The Great White Awakening to Black Humanity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Talking Book Topics September-October 2019

Talking Book Topics September–October 2019 Volume 85, Number 5 Need help? Your local cooperating library is always the place to start. For general information and to order books, call 1-888-NLS-READ (1-888-657-7323) to be connected to your local cooperating library. To find your library, visit www.loc.gov/nls and select “Find Your Library.” To change your Talking Book Topics subscription, contact your local cooperating library. Get books fast from BARD Most books and magazines listed in Talking Book Topics are available to eligible readers for download on the NLS Braille and Audio Reading Download (BARD) site. To use BARD, contact your local cooperating library or visit nlsbard.loc.gov for more information. The free BARD Mobile app is available from the App Store, Google Play, and Amazon’s Appstore. About Talking Book Topics Talking Book Topics, published in audio, large print, and online, is distributed free to people unable to read regular print and is available in an abridged form in braille. Talking Book Topics lists titles recently added to the NLS collection. The entire collection, with hundreds of thousands of titles, is available at www.loc.gov/nls. Select “Catalog Search” to view the collection. Talking Book Topics is also online at www.loc.gov/nls/tbt and in downloadable audio files from BARD. Overseas Service American citizens living abroad may enroll and request delivery to foreign addresses by contacting the NLS Overseas Librarian by phone at (202) 707-9261 or by email at [email protected]. Page 1 of 84 Music scores and instructional materials NLS music patrons can receive braille and large-print music scores and instructional recordings through the NLS Music Section. -

House Committee on Judiciary & Civil Jurisprudence Hb 19

PUBLIC COMMENTS HB 19 HOUSE COMMITTEE ON JUDICIARY & CIVIL JURISPRUDENCE Hearing Date: March 9, 2021 10:00 AM Michael Gerke SELF Missouri City, TX This bill rewards bad actors. That is, companies who fail to train and properly hire drivers get to be dismissed from a case against them. This is a disincentive to do things the right way. And those companies who do hiring, training and safety the proper way, are placed at an economic disadvantage to those who do not. Bad bill. Texans lose on this one. Jason Boorstein Self Dallas, TX I became very concerned after reading the text of this bill. The bill aims to hurt individuals driving on our roads. I am concerned about commercial vehicles from Texas, other States and Countries getting a pass in Texas if they hurt or kill someone. I am concerned that if this bill passes, companies have less incentive to investigate bad drivers, self police their company, train and discipline. Please consider tabling this bill so that we can investigate the real ramification to Texans. Thank you. Guy Choate Webb, Stokes & Sparks, LLP San Angelo, TX I speak in opposition to this Bill. Texas highways would be made less safe by protecting the companies that put profits over safety as they put unsafe trucks and drivers on the road. Large trucks are disproportionately responsible for carnage on Texas highways. Trucking companies need more scrutiny, not less. Trucks do not have to be dangerous and truck drivers do not have to cause crashes. Good companies do not have the type of crashes that routinely plague Texas highways. -

June 18 – 24, 2020

HAPPY FATHER’S DAY! 2726 S. Beckley Ave • Dallas, Texas 75224 ISSN # 0746-7303 P.O. Box 570769 Dallas, Texas 75357 - 0769 50¢ Serving Dallas More Than 70 Years — Tel. 214 946-7678 - Fax 214 946-7636 — Web Site: www.dallasposttrib.com — E-mail: [email protected] SERVING THE BLACK COMMUNITY WITHOUT FEAR OR FAVOR SINCE 1947 VOLUME 72 NUMBER 40 June 18 - 24, 2020 Juneteenth/Freedom Day, End of Slavery in Texas - Year 1865 A 1908 photograph of two women in Texas sitting in a buggy decorated with flowers for the annual Juneteenth Celebration parked in front of Antioch Baptist Church located in Houston’s Fourth Ward. (Photo Credit - Houston Public Library, African American Library at the Gregory School). A shot from the Juneteenth celebration in 1900 at Eastwoods Park. GRACE MURRAY STEPHENSON, AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER, PICA 05476 American and Juneteenth flags AMERICAN FLAGS OF FREEDOM The Juneteenth Flag is a symbol that gives all Americans the opportunity to recognize American freedom & African American History. The Juneteenth Flag represents a star of Texas bursting with new freedom throughout the land, over a new horizon. The Juneteenth Flag represents a new freedom, a new people, and a new star. The Juneteenth Flag is created with American red, white, and blue colors. The Juneteenth Flag & American Flag Sets & Other items A photo of a band at the 1900 Juneteenth celebration at Eastwoods Park are available for all Americans who cherish and stand for GRACE MURRAY STEPHENSON, AUSTIN HISTORY CENTER, PICA 05481 freedom. The Story U.S.C.T. -

Black Lives Matter: on Racism and Political Correctness

Essays | 26 June 2020 Black lives Matter: On Racism and Political Correctness Azmi Bishara Black lives Matter: On Racism and Political Correctness Series: Essays 26 June 2020 Azmi Bishara General Director and Member of the Board of Directors of the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. Dr Bishara is a researcher and writer with numerous books and publications on political thought, social theory and philosophy, as well as some literary works. He taught philosophy and cultural studies at Birzeit University from 1986 to 1996, and was involved in the establishment of research centers in Palestine including the Palestinian Institute for the Study of Democracy (Muwatin) and the Mada al-Carmel Center for Applied Social Research. Copyright © 2020 Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies. All Rights Reserved. The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies is an independent research institute and think tank for the study of history and social sciences, with particular emphasis on the applied social sciences. The Center’s paramount concern is the advancement of Arab societies and states, their cooperation with one another and issues concerning the Arab nation in general. To that end, it seeks to examine and diagnose the situation in the Arab world - states and communities- to analyze social, economic and cultural policies and to provide political analysis, from an Arab perspective. The Center publishes in both Arabic and English in order to make its work accessible to both Arab and non- Arab researchers. The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies Al-Tarfa Street, Wadi Al Banat Al-Dayaen, Qatar PO Box 10277, Doha +974 4035 4111 www.dohainstitute.org Black lives Matter: On Racism and Political Correctness Series: Essays Table of Contents 26 June 2020 I. -

White Backlash in a Brown Country

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 50 Number 1 Fall 2015 pp.89-132 Fall 2015 White Backlash in a Brown Country Terry Smith DePaul University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Terry Smith, White Backlash in a Brown Country, 50 Val. U. L. Rev. 89 (2015). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol50/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Smith: White Backlash in a Brown Country Lecture WHITE BACKLASH IN A BROWN COUNTRY Terry Smith I would like to honestly say to you that the white backlash is merely a new name for an old phenomenon . It may well be that shouts of Black Power and riots in Watts and the Harlems and the other areas, are the consequences of the white backlash rather than the cause of them.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 90 II. PRIVILEGE AS ADDICTION, DEMOGRAPHY AS THREAT: EXPLAINING THE ETIOLOGY OF BACKLASH ........................................................................... 94 III. BACKLASH AND THE REVIVIFICATION OF CLASSICAL RACISM ............... 105 A. A Creeping “New White Nationalism?” .................................................. 106 B. The Othering of a President ...................................................................... 113 IV. WHITE BACKLASH AT THE BALLOT BOX: THE FIRE NEXT TIME ............ 117 A. From Inevitability to Backlash: Fallacies, Fears, and Suppression .......... 118 1. (Mis)Counting on Latinos .................................................................... -

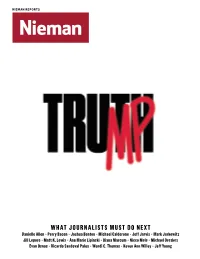

WHAT JOURNALISTS MUST DO NEXT Danielle Allen • Perry Bacon • Joshua Benton • Michael Calderone • Jeff Jarvis • Mark Jurkowitz Jill Lepore • Matt K

NIEMAN REPORTS WHAT JOURNALISTS MUST DO NEXT Danielle Allen • Perry Bacon • Joshua Benton • Michael Calderone • Jeff Jarvis • Mark Jurkowitz Jill Lepore • Matt K. Lewis • Ann Marie Lipinski • Diana Marcum • Nicco Mele • Michael Oreskes Evan Osnos • Ricardo Sandoval Palos • Wendi C. Thomas • Keven Ann Willey • Jeff Young Contributors The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University www.niemanreports.org Keith O’Brien (page 6) is a former reporter for The Boston Globe, a correspondent for National Public Radio, and author. He has written for The New York Times Magazine, Politico, and Slate, among other publications. Gabe Bullard (page 12) is the senior publisher producer, digital and strategy, for 1A, a new Ann Marie Lipinski public radio show launching in 2017 on editor stations across the country. A 2015 Nieman James Geary Fellow, he is the former deputy director of senior editor digital news at National Geographic. Jan Gardner editorial assistant Carla Power (page 20) is the author of the Eryn M. Carlson 2016 Pulitzer finalist “If the Oceans Were design Ink: An Unlikely Friendship and a Journey to Pentagram the Heart of the Quran,” about her studies Donald Trump’s rise to the presidency is being viewed by journalists and historians as an important time to reflect on the best way to move forward editorial offices with a traditional Islamic scholar. She is a One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, former correspondent for Newsweek. MA 02138-2098, 617-496-6308, Contents Fall 2016 / Vol. 70 / No. 4 [email protected] Naomi Darom (page 26), a 2016 Nieman Copyright 2016 by the President and Features Departments Fellows of Harvard College. -

Assessing the Validity of an Election's Result

FOLEY-LIVE(DO NOT DELETE) 9/24/2020 6:21 PM ASSESSING THE VALIDITY OF AN ELECTION’S RESULT: HISTORY, THEORY, AND PRESENT THREATS EDWARD B. FOLEY* In the wake of President Trump’s acquittal in the Senate impeachment trial, and even more so because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States will need to hold a presidential election in unprecedented circumstances. Never before has an incumbent president run for reelection after the opposing party in Congress has declared that the fairness of the election cannot be “assured” as long as the incumbent is permitted on the ballot. Nor have states been required to plan for a November presidential election not knowing, because of pandemic-related uncertainties, the extent to which voters will be able to go to the polls to cast ballots in person rather than needing to do so by mail. These uniquely acute challenges to holding an election that the public will accept as valid follow other stresses to electoral legitimacy unseen before 2016. The Russian attack on the 2016 election caused Americans to question, in an unprecedented way, the nation’s capacity to hold free and fair elections. Given these challenges, this essay tackles the basic concept of what it means for the outcome of an election to be valid. Although this concept had been considered settled before 2016, developments since then have caused it to become contested. Current circumstances require renewing a shared conception of electoral validity. Otherwise, participants in electoral competition—winners and losers alike—cannot know whether or not the result qualifies as authentically democratic. -

You Shook Me All Campaign Long

You Shook Me All Campaign Long You Shook Me All Campaign Long Music in the 2016 Presidential Election and Beyond EDITED BY Eric T. Kasper and Benjamin S. Schoening ©2018 University of North Texas Press All rights reserved. Printed in Canada 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Permissions: University of North Texas Press 1155 Union Circle #311336 Denton, TX 76203-5017 The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, z39.48.1984. Binding materials have been chosen for durability. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kasper, Eric T., author, editor, writer of introduction. | Schoening, Benjamin S., 1978- editor, writer of introduction. Title: You shook me all campaign long : music in the 2016 presidential election and beyond / edited by Eric T. Kasper and Benjamin S. Schoening. Description: Denton, Texas : University of North Texas Press, [2018] | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018030231| ISBN 9781574417340 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781574417456 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Music--Political aspects--United States--History--21st century. | Presidents--United States--Election--2016. | Campaign songs--United States--21st century--History and criticism. Classification: LCC ML3917.U6 Y68 2018 | DDC 781.5/990973090512--dc23 LC record available at https://na01.safelinks.protection.outlook.com/?url=https%3A %2F%2Flccn.loc.gov%2F2018030231&data=01%7C01%7Ckaren.devinney %40unt.edu%7Cbc7ee94d4ce24da8c61108d5fd2b629f %7C70de199207c6480fa318a1afcba03983%7C0&sdata=RCKaP2yvdh4Uwe1bo7RKlObBDeb %2FvX3n35WV8ddVCfo%3D&reserved=0 The electronic edition of this book was made possible by the support of the Vick Family Foundation. Table of Contents Introduction: Tippecanoe and Trump Too Eric T. -

The Nation July 13/20, 2020 Issue

DE BLASIO: AN UNENDORSEMENT TRUMP’S UNDERTAKER THE EDITORS PATRICIA J. WILLIAMS JULY 13/20, 2020 Defund Just the Invest Police This is only the How to make beginning it a reality DESTIN JENKINS BRYCE COVERT We must avoid exchanging the violence of the police for the violence of finance capitalism THENATION.COM Version 01-08-2020 ON TARA READE’S ALLEGATIONS KATHA POLLITT ALABAMA COMMUNISTS 2 The Nation. ROBERT GREENE II JUNE 15/22, 2020 Join the conversation, SPECIAL ISSUE In times every Thursday, of crisis, ideas that were once considered radical can enter the on the Start Making Letters mainstream. @thenation.com MIKE Sense podcast. DAVIS ZOË CARPENTER JANE MCALEVEYB ELIE MYSTAL IG BRYCE COVERT BILL FLETCHER JR. JOHN NICHOLS JULIAN BRAVE NOISECAT Time to THENATION.COM Think A Gamble Worth Taking to continue to obstruct the revolution that single-payer would mean for all Bill Fletcher Jr.’s wish list for the working people. Brent Kramer reinvention of organized labor brooklyn [“Labor: More Perfect Unions,” June 15/22] is, as usual with him, Protect Old Joe? insightful and incisive. Re “On Tara Reade’s Allegations” Subscribe wherever you But his prescription for the crisis [Katha Pollitt, June 15/22]: I am get your podcasts or go to in health care costs is just plain wrong. very disappointed by what seems to TheNation.com/ To say that “unions should, of course, be an all-out effort in The Nation to StartMakingSense defend the health plans that they dis credit and humiliate Tara Reade to listen today. have” is saying that union leadership and bolster Joe Biden’s reputation. -

Congressional Record—House H1039

March 3, 2021 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H1039 Zimbabwe and to maintain in force the in the Federal Register and transmits to Mr. RODNEY DAVIS of Illinois. Mr. sanctions to respond to this threat. the Congress a notice stating that the Speaker, on that I demand the yeas JOSEPH R. BIDEN, Jr. emergency is to continue in effect be- and nays. THE WHITE HOUSE, March 2, 2021. yond the anniversary date. In accord- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Pursu- f ance with this provision, I have sent to ant to section 3(s) of House Resolution the Federal Register for publication the 8, the yeas and nays are ordered. CONTINUATION OF THE NATIONAL enclosed notice stating that the na- Pursuant to clause 8 of rule XX, fur- EMERGENCY WITH RESPECT TO tional emergency declared in Executive ther proceedings on this question are UKRAINE—MESSAGE FROM THE Order 13692 of March 8, 2015, with re- postponed. PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED spect to the situation in Venezuela is Pursuant to clause 1(c) of rule XIX, STATES (H. DOC. NO. 117–21) to continue in effect beyond March 8, further consideration of H.R. 1 is post- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- 2021. poned. fore the House the following message The situation in Venezuela continues f from the President of the United to pose an unusual and extraordinary States; which was read and, together threat to the national security and for- GEORGE FLOYD JUSTICE IN with the accompanying papers, referred eign policy of the United States. There- POLICING ACT OF 2021 to the Committee on Foreign Affairs fore, I have determined that it is nec- Mr. -

Foreword: the Degradation of American Democracy—And the Court

VOLUME 134 NOVEMBER 2020 NUMBER 1 © 2020 by The Harvard Law Review Association THE SUPREME COURT 2019 TERM FOREWORD: THE DEGRADATION OF AMERICAN DEMOCRACY — AND THE COURT† Michael J. Klarman CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 4 I. THE DEGRADATION OF AMERICAN DEMOCRACY ............................................................ 11 A. The Authoritarian Playbook ............................................................................................. 11 B. President Trump’s Authoritarian Bent ............................................................................ 19 1. Attacks on Freedom of the Press and Freedom of Speech .......................................... 20 2. Attacks on an Independent Judiciary .......................................................................... 22 3. Politicizing Law Enforcement ...................................................................................... 23 4. Politicizing the Rest of the Government ...................................................................... 25 5. Using Government Office for Private Gain .................................................................. 28 6. Encouraging Violence .................................................................................................... 32 7. Racism ............................................................................................................................. 33 8. Lies .................................................................................................................................. -

Indem Tour ‘Knocks the Rust Off’ Schmuhl Finds Statewide Tour Energizes Base, Brings Earned Media, Helps Recruitment by BRIAN A

V26, N40 Thursday, July 1, 2021 INDem tour ‘knocks the rust off’ Schmuhl finds statewide tour energizes base, brings earned media, helps recruitment By BRIAN A. HOWEY INDIANAPOLIS – While the crowds were somewhat modest coming in the summer of the quadrennial non- election year, the Indiana Democrats’ American Rescue Plan tour aimed at all 92 counties created news coverage deep in the heart of Hoosier Trump country that was notable, if not signifi- Indiana Democratic “State Democrats tout Chairman Mike cant. local successes of ARP.” Schmuhl talks in Ripley In the article by Indiana Democratic Chairman County. Mike Schmuhl knew he had to begin his the Tribune’s Jared party rebuild by showing up in some of the most Republi- Keever, the lead was: can counties in the state. In Miami County, where Donald “Indiana Democrats are Trump bludgeoned Joe Biden 75-22% last November, State finishing a five-week tour of the state touting successes of Sen. J.D. Ford and State Rep. Earl Harris Jr., showed up to federal legislation that has pumped millions of dollars into make the pitch. They did so in the tiny town of Denver. It resulted in the Peru Tribune banner headline, Continued on page 3 Our inflation problem By LARRY DeBOER WEST LAFAYETTE – We’ve got an inflation prob- lem. What should we do about it? That depends on what kind of inflation problem we’ve got. In May the consumer price index was 4.9% higher “I am most grateful for the way than it was 12 months before. The last time we saw an inflation the Holcomb administration has rate that high was July 2008.