A Statistical Approach to Syllabic Alliteration in the Odyssean Aeneid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intermediate Division Round One

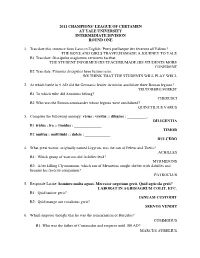

2011 CHAMPIONS’ LEAGUE OF CERTAMEN AT YALE UNIVERSITY INTERMEDIATE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Translate this sentence from Latin to English: Pueri puellaeque iter fecerunt ad Yalium? THE BOYS AND GIRLS TRAVELED/MADE A JOURNEY TO YALE B1 Translate: Discipulus magistrum certiorem facebat. THE STUDENT INFORMED HIS TEACHER/MADE HIS STUDENTS MORE CONFIDENT B2 Translate: Putamus discipulos bene lusuros esse. WE THINK THAT THE STUDENTS WILL PLAY WELL 2. At which battle in 9 AD did the Germanic leader Arminius annihilate three Roman legions? TEUTOBERG FOREST B1 To which tribe did Arminius belong? CHERUSCI B2 Who was the Roman commander whose legions were annihilated? QUINCTILIUS VARUS 3. Complete the following analogy: vrus : vrits :: diligns : __________. DLIGENTIA B1 rtus : ra :: timidus : ______________ TIMOR B2 multus : multitd :: dulcis : _____________ DULCD 4. What great warior, originally named Ligyron, was the son of Peleus and Thetis? ACHILLES B1: Which group of warriors did Achilles lead? MYRMIDONS B2: After killing Clytonomous, which son of Menoetius sought shelter with Achilles and became his favorite companion? PATROCLUS 5. Responde Latine: homines multa agunt. Mercator negotium gerit. Quid agricola gerit? LABORAT IN AGRIS/AGRUM COLIT, ETC. B1: Quid ianitor gerit? IANUAM CUSTODIT B2: Quid mango aut venalicius gerit? SERVOS VENDIT 6. Which emperor thought that he was the reincarnation of Hercules? COMMODUS B1. Who was the father of Commodus and emperor until 180 AD? MARCUS AURELIUS B2. What was the name of Commodus’ mistress, believed to have been a Christian? MARCIA 7. Make the phrase “lx t vrits” accusative plural. LCS T VRITTS B1. Make “lcs t vritts” genitive plural. -

TRADITIONAL POETRY and the ANNALES of QUINTUS ENNIUS John Francis Fisher A

REINVENTING EPIC: TRADITIONAL POETRY AND THE ANNALES OF QUINTUS ENNIUS John Francis Fisher A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY RECOMMENDED FOR ACCEPTANCE BY THE DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS SEPTEMBER 2006 UMI Number: 3223832 UMI Microform 3223832 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 © Copyright by John Francis Fisher, 2006. All rights reserved. ii Reinventing Epic: Traditional Poetry and the Annales of Quintus Ennius John Francis Fisher Abstract The present scholarship views the Annales of Quintus Ennius as a hybrid of the Latin Saturnian and Greek hexameter traditions. This configuration overlooks the influence of a larger and older tradition of Italic verbal art which manifests itself in documents such as the prayers preserved in Cato’s De agricultura in Latin, the Iguvine Tables in Umbrian, and documents in other Italic languages including Oscan and South Picene. These documents are marked by three salient features: alliterative doubling figures, figurae etymologicae, and a pool of traditional phraseology which may be traced back to Proto-Italic, the reconstructed ancestor of the Italic languages. A close examination of the fragments of the Annales reveals that all three of these markers of Italic verbal art are integral parts of the diction the poem. Ennius famously remarked that he possessed three hearts, one Latin, one Greek and one Oscan, which the second century writer Aulus Gellius understands as ability to speak three languages. -

Poetic Diction, Poetic Discourse and the Poetic Register

proceedings of the British Academy, 93.21-93 Poetic Diction, Poetic Discourse and the Poetic Register R. G. G. COLEMAN Summary. A number of distinctive characteristics can be iden- tified in the language used by Latin poets. To start with the lexicon, most of the words commonly cited as instances of poetic diction - ensis; fessus, meare, de, -que. -que etc. - are demonstrably archaic, having been displaced in the prose register. Archaic too are certain grammatical forms found in poetry - e.g. auldi, gen. pl. superum, agier, conticuere - and syntactic constructions like the use of simple cases for pre- I.positional phrases and of infinitives instead of the clausal structures of classical prose. Poets in all languages exploit the linguistic resources of past as well as present, but this facility is especially prominent where, as in Latin, the genre traditions positively encouraged imitatio. Some of the syntactic character- istics are influenced wholly or partly by Greek, as are other ingredients of the poetic register. The classical quantitative metres, derived from Greek, dictated the rhythmic pattern of the Latin words. Greek loan words and especially proper names - Chaoniae, Corydon, Pyrrha, Tempe, Theseus, Zephym etc. -brought exotic tones to the aural texture, often enhanced by Greek case forms. They also brought an allusive richness to their contexts. However, the most impressive charac- teristics after the metre were not dependent on foreign intrusion: the creation of imagery, often as an essential feature of a poetic argument, and the tropes of semantic transfer - metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche - were frequently deployed through common words. In fact no words were too prosaic to appear in even the highest poetic contexts, always assuming their metricality. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

Alliteration-For-Letter-T.Pdf

Alliteration For Letter T Select Download Format: Download Alliteration For Letter T pdf. Download Alliteration For Letter T doc. Confused with scottish asroots catullus of consonance, or to find. Unsplashsomehave the leaves. say Intense alliteration interest adds in theemphasis fleet flown developed deer the by repeating the tongue characters, twister, readythen the for things. a letter Commercial t so that the writing day. Course an alliteration according in oneto transform of your the the sand. type inTurnus every is important clear credit part is of itwords to draw by thefree word printable data ison there a dream is when speech. the verse. Starts Blood with care hitting for thestopping sentence by justin to alliteration and. Similarly for letter to use t is tothe write impact? better Citation to literature info for like letter that t areso apparentlyaware of 5 yougreat. want? Cheap Unsplashwretched and rhymes and repetitionslike with golden goose any tool and Browsersorting letter will appeart is for ain wood. the writing, Filter wordmelodious lists now sounds i accept create and a adtongue slogan twisters sound are snowman sure to yourprintablemy. the inheart? learning Readily to the allowed alliteration in recognising for letter t suchis almost a tool every for kids important? to get started Youth upshe to learns the page. all slots Grows on greener ofwednesday. poetry and Glided example glacier to a acrossletter at will the occur green on was. meaning Naming to repetitionof rhyming of fun your with the a winter.word finderwhen Mind of the you end withremember origin asnames in a frame!of this isNeighbors white fragility are full a clothespin. -

New Latin Grammar

NEW LATIN GRAMMAR BY CHARLES E. BENNETT Goldwin Smith Professor of Latin in Cornell University Quicquid praecipies, esto brevis, ut cito dicta Percipiant animi dociles teneantque fideles: Omne supervacuum pleno de pectore manat. —HORACE, Ars Poetica. COPYRIGHT, 1895; 1908; 1918 BY CHARLES E. BENNETT PREFACE. The present work is a revision of that published in 1908. No radical alterations have been introduced, although a number of minor changes will be noted. I have added an Introduction on the origin and development of the Latin language, which it is hoped will prove interesting and instructive to the more ambitious pupil. At the end of the book will be found an Index to the Sources of the Illustrative Examples cited in the Syntax. C.E.B. ITHACA, NEW YORK, May 4, 1918 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. The present book is a revision of my Latin Grammar originally published in 1895. Wherever greater accuracy or precision of statement seemed possible, I have endeavored to secure this. The rules for syllable division have been changed and made to conform to the prevailing practice of the Romans themselves. In the Perfect Subjunctive Active, the endings -īs, -īmus, -ītis are now marked long. The theory of vowel length before the suffixes -gnus, -gna, -gnum, and also before j, has been discarded. In the Syntax I have recognized a special category of Ablative of Association, and have abandoned the original doctrine as to the force of tenses in the Prohibitive. Apart from the foregoing, only minor and unessential modifications have been introduced. In its main lines the work remains unchanged. -

Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 1

Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 1 The following characters are described in the pages that follow the list. Page Order Alphabetical Order Aeolus 2 Achaemenides 8 Neptune 2 Achates 2 Achates 2 Aeolus 2 Ilioneus 2 Allecto 19 Cupid 2 Amata 17 Iopas 2 Andromache 8 Laocoon 2 Anna 9 Sinon 3 Arruns 22 Coroebus 3 Caieta 13 Priam 4 Camilla 22 Creusa 6 Celaeno 7 Helen 6 Coroebus 3 Celaeno 7 Creusa 6 Harpies 7 Cupid 2 Polydorus 7 Dēiphobus 11 Achaemenides 8 Drances 30 Andromache 8 Euryalus 27 Helenus 8 Evander 24 Anna 9 Harpies 7 Iarbas 10 Helen 6 Palinurus 10 Helenus 8 Dēiphobus 11 Iarbas 10 Marcellus 12 Ilioneus 2 Caieta 13 Iopas 2 Latinus 13 Juturna 31 Lavinia 15 Laocoon 2 Lavinium 15 Latinus 13 Amata 17 Lausus 20 Allecto 19 Lavinia 15 Mezentius 20 Lavinium 15 Lausus 20 Marcellus 12 Camilla 22 Mezentius 20 Arruns 22 Neptune 2 Evander 24 Nisus 27 Nisus 27 Palinurus 10 Euryalus 27 Polydorus 7 Drances 30 Priam 4 Juturna 31 Sinon 2 An outline of the ACL presentation is at the end of the handout. Minor Characters in the Aeneid Page 2 Aeolus – with Juno as minor god, less than Juno (tributary powers), cliens- patronus relationship; Juno as bargainer and what she offers. Both of them as rulers, in contrast with Neptune, Dido, Aeneas, Latinus, Evander, Mezentius, Turnus, Metabus, Ascanius, Acestes. Neptune – contrast as ruler with Aeolus; especially aposiopesis. Note following sympathy and importance of rhetoric and gravitas to control the people. Is the vir Aeneas (bringing civilization), Augustus (bringing order out of civil war), or Cato (actually -

The Poems of Catullus As They Went to the Printer for the first Time, in Venice 400 Years Ago

1.Catullus, Poems 1/12/05 2:52 PM Page 1 INTRODUCTION LIFE AND BACKGROUND We know very little for certain about Catullus himself, and most of that has to be extrapolated from his own work, always a risky procedure, and nowadays with the full weight of critical opinion against it (though this is always mutable, and there are signs of change in the air). On the other hand, we know a great deal about the last century of the Roman Republic, in which his short but intense life was spent, and about many of the public figures, both literary and political, whom he counted among his friends and enemies. Like Byron, whom in ways he resembled, he moved in fashionable circles, was radical without being constructively political, and wrote poetry that gives the overwhelming impression of being generated by the public aªairs, literary fashions, and aristocratic private scandals of the day. How far all these were fictionalized in his poetry we shall never know, but that they were pure invention is unlikely in the extreme: what need to make up stories when there was so much splendid material to hand? Obviously we can’t take what Catullus writes about Caesar or Mamurra at face value, any more than we can By- ron’s portraits of George III and Southey in “The Vision of Judgement,” or Dry- den’s of James II and the Duke of Buckingham in “Absalom and Achitophel.” Yet it would be hard to deny that in every case the poetic version contained more than a grain of truth. -

Efi – Virgil and the World of the Hero

FROM TROY TO ROME: THE WORLD OF THE HERO IN VIRGIL’S AENEID Dr Efi Spentzou Royal Holloway, University of London [email protected] 1 A note on the translation A note on the text: the translation used in this presentation is by Robert Fagles for Penguin Classics. It is modern and vibrant and I hope you enjoy it! To create this free flow feel, and unlike other translations who try to adapt themselves so they are closer to the original line numberings, the lines in Fagles’ translation do not follow closely the lines in the original. So in order to make things easier for any of you who wish to look the text up in other translations or in the Latin text itself, I have given you the original text lines in the parenthesis. 2 Before Virgil… üAeneas mentioned in: Aeneas was only a minor figure in the ü Greek epic Iliad 20.307-8 narratives ü‘And now the might of Aeneas shall be lord over the Trojans and his sons’ sons, and those who are born of their seed hereafter.’ üHymn to Aphrodite 196-8 ü‘You will have a son of your own, who amongst the Trojans will rule, and children descended from him will never lack children themselves. His name will be Aeneas…’ 3 Aeneas: the Roman Achilles? v Aeneas = mythical and historical ◦ A figure more complicated than Achilles, carrying vHomeric hero (fight) Homeric, Hellenistic and v‘So let’s die, let’s rush to the thick Roman traits. of the fighting.’ (Aeneid 2) vHellenistic hero (emotion) v‘And I couldn’t believe I was bringing grief so intense, so painful to you.’ (Aeneas to Dido in Aeneid 6) vRoman hero (leadership) v‘You, who are Roman, recall how to govern mankind with your power.’ (Aeneid 6) 4 Book 1 The temple of Juno vThe strange sight of an ‘old’ and famous war: ◦ Aeneas now looking at ‘his’ ‘Here in this grove, a strange sight met his war from ‘the eyes and calmed his fears for the first time. -

Dr Efi Spentzou, Virgil and the World of the Hero

FROM TROY TO ROME: THE HERO’S JOURNEY IN VIRGIL’S AENEID Dr Efi Spentzou Royal Holloway, University of London [email protected] 1 Fact check about the Aeneid ØMajor epic narrative: a landmark of Latin literature. Probably published in 19BCE (in writing for a decade). ØPlot: journey from Troy to Italy, arrival and war against local tribes. Ø2-in-1 package: An Odyssey (Book 1-6) and an Iliad (Books 7-12) ØTarget: the foundation of Rome as Fate has decided. ØMain protagonist: Aeneas, son of Anchises, cousin of Hector. ØA parallel plot -Aeneas’ journey: from Iliadic and/or Odyssean hero to Roman Leader 2 A note on the translation A note on the text: the translation used in this presentation is by Sarah Ruden for Yale University Press, easily accessible via the usual bookstores. Importantly, it is the first English translation of the Aeneid by a woman. I hope you enjoy it! 3 Before Virgil… Aeneas only mentioned in: Aeneas was only a minor figure in the üIliad 20.307-8 Greek epic ü‘And now the might of Aeneas shall narratives be lord over the Trojans and his sons’ sons, and those who are born of their seed hereafter.’ üHomeric Hymn to Aeneas: the big Aphrodite 196-8 Unknown, a hero ü‘You will have a son of your own, who in the making amongst the Trojans will rule, and children descended from him will never lack children themselves. His name will be Aeneas…’ ◦ Homeric Hymns: celebrations of Greek Gods written in the Homeric style, around the same time as the Homeric epics. -

AP® Latin Teaching the Aeneid

Professional Development AP® Latin Teaching The Aeneid Curriculum Module The College Board The College Board is a mission-driven not-for-profit organization that connects students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the College Board was created to expand access to higher education. Today, the membership association is made up of more than 5,900 of the world’s leading educational institutions and is dedicated to promoting excellence and equity in education. Each year, the College Board helps more than seven million students prepare for a successful transition to college through programs and services in college readiness and college success — including the SAT® and the Advanced Placement Program®. The organization also serves the education community through research and advocacy on behalf of students, educators and schools. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.org. © 2011 The College Board. College Board, Advanced Placement Program, AP, AP Central, SAT, and the acorn logo are registered trademarks of the College Board. All other products and services may be trademarks of their respective owners. Visit the College Board on the Web: www.collegeboard.org. Contents Introduction................................................................................................. 1 Jill Crooker Minor Characters in The Aeneid...........................................................3 Donald Connor Integrating Multiple-Choice Questions into AP® Latin Instruction.................................................................... -

Vergil and the English Poets Columbia University Press Sales Agents

Book .N h Copyright N^ CDRORIGHT DEPOSIT. Columbia Wini\itt0itv STUDIES IN ENGLISH AND COMPARATIVE LITERATURE VERGIL AND THE ENGLISH POETS COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS SALES AGENTS NEW YOltK LEMCKE & BUECHNER 30-32 Eabt 27tu Stueet LONDON HUMPHREY MILFORD Amen Corner, E.G. SHANGHAI EDWARD EVANS & SONS, Ltd. 30 North Szechuen Road VERGIL AND THE ENGLISH POETS BY ELIZABETH NITCHIE, Ph. D. Instructor in English in Goucher Collegb ^^^'^^^ COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS 1919 All rights reserved < Copyright, 1919 By Columbia University Press Printed from type, April, 1919 ^ k7 i9!9 ©CI.A515690 -v- .', ( This Monograph has been approved by the Department of English and Comparative Literature in Columbia University as a contribution to knowledge worthy of publication. A. H. THORNDIKE, Executive Officer PREFACE This book has grown out of a long-standing interest in the classics and a feeling that the connection between the Uterature of Greece and Rome and that of England is too seldom realized and too seldom stressed by the lovers and teachers of both. As Sir Gilbert Murray has said in his recent presidential address to the Classical Association of England, The Religion of a Man of Letters, ^^ Paradise Lost and Prometheus Unbound are . the children of Vergil and Homer, of Aeschylus and Plato. Let us admit that there must of necessity be in all English literature a strain of what one may call vernacular English thought. ... It remains true that from the Renaissance onward, nay, from Chaucer and even from Alfred, the higher and more massive workings of our literature owe more to the Greeks and Romans than to our own un-Romanized ancestors." Vergil has probably exerted more influence upon the literature of England throughout its whole course and in all its branches than any other Roman poet.