The Multi-Layered Transnationalism of Fran Palermo Ewa Mazierska And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

the First Hungarian Beat Movie (1967) Ádám Ignácz (Budapest)

EZEK A FIATALOK. The First Hungarian Beat Movie (1967) Ádám Ignácz (Budapest) On a summer afternoon in 1967, Balatonlelle was preparing for an unusual event. Contrary to the common practice of selecting a well-known cinema of Budapest, the premiere of the new Hungarian music film, EZEK A FIATALOK [THESE YOUNGSTERS] was scheduled in the unknown open-air film theatre of this small village resort by Lake Balaton, some 140 kilometres away from the capital city. But in contradiction to the expectations, thousands of people, mostly youngsters, watched the film there during a very short period of time, and later on its popularity expanded further significantly. When the film was screened in film theatres and cultural-educational centres around the country during the following months, the estimated number of viewers hit almost a million. Even though the better part of the early articles and reviews highlighted its weak points, the sheer number of them indicated that the director Tamás Banovich (1925–2015) had found a subject of utmost interest to the entirety of Hungarian society. The extraordinary success and popularity can be explained by the mere fact that within the framework of a simple plot, EZEK A FIATALOK provided a platform for the most prominent contemporary Hungarian beat bands to present their works. In 1967, more than ten years after the first Elvis films had combined the features of popular music and motion picture, The Beatles already stopped giving concerts, and in the West people were talking about the end of the first phase of traditional beat music and were celebrating the birth of new KIELER BEITRÄGE ZUR FILMMUSIKFORSCHUNG, 12, 2016 // 219 genres in pop and rock music. -

Named Entity Recognition for Search Queries in the Music Domain

DEGREE PROJECT IN COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING, SECOND CYCLE, 30 CREDITS STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2016 Named Entity Recognition for Search Queries in the Music Domain SANDRA LILJEQVIST KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF COMPUTER SCIENCE AND COMMUNICATION Named Entity Recognition for Search Queries in the Music Domain SANDRA LILJEQVIST [email protected] Master’s Thesis in Computer Science School of Computer Science and Communication KTH Royal Institute of Technology Supervisor: Olov Engwall Examiner: Viggo Kann Principal: Spotify AB Stockholm - June 2016 Abstract This thesis addresses the problem of named entity recogni- tion (NER) in music-related search queries. NER is the task of identifying keywords in text and classifying them into predefined categories. Previous work in the field has mainly focused on longer documents of editorial texts. However, in recent years, the application of NER for queries has attracted increased attention. This task is, however, ac- knowledged to be challenging due to queries being short, ungrammatical and containing minimal linguistic context. The usage of NER for queries is especially useful for the implementation of natural language queries in domain- specific search applications. These applications are often backed by a database, where the query format otherwise is restricted to keyword search or the usage of a formal query language. In this thesis, two techniques for NER for music-related queries are evaluated; a conditional random field based so- lution and a probabilistic solution based on context words. As a baseline, the most elementary implementation of NER, commonly applied on editorial text, is used. Both of the evaluated approaches outperform the baseline and demon- strate an overall F1 score of 79.2% and 63.4% respectively. -

José/Before JOHN5

23 Season 2012-2013 Sunday, April 14, at 3:00 28th Season of Chamber The Philadelphia Orchestra Music Concerts—Perelman Theater Holló José/beFORe John5, for percussion quartet Christopher Deviney Percussion Víctor Pablo García-Gaetán Percussion (Guest) Bradley Loudis Percussion (Guest) Phillip O’Banion Percussion (Guest) Reich from Drumming: Part I Part II Christopher Deviney Percussion Víctor Pablo García-Gaetán Percussion (Guest) Bradley Loudis Percussion (Guest) Phillip O’Banion Percussion (Guest) Temple University Percussion Ensemble (Guests) Spivack Scherzo for Percussion Septet and Forty Instruments Christopher Deviney Percussion Víctor Pablo García-Gaetán Percussion (Guest) Bradley Loudis Percussion (Guest) Phillip O’Banion Percussion (Guest) Temple University Percussion Ensemble (Guests) Intermission Bartók String Quartet No. 3 (In one movement) Marc Rovetti Violin William Polk Violin Kerri Ryan Viola Yumi Kendall Cello Beethoven String Quartet No. 2 in G major, Op. 18, No. 2 I. Allegro II. Adagio cantabile III. Scherzo: Allegro IV. Allegro molto quasi presto Marc Rovetti Violin William Polk Violin Kerri Ryan Viola Yumi Kendall Cello This program runs approximately 1 hour, 55 minutes. 224 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin Renowned for its distinctive vivid world of opera and Orchestra boasts a new sound, beloved for its choral music. partnership with the keen ability to capture the National Centre for the Philadelphia is home and hearts and imaginations Performing Arts in Beijing. the Orchestra nurtures of audiences, and admired The Orchestra annually an important relationship for an unrivaled legacy of performs at Carnegie Hall not only with patrons who “firsts” in music-making, and the Kennedy Center support the main season The Philadelphia Orchestra while also enjoying a at the Kimmel Center for is one of the preeminent three-week residency in the Performing Arts but orchestras in the world. -

Emília Barna and Tamás Tófalvy (2017). Made in Hungary: Studies in Popular Music, 1St Ed

HStud 31(2017)2 285–294 DOI: 10.1556/044.2017.32.1.12 EMÍLIA BARNA AND TAMÁS TÓFALVY (2017). MADE IN HUNGARY: STUDIES IN POPULAR MUSIC, 1ST ED. NEW YORK: ROUTLEDGE, 192. Reviewed by Adam Havas Now that the Hungarian volume of the Routledge Global Popular Music Series, Made in Hungary: Studies in Popular Music (Barna and Tófalvy, 2017) has come out, popular music scholarship has clearly arrived at a new stage in Hungary. The collection of fourteen studies on the historical development, sociological approaches and musicology of Hungarian popular music embraces half a century, from postwar state socialism to contemporary issues associated with a wide range of topics. The contributors, affi liated with universities of the most important intel- lectual centers in the country, such as Budapest, Debrecen, and Pécs, are trained in various disciplines from sociology to musicology, history, communication and philosophy, thus the reader encounters not only an array of issues discussed in the chapters, but diff erent angles of investigation depending on the above listed disciplinary practices. The creation of the colorful panorama off ered by the chapters was guided by the editorial principle of making clear the context for international audiences pre- sumably unfamiliar with the country-specifi c social and cultural factors shaping the scholarly discourse within this fi eld. For that reason, the historical narrative of popular music research also plays an important role in the book, which aims to cover the major fi gures, issues and contexts of its subject matter. From an insider perspective, as the author of the current review is a member of the Hungarian IASPM community, it is remarkable that the volume also strength- ens the identity of this relatively small and fragmented research community of Hungarian scholars who dedicate themselves to this often neglected, quasi-legit- imate research area, shadowed by “grand themes” such as social stratifi cation, poverty or even classical music research. -

Social Networks in Movement

Contacts. Social Dynamics in the Czech State-Socialist Art World Svasek, M. (2002). Contacts. Social Dynamics in the Czech State-Socialist Art World. Contemporary European History, 8. Published in: Contemporary European History Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:27. Sep. 2021 Social Networks in Movement. Time, interaction and interethnic spaces in Central Eastern Europe Edited by Davide Torsello and Melinda Pappová NOSTRA TEMPORA, 8. General Editor: Károly Tóth Forum Minority Research Institute Šamorín, Slovakia Social Networks in Movement. Time, interaction and interethnic spaces in Central Eastern Europe Edited by Davide TORSELLO and Melinda PAPPOVÁ Forum Minority Research Institute Lilium Aurum Šamorín - Dunajská Streda 2003 © Forum Minority Research Institute, 2003 © Davide Torsello, Melinda Pappová, 2003 ISBN 80-8062-179-9 Contents 5 Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .....................................................................7 Studying networks nowadays. On the utility of a notion (C. -

Old and New Islam in Greece Studies in International Minority and Group Rights

Old and New Islam in Greece Studies in International Minority and Group Rights Series Editors Gudmundur Alfredsson Kristin Henrard Advisory Board Han Entzinger, Professor of Migration and Integration Studies (Sociology), Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Baladas Ghoshal, Jawaharlal Nehru University (Peace and Confl ict Studies, South and Southeast Asian Studies), New Delhi, India; Michelo Hansungule, Professor of Human Rights Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa; Baogang He, Professor in International Studies (Politics and International Studies), Deakin University, Australia; Joost Herman, Director Network on Humani tarian Assistance the Netherlands, the Netherlands; Will Kymlicka, Professor of Political Philosophy, Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada; Ranabir Samaddar, Director, Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group Kolkata, India; Prakash Shah, Senior Lecturer in Law (Legal Pluralism), Queen Mary, University of London, the United Kingdom; Tove Skutnabb-Kangas, Guest Researcher at the Department of Languages and Culture, University of Roskilde, Denmark; Siep Stuurman, Professor of History, Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands; Stefan Wolfff, Professor in Security Studies, University of Birmingham, the United Kingdom. VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/imgr Old and New Islam in Greece From Historical Minorities to Immigrant Newcomers By Konstantinos Tsitselikis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tsitselikis, Konstantinos. Old and new Islam in Greece : from historical minorities to immigrant newcomers / by Konstantinos Tsitselikis. p. cm. -- (Studies in international minority and group rights ; v. 5) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-22152-9 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Muslims--Legal status, laws, etc.--Greece. 2. Minorities--Legal status, laws, etc.--Greece. 3. -

The Music of the Roma in Hungary

Data » Music » Countries » The music of the Roma in Hungary http://romani.uni-graz.at/rombase The music of the Roma in Hungary Katalin Kovalcsik Traditionally there are two kinds of music performed by the Roma: one is musical service rendered for non-Romani audiences, the other is music made within the Romani community. The music played for outsiders is labelled "Gypsy music" by Hungarian scientific literature having adopted its colloquial name, and the music they use among themselves is called "folk music". At the same time, the Roma began gradually to develop an ethnic music culture from the 1970s. The process of creating the institutional conditions for the practising, improvement and presentation of their own culture picked up momentum when after the great political turn they obtained national minority status. In the following, I first give a sketchy summary of the two traditional cultural modes, before listing the main tendencies asserted in today's Romani music life in Hungary. The table below shows the Romani ethnic groups in Hungary and their traditional occupations (after Kemény 1974). The major ethnic groupings of the Roma living in Hungary The name of the First language Proportion according to Traditional occupations grouping (in brackets their first language their own name) within the Romani population, in % Hungarian (romungro) Hungarian ca 71 music making in musician dynasties, metal-working, brick-making, agricultural labour etc. Vlach (vlašiko) Romani- Hungarian ca 21 metal-working, sieve-making, horse-dealing, trading etc. Boyash (băiaş) Romanian- Hungarian ca 8 wood-working (tubs, spoons, other wooden household utensils) Slovak (serviko) Romani- Hungarian No data. -

10,000 Maniacs Beth Orton Cowboy Junkies Dar Williams Indigo Girls

Madness +he (,ecials +he (katalites Desmond Dekker 5B?0 +oots and Bob Marley 2+he Maytals (haggy Inner Circle Jimmy Cli// Beenie Man #eter +osh Bob Marley Die 6antastischen BuBu Banton 8nthony B+he Wailers Clueso #eter 6oA (ean #aul *ier 6ettes Brot Culcha Candela MaA %omeo Jan Delay (eeed Deichkind 'ek181Mouse #atrice Ciggy Marley entleman Ca,leton Barrington !e)y Burning (,ear Dennis Brown Black 5huru regory Isaacs (i""la Dane Cook Damian Marley 4orace 8ndy +he 5,setters Israel *ibration Culture (teel #ulse 8dam (andler !ee =(cratch= #erry +he 83uabats 8ugustus #ablo Monty #ython %ichard Cheese 8l,ha Blondy +rans,lants 4ot Water 0ing +ubby Music Big D and the+he Mighty (outh #ark Mighty Bosstones O,eration I)y %eel Big Mad Caddies 0ids +able6ish (lint Catch .. =Weird Al= mewithout-ou +he *andals %ed (,arowes +he (uicide +he Blood !ess +han Machines Brothers Jake +he Bouncing od Is +he ood -anko)icDescendents (ouls ')ery +ime !i/e #ro,agandhi < and #elican JGdayso/static $ot 5 Isis Comeback 0id Me 6irst and the ood %iddance (il)ersun #icku,s %ancid imme immes Blindside Oceansi"ean Astronaut Meshuggah Con)erge I Die 8 (il)er 6ear Be/ore the March dredg !ow $eurosis +he Bled Mt& Cion 8t the #sa,, o/ 6lames John Barry Between the Buried $O6H $orma Jean +he 4orrors and Me 8nti16lag (trike 8nywhere +he (ea Broadcast ods,eed -ou9 (,arta old/inger +he 6all Mono Black 'm,eror and Cake +unng &&&And -ou Will 0now Us +he Dillinger o/ +roy Bernard 4errmann 'sca,e #lan !agwagon -ou (ay #arty9 We (tereolab Drive-In Bi//y Clyro Jonny reenwood (ay Die9 -

Hungarian Studies 31/2(2017) 0236-6568/$20 © Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest

HStud 31(2017)2 285–294 DOI: 10.1556/044.2017.32.1.12 EMÍLIA BARNA AND TAMÁS TÓFALVY (2017). MADE IN HUNGARY: STUDIES IN POPULAR MUSIC, 1ST ED. NEW YORK: ROUTLEDGE, 192. Reviewed by Adam Havas Now that the Hungarian volume of the Routledge Global Popular Music Series, Made in Hungary: Studies in Popular Music (Barna and Tófalvy, 2017) has come out, popular music scholarship has clearly arrived at a new stage in Hungary. The collection of fourteen studies on the historical development, sociological approaches and musicology of Hungarian popular music embraces half a century, from postwar state socialism to contemporary issues associated with a wide range of topics. The contributors, affi liated with universities of the most important intel- lectual centers in the country, such as Budapest, Debrecen, and Pécs, are trained in various disciplines from sociology to musicology, history, communication and philosophy, thus the reader encounters not only an array of issues discussed in the chapters, but diff erent angles of investigation depending on the above listed disciplinary practices. The creation of the colorful panorama off ered by the chapters was guided by the editorial principle of making clear the context for international audiences pre- sumably unfamiliar with the country-specifi c social and cultural factors shaping the scholarly discourse within this fi eld. For that reason, the historical narrative of popular music research also plays an important role in the book, which aims to cover the major fi gures, issues and contexts of its subject matter. From an insider perspective, as the author of the current review is a member of the Hungarian IASPM community, it is remarkable that the volume also strength- ens the identity of this relatively small and fragmented research community of Hungarian scholars who dedicate themselves to this often neglected, quasi-legit- imate research area, shadowed by “grand themes” such as social stratifi cation, poverty or even classical music research. -

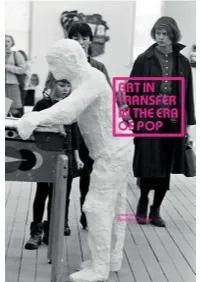

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the -

Hungary and Poland:" Hungary" Stable Partner in Democracy

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 473 223 SO 034 479 AUTHOR Henderson, Steven M. TITLE Hungary and Poland. "Hungary" Stable Partner in Democracy. Building Partnership for Europe: Poland after a Decade System of Transformation. Fulbright-Hayes Summer Seminars Abroad Program, 2002 (Hungary and Poland). SPONS AGENCY Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 88p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Curriculum Development; *Democracy; Economic Factors; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Learning Activities; Political Issues; *Quality of Life; Summer Programs; Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Hungary; *Poland; Social Reality; USSR ABSTRACT This curriculum project provides insight into the transformation processes in which the nations of Hungary and Poland have been participating, from approximately 1979-2002. A major focus of the project is to organize a set of information that teachers and students can analyze and understand the Hungarian and Polish quality of life during the Soviet era and after each nation gained its independence. This curriculum compilation includes four sections:(1) ideas about how educators might use excerpts from the project with students as primary source material;(2) answers to a set of questions asked by the Fulbright seminar participant (the author) about politics, economics, and society in Poland and Hungary;(3) detailed lecture notes from each day of the seminar; -

Alex Ross-Iver Truly Pushes the Boundaries of Experimentalism

Artist - Alex Ross Iver Track title - The Fire Inside ( http://soundcloud.com/alexpopmusic/fire-inside/s-qyrMp ) Written and produced by - Alex Ross Iver and Gisli Kristjansson Label =- Alexpop.com In a world dominated by one dimensional pop music Alex Ross Iver defines everything that a music maverick should epitomize. He is half Georgian and half Russian but none of his family had a musical background in fact both parents had a scientific background an influence which he thinks in part may have led him to appreciate an experimental style relating to all forms of music he created as a youth right up to the present day. Alex has been part of the Moscow club scene for many years, with his Alexpop.com label being marked down as one of the most innovative exponents of avant-garde electro pop outside Europe. He was educated in both Russia and the United States hence giving his music a unique flavor combining experimental pop with an electro edge. His soul mates are the likes of Brian Eno , Phillip Glass , The Knife, Kraftwerk, Yello , through to Yonderboi and La Dusselldorf. In fact pretty much anything that doesn't fit neatly into a packaged music box that makes the listener feel comfortable and at ease. Alex Ross-Iver truly pushes the boundaries of experimentalism. It was this pulsating experimentalism, and thought provokingly complex musical compositions which impressed an equally maverick musician. The Icelandic Gisli Kristjansson , part of the hugely successful Waterfall production team out of Norway and a Number 1 hit maker in his own right who decided to bring in the wonderfully talented Eliza Newman whose band Bellatrix gained huge critical acclaim releasing albums on Bjork's, 'Bad Taste' label , turning her into one of Scandinavia's most talked about and sort after vocalists.