Ceramics Monthly Nov90 Cei11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Impact Report

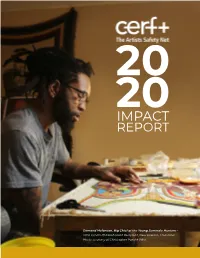

20 20 IMPACT REPORT Demond Melancon, Big Chief of the Young Seminole Hunters – 2020 COVID-19 Relief Grant Recipient, New Orleans, Louisiana, Photo courtesy of Christopher Porché West OUR MISSION A Letter from CERF+ Plan + Pivot + Partner CERF+’s mission is to serve artists who work in craft disciplines by providing a safety In the first two decades of the 21st century,CERF+ ’s safety net of services gradually net to support strong and sustainable careers. CERF+’s core services are education expanded to better meet artists’ needs in response to a series of unprecedented natural programs, resources on readiness, response and recovery, advocacy, network building, disasters. The tragic events of this past year — the pandemic, another spate of catastrophic and emergency relief assistance. natural disasters, as well as the societal emergency of racial injustice — have thrust us into a new era in which we have had to rethink our work. Paramount in this moment has been BOARD OF DIRECTORS expanding our definition of “emergency” and how we respond to artists in crises. Tanya Aguiñiga Don Friedlich Reed McMillan, Past Chair While we were able to sustain our longstanding relief services, we also faced new realities, which required different actions. Drawing from the lessons we learned from administering Jono Anzalone, Vice Chair John Haworth* Perry Price, Treasurer aid programs during and after major emergencies in the previous two decades, we knew Malene Barnett Cinda Holt, Chair Paul Sacaridiz that our efforts would entail both a sprint and a marathon, requiring us to plan, pivot, Barry Bergey Ande Maricich* Jaime Suárez and partner. -

Gareth Mason: the Attraction of Opposites Focus the Culture of Clay

focus MONTHLY the culture of clay of culture the Gareth Mason: The Attraction of Opposites focus the culture of clay NOVEMBER 2008 $7.50 (Can$9) www.ceramicsmonthly.org Ceramics Monthly November 2008 1 MONTHLY Publisher Charles Spahr Editorial The [email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5895 fax: (614) 891-8960 editor Sherman Hall assistant editor Brandy Wolfe Ceramic assistant editor Jessica Knapp technical editor Dave Finkelnburg online editor Jennifer Poellot Harnetty editorial assistant Holly Goring Advertising/Classifieds Arts [email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5834 fax: (614) 891-8960 classifi[email protected] telephone: (614) 794-5843 advertising manager Mona Thiel Handbook Only advertising services Jan Moloney Marketing telephone: (614) 794-5809 marketing manager Steve Hecker Series $29.95 each Subscriptions/Circulation customer service: (800) 342-3594 [email protected] Design/Production Electric Firing: Glazes & Glazing: production editor Cynthia Griffith design Paula John Creative Techniques Finishing Techniques Editorial and advertising offices 600 Cleveland Ave., Suite 210 Westerville, Ohio 43082 Editorial Advisory Board Linda Arbuckle; Professor, Ceramics, Univ. of Florida Scott Bennett; Sculptor, Birmingham, Alabama Tom Coleman; Studio Potter, Nevada Val Cushing; Studio Potter, New York Dick Lehman; Studio Potter, Indiana Meira Mathison; Director, Metchosin Art School, Canada Bernard Pucker; Director, Pucker Gallery, Boston Phil Rogers; Potter and Author, Wales Jan Schachter; Potter, California Mark Shapiro; Worthington, Massachusetts Susan York; Santa Fe, New Mexico Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is published monthly, except July and August, by Ceramic Publications Company; a Surface Decoration: Extruder, Mold & Tile: subsidiary of The American Ceramic Society, 600 Cleveland Ave., Suite 210, Westerville, Ohio 43082; www.ceramics.org. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

Pueblo Grande Museum ‐ Partial Library Catalog

Pueblo Grande Museum ‐ Partial Library Catalog ‐ Sorted by Title Book Title Author Additional Author Publisher Date 100 Questions, 500 Nations: A Reporter's Guide to Native America Thames, ed., Rick Native American Journalists Association 1998 11,000 Years on the Tonto National Forest: Prehistory and History in Wood, J. Scott McAllister, et al., Marin E. Southwest Natural and Cultural Heritage 1989 Central Arizona Association 1500 Years of Irrigation History Halseth, Odd S prepared for the National Reclamation 1947 Association 1936‐1937 CCC Excavations of the Pueblo Grande Platform Mound Downum, Christian E. 1991 1970 Summer Excavation at Pueblo Grande, Phoenix, Arizona Lintz, Christopher R. Simonis, Donald E. 1970 1971 Summer Excavation at Pueblo Grande, Phoenix, Arizona Fliss, Brian H. Zeligs, Betsy R. 1971 1972 Excavations at Pueblo Grande AZ U:9:1 (PGM) Burton, Robert J. Shrock, et. al., Marie 1972 1974 Cultural Resource Management Conference: Federal Center, Denver, Lipe, William D. Lindsay, Alexander J. Northern Arizona Society of Science and Art, 1974 Colorado Inc. 1974 Excavation of Tijeras Pueblo, Tijeras Pueblo, Cibola National Forest, Cordell, Linda S. U. S.DA Forest Service 1975 New Mexico 1991 NAI Workshop Proceedings Koopmann, Richard W. Caldwell, Doug National Association for Interpretation 1991 2000 Years of Settlement in the Tonto Basin: Overview and Synthesis of Clark, Jeffery J. Vint, James M. Center for Desert Archaeology 2004 the Tonto Creek Archaeological Project 2004 Agave Roast Pueblo Grande Museum Pueblo Grande Museum 2004 3,000 Years of Prehistory at the Red Beach Site CA‐SDI‐811 Marine Corps Rasmussen, Karen Science Applications International 1998 Base, Camp Pendleton, California Corporation 60 Years of Southwestern Archaeology: A History of the Pecos Conference Woodbury, Richard B. -

Ceramics Monthly Sep92 Cei09

mm William Hunt................................ Editor Ruth C. Butler..................Associate Editor Robert L. Creager.................Art Director Kim S. Nagorski...............Assistant Editor Mary Rushley...........Circulation Manager Mary E. Beaver......... Circulation Assistant Connie Belcher..........Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis....................... Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Profes sional Publications, Inc., 1609 Northwest Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address: Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to:Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustrations, announce ments and news releases about ceramics are wel come and will be considered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated materials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines: A book let describing standards and procedures for sub mitting materials is available upon request. Indexing: An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Additionally,Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in theArt Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) in dexing is available through Wilsonline, 950 University Ave., Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Co., 362 Lakeside Dr., Forest City, California 94404. -

Susan Harnly Peterson Papers

ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY ART MUSEUM CERAMICS RESEARCH CENTER SUSAN HARNLY PETERSON PAPERS July 2010 (updated January 2015) Contact Information Arizona State University Art Museum Ceramics Research Center P.O. Box 872911 Tempe, AZ 85287-2911 http://asuartmuseum.asu.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS Collection Overview 2 Administrative Information 2 Biographical Note 3 Scope and Content Note 3 Arrangement 4 Series Descriptions/Container Listing Series 1: Media Box 1: Miscellaneous Films and Tapes 5 Box 2: Miscellaneous Films and Tapes; Hamada film 6 Box 3: Miscellaneous Slides 7 Box 4: Audio Material 20 Series 2: Books on Ceramics Box 5: Book: The Craft and Art of Clay, 1st edition 25 Box 6: Book: The Craft and Art of Clay, 1st edition (1992) 25 Box 7: Book: The Craft and Art of Clay, 1st edition (1992) 25 Box 8: Book: The Craft and Art of Clay, 1st edition (1992) 26 Box 9: Book: The Craft and Art of Clay, 2nd edition (1996) 27 Box 10: Books: The Craft and Art of Clay, 3rd and 4th editions 28 (2000 and 2003) Box 11: Materials and Drafts of Books (Contemporary Ceramics, 28 Smashing Glazes, Working with Clay) and Television Show (“Wheels, Kilns & Clay”) Box 12: Book: Pottery of American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations 29 Series 3: Books on Individual Artists Box 13: Book: Lucy Lewis: American Indian Potter 31 Box 14: Book: Lucy Lewis: American Indian Potter 31 Box 15: Book: The Living Tradition of Maria Martinez 32 Box 16: Book: Maria Martinez: Five Generations of Potters 33 Box 17: Book: Shoji Hamada: A Potter’s Way and Work 34 Box 18: Book: Shoji -

Summer 2017 Edition

ATADA NEWSSummer 2017 / Vol. 27-2 Honoring The Artistic Legacy Of Indigenous People Mark A. Johnson Tribal Art Traditional Art from Tribal Asia and the Western Pacific Islands Female Ancestral Figure Flores Island, Indonesia 19th Century Height 18” (45.7cm) www.tribalartmagazine.com 578 Washington Bl. #555 Tribal Art magazine is a quarterly publication dedicated exclusively to the arts and culture of Marina del Rey, CA 90292 the traditional peoples of Africa, Oceania, Asia and the Americas. [email protected] - Tel. : +32 (0) 67 877 277 [email protected] markajohnson.com 2 Summer 2017 In The News... Save The Date Summer 2017 | Vol 27-2 Honoring The Artistic Legacy Of Indigenous People August 12, 2017 Board of Directors: Letter from the President / Editor’s Desk 6 President John Molloy Vice President Kim Martindale In Memoriam 8 Executive Director David Ezziddine Roger Fry Remembered Education Comm Chair Barry Walsh ATADA Foundation Update Treasurer Steve Begner 10 At Large Mark Blackburn Annual ATADA 2017 Brea Foley Portrait Competition Paul Elmore Elizabeth Evans 13 Calendar of Events August in Santa Fe & Beyond / Trade Show Preview Peter Carl Patrick Mestdagh Member Meeting 24 On Trend Mark Johnson A review of Recent Tribal Art Auctions by Mark Blackburn Editors Paul Elmore Elizabeth Evans Saturday, August 12, 2017 • 6:30 pm - 7:30 pm The Leekya Family: Master Carvers of Zuni 30 Design + Production + David Ezziddine Pueblo Advertising Inquiries [email protected] Musuem of International Folk Art A review of the Albuquerque Museum retrospective by Robert Bauver 706 Camino Lejo, on Museum Hill Santa Fe, New Mexico 87505 ATADA Legal Committee Report Policy Statement: 36 ATADA was established in 1988 to represent STOP II / 2017 Symposium Report professional dealers of antique tribal art, to set ethical and professional standards for the Reception and Curated Tours 50 Legal Briefs trade, and to provide education of the public Notes on Current Events in the valuable role of tribal art in the wealth to follow the meeting from of human experience. -

Women's Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award

C13831W1_C13831W1 1/31/13 12:31 PM Page 1 WOMEN’S CAUCUS FOR ART Honor Awards For Lifetime Achievement In The Visual Arts Tina Dunkley Artis Lane Susana Torruella Leval Joan Semmel C13831W1_C13831W1 1/31/13 12:31 PM Page 2 C13831W1_C13831W1 1/31/13 12:31 PM Page 3 Thursday, February 14th New York, NY Introduction Priscilla H. Otani WCA National Board President, 2012–14 Presentation of Lifetime Achievement Awards Tina Dunkley Essay by Jerry Cullum. Presentation by Brenda Thompson. Artis Lane Essay and Presentation by Jarvis DuBois. Susana Torruella Leval Essay by Anne Swartz. Presentation by Susan Del Valle. Joan Semmel Essay by Gail Levin. Presentation by Joan Marter. Presentation of President’s Art & Activism Award Leanne Stella Presentation by Priscilla H. Otani. C13831W1_C13831W1 1/31/13 12:31 PM Page 4 LTA Awards—Foreword and Acknowledgments In 2013, we celebrate the achievements of four highly at El Museo del Barrio and soon to be director of the Sugar creative individuals: Tina Dunkley, director of the Clark Hill Children’s Museum of Art & Storytelling in Harlem, will Atlanta University Art Galleries; sculptor Artis Lane; introduce Leval at the ceremony. Jerry Cullum, freelance Susana T. Leval, Director Emerita of El Museo del Barrio; curator and critic, who for many years served in various and painter Joan Semmel. Each woman has made a unique editorial positions at Art Papers, has written an engaging contribution to the arts in America. Through sustained and essay about Dunkley’s work, and Brenda Thompson, insightful curatorial practice, two of this year’s honorees collector of African American art of the diaspora, will have brought national attention to the significant present her at the awards ceremony. -

Newsletter Fall 2014 Cake Saw, Cut, Engraved and Stamped Silver; 27.6 X 4.1 X 0.2 Cm (10 7/8 X 1 5/8 X 1/16 In.)

newsletter fall 2014 Volume 22, Number 2 Decorative Arts Society DAS Newsletter Volume 22 Editor Gerald W.R. Ward Number 2 Senior Consulting Curator & Fall 2014 Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator of American Decorative Arts and The DAS Sculpture Emeritus The DAS Newsletter is a publication Museum of Fine Arts, Boston of the Decorative Arts Society, Inc. The Boston, MA purpose of the DAS Newsletter is to serve as The Decorative Arts Society, Inc., is a a forum for communication about research, exhibitions, publications, conferences and Coordinator founded in 1990 for the encouragement other activities pertinent to the serious Ruth E. Thaler-Carter ofnot-for-profit interest in, theNew appreciation York corporation of, and the study of international and American deco- Freelance Writer/Editor exchange of information about the rative arts. Listings are selected from press Rochester, NY decorative arts. To pursue its purposes, releases and notices posted or received the Society sponsors meetings, programs, from institutions, and from notices submit- Advisory Board seminars, tours and a newsletter on the ted by individuals. We reserve the right Michael Conforti decorative arts. Its supporters include to reject material and to edit material for Director museum curators, academics, collectors length or clarity. Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute and dealers. We do not cover commercial galleries. Williamstown, MA The DAS Newsletter welcomes submis- Officers sions, preferably in digital format, by e-mail Wendy Kaplan President in Plain Text or as Word attachments, or Department Head and Curator, David L. Barquist on a CD and accompanied by a paper copy. Decorative Arts and Design H. -

W Omen'scaucusforart 2010Honoraw Ards

Tritobia Hayes Benjamin Mary Jane Jacob Senga Nengudi Joyce J. Scott Spiderwoman Theater HONOR AWARDS FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT IN THE VISUAL ARTS WOMEN’S CAUCUS FOR ART 2010 HONOR AWARDS 2010 Honor Awards Saturday, February th Chicago Cultural Center Introduction Marilyn J. Hayes WCA National Board President, 2008–10 Presentation of Lifetime Achievement Awardees Tritobia Hayes Benjamin Essay and Presentation by Lisa Farrington Mary Jane Jacob Essay by Michael Brenson. Presentation by Jacquelynn Baas Senga Nengudi Essay by Lowery Stokes Sims. Presentation by Maren Hassinger Joyce J. Scott Essay by Leslie King-Hammond. Presentation by Sonya Clark Spiderwoman =eater (Lisa Mayo, Gloria Miguel, Muriel Miguel) Essay by Tonya Gonnella Frichner. Presentation by Murielle Borst President’s Awards Juana Guzman Karen Reimer Presentation by Marilyn J. Hayes Foreword and Acknowledgements This year’s ceremony gives the Women’s Caucus for Art College of Art, has given a profound recounting of the opportunity to appreciate and recognize the Joyce J. Scott’s use of the bead as the individual unit by accomplishments of women who have achieved which the artist has created a seemingly infinite lexicon impressive standing in the fields of the visual arts. We of visual forms. Sonya Clark, artist and Chair of the honor four individuals and one theater collective of Craft/Material Studies Department at Virginia three women with the Lifetime Achievement Award. Commonwealth University, will present Joyce with the They are Tritobia Hayes Benjamin, Mary Jane Jacob, award. Senga Nengudi, Joyce J. Scott, and Spiderwoman Theater (Lisa Mayo, Gloria Miguel, and Muriel Miguel). Attorney Tonya Gonnella Frichner, who serves as the We honor these seven women because they have North American Representative of the United Nations embraced with vigor and strength passionate Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, has detailed positions, dedicating themselves each to forging new the accomplishments of the three women of directions in their respective areas. -

Modern Native American Art Los Angeles I September 16, 2019

Traditional/Individual: Modern American Art Native Traditional/Individual: I Los Angeles September 16, 2019 25630 Traditional/Individual: Modern Native American Art Los Angeles I September 16, 2019 Traditional/Individual: Modern Native American Art Los Angeles | September 16, 2019 at 11am BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES REGISTRATION 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard +1 323 850 7500 Ingmars Lindbergs, Director IMPORTANT NOTICE Los Angeles, CA 90046 +1 323 850 6090 (fax) [email protected] Please note that all customers, bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (415) 503 3393 irrespective of any previous activity with Bonhams, are required to PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit Kim Jarand, Specialist complete the Bidder Registration Friday September 13, www.bonhams.com/25630 [email protected] Form in advance of the sale. The 12pm to 5pm +1 (323) 436 5430 form can be found at the back Saturday September 14, Please note that telephone bids of every catalogue and on our 12pm to 5pm must be submitted no later than ILLUSTRATIONS website at www.bonhams.com Sunday September 15, 4pm on the day prior to the Front cover: Lot 4 and should be returned by email or 12pm to 5pm auction. New bidders must also Back cover: Lot 18 post to the specialist department Monday September 16, provide proof of identity and Session page: Lot 48 or to the bids department at 9am to 11am address when submitting bids. [email protected] Please contact client services with any bidding inquiries. To bid live online and / or leave internet bids please go to SALE NUMBER: 25630 LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS www.bonhams.com/auctions/25630 Lots 1 - 78 AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE and click on the Register to bid link Please email: at the top left of the page. -

The Morgan Collection of Southwest Pottery Website Research and Photography

THE MORGAN COLLECTION OF SOUTHWEST POTTERY WEBSITE RESEARCH AND PHOTOGRAPHY A PROJECT By Julie Ann Schrader B.A. Wichita State University, Wichita, Kansas 2002 Submitted to the Department of Anthropology and the Faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Spring 2005 Wichita State University Wichita, Kansas Master of Arts Degree Project We hereby concur that Julie A. Schrader on 4/22/05 has offered a presentation as a requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology. This Master of Arts degree project is titled, The Morgan Collection of Southwest Pottery Website: Research and Photography. Change of grade forms for previously assigned incompletes will be submitted. The results are circled below: Examining Committee Member’s Signatures Pass-Fail 1. Chair David T. Hughes, Ph.D. Pass-Fail 2. Member Peer H. Moore-Jansen, Ph.D. Pass-Fail 3. Member Jay Price, Ph.D. Pass-Fail 4. Member Dorothy Billings, Ph.D. Pass-Fail 3. Member Jerry Martin, M.A. Graduate coordinator will sign and forward to the Graduate School on receiving the bindery receipt. Graduate Coordinator_______________________________________ Clayton Robarchek TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION………………………………………………………………………………………. VI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………………….. VII TABLE OF FIGURES…………………………………………………………………………………… V CHAPTER I: THE MORGAN COLLECTION WEBSITE PROJECT………………… 1 CHAPTER II: PHOTOGRAPHY AND RESEARCH METHODS……………………. 5 PHOTOGRAPHING THE POTS……………………………………………………………………