Efi – Virgil and the World of the Hero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

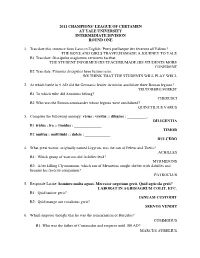

Intermediate Division Round One

2011 CHAMPIONS’ LEAGUE OF CERTAMEN AT YALE UNIVERSITY INTERMEDIATE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Translate this sentence from Latin to English: Pueri puellaeque iter fecerunt ad Yalium? THE BOYS AND GIRLS TRAVELED/MADE A JOURNEY TO YALE B1 Translate: Discipulus magistrum certiorem facebat. THE STUDENT INFORMED HIS TEACHER/MADE HIS STUDENTS MORE CONFIDENT B2 Translate: Putamus discipulos bene lusuros esse. WE THINK THAT THE STUDENTS WILL PLAY WELL 2. At which battle in 9 AD did the Germanic leader Arminius annihilate three Roman legions? TEUTOBERG FOREST B1 To which tribe did Arminius belong? CHERUSCI B2 Who was the Roman commander whose legions were annihilated? QUINCTILIUS VARUS 3. Complete the following analogy: vrus : vrits :: diligns : __________. DLIGENTIA B1 rtus : ra :: timidus : ______________ TIMOR B2 multus : multitd :: dulcis : _____________ DULCD 4. What great warior, originally named Ligyron, was the son of Peleus and Thetis? ACHILLES B1: Which group of warriors did Achilles lead? MYRMIDONS B2: After killing Clytonomous, which son of Menoetius sought shelter with Achilles and became his favorite companion? PATROCLUS 5. Responde Latine: homines multa agunt. Mercator negotium gerit. Quid agricola gerit? LABORAT IN AGRIS/AGRUM COLIT, ETC. B1: Quid ianitor gerit? IANUAM CUSTODIT B2: Quid mango aut venalicius gerit? SERVOS VENDIT 6. Which emperor thought that he was the reincarnation of Hercules? COMMODUS B1. Who was the father of Commodus and emperor until 180 AD? MARCUS AURELIUS B2. What was the name of Commodus’ mistress, believed to have been a Christian? MARCIA 7. Make the phrase “lx t vrits” accusative plural. LCS T VRITTS B1. Make “lcs t vritts” genitive plural. -

Furthest Voices in Virgil's Dido I

FURTHEST VOICES IN VIRGIL’S DIDO I ‘We have to stop somewhere, but we also have to face the fact that any par- ticular stopping-place is therefore our choice, and carries with it ideological implications.’ Don Fowler 1 ‘Magnus est Maro’. I. L. La Cerda 2 Part one Reading Dido – in the Aeneid and beyond – has always been an intensely charged literary and political game. A sensitive, loving woman, Dido offers Aeneas a real alternative to the complex business of setting Rome in motion, and her death shows the enormous price there is to pay in terms of human fulfilment and happiness for the sake of empire building. How more or less sympathetic and straightforward she is seen to be is of course crucial to our perception of Aeneas as epic hero, and to the meaning of the Aeneid as a whole. It is only natural that throughout the 20th century, and into the 21st, critics have over- whelmingly packaged this fascinating character as the archetypical ‘other voice’ to the poem’s teleological (not to say ‘Augustan’) plot. 1 D. P. FOWLER 1997: 25 = 2000: 127-128. 2 LA CERDA: vol. 1, p. 441. Furthest Voices in Virgil’s Dido 61 This comfortable opposition rests to a significant extent on a one- sided reading of Dido’s emotional intricacies. Already ancient poets and readers, from Ovid to the Christians, vigorously edited Virgil’s Dido to produce their own challenge to his epic. Building upon Heinze’s influ- ential treatment, modern critics have favoured a comparable approach: current readings emphasize the image of a loving and forlorn heroine whose short outbursts of rage and fury are evanescent – and justified. -

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars. -

1996 Njcl Certamen Round A1 (Revised)

1996 NJCL CERTAMEN ROUND A1 (REVISED) 1. Who immortalized the wife of Quintus Caecilius Metellus as Lesbia in his poetry? (GAIUS VALERIUS) CATULLUS What was probably the real name of Lesbia? CLODIA What orator fiercely attacked Clodia in his Pro Caelio? (MARCUS TULLIUS) CICERO 2. According to Hesiod, who was the first born of Cronus and Rhea? HESTIA Who was the second born? DEMETER Who was the fifth born? POSEIDON 3. Name the twin brothers who fought in their mother's womb. PROETUS & ACRISIUS Whom did Proetus marry? ANTIA (ANTEIA) (STHENEBOEA) With what hero did Antia fall in love? BELLEROPHON 4. Give the comparative and superlative forms of mult§ PLâRS, PLâRIM¦ ...of prÇ. PRIOR, PR¦MUS ...of hebes. HEBETIOR, HEBETISSIMUS 5. LegÇ means “I collect.” What does lectitÇ mean? (I) COLLECT OFTEN, EAGERLY Sitis means “thirst.” What does the verb sitiÇ mean? (I) AM THIRSTY / THIRST CantÇ means “I sing.” What does cantillÇ mean? (I) CHIRP, WARBLE, HUM, SING LOW 6. Differentiate in meaning between p~vÇ and paveÇ. P}VÆ -- PEACOCK PAVEÆ -- (I) FEAR, TREMBLE Differentiate in meaning between cavÇ and caveÇ. CAVÆ -- I HOLLOW OUT CAVEÆ -- I TAKE HEED, BEWARE Differentiate in meaning between modo (must pronounce with short “o”) and madeÇ. MODO -- ONLY, MERELY, BUT, JUST, IMMEDIATELY, PROVIDED THAT MADEÆ -- I AM WET, DRUNK Page 1 -- A1 7. What two words combine to form the Latin verb malÇ? MAGIS & VOLÆ What does malÇ mean? PREFER M~la is a contracted form of maxilla. What is a m~la? CHEEK, JAW 8. Which of the emperors of AD 193 executed the assassins of Commodus? DIDIUS JULIANUS How had Julianus gained imperial power? BOUGHT THE THRONE AT AN AUCTION (HELD BY THE PRAETORIANS) Whom had the Praetorians murdered after his reign of 87 days? PERTINAX 9. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

Lunar References in Virgil's Aeneid

Graeco-Latina Brunensia 24 / 2019 / 1 https://doi.org/10.5817/GLB2019-1-5 Alma Phoebe: Lunar References in Virgil’s Aeneid Lee M. Fratantuono (Ohio Wesleyan University, Delaware) Abstract The moon and lunar phenomena are frequently referenced in Virgil’s Aeneid. Close study of these allusions reveals that the poet employs lunar imagery as a key element in his depiction of the characters of both the Carthaginian Dido and the Volscian Camilla, in particular the de- ČLÁNKY / ARTICLES liberately crafted juxtaposition between the two women. Keywords Virgil; Moon; Luna; Dido; Camilla 61 Lee M. Fratantuono Alma Phoebe: Lunar References in Virgil’s Aeneid The moon serves as astronomical witness to a number of key events in Virgil’s Aeneid.1 The present study will seek to explicate the various references to the moon in the text of the epic (including mentions of the goddess Luna or Phoebe), with a view to illustrating how Virgil employs lunar imagery to significant effect in his poem, in particular in delin- eating the contrast between the opposing pairs Venus/Dido and Diana/Camilla, and as part of his pervasive concern with identifying the relationship between Troy and Rome.2 Near the close of the first book of the epic, the “wandering moon” is cited as the first of the subjects of the song of Dido’s bard Iopas (A. I, 742 hic canit errantem lunam solisque labores).3 The passage echoes similar languages in the song of Silenus from the sixth eclogue (E. VI, 64 tum canit, errantem Permessi ad flumina Gallum),4 where one of the Muses and the divine shepherd Linus rise to give honor to the poet Gallus as he wanders by the Permessus. -

A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos

INSTITUTIONEN FÖR SPRÅK OCH LITTERATURER DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos SARA EHRLING QuickTime och en -dekomprimerare krävs för att kunna se bilden. SARA EHRLING DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM INSTITUTIONEN FÖR SPRÅK OCH LITTERATURER DE INCONEXIS CONTINUUM A Study of the Late Antique Latin Wedding Centos SARA EHRLING Avhandling för filosofie doktorsexamen i latin, Göteborgs universitet 2011-05-28 Disputationsupplaga Sara Ehrling 2011 ISBN: 978–91–628–8311–9 http://hdl.handle.net/2077/24990 Distribution: Institutionen för språk och litteraturer, Göteborgs universitet, Box 200, 405 30 Göteborg Acknowledgements Due to diverse turns of life, this work has followed me for several years, and I am now happy for having been able to finish it. This would not have been possible without the last years’ patient support and direction of my supervisor Professor Gunhild Vidén at the Department of Languages and Literatures. Despite her full agendas, Gunhild has always found time to read and comment on my work; in her criticism, she has in a remarkable way combined a sharp intellect with deep knowledge and sound common sense. She has also always been a good listener. For this, and for numerous other things, I admire and am deeply grateful to Gunhild. My secondary supervisor, Professor Mats Malm at the Department of Literature, History of Ideas, and Religion, has guided me with insight through the vast field of literary criticism; my discussions with him have helped me correct many mistakes and improve important lines of reasoning. -

Virgil's Pier Group

Virgil’s Pier Group In this paper I argue that the ship race of Aeneid 5 presents a metapoetic commentary whereby Virgil re-validates heroic epic and announces the principal intertexts of his middle triad. The games as a whole are rooted in transparent allusion to Iliad 23 and have, accordingly, drawn somewhat less critical attention than books 4 and 6. For Heinze (121-36), the agonistic scenes exemplify Virgil’s artistic principles for reshaping Homeric material. Similarly, Otis (41- 61) emphasized Virgilian characterization. Putnam (64-104) reads the games in conjunction with the Palinurus episode as a reflection on heroic sacrifice. Galinsky has emphasized the degree to which the games are interwoven with themes and diction in both book 5 and the poem as a whole. Harris, Briggs, and Feldherr have explored historical elements and Augustan political themes within the games. Farrell attempts to bring synthesis to these views by reading the games through a lens of parenthood themes. A critical observation remains missing. Water and nautical imagery are well-established metaphors for poetry and poiesis. The association is attested as early as Pindar (e.g. P. 10.51-4). In regard to neoteric and Augustan poetics, it is sufficient to recall the prominence of water in Callimachus (Ap. 105-113). This same topos lies at the foundation of Catullus 64 and appears within both the Georgics and Horace’s Odes (cf. Harrison). The agones of Aeneid 5 would be a natural moment for such motifs. Virgil introduces all four ships as equals (114). Nevertheless, the Chimaera is conspicuous for its bulk and its three-fold oars (118-20). -

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood

SUMMER 2016 HONORS LATIN III GRADE 11: Title: Roman Blood: A Novel of Ancient Rome Author: Steven Saylor Publisher: St. Martin’s Minotaur Year: 2000 ISBN: 9780312972967 You will be creating a magazine based on this novel. Be creative. Everything about your magazine should be centered around the theme of the novel. Your magazine must contain the following: Cover Table of Contents One: Crossword puzzle OR Word search OR Cryptogram At least 6 (six) news articles which may consist of character interviews, background on the time period, slave/master relationship, Roman law, etc. It is not necessary to interview Saylor. One of the following: horoscopes (relevant to the novel), cartoons (relevant to the novel), recipes (relevant to the novel), want ads (relevant to the novel), general advertisements for products/services (relevant to the novel). There must be no “white/blank” space in the magazine. It must be laid out and must look like a magazine and not just pages stapled together. This must be typed and neatly done. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. Due date: September 1, 2016. Thank you. SUMMER 2016 LATIN II GRADE 10: Amsco Workbook: Work on the review sections after verbs, nouns and adjectives. Complete all mastery exercises on pp. 36-39, 59-61, 64-66, 92-95, 102-104. Please be sure to study all relevant vocab in these mastery exercises. Due date is first day of school in August. PLEASE NOTE: You will need $25 for membership in the Classical organizations and for participation in three national exams. -

The Articulation of Space in Shakespeare's King Lear And

“Where am I now?”: The Articulation of Space in Shakespeare’s King Lear and Marlowe’s Dido, Queen of Carthage Along with The Massacre at Paris, Dido, Queen of Carthage has traditionally been one of the more neglected plays of Marlowe’s oeuvre. Apparently written during the playwright’s university years (quite possibly with the help of Thomas Nashe),1 and retelling as it does the events of Books One and Four of Virgil’s Aeneid, Dido has often been treated as closer to an academic exercise in dramatic translation than a play that can stand alongside the more universally acknowledged achievements of Marlowe’s career. Despite this, readings of the play conducted since the mid-1990s have shown it to be considerably more complex than previously acknowledged. Astute new historicist and postcolonial readings have shown that the play simultaneously engages in and interrogates the legitimisation of colonial power through association with mytho-historical antecedents. At a time when Elizabethan England was attempting to establish an intellectual framework for its initial forays into colonial expansion in Ireland and the New World, Marlowe’s play re-imagines a formative moment in the Roman empire’s mythical foundation by adapting a section of an epic Roman poem that was itself a legitimising tool for the first emperor, Augustus.2 In the play, Troy is a site which generates legitimacy; it is made unambiguously clear that the city in Italy which Aeneas will The definitive version of this article is published here: Duxfield, Andrew, “‘Were am I now?’: The Articulation of Space in Shakespeare’s King Lear and Marlowe’s Dido, Queen of Carthage’, Cahiers Élisabéthains 88 (2015), 81–93, DOI: 10.7227/CE.88.1.6 1 For an account of the scholarly debate surrounding the extent of Nashe’s involvement in the writing of the play, and a rejection of the tendency to conceive of Dido as a university play, see Martin Wiggins, “When did Marlowe Write Dido, Queen of Carthage?”, The Review of English Studies 59.241 (2008), 521-41, 524-6. -

Between the Commemorative Games and the Descent to the Underworld

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Between the commemorative games and the descent to the Underworld in Books 5 and 6 of Vergil’s Aeneid: a study of structure and narrative technique in the transition https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40202/ Version: Full Version Citation: Powell„ David John (2017) Between the commemorative games and the descent to the Underworld in Books 5 and 6 of Vergil’s Aeneid: a study of structure and narrative technique in the transition. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Between the commemorative games and the descent to the Underworld in Books 5 and 6 of Vergil’s Aeneid: a study of structure and narrative technique in the transition Thesis submitted in September 2016 by: David John Powell awarded the degree of Master of Philosophy February 2017 Powell, D J September 2016 Declaration I hereby certify that the work presented in this thesis is my own work. …………………………………….. David John Powell ***** DEDICATIO Hunc librum dedico: et memoriae mulieris amatae Mariae et filio dilecto Antonio. Acknowledgments I wish to thank my supervisor, Professor Catharine Edwards, for her prudent suggestions throughout. Also my son, Anthony, and daughter-in-in-law, Julia, both Cambridge classics graduates, for their consistent encouragement. Any and all shortcomings are my own. 2 Powell, D J September 2016 Abstract Book 5 of Vergil’s Aeneid is known for the games commemorating the first anniversary of Anchises’ death; Book 6 for Aeneas’ visit to the Underworld. -

ORIGINS of ROWING • Transportation, Warfare, Recreation� • Development in Ancient Egypt� • Earliest Recreational Reference: Funerary Inscriptions of Amenhotep, C

ORIGINS OF ROWING • Transportation, Warfare, Recreation! • Development in Ancient Egypt! • Earliest recreational reference: funerary inscriptions of Amenhotep, c. 1400 BCE! • Bronze Age fresco from the island of Thera (now Santorini) well- preserved by volcanic eruption, c. 1600 BCE: ! • Trojan War c. 1200 BCE! • Classical Greece, c. 5th century BCE! THE TRIREME THE TRIREME • Oared warships; 170 rowers arranged in three banks of oars on each side; additional 30 on deck! • The name: triremis/trieres • Predecessors: Pentekonter, Bireme! • Phoenician invention (likely), adopted by the Greeks! • Long (~40m) and narrow (~6m); made of lightwood with bronze ram on prow. Oars 13-14ft long. ! • Extremely expensive and labor-intensive to construct, maintain! • All space used for rowers – cramped, no room for supplies; had to travel near shore and be carried out of water overnight ! • Could likely travel about 8 knots – close to 2:00/500m split!! • Light, agile, fast, maneuverable (provided the rowers were skilled)! • “Glorified racing-eight cum waterborne guided missile.” ! TRIREME WARFARE • Simple tactic: ramming ! • Crews must row fast enough to ram prow into enemy ship, disabling it! • Must then quickly row back out ! • Ability to turn quickly critical for attack and evasion! • Used combination of oars and sails for travel, but during actual battles ships were powered by rowers alone! • Most naval battles fought at dawn with calm seas for optimal working of the oars ! • All this requires highly-trained, highly-skilled rowers– you could not outflank