Histories 3:1 (January 2015), 11-35 © 2015 The Asian Association of World Historians doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12773/arwh.2015.3.1.011 Writing World History: Which World? Jean-François SALLES University Lumière Lyon 2 Lyon, France [email protected] Abstract Far from being a recent world, the concept of “a [one] world” did slowly emerged in a post-prehistoric Antiquity. The actual knowledge of the world increased through millennia leaving aside large continents (Americas, part of Africa, Australia, etc.—most areas without written history), and writing history in Antiquity cannot be a synchronal presentation of the most ancient times of these areas. Through a few case studies dealing with texts, ar- chaeology and history itself mostly in BCE times, the paper will try to perceive the slow building-up of a physical awareness and ‘mor- al’ consciousness of the known world by people of the Middle East (e.g. the Bible, Gilgamesh) and the Mediterranean (mainly Greeks). Key words the Earth, the origins of the world, drawing the world, interna- tional exchanges, Phoenicia and the Persian Gulf, Greek histori- ans, Greek geographers Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 06:34:40PM via free access 12 | ASIAN REVIEW OF WORLD HISTORIES 3:1 (JANUARY 2015) I. INTRODUCTION Investigating how to write a “World History” in its most ancient periods—leaving aside Prehistory to the benefit of times when written sources are available—would require to coalesce togeth- er several disciplines, geography and historiography indeed but also linguistics—there is real problem of vocabulary— philosophy, theology, etc. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 04 April 2018 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: O'Brien, John (2015) 'A book (or two) from the Library of La Bo¡etie.',Montaigne studies., 27 (1-2). pp. 179-191. Further information on publisher's website: https://classiques-garnier.com/montaigne-studies-2015-an-interdisciplinary-forum-n-27-montaigne-and-the-art- of-writing-a-book-or-two-from-the-library-of-la-boetie.html Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk A Book (or Two) from the Library of La Boétie John O’Brien The copy of the Greek editio princeps of Cassius Dio, now in Eton College, has long been recognized as formerly belonging to Montaigne (figure 1).1 It bears his signature in the usual place and in his usual style. -

Lordship in Ninth-Century Francia: the Case of Bishop Hincmar of Laon and His Followers

This is a repository copy of Lordship in Ninth-Century Francia: The Case of Bishop Hincmar of Laon and his Followers. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/87260/ Version: Accepted Version Article: West, C. (2015) Lordship in Ninth-Century Francia: The Case of Bishop Hincmar of Laon and his Followers. Past and Present, 226. 3 - 40. ISSN 1477-464X https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtu044 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in Past and Present following peer review. The version of record West, C. (2015) Lordship in Ninth-Century Francia: The Case of Bishop Hincmar of Laon and his Followers. Past and Present, 226. 3 - 40 is available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtu044 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. -

Und Des »Gnomon Online« Regensburger Systematik Notation

Der Thesaurus der »Gnomon Bibliographischen Datenbank« und des »Gnomon Online« Regensburger Systematik Notation AX Notation BB Notation BC Notation BD Notation BO Notation CC Notation CD Notation FB Notation FC Notation FD Notation FE Notation FF Notation FH Notation FP Notation FQ Notation FR Notation FS Notation FT Notation FX Notation LE Notation LF Notation LG Notation LH Notation NB Notation NC Notation ND Notation NF Notation NG Notation NH Notation NK Notation NM Notation PV Dissertationen (Sign. 23) Verwaltungsdeskriptoren Bestand der UB Eichstätt Ausstellungskatalog Bibliographica Festschrift Forschungsbericht Gesammelte Schriften, Aufsatzsammlung Kartenwerk Kongreß Lexikon Quellensammlungen Rezensionen Sammelwerke Sammelwerke, Gesamttitel ANRW Cambridge Ancient History Cambridge History of Iran Cambridge History of Judaism Der Kleine Pauly Der Neue Pauly Éntretiens sur l'Antiquité Classique Lexikon der Alten Welt Lexikon des Mittelalters LIMC Neue Deutsche Biographie OCD (Second Edition) OCD (Third Edition) Pauly-Wissowa (RE) RAC RGG Wege der Forschung Zeitschriften Acme ACOR newsletter Acta ad archaeologiam ... pertinentia Acta Antiqua Hungarica Acta Classica Acta Hyperborea Aegyptus Aevum antiquum Aevum. Rassegna di Scienze storiche Afghan Studies Agora (Eichstätt) Akroterion Alba Regia American Historical Review American Journal of Ancient History American Journal of Archaeology American Journal of Numismatics American Journal of Philology American Numismatic Society American Scholar Analecta Romana Instituti Danici Anales -

Thesaurus Systématique 2007

Banco de datos bibliograficos Gnomon Tesauro sistematico Auctores Acacius theol. TLG 2064 Accius trag. Achilles Tatius astron. TLG 2133 Achilles Tatius TLG 0532 Achmet onir. C. Acilius phil. et hist. TLG 2545 (FGrHist 813) Acta Martyrum Alexandrinorum TLG 0300 Acta Thomae TLG 2038 Acusilaus hist. TLG 0392 (FGrHist 2) Adamantius med. TLG 0731 Adrianus soph. TLG 0666 Aegritudo Perdicae Aelianus soph. TLG 545 Aelianus tact. TLG 0546 Aelius Promotus med. TLG 0674 Aelius Stilo Aelius Theon rhet. TLG 0607 Aemilianus rhet. TLG 0103 Aemilius Asper Aemilius Macer Aemilius Scaurus cos. 115 Aeneas Gazaeus TLG 4001 Aeneas Tacticus TLG 0058 Aenesidemus hist. TLG 2413 (FGrHist 600) Aenesidemus phil. Aenigmata Aeschines orator TLG 0026 Aeschines rhet. TLG 0104 Aeschines Socraticus TLG 0673 Aeschrion lyr. TLG 0679 Aeschylus trag. TLG 0085 Aeschyli Fragmenta Aeschyli Oresteia Aeschyli Agamemnon Aeschyli Choephori Aeschyli Eumenides Aeschyli Persae Aeschyli Prometheus vinctus Aeschyli Septem contra Thebas Aeschyli Supplices Aesopica TLG 0096 Aetheriae Peregrinatio Aethicus Aethiopis TLG 0683 Aetius Amidenus med. TLG 0718 Aetius Doxographus TLG 0528 Banco de datos bibliograficos Gnomon La busqueda de un descriptor en español dentro de la busqueda de texto completo corresponde a la misma de un descriptor en aleman y conduce al mismo resultado Versión 2009 Pagina 1 Banco de datos bibliograficos Gnomon Tesauro sistematico Aetna carmen Afranius Africanus, Sextus Iulius Agapetus TLG 0761 Agatharchides geogr. TLG 0067 (FGrHist 86) Agathemerus geogr. TLG 0090 Agathias Scholasticus TLG 4024 Agathocles gramm. TLG 4248 Agathocles hist. TLG 2534 (FGrHist 799) Agathon hist. TLG 2566 (FGrHist 843) Agathon trag. TLG 0318 Agathyllus eleg. TLG 2606 Agnellus scr. -

2003 Calvin Bibliography

2003 Calvin Bibliography Compiled by Paul Fields I. Calvin’s Life and Times A. Biography B. Cultural ContextIntellectual History C. Cultural ContextSocial History D. Friends and Associates E. Polemical Relationships II. Calvin’s Works A. Works and Selections B. Critique III. Calvin’s Theology A. Overview B. Doctrine of God 1. Knowledge of God 2 . Providence 3. Sovereignty 4. Trinity C. Doctrine of Christ D. Doctrine of the Holy Spirit E. Doctrine of Salvation 1. Assurance 2. Justification 3. Predestination F. Doctrine of Humanity 1. Image of God 2. Natural Law 3. Sin G. Doctrine of the Christian Life 1. Ethics 2. Piety 3. Sanctification H. Ecclesiology 1. Overview 2. Discipline and Instruction 3. Missions 4. Polity I. Worship 1. Iconoclasm 2. Liturgy 3. Music 4. Prayer 5. Preaching and Sacraments J. Revelation 1. Exegesis and Hermeneutics 2. Scripture K. Apocalypticism L. Patristic and Medieval Influences M. Method IV. Calvin and SocialEthical Issues V. Calvin and Political Issues VI. Calvinism A. Theological Influence 1. Overview 2. Christian Life 3. Covenants 4. Discipline 5. Dogmatics 6. Ecclesiology 7. Education 8. Grace 9. God 10. Justification 11. Predestination 12. Revelation 13. Sacraments 14. Salvation 15. Worship B. Cultural Influence 1. Overview 2. Literature C. Social, Economic, and Political Influence D. International Influence 1. England 2. France 3. Germany 4. Hungary 5. Netherlands 6. South Africa 7. Transylvania 8. United States E. Critique VII. Book Reviews I. Calvin’s Life and Times A. Biography Brockington, William S., Jr. "John Calvin." In Dictionary of World Biography, Vol. 3: The Renaissance, edited by Frank N.