Writing World History: Which World?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CILICIA: the FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES in ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson

CILICIA: THE FIRST CHRISTIAN CHURCHES IN ANATOLIA1 Mark Wilson Summary This article explores the origin of the Christian church in Anatolia. While individual believers undoubtedly entered Anatolia during the 30s after the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:9–10), the book of Acts suggests that it was not until the following decade that the first church was organized. For it was at Antioch, the capital of the Roman province of Syria, that the first Christians appeared (Acts 11:20–26). Yet two obscure references in Acts point to the organization of churches in Cilicia at an earlier date. Among the addressees of the letter drafted by the Jerusalem council were the churches in Cilicia (Acts 15:23). Later Paul visited these same churches at the beginning of his second ministry journey (Acts 15:41). Paul’s relationship to these churches points to this apostle as their founder. Since his home was the Cilician city of Tarsus, to which he returned after his conversion (Gal. 1:21; Acts 9:30), Paul was apparently active in church planting during his so-called ‘silent years’. The core of these churches undoubtedly consisted of Diaspora Jews who, like Paul’s family, lived in the region. Jews from Cilicia were members of a Synagogue of the Freedmen in Jerusalem, to which Paul was associated during his time in Jerusalem (Acts 6:9). Antiochus IV (175–164 BC) hellenized and urbanized Cilicia during his reign; the Romans around 39 BC added Cilicia Pedias to the province of Syria. Four cities along with Tarsus, located along or near the Pilgrim Road that transects Anatolia, constitute the most likely sites for the Cilician churches. -

Greek Cities & Islands of Asia Minor

MASTER NEGATIVE NO. 93-81605- Y MICROFILMED 1 993 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES/NEW YORK / as part of the "Foundations of Western Civilization Preservation Project'' Funded by the NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES Reproductions may not be made without permission from Columbia University Library COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The copyright law of the United States - Title 17, United photocopies or States Code - concerns the making of other reproductions of copyrighted material. and Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries or other archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy the reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that for any photocopy or other reproduction is not to be "used purpose other than private study, scholarship, or for, or later uses, a research." If a user makes a request photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of fair infringement. use," that user may be liable for copyright a This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept fulfillment of the order copy order if, in its judgement, would involve violation of the copyright law. AUTHOR: VAUX, WILLIAM SANDYS WRIGHT TITLE: GREEK CITIES ISLANDS OF ASIA MINOR PLACE: LONDON DA TE: 1877 ' Master Negative # COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES PRESERVATION DEPARTMENT BIBLIOGRAPHIC MTCROFORM TAR^FT Original Material as Filmed - Existing Bibliographic Record m^m i» 884.7 !! V46 Vaux, V7aiion Sandys Wright, 1818-1885. ' Ancient history from the monuments. Greek cities I i and islands of Asia Minor, by W. S. W. Vaux... ' ,' London, Society for promoting Christian knowledce." ! 1877. 188. p. plate illus. 17 cm. ^iH2n KJ Restrictions on Use: TECHNICAL MICROFORM DATA i? FILM SIZE: 3 S'^y^/"^ REDUCTION IMAGE RATIO: J^/ PLACEMENT: lA UA) iB . -

La Piraterie Dans La Méditerranée Antique : Représentations Et Insertion Dans Les Structures Économiques Tome 1

La piraterie dans la M´editerran´eeantique : repr´esentations et insertion dans les structures ´economiques Cl´ement Varenne To cite this version: Cl´ement Varenne. La piraterie dans la M´editerran´eeantique : repr´esentations et insertion dans les structures ´economiques.Arch´eologie et Pr´ehistoire.Universit´eToulouse le Mirail - Toulouse II, 2013. Fran¸cais. <NNT : 2013TOU20048>. <tel-00936571> HAL Id: tel-00936571 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00936571 Submitted on 27 Jan 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. 5)µ4& &OWVFEFMPCUFOUJPOEV %0$503"5%&-6/*7&34*5²%&506-064& %ÏMJWSÏQBS Université Toulouse 2 Le Mirail (UT2 Le Mirail) 1SÏTFOUÏFFUTPVUFOVFQBS Clément VARENNE le 29 juin 2013 5JUSF La piraterie dans la Méditerranée antique : représentations et insertion dans les structures économiques Tome 1 ²DPMFEPDUPSBMF et discipline ou spécialité ED TESC : Sciences de l'Antiquité 6OJUÏEFSFDIFSDIF TRACES UMR 5608 %JSFDUFVS T EFʾÒTF M. Pierre MORET, CNRS Jury: M. Nicholas PURCELL, Professeur Université d'Oxford (rapporteur) M. Christophe PÉBARTHE, MCF Université Bordeaux 3 (rapporteur) M. Jean Marie PAILLER, Professeur Université Toulouse-Le Mirail 1 En mémoire de Romain Poussard 2 Remerciements Mes travaux de recherche ont été réalisés au sein du laboratoire TRACES UMR 5608. -

Journey to Antioch, However, I Would Never Have Believed Such a Thing

Email me with your comments! Table of Contents (Click on the Title) Prologue The Gentile Heart iv Part I The Road North 1 Chapter One The Galilean Fort 2 Chapter Two On the Trail 14 Chapter Three The First Camp 27 Chapter Four Romans Versus Auxilia 37 Chapter Five The Imperial Way Station 48 Chapter Six Around the Campfire 54 Chapter Seven The Lucid Dream 63 Chapter Eight The Reluctant Hero 68 Chapter Nine The Falling Sickness 74 Chapter Ten Stopover In Tyre 82 Part II Dangerous Passage 97 Chapter Eleven Sudden Detour 98 Chapter Twelve Desert Attack 101 Chapter Thirteen The First Oasis 111 Chapter Fourteen The Men in Black 116 Chapter Fifteen The Second Oasis 121 Chapter Sixteen The Men in White 128 Chapter Seventeen Voice in the Desert 132 Chapter Eighteen Dark Domain 136 Chapter Nineteen One Last Battle 145 Chapter Twenty Bandits’ Booty 149 i Chapter Twenty-One Journey to Ecbatana 155 Chapter Twenty-Two The Nomad Mind 162 Chapter Twenty-Three The Slave Auction 165 Part III A New Beginning 180 Chapter Twenty-Four A Vision of Home 181 Chapter Twenty-Five Journey to Tarsus 189 Chapter Twenty-Six Young Saul 195 Chapter Twenty-Seven Fallen from Grace 210 Chapter Twenty-Eight The Roman Escorts 219 Chapter Twenty-Nine The Imperial Fort 229 Chapter Thirty Aurelian 238 Chapter Thirty-One Farewell to Antioch 246 Part IV The Road Home 250 Chapter Thirty-Two Reminiscence 251 Chapter Thirty-Three The Coastal Route 259 Chapter Thirty-Four Return to Nazareth 271 Chapter Thirty-Five Back to Normal 290 Chapter Thirty-Six Tabitha 294 Chapter Thirty-Seven Samuel’s Homecoming Feast 298 Chapter Thirty-Eight The Return of Uriah 306 Chapter Thirty-Nine The Bosom of Abraham 312 Chapter Forty The Call 318 Chapter Forty-One Another Adventure 323 Chapter Forty-Two Who is Jesus? 330 ii Prologue The Gentile Heart When Jesus commissioned me to learn the heart of the Gentiles, he was making the best of a bad situation. -

Und Des »Gnomon Online« Regensburger Systematik Notation

Der Thesaurus der »Gnomon Bibliographischen Datenbank« und des »Gnomon Online« Regensburger Systematik Notation AX Notation BB Notation BC Notation BD Notation BO Notation CC Notation CD Notation FB Notation FC Notation FD Notation FE Notation FF Notation FH Notation FP Notation FQ Notation FR Notation FS Notation FT Notation FX Notation LE Notation LF Notation LG Notation LH Notation NB Notation NC Notation ND Notation NF Notation NG Notation NH Notation NK Notation NM Notation PV Dissertationen (Sign. 23) Verwaltungsdeskriptoren Bestand der UB Eichstätt Ausstellungskatalog Bibliographica Festschrift Forschungsbericht Gesammelte Schriften, Aufsatzsammlung Kartenwerk Kongreß Lexikon Quellensammlungen Rezensionen Sammelwerke Sammelwerke, Gesamttitel ANRW Cambridge Ancient History Cambridge History of Iran Cambridge History of Judaism Der Kleine Pauly Der Neue Pauly Éntretiens sur l'Antiquité Classique Lexikon der Alten Welt Lexikon des Mittelalters LIMC Neue Deutsche Biographie OCD (Second Edition) OCD (Third Edition) Pauly-Wissowa (RE) RAC RGG Wege der Forschung Zeitschriften Acme ACOR newsletter Acta ad archaeologiam ... pertinentia Acta Antiqua Hungarica Acta Classica Acta Hyperborea Aegyptus Aevum antiquum Aevum. Rassegna di Scienze storiche Afghan Studies Agora (Eichstätt) Akroterion Alba Regia American Historical Review American Journal of Ancient History American Journal of Archaeology American Journal of Numismatics American Journal of Philology American Numismatic Society American Scholar Analecta Romana Instituti Danici Anales -

Thesaurus Systématique 2007

Banco de datos bibliograficos Gnomon Tesauro sistematico Auctores Acacius theol. TLG 2064 Accius trag. Achilles Tatius astron. TLG 2133 Achilles Tatius TLG 0532 Achmet onir. C. Acilius phil. et hist. TLG 2545 (FGrHist 813) Acta Martyrum Alexandrinorum TLG 0300 Acta Thomae TLG 2038 Acusilaus hist. TLG 0392 (FGrHist 2) Adamantius med. TLG 0731 Adrianus soph. TLG 0666 Aegritudo Perdicae Aelianus soph. TLG 545 Aelianus tact. TLG 0546 Aelius Promotus med. TLG 0674 Aelius Stilo Aelius Theon rhet. TLG 0607 Aemilianus rhet. TLG 0103 Aemilius Asper Aemilius Macer Aemilius Scaurus cos. 115 Aeneas Gazaeus TLG 4001 Aeneas Tacticus TLG 0058 Aenesidemus hist. TLG 2413 (FGrHist 600) Aenesidemus phil. Aenigmata Aeschines orator TLG 0026 Aeschines rhet. TLG 0104 Aeschines Socraticus TLG 0673 Aeschrion lyr. TLG 0679 Aeschylus trag. TLG 0085 Aeschyli Fragmenta Aeschyli Oresteia Aeschyli Agamemnon Aeschyli Choephori Aeschyli Eumenides Aeschyli Persae Aeschyli Prometheus vinctus Aeschyli Septem contra Thebas Aeschyli Supplices Aesopica TLG 0096 Aetheriae Peregrinatio Aethicus Aethiopis TLG 0683 Aetius Amidenus med. TLG 0718 Aetius Doxographus TLG 0528 Banco de datos bibliograficos Gnomon La busqueda de un descriptor en español dentro de la busqueda de texto completo corresponde a la misma de un descriptor en aleman y conduce al mismo resultado Versión 2009 Pagina 1 Banco de datos bibliograficos Gnomon Tesauro sistematico Aetna carmen Afranius Africanus, Sextus Iulius Agapetus TLG 0761 Agatharchides geogr. TLG 0067 (FGrHist 86) Agathemerus geogr. TLG 0090 Agathias Scholasticus TLG 4024 Agathocles gramm. TLG 4248 Agathocles hist. TLG 2534 (FGrHist 799) Agathon hist. TLG 2566 (FGrHist 843) Agathon trag. TLG 0318 Agathyllus eleg. TLG 2606 Agnellus scr. -

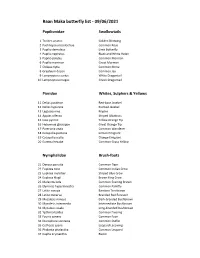

Baan Maka Butterfly List - 09/06/2021

Baan Maka butterfly list - 09/06/2021 Papilionidae Swallowtails 1 Troides aeacus Golden Birdwing 2 Pachliopta aristolochiae Common Rose 3 Papilio demoleus Lime Butterfly 4 Papilio nephelus Black and White Helen 5 Papilio polytes Common Mormon 6 Papilio memnon Great Mormon 7 Chilasa clytia Common Mime 8 Graphium doson Common Jay 9 Lamproptera curius White Dragontail 10 Lamproptera meges Green Dragontail Pieridae Whites, Sulphers & Yellows 11 Delias pasithoe Red-base Jezebel 12 Delias hyparete Painted Jezebel 13 Leptosia nina Psyche 14 Appias olferna Striped Albatross 15 Ixias pyrene Yellow Orange Tip 16 Hebomoia glaucippe Great Orange Tip 17 Pareronia anais Common Wanderer 18 Catopsilia pomona Lemon Emigrant 19 Catopsilia scylla Orange Emigrant 20 Eurema hecabe Common Grass Yellow Nymphalidae Brush-foots 21 Danaus genutia Common Tiger 22 Euploea core Common Indian Crow 23 Euploea mulciber Striped Blue Crow 24 Euploea klugii Brown King Crow 25 Melanitis leda Common Evening Brown 26 Elymnias hypermnestra Common Palmfly 27 Lethe europa Bamboo Treebrown 28 Lethe minerva Branded Red Forester 29 Mycalesis mineus Dark-branded Bushbrown 30 Mycalesis intermedia Intermediate Bushbrown 31 Mycalesis visala Long-branded Bushbrown 32 Ypthima baldus Common Fivering 33 Faunis canens Common Faun 34 Discophora sondaica Common Duffer 35 Cethosia cyane Leopard Lacewing 36 Phalanta phalantha Common Leopard 37 Cupha erymanthis Rustic 38 Vagrans sinha Vagrant 39 Cirrochroa tyche Common Yeoman 40 Terinos clarissa Malayan Assyrian 41 Junonia iphita Chocolate Pansy -

About Rivers and Mountains and Things Found in Them Pp

PSEUDO-PLUTARCH ABOUT RIVERS AND MOUNTAINS AND THINGS FOUND IN THEM Translated by Thomas M. Banchich With Sarah Brill, Emilyn Haremza, Dustin Hummel, and Ryan Post Canisius College Translated Texts, Number 4 Canisius College, Buffalo, New York 2010 i CONTENTS Acknowledgements p. ii Introduction pp. iii-v Pseudo-Plutarch, About Rivers and Mountains and Things Found in Them pp. 1-24 Indices pp. 24-32 Canisius College Translated Texts p. 33 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The cover image is Jean-Antoine Gros’s 1801 painting “Sappho at Leucate,” now at the Musée Baron Gérard, Bayeux (http://www.all-art.org/neoclasscism/gros1.html, accessed June 10, 2010). Though Pseudo-Plutarch has men alone, not women (who choose the noose), fling themselves from precipices, the despair that supposedly drove Sappho to leap to her death from Mt. Leucate is a leitmotif of About Rivers and Mountains and Things Found in Them. Thanks are due to Andrew Banchich and Christopher Filkins for their assistance with a range of technical matters and to Ryan Post, who read and commented on drafts of the translation. ii INTRODUCTION In the spring of 2007, I suggested to four students—Sarah Brill, Emilyn Haremza, Dustin Hummel, and Ryan Post—the preparation of an English translation of ΠΕΡΙ ΠΟΤΑΜΩΝ ΚΑΙ ΟΡΩΝ ΕΠΩΝΥΜΙΑΣ ΚΑΙ ΤΩΝ ΕΝ ΑΥΤΟΙΣ ΕΥΡΙΣΚΟΜΕΝΩΝ, better known, when known at all, by its abbreviated Latin title, De fluviis, About Rivers. Their resultant rough version of a portion of About Rivers, in turn, provided the impetus for the translation presented here. However, while the students worked from Estéban Calderón Dorda’s text in the Corpus Plutarchi Moralium series, for reasons of copyright, I have employed what was the standard edition prior to Dorda’s, that of Rudolph Hercher.1 Only the ninth-century codex Palatinus gr. -

ATLAS of CLASSICAL HISTORY

ATLAS of CLASSICAL HISTORY EDITED BY RICHARD J.A.TALBERT London and New York First published 1985 by Croom Helm Ltd Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. © 1985 Richard J.A.Talbert and contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Atlas of classical history. 1. History, Ancient—Maps I. Talbert, Richard J.A. 911.3 G3201.S2 ISBN 0-203-40535-8 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-71359-1 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-03463-9 (pbk) Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Also available CONTENTS Preface v Northern Greece, Macedonia and Thrace 32 Contributors vi The Eastern Aegean and the Asia Minor Equivalent Measurements vi Hinterland 33 Attica 34–5, 181 Maps: map and text page reference placed first, Classical Athens 35–6, 181 further reading reference second Roman Athens 35–6, 181 Halicarnassus 36, 181 The Mediterranean World: Physical 1 Miletus 37, 181 The Aegean in the Bronze Age 2–5, 179 Priene 37, 181 Troy 3, 179 Greek Sicily 38–9, 181 Knossos 3, 179 Syracuse 39, 181 Minoan Crete 4–5, 179 Akragas 40, 181 Mycenae 5, 179 Cyrene 40, 182 Mycenaean Greece 4–6, 179 Olympia 41, 182 Mainland Greece in the Homeric Poems 7–8, Greek Dialects c. -

Baan Maka Butterfly List - 24/06/2019

Baan Maka butterfly list - 24/06/2019 Swallowtails 1 Troides aeacus Golden Birdwing 2 Papilio nephelus Black and White Helen 3 Papilio polytes Common Mormon 4 Papilio memnon Great Mormon 5 Lamproptera curius White Dragontail 6 Lamproptera meges Green Dragontail Whites, Sulphers & Yellows 7 Delias pasithoe Red-base Jezebel 8 Delias hyparete Painted Jezebel 9 Leptosia nina Psyche 10 Appias olferna Striped Albatross 11 Ixias pyrene Yellow Orange Tip 12 Hebomoia glaucippe Great Orange Tip 13 Pareronia anais Common Wanderer 14 Catopsilia pomona Lemon Emigrant 15 Catopsilia scylla Orange Emigrant 16 Eurema hecabe Common Grass Yellow Brush-foots 17 Euploea core Common Indian Crow 18 Euploea mulciber Striped Blue Crow 19 Melanitis leda Common Evening Brown 20 Elymnias hypermnestra Common Palmfly 21 Lethe europa Bamboo Treebrown 22 Lethe minerva Branded Red Forester 23 Mycalesis mineus Dark-branded Bushbrown 24 Mycalesis intermedia Intermediate Bushbrown 25 Mycalesis visala Long-branded Bushbrown 26 Ypthima baldus Common Fivering 27 Faunis canens Common Faun 28 Discophora sondaica Common Duffer 29 Cupha erymanthis Rustic 30 Vagrans sinha Vagrant 31 Cirrochroa tyche Common Yeoman 32 Terinos clarissa Malayan Assyrian 33 Junonia iphita Chocolate Pansy 34 Junonia almana Peacock Pansy 35 Junonia lemonias Lemon Pansy 36 Hypolimnas bolina Great Eggfly 37 Cyrestis themire Little Map 38 Cyrestis cocles Marbled Map 39 Neptis nata Sullied Brown Sailor 40 Neptis miah Small Yellow Sailor 41 Lasippa heliodore Burmese Lascar 42 Pantoporia hordonia Common Lascar -

Settlement, Urbanization, and Population

OXFORD STUDIES ON THE ROMAN ECONOMY General Editors Alan Bowman Andrew Wilson OXFORD STUDIES ON THE ROMAN ECONOMY This innovative monograph series reflects a vigorous revival of inter- est in the ancient economy, focusing on the Mediterranean world under Roman rule (c. 100 bc to ad 350). Carefully quantified archaeological and documentary data will be integrated to help ancient historians, economic historians, and archaeologists think about economic behaviour collectively rather than from separate perspectives. The volumes will include a substantial comparative element and thus be of interest to historians of other periods and places. Settlement, Urbanization, and Population Edited by ALAN BOWMAN and ANDREW WILSON 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Oxford University Press 2011 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

Geografia E Cartografia Dell'estremo Occidente Da Eratostene a Tolemeo

GEOGRAFIA E CARTOGRAFIA DELL’ESTREMO OCCIDENTE DA ERATOSTENE A TOLEMEO Serena Bianchetti Università di Firenze RIASSUNTO: La concezione geografica dell’estremo Occidente e la rappresentazione cartografica di questa area variano in relazione alla storia politica dei Greci e dei Romani che occuparono le aree mediterranee della Spagna e quelle atlantiche: i racconti dei navigatori confluiti nelle ricostruzioni degli storici aiutano solo in parte a ricostru- ire le effettive conoscenze dei luoghi perché Ecateo, Erodoto e lo stesso Polibio «piegano» i dati in funzione della loro idea dell’ecumene. Solo la ricerca scientifica di Eudosso, Pitea, Eratostene e Tolemeo cerca di spiegare il mondo con le leggi della ge- ometria e disegna l’ecumene mediante una griglia di coordinate astronomiche. La ricerca di Eratostene e in parti- colare quella sulle aree estreme dell’Occidente e del Nord costituisce il contributo più innovativo e più criticato da parte dei successori: Polibio e Artemidoro, seguiti in parte da Strabone, combattono l’idea eratostenica del mondo e contribuiscono alla sfortuna della geografia scientifica. Sarà Tolemeo a riprendere la concezione matematica di Eratostene: l’analisi dei passi della Geografia e i confronti con Marciano, aiutano a comprendere infatti lo stretto rapporto che unisce Tolemo ai geografi scienziati dei quali è l’ultimo rappresentante. PAROLE CHIAVE: Estremo Occidente. Geografia storica. Geografia scientifica. Cartografia. GEOGRAPHY AND CARTOGRAPHY FROM THE FAR WEST OF ERATOSTHENES TO PTOLEMAIOS ABSTRACT: The geographical concept of the Far West and its mapping vary in accordance with the political history of Ancient Greeks and Romans, who occupied the Spanish Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts. Historians’ views based upon sailors’ accounts only partly contribute to the mapping of this area of the oikoumene.