"Othello.". Janet Barton Carroll Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1968.10.16.Pdf (8.470Mb)

_ Flt h ? - The Salis bur1 Stat'e ... occer ~(' - R cord _ ow .. Outten's 3-1-2 A nswers" Png 3! foJ:xXXVIII - NO. 2 OCTOBER 16, 196 FAI .Y '' TO y PL 0 s C. l\lr. \Vilson haron Leo nard, a senior, as Eliza Doolittle; John O'Ma y, also a sen io r, as Henry Higgins; Ike F eath er, a sophomore, as Colonel Pick in g is a n 1 I rly eli ng ; Frank Parks, a junior, as man who a ·ls Ml ll1 <' h ::u·acl t ' F'reddy Eynsford-Hill ; and Tom I al11. n c I lwC'r n J·~liza :mcl Hig Davis, a freshman, as Alfred P . g in s. Hr is the •pi Lom of lhc old Doolittle. gng ll sh grnllc•ma n." Fl"anlc Parks, who plays Fr ddy Eynsfor l-Hill, has b n in lh SSC proclu lions of arni v:tl and Com Alexander .Scourby Presents Program (• lly of J~rron; and in lh student produ lion Phoenix Too F r - A noted actor of stage, scr een, <1111·111. He a lso di!" • lr cl L ('t 'l'hrrl' radio and television came to lk 1"::trc·(• las l y 111·. cscl"ibin g I hr alisbury State College on Thurs r; hara :ler of l•' n ·clcl y, h<' said , day, October 3, 1968, in H olloway "F1·rclcl y iH an a1" islocn1li ·. s liff Hall Auditorium when Alexander 'CJli a 1· young 111 :1_11 wilh a l finilc courby presented " Walt Whit cl a mpne>ss b hincl llw cars. -

Program Design: Tim Osborne

MATC Offi cers President: Beth Osborne, Florida State University 1st Vice President: Chris Woodworth, Hobart and William Smith Colleges 40th 2nd Vice President/Conference Coordinator: Shawna Mefferd Kelty, ANNUAL College at Plattsburgh, Mid-America Theatre Conference State University of New York Associate Conference Coordinator: March 7-10, 2019 La Donna Forsgren, Cleveland Marriott Downtown University of Notre Dame at Key Tower Cleveland, Ohio Secretary: Jennifer Goff, Virginia Tech University Treasurer: Brian Cook, Invention University of Alaska, Anchorage Theatre History Studies, the Journal of the Mid-America Theatre Conference Editor: Sara Freeman, Conference Keynote Speakers: University of Puget Sound Tami Dixon and Jeffrey Book Review Editor: Robert B. Shimko, Carpenter, University of Houston Co-founders Bricolage Production Company Theatre/Practice: The Online Journal of the Practice/Production Symposium of MATC Theatre History Symposium Editor: Jennifer Schlueter, Respondent: The Ohio State University Amy E. Hughes, www.theatrepractice.us Brooklyn College, City University of New York Website/Listserv: Travis Stern, Bradley University Playwriting Symposium Respondent: matc.us/[email protected] Lisa Langford Graduate Student Coordinators: Sean Bartley, Florida State University Shelby Lunderman, University of Washington Program Design: Tim Osborne 3 40th Mid-America Theatre Conference Symposia Co-Chairs MATC Fellows Theatre History Symposium Arthur Ballet, 1988 Shannon Walsh, Louisiana State University Jed Davis, 1988 Heidi Nees, Bowling Green State University Patricia McIlrath, 1988 Charles Shattuck, 1990 Practice/Production Symposium Ron Engle, 1993 Karin Waidley, Kenyatta University Burnet Hobgood, 1994 Wes Pearce, University of Regina Glen Q. Pierce, 1997 Julia Curtis, 1999 Playwriting Symposium Tice Miller, 2001 Eric Thibodeaux-Thompson, University of Felicia Hardison Londré, 2002 Illinois, Springfi eld Robert A. -

Horton Foote

38th Season • 373rd Production MAINSTAGE / MARCH 29 THROUGH MAY 5, 2002 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing Artistic Director Artistic Director presents the World Premiere of by HORTON FOOTE Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Composer MICHAEL DEVINE MAGGIE MORGAN TOM RUZIKA DENNIS MCCARTHY Dramaturgs Production Manager Stage Manager JENNIFER KIGER/LINDA S. BAITY TOM ABERGER *RANDALL K. LUM Directed by MARTIN BENSON Honorary Producers JEAN AND TIM WEISS, AT&T: ONSTAGE ADMINISTERED BY THEATRE COMMUNICATIONS GROUP PERFORMING ARTS NETWORK / SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P - 1 CAST OF CHARACTERS (In order of appearance) Constance ................................................................................................... *Annie LaRussa Laverne .................................................................................................... *Jennifer Parsons Mae ............................................................................................................ *Barbara Roberts Frankie ...................................................................................................... *Juliana Donald Fred ............................................................................................................... *Joel Anderson Georgia Dale ............................................................................................ *Linda Gehringer S.P. ............................................................................................................... *Hal Landon Jr. Mrs. Willis ....................................................................................................... -

Archbishop to Consecrate New Altar

wE'RE DREAMING OF A NAVY BLUE WE'RE DREAMING CHRISTMAS OF A NAVY BLUE CHRISTMAS * Vol. 23 NEW YORK, N. Y., DECEMBER 18,1942 No. 9 Archbishop to Consecrate New Altar Plan Proposed for Church's Traditional Ceremony Fordham Gives $1,550 Training of Army To Jesuit Missions To Be Held Tomorrow Morning Fordham students have con- In a ceremony, rich in liturgy and tradition, His Excellency the Most Meteorologists tinued their financial support of Reverend Francis J. Spellman, Archbishop of New York, will consecrate the missions this year to the the new altar in the University Church tomorrow morning at nine o'clock. College Training Under extent of $1,550. The monthly The new altar which was the high altar at St. Patrick's Cathedral collections in the classrooms, for sixty-three years, is a gift of the Archbishop to his alma mater. Army Rewarded With supplemented by the donation <8>In order to give the altar a suitable Air Corps Commission of the Harvester Club account setting, the Inisfad Foundation made for this total. a contribution to Fordham for the The Rev. Thomas B. Cannon, Maroon Debaters Faced with a very probable lack improving and redecoration of the S.J., Director of the Jesuit mis- sanctuary. The work is to be dedi- of qualified meteorologists in the sionary fund, earlier in the year near future, the Army Air Corps re- Reach Half-Time cated as a memorial to Mrs. William sought the aid of the Fordham Babington Macaulay, late Papal cently announced the institution of sodalists. His appeal was cen- Duchess who endowed the Inisfad a new plan enabling high school tered about the tragic effects of graduates and college students to be- With Five Wins Foundation. -

Stanley Chase Papers LSC.1090

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6h4nc876 No online items Finding Aid for the Stanley Chase Papers LSC.1090 Processed by Timothy Holland and Joshua Amberg in the Center For Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Laurel McPhee, Fall 2005; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé and edited by Josh Fiala, Caroline Cubé, Laurel McPhee and Amy Shung-Gee Wong. UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated on 2020 December 11. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Stanley Chase LSC.1090 1 Papers LSC.1090 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Stanley Chase papers Creator: Chase, Stanley Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1090 Physical Description: 157.2 Linear Feet(105 boxes, 12 oversize boxes, 27 map folders) Date (inclusive): circa 1925-2001 Date (bulk): 1955-1989 Abstract: Stanley Chase (1928-) was a theater, film, and television producer. The collection consists of production and business files, original production drawings, posters, press clippings, sound recordings, and scripts from his major projects. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements CONTAINS AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS: This collection contains both processed and unprocessed audiovisual materials. -

March 2-31 at the Waterfront Theatre on Granville Island Based on the Elephant & Piggie Books by Mo Willems

Tom Pickett (Gerald) and Kelli Ogmundson (Piggie). Photo by Tim Matheson Tim by Photo Ogmundson (Piggie). and Kelli (Gerald) Pickett Tom March 2-31 at the Waterfront Theatre on Granville Island Based on the Elephant & Piggie books by Mo Willems Published by Hyperion Books for Children Script and Lyrics by Mo Willems Music by Deborah Wicks La Puma carouseltheatre.ca|604 685 6217 carouseltheatre.ca Our Mission, Vision and Values Carousel Theatre for Young People (CTYP) creates playful, exceptional and accessible theatrical experiences that inspire, involve and educate. We envision a community that empowers people to be more imaginative, expressive and engaged. At our core, our values are playfulness, excellence, accessibility, integrity and financial accountability. Our Story Carousel Theatre for Young People (CTYP) has been creating theatre for young people since 1976. Located on Granville Island in the heart of Vancouver, CTYP is Vancouver’s professional mainstage TYA Company. We are a gathering place for artists, young people and families to embark on a journey where imagination, a dash of magic, and an abundance of play are the recipe for a theatrical adventure that has lasting impact. Our vision: to empower young people through the magic of theatre. Under the vision of Artistic Director Carole Higgins, CTYP stages vibrant stories that engage young people from the beginning of their development and continues to share stories that challenge young people through their formative years, empowering young people to become agents of positive change. Carole’s vision Stages of Play encompasses a full season that celebrates stories that explore rites of passage through our Family Stage at the Waterfront Theatre, explores Shakespeare’s canon through a contemporary lens every summer with our Teen Shakespeare Stage, and explores original Canadian creations for our BEE Stage. -

To Play the Forrest Theatre for One Week Only As Part of Kimmel Center’S Broadway Philadelphia Season! Tuesday, February 13 - Sunday, February 18, 2018

Tweet it! Sugar… butter… flour… @WaitressMusical comes to the @KimmelCenter – 2/13-2/18! Visit kimmelcenter.org for more info. #WaitressMusical #BWYPHL Press Contacts: Monica Robinson Lisa Jefferson 215-790-5847 267-765-3723 [email protected] [email protected] TO PLAY THE FORREST THEATRE FOR ONE WEEK ONLY AS PART OF KIMMEL CENTER’S BROADWAY PHILADELPHIA SEASON! TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 13 - SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 18, 2018 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, December 18, 2017) –– The Kimmel Center and The Shubert Organization are thrilled to announce Waitress will play the Forrest Theatre for a limited one-week engagement from Tuesday, February 13 through Sunday, February 18, 2018. Brought to life by a groundbreaking all-female creative team, this irresistible new hit features original music and lyrics by 6-time Grammy® nominee Sara Bareilles ("Brave," "Love Song"), a book by acclaimed screenwriter Jessie Nelson (I Am Sam), choreography by Lorin Latarro (Les Dangereuse Liasons, Waiting For Godot) and direction by Tony Award® winner Diane Paulus (Hair, Pippin, Finding Neverland). “What an honor to have this incredibly heartwarming show make its Philadelphia debut as part of our 2017-18 Broadway Philadelphia season,” said Anne Ewers, President and CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “Brought to Broadway by a group of imaginative, strong women, this film-turned- musical tells the story of another strong woman forging her own path, something to which we all can relate.” Inspired by Adrienne Shelly's beloved film, Waitress tells the story of Jenna - a waitress and expert pie maker. Jenna dreams of a way out of her small town and loveless marriage. -

Albuquerque Morning Journal, 11-26-1922 Journal Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 11-26-1922 Albuquerque Morning Journal, 11-26-1922 Journal Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_mj_news Recommended Citation Journal Publishing Company. "Albuquerque Morning Journal, 11-26-1922." (1922). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ abq_mj_news/761 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TP-T- A P TTA TTTCTTDeTh Trnrn ATS TVnn&TiP f at hjt JOURNAL iohia -- i mill) it; a it. New FACES TODAY IN VOL. CLXXV. No. 57. Albuquerque, Mexico, Sunday, November 26, 1922 24 TWO SUCTIONS PH1CK FIVE CUNTS, -j- n1 osE T'T" ('f! PEflSOWS I 30 MINERS ALSO INJURED 77.GQ0 SOIOiV iV WASHINGTON; TS TSI1EZING OUT ADMINISTRATION SUCCEEDS FIRST WOMAN SENATOR G l V A FIGHT INST THE PROFITEERS SHIPPING BILL' IN GAS BLAST AT MADRID, 10 TO 3 DEFEAT RATIFICATION OF PLAN OF SOUS; CAUSES HEATER 1 Y CAUSE IS 101 DETERMINED Harvard's Initiative and Re- ITER COMPACT Measures to Relieve the Fi- ISE WRANGLE source Overcome the nancial Plight of Farmers Big Blue Team; Clemen-cea- u Is Discussed With Hard- First of a Series of Public Big Guns on Both Sides Are Cots, Supplies, Nurses and Physi- Witnesses Contest ing at White House Surgical Meetings to Urge Its De- Turned Loose; Absent Nov. -

School Profile 2017

SCHOOL PROFILE 2017 Founded in 1981, Holy Trinity School (HTS) is Our partnerships with other organizations and a co-educational, JK-Grade 12, independent educational institutions provide a flexible day school that provides a safe, structured, and and personalized program that meets the supportive environment for students to develop needs of our students. Our Apple 1:1 Program character and values such as respect, integrity, creates a dynamic learning environment that leadership, and confidence. engages our community and fosters a creative, global, and connected classroom experience. We are leaders in learning. Our mission is rooted Technology has also enabled us to provide in academic excellence and our commitment to multiple pathways to fulfill the diverse needs our students continues to inspire us to pursue of our students. innovative teaching practices and programs to support the development of all our learners. Head of School Director of Admissions HTS.ON.CA Our program develops individual’s passions, Helen Pereira-Raso Richard Vissers skills, and knowledge that will enable them [email protected] [email protected] to thrive. This is complemented by extensive sports, music, drama, art and co-curricular Deputy Head Director of Student Success programs that provide a rich and well-rounded Peter Hill and University Placement school experience for students of every age. [email protected] Tracy Howard Mident #: 881481 At HTS, every student matters! [email protected] CEEB Code: 826583 POST SECONDARY DESTINATIONS FOR HTS GRADUATES *DESTINATIONS -

CYMBELINE" in the Fllii^Slhi TI CENTURY

"CYMBELINE" IN THE fllii^SLHi TI CENTURY Bennett Jackson Submitted in partial fulfilment for the de ree of uaster of Arts in the University of Birmingham. October 1971. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis consists of an Introduction, followed by Part I (chapters 1-2) in which nineteenth- century criticism of the play is discussed, particular attention being paid to Helen Faucit's essay on Imogen, and its relationship to her playing of the role. In Part II the stags-history of Oymbcline in London is traced from 1785 to Irving's Lyceum production of 1896. Directions from promptbooks used by G-.P. Cooke, W.C. Macready, Helen Eaucit, and Samuel ±helps are transcribed and discussed, and in the last chapter the influence of Bernard Shaw on Ellen Terry's Imogen is considered in the light of their correspondence and the actress's rehearsal copies of the play. There are three appendices: a list of performances; transcriptions of two newspaper reviews (from 1843 and 1864) and one private diary (Gordon Crosse's notes on the Lyceum Gymbeline); and discussion of one of the promptbooks prepared for Charles Kean's projected production. -

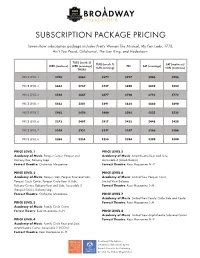

Subscription Package Pricing

2020 2021 SUBSCRIPTION PACKAGE PRICING Seven-show subscription package includes Pretty Woman The Musical, My Fair Lady, 1776, Ain’t Too Proud, Oklahoma!, The Lion King, and Hadestown. TUES (week 2) TUES (week 1) SAT (matinees) WED (matinee) WED (evenings) FRI SAT (evenings) SUN (evening) SUN (matinees) THURS PRICE LEVEL 1 $745 $862 $872 $927 $946 $956 PRICE LEVEL 2 $664 $737 $747 $800 $832 $852 PRICE LEVEL 3 $594 $667 $677 $720 $752 $772 PRICE LEVEL 4 $523 $581 $591 $634 $660 $690 PRICE LEVEL 5 $402 $450 $460 $503 $525 $535 PRICE LEVEL 6 $373 $407 $417 $433 $448 $458 PRICE LEVEL 7 $348 $331 $341 $357 $366 $366 PRICE LEVEL 8 $268 $258 $258 $284 $290 $300 PRICE LEVEL 1 PRICE LEVEL 5 Academy of Music: Parquet Center, Parquet and Academy of Music: Amphitheatre Rear and Side; Balcony Box, Balcony Loge Accessible 4 (Amphitheatre) Forrest Theatre: Orchestra, Mezzanine Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine N–P PRICE LEVEL 2 PRICE LEVEL 6 Academy of Music: Parquet Side, Parquet Rear and Side, Academy of Music: Limited View Parquet Circle, Parquet Circle Center, Parquet Circle Rear & Side, Limited View Balcony Balcony Center, Balcony Rear and Side, Accessible 2 Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine J–M (Parquet Circle), Balcony Loge Forrest Theatre: Orchestra, Mezzanine PRICE LEVEL 7 Academy of Music: Limited View Family Circle Side and Center PRICE LEVEL 3 Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine J–M Academy of Music: Family Circle Center Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine A–H PRICE LEVEL 8 Academy of Music: Limited View Amphitheatre Side and Center PRICE LEVEL 4 Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine N–P Academy of Music: Family Circle Rear and Side; Amphitheatre Center, Accessible 3 (FCCIR) Forrest Theatre: Rear Mezzanine A–H Broadway Philadelphia is presented collaboratively by the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts and The Shubert Organization 2020 2021 ADD-ON PRICING Prices listed below are inclusive of ticketing fees, excluding the $4 per order fee. -

Albuquerque Morning Journal, 07-14-1922 Journal Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 7-14-1922 Albuquerque Morning Journal, 07-14-1922 Journal Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_mj_news Recommended Citation Journal Publishing Company. "Albuquerque Morning Journal, 07-14-1922." (1922). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ abq_mj_news/626 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CITY EDITION UQUE5RQUEMORNING .. ..... mu l'ORI-- .THIRD YEAH. u mhw i n VOL. CLXX1V. No. 14. Albuquerque, New Mexico, FridayJuly 14, 1922. journal:wan j uj carrier or Man. 85c a Monlh EgSingle Copies 5o - WILL GO i FIREMEN AND SHOPMEN NOT Republican Rebels Are Defeated SCHEDULES 0 OILERS WALK BACK TILL JUSTICE IS By Irish Free State Field Guns CLOTH CAUSE ft OUT AT 7 A. II SA YS REAL SECURED, JEWELL Strike of Power Plant Em- SPLIT ployes Is Result of Dis- of Fellow Worker $ j charge G. 0. P.'S LINE UNION OFFICER LATE DEVELOPMENTS U.S. TROOPS TO for "Agitating." S IN SHOPMEN'S STRIKE S iieiween rirteen ana em- 51. twenty Ten Committee t B, Jewell, directing the of the house of the Amendments RAILWAYS shopmen's strike, said his men PROTECT LINES ployes power SH5 would not be sent back to Santa Fe shops will walk out this Are Voted Down With Aid t work and the strike would morning at 7 o'clock, and Willi of Votes From the Re- $ not he called off until "jus-tlc- e strike in sympathy with the strik-- ! has been secured." ing shop craftsmen, according to a! publican Side.