The Theater in Indianapolis Before 1880

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barretto: (--- ) Supported by (--- ) :0 Andmr

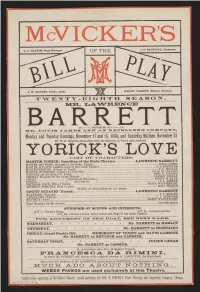

McVICKER'S L. L. SHARPE, Stage Manager. BILL OF THEPLAY C. S. REDFIELD, Treasurer. J. H. ROGERS, Scenic Artist. HENRY DOEHNE, Musical Director. T WENTY-EIGHTH SEASON. MR. LAWRENCE BARRETTO: (--- ) SUPPORTED BY (--- ) :0 ANDMR. LOUISJAMES AN EXCELLENT COMPAN Y. Monday and TuesdayEvenings, November 17 and 18, 1884, and Saturday Matinee, November 22 Mr. W. D. Howell's adaptationfrom the Spanish,in ThreeActs, entitled YORICK'S LOVE CAST OF CHARACTERS: MASTER YORICK, Comedian of the Globe Theatre LAWRENCE BARRETT MASTER HEYWOOD, Manager of the Globe Theatre LOUIS JAMES MASTER WALTON, LeadingActor of the GlobeTheatre S. E. SPRINGER MASTEREDMUND, Protege of Yorick F. C. MOSLEY MASTER WOODFORD, Authorof a NewPlay CHAS M. COLLINS GREGORY, an old servantof YorickBEN G.ROGERS THOMAS, Prompter of the Globe Theatre ALBERT RIDDLE PHILIP } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { PERCY WINTER TOBIAS } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { J. L. FINNEY MISTRESS ALICE, Wife of Yorick } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { MARIE WAINRIGHT MISTRESS DOROTHY, Maid to Alice } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { ROSA FRANCE CHANGE OF CHARACTERS IN ACT THIRD. COUNT OCTAVIO (Yorick) LAWRENCE BARRETT MANFREDO (Edmund) F. C. MOSLEY LANDOLPHO (Walton) S. E. SPRINGER BEATRICE (Alice) MARIE WAINWRIGHT Stage Manager for Mr. Barrett OLIVER DOUD SYNOPSIS OF SCENES AND INCIDENTS: ACT I.-Yorick's Home. ACT II.-Yorick's Garden. ACTIII.—Scenes 1 and 2—Green Room and Stage of old GlobeTheatre. FOR ARGUMENT OF THE PLAY, SEE NEXT PAGE. WEDNESDAY, Mr. BARRETT as HAMLET THURSDAY, Mr. BARRETT as RICHELIEU FRIDAY, Grand Double Bill, MERCHANTOF VENICE and DAVID GARRICK Mr. BARRETT- as SHYLOCK and GARRICK. SATURDAYNIGHT, JULIUS CAESAR Mr. -

15/7/39 Liberal Arts and Sciences Department of English Charles H

The materials listed in this document are available for research at the University of Record Series Number Illinois Archives. For more information, email [email protected] or search http://www.library.illinois.edu/archives/archon for the record series number. 15/7/39 Liberal Arts and Sciences Department of English Charles H. Shattuck Papers, 1929, 1937-92 CONTENTS Box Correspondence, A-Z, 1944-61 1 Correspondence, A-Z, 1961-92 2-6 Subject File, A-W, 1929, 1946-91 6-10 Accent File, A-W, 1942-79 10 Shattuck Promptbooks, 1942-77 10-14 Playbills, 1913-88 14-15 Publications & Reviews, 1938-86 15-16 Research Notes & Correspondence, 1937-92 Macready & Booth 16-17 Shakespeare Promptbooks 17-21 Shakespeare on the American Stage 21-22 Theatre and Brecht 23 Posters & Slides 24 Box 1: Correspondence, 1944-61 A, 1946-58 Adams, John C. 1945-58, 1960 B, 1947-60 Brecht, Bertolt, 1955 C, 1947-60 D, 1946-59 E, 1946-60 Engle, Paul, 1946-56 F, 1945-60 Ford Foundation, W. McNeil Lowry, 1958-59 G, 1945-60 Gregor, Arthur, 1951-54 H, 1943-60 Harrison, G.B., 1957-58 Hewitt, Barnard, 1947-56 Hanson, Philip, 1951-57 I-K, 1942, 1947-61 L, 1946-60 M, 1944-61 15/7/39 2 N-O, 1949-60 P, 1949-60 Q, 1958-60 R, 1944-64 Sa-Sh, 1948-61 Sl-Sy, 1943-60 Stoddard, Margaret, 1954-55 Swanson, John Wesley, 1946-59 T, 1946-60 U-V, 1948-61 Vassar College, 1948-49 W, 1946-60 Wallace, Karl, 1947-49 X-Z, 1953-59 Box 2: Correspondence, 1961-92 A, 1961-92 Abou-Saif, Laila, 1964-69, 1978 Adams, John C., 1961-85 Andrews, John F., 1976-91 Andrews, Kenneth R., 1963-91 Archer, Stephen, -

Broadside Read- a Brief Chronology of Major Events in Trous Failure

NEWSLETTER OF THE THEATRE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Volume 17, Number 1/Volume 17, Number 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE Summer/Fa111989 EXHIBITION SURVEYS MANHATTAN'S EARLY THEATRE HISTORY L An exhibition spotlighting three early New York theatres was on view in the Main I Gallery of The New York Public Library at Lincoln Center from February 13, 1990 through March 31, 1990. Focusing on the Park Theatre on Park Row, Niblo's Garden on Broadway and Prince Street, and Wal- lack's, later called the Star, on Broadway and 13th Street, the exhibition attempted to show, through the use of maps, photo- graphic blowups, programs and posters, the richness of the developing New York theatre scene as it moved northward from lower Manhattan. The Park Theatre has been called "the first important theatre in the United States." It opened on January 29, 1798, across from the Commons (the Commons is now City Hall Park-City Hall was built in 1811). The opening production, As You Like It, was presented with some of the fin- est scenery ever seen. The theatre itself, which could accommodate almost 2,000, was most favorably reviewed. It was one of the most substantial buildings erected in the city to that date- the size of the stage was a source of amazement to both cast and audience. In the early nineteenth century, to increase ticket sales, manager Stephen Price introduced the "star sys- tem" (the importation of famous English stars). This kept attendance high but to some extent discouraged the growth of in- digenous talent. In its later days the Park was home to a fine company, which, in addition to performing the classics, pre- sented the work of the emerging American playwrights. -

Appendix: Famous Actors/ Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom's Cabin

A p p e n d i x : F a m o u s A c t o r s / Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom’s Cabin Uncle Tom Ophelia Otis Skinner Mrs. John Gilbert John Glibert Mrs. Charles Walcot Charles Walcott Louisa Eldridge Wilton Lackaye Annie Yeamans David Belasco Charles R. Thorne Sr.Cassy Louis James Lawrence Barrett Emily Rigl Frank Mayo Jennie Carroll John McCullough Howard Kyle Denman Thompson J. H. Stoddard DeWolf Hopper Gumption Cute George Harris Joseph Jefferson William Harcourt John T. Raymond Marks St. Clare John Sleeper Clarke W. J. Ferguson L. R. Stockwell Felix Morris Eva Topsy Mary McVicker Lotta Crabtree Minnie Maddern Fiske Jennie Yeamans Maude Adams Maude Raymond Mary Pickford Fred Stone Effie Shannon 1 Mrs. Charles R. Thorne Sr. Bijou Heron Annie Pixley Continued 230 Appendix Appendix Continued Effie Ellsler Mrs. John Wood Annie Russell Laurette Taylor May West Fay Bainter Eva Topsy Madge Kendall Molly Picon Billie Burke Fanny Herring Deacon Perry Marie St. Clare W. J. LeMoyne Mrs. Thomas Jefferson Little Harry George Shelby Fanny Herring F. F. Mackay Frank Drew Charles R. Thorne Jr. Rachel Booth C. Leslie Allen Simon Legree Phineas Fletcher Barton Hill William Davidge Edwin Adams Charles Wheatleigh Lewis Morrison Frank Mordaunt Frank Losee Odell Williams John L. Sullivan William A. Mestayer Eliza Chloe Agnes Booth Ida Vernon Henrietta Crosman Lucille La Verne Mrs. Frank Chanfrau Nellie Holbrook N o t e s P R E F A C E 1 . George Howard, Eva to Her Papa , Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture . http://utc.iath.virginia.edu {*}. -

GREAT ACTORS WHOSE FAME IS LINKED with the POET's the Second Wallack's Theatr from 18(1 T Some Traphlo Force the Working of Tk Kw U82

THE SUN, SUNDAY, APRIL 16, 1916. GREAT ACTORS WHOSE FAME IS LINKED WITH THE POET'S the second Wallack's Theatr from 18(1 t some traphlo force the working of tk kW U82. In 1882 ho opened the third and last of taste tn literature. Edwin Booth Wallack's Theatre at Thirtieth street ana The repute that Shakespeare aoaaJsM H Broadway, which he conducted with great his lifetime, though It was rarely deflMa with subtlety, BOOTH wtw the second Bon of liberality and artistic success, although was In spirit all that J EDWIN Brutus llooth, tho celebrated tho financial results were less satisfactory. dlclous admirers could desire. The ary nctor, and was horn In Ho himself was a popular actor, espe- JofinTfacxuUouQt estimate was authorltatltoly llelalr, Marylaihl, November IS, cially in comedy. Ills greatest successes ummed up tn the epitaph which wm In- wore on Htratford-on-Avo- 1WI. Ills Mrt regular appearance un tho as Charles Burfaca, aa Benedick and scribed his monument In n stago wns At Uic Boston Museum In Sep- especially as JJIHot Urey In his own play, ohurch soon after his death. In that "Kn.scdalc," comedy inscription tember. 1849, with his father In "Hlchurd and in similar light and ha was hailed as the equal of Members of the thentrlcnl pretension, romantic parts, for which his fascinating great l.eroes of classical antiquity of Nes- lilt" manner person welt fitted In who held the elder Booth's noting In great and handsome tor wisdom, of Socrates li genius, of reverence, seemed to agree lilm. -

22760·1 PHOTOGRAPH Surchedlhc Ainley, Henry, 1879-1945 O",..N 2291 Photograph of Ainley As Hamlet, Dol

-, Gilt Photographs Model theatre based on plans of J ,C'IAdams 6 photogra:,hs of theatre and stage. Gift of Charles Shattuck, 3.3.44 JUN 30 '01' 22760·1 PHOTOGRAPH surchedlhc Ainley, Henry, 1879-1945 o",..n 2291 Photograph of Ainley as Hamlet, Dol. 10-14-86 signed and inscribed. To Tristan Rawson. so=Smith & Fawke 1930. orr.. q 9- 24-86 sel by en Price £2 Rec. by Roc'd1f2. 'fL Iv Ae<'dl-87 lhc LC No. Gilt Aldridge Photograph of Garrick Club portrait Gift of Willard Connel,y 1.17.38 .- Photo raph "All the 110 rId '5 a Stage". Photograph of a painting by Samuel de rilde, Depicting a scene from the playas iven at Drury Lane Theatre on i..arch 18th, 1803. 'r. ~uick as Sir Gilbert Pumpkin and Mrs. F. A. Henry as Kitty Sprightly in Gift of B. F. Stevens & Brown, .Ltd. June 13, 1946. Photographs Allen, Viola Photographs of ss Allen In Shakespearian roles: As Desdemona 1 photograph As Lady lJacbeth 15 photographs As Mistress Ford 2 photographs Scenes from CYD'.beline 5 photographs Scenes from Twelfth Night 6 photographs Scenes from Winter's Tale 5 phntographs In non-5hekespearian roles 7 photographs Gift of Charles W. Allen, June 23, 1948. American Shakespeare Festival TLeatre S.are:h.d and Academy, Stratford, Connecticut. Order n.o photographs from the 1969 15th) Oate season••• frp~ the productions of ll"",let Source JGM and Henry 2:.. 2 photos. orrer Price gift Rec. by Rec'd 4- 26-73 Acc'd • '" \ LC No. Photograph Barrett, La'in'ence aI. -

From Richard III to Rex I

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard From Richard III to Rex I Tower of London was a 1939 movie starring Basil Rathbone as the future Richard III of England, with Boris Karloff as the fictional executioner Mord. Vincent Price appeared as George, Duke of Clarence, in this quasi-horror historical drama. In 1962 Tower of London was remade by Roger Corman, this time starring Vincent Price in the lead role as Richard III. Francis Ford Coppola worked on the movie as dialogue director. Vincent Price, Jr. (May 27, 1911 – October 25, 1993), the American actor with the perfect voice for horror movies, grew up in Saint Louis, Missouri, in a well-to-do family whose wealth was made possible years earlier when his grandfather invented “Dr. Price’s Baking Powder”. “The Prices loved to travel”, wrote the actor’s daughter, Victoria Price. “Marguerite and Vincent Sr. had been to Europe, and as their children grew older, whenever they could the couple took shorter trips to interesting cities such as New Orleans … returning with ‘artistic’ souvenirs”. From his travels at home and abroad, young Vincent Price acquired a passion for art and, along with an art history major at Yale University, an interest in the theatre. Despite his long career performing in films of the macabre, Price began as a character actor. He gave a memorable performance in the film Laura in 1944. In the 1950s, viewers enjoyed wearing 3-D glasses to watch Price in House of Wax and thrilled to The Fly (1958) and Return of the Fly (1959). -

Of Allah" Which

THE OMAHA SUNDAY BKK: FKlHU'AHY 1, 1914 9- -13 FAMOUS ACTRESS OF TWENTY- - YEARS AGO M RRANDEIS THEATER SFIVE CRAWFORD, PHlLLEY G ZEHRUNG, Mgra. M(SVV 1 I Toir8 TIKBDAV J TODAY Tuesday THE MUSIC OKfcAlVf A by OKXK BTIlATTOX.POItTHIt Popular Pricod Matinees -:- - 25c-50- c Iftl nnv ami v i nuc 1 r-a- s ilnur I u - 1. tivi 7ui uatiucci PCI " vhi vii ccddii uuivu u mi inui. aim mum IDA WESTON RAE IN THE MORAL AND UPLIFTIN8 DRAMA AS YE SOW Tr I Mat. 25c and 50c Night 25c, 35c, 50c, 75c FOUR N8GHTS Feb. S, 9, 10, 11 Wed. Mat. OMVIIIt MOHOSCO 1'roscnts tho (Jivntcst Comedy lilt of UioDo-nrt-o Eli 0' MY HEART Ity J. HAHTLRV MAXXI2KS (Lnurt'tte Taylor' Vcrjicttinl New York Success) One Oay 3,iy--Fe- b. 12, fthiinse and Night Wim.iam Morris akxounckb HARRY LAUDER Anil His Compnny of International Artists Engaged In His FIRST ROUKll.THIMVORM) TOUR Price Mat. 50c to $1.50; Night 50c to $2 TWO NSGhTS-Fc- B. 13 - 14, Saturday Matins WILLIAM A. RRADY OKFKRS BOUGHT and PAID FOR Tho Great Nqw York nnd London Success by doorgq Broadhurct ONE WEEK CCD , Ifi MATINEES 4 COE Sunday TIM 13 Wii. mi Saturrfty THK WORLDS GRKATKST DRAMATIO SPKCTACLK The GARDEN 4 AmiPros -- At Ae o&pimm At, the ORPHSCM HE recurrence Jn print of the tors who had played with her Tatd For" at tho Brandels February namo of Mary Anderson is days when alio was "Our Mary." and U for three performances. -

Performing Shakespeare in the Age of Empire

PERFORMING SHAKESPEARE IN THE AGE OF EMPIRE RICHARD FOULKES PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CBRU,UK West th Street, New York, NY -, USA Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC , Australia Ruiz de Alarc´on , Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town , South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Richard Foulkes Thisbook isin copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville Monotype /. pt. System LATEX ε [TB] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Foulkes, Richard. Performing Shakespeare in the age of empire / Richard Foulkes. p. cm. Includesbibliographical referencesand index. ISBN . Shakespeare, William, – – Stage history – –. Shakespeare, William, – – Stage history – Great Britain. Shakespeare, William, – – Stage history – North America. Shakespeare, William, – – Stage history – Europe. Theater – Great Britain – History – th century. Theater – Great Britain – History – th century. Theater – History – th century. Theater – History – th century. I. Title. PR.F . –dc ISBN hardback Contents List of illustrations page viii Acknowledgements -

The Shakespeare Tradition in Philadelphia. 161

The Shakespeare Tradition in Philadelphia. 161 THE SHAKESPEARE TRADITION IN PHILADELPHIA. BY JOSEPH JACKSON. (Read before the Contemporary Club, March 13, 1916.) About twenty-five years ago Walt Whitman told his Boswell, Horace Traubel, that Shakespeare would be laid on the upper shelf, but I have a suspicion that the iiGood Gray Poet" unintentionally deceived his liter- ary executor, for there is no evidence that the drama- tist is passe, though he may have become more classic. The fact is, the city fathers tried to lay the bard on the shelf the first time he showed his head, and they did succeed in driving him out of town. Fortunately, Philadelphia in numerous ways has made amends for its hasty conduct in 1749. In driving away the com- pany of actors who strove to enlighten the Quaker City, the Council very nearly prevented this city from enjoy- ing the distinction of being the first on this continent to witness a Shakespearean play. The theatrical histories give the credit to New York, but the evidence, or rather the inference, is that it was in Philadelphia, and not in New York, that Eichard IH received its initial presentation in America. We know from the journals of the Common Council, that in the early winter of 1749, William Allen, the Becorder of the City—he of the splendid turn-out- four black horses and an imported English coachman- acquainted the Council that certain persons had taken it upon themselves to act plays, and as he was in- formed, to have made a practice thereof. -

The Life and Art of Edwin Booth and His Contemporaries

THE LIFE AND ART OF EDWIN BOOTH AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES EDWIN BOOTH As Hamlet. &/fti <7^F?^sr<) jf^jQe^L^ fl&^rrsyb^^ *< Stye Hife atti Art of IHtomt Imrtlf and I|t3 (Entttemjrorarips wtsW* 19 By Brander Matthews and Laurence Hutton J* Yf/jt&n ifUusttratefc ^^^@^<?^s^>^^^^^^ L C PAGE- 8 COMPANY ""w^W/ BOSTON j» PUBLISHERS Copyright, 1886 By O. M. Dunham All rights reserved Fifth Impression, June, 1907 COLONIAL PRESS Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds &* Co. Boston, U.S.A. CONTENTS PAGE Miss Mary Anderson . William L. Keese • I Mr. and Mrs. Bancroft William Archer , . 19 Mr. Lawrence Barrett William M. Laffan . 37 Mr. Edwin Booth. Lawrence Barrett . 55 Mr. and Mrs. Dion Boucicault Benjamin Ellis Martin 77 Mr. J. S. Clarke . Edw, Hamilton Bell . 95 Mr. and Mrs. Florence Laurence Hutton . 113 Mr. Henry Irving J. Ranken Towse . 131 Mr. Joseph Jefferson . H C. Bunner . .153 Mr. and Mrs. Kendal . William Archer . .175 Mme. Modjeska . Jeannette Leonard Gilder 193 Miss Clara Morris Clinton Stuart . .211 Mr. John T. Raymond. George H. Jessop . .229 Miss Ellen Terry Geo. Edgar Montgomery 247 Mr. J. L. Toole . Walter Hen ies Pollock 265 Mr. Lester Wallack . William Winter . .283 Index • • . 301 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE Edwin Booth as Hamlet .... Frontispiece Mary Anderson as Galatea in " Pygmalion and Galatea" . 14 " " Lawrence Barrett as Cassius in Julius Caesar . 39 Edwin Booth 57 Dion Boucicault 79 Agnes R. Boucicault 86 W. J. Florence 115 Mrs. W. J. Florence 126 Henry Irving 133 Henry Irving as Mathias in "The Bells" . 136 Joseph Jefferson as Bob Acres in "The Rivals". -

William Shakespeare and the American People: a Study in Cultural Transformation Author(S): Lawrence W

William Shakespeare and the American People: A Study in Cultural Transformation Author(s): Lawrence W. Levine Source: The American Historical Review, Vol. 89, No. 1 (Feb., 1984), pp. 34-66 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1855917 . Accessed: 17/03/2014 16:43 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Oxford University Press and American Historical Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Historical Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Mon, 17 Mar 2014 16:43:19 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions WilliamShakespeare and the AmericanPeople: A Study in Cultural Transformation LAWRENCE W. LEVINE THE HUMOR OF A PEOPLE AFFORDS IMPORTANT INSIGHTS into the nature of their culture.Thus Mark Twain's treatmentof Shakespearein his novelHuckleberry Finn helps us place the Elizabethanplaywright in nineteenth-centuryAmerican culture. Shortlyafter the two rogues,who pass themselvesoff as a duke and a king,invade the raftof Huck and Jim,they decide to raise funds by performingscenes from Shakespeare's Romeoand Julietand RichardIII.