Performing Shakespeare in the Age of Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recollections and Reflections, a Professional Autobiography

... • . .... (fcl fa Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO from the estate of MARION WALKER RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS. RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS OF J. E. PLANCHE, (somerset herald). ^ |]rofcssiona( gaifobbcjrapbtr. " I ran it through, even from my boyish days, To the very moment that he bade me tell it." Othello, Act i., Scene 3. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. II. LONDON: TINSLEY BROTHERS, 18, CATHERINE STREET, STRAND. 1872. ..4^ rights reserved. LONDON BRADBURV, EVANS, AND CO., PRINTERS, WHITBFRIAR,-!. ——— CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. VAGK Another Mission to Paris—Production of " Le Domino Noir"— Mr. and Mrs. Charles Gore—Dinner at Lord Lyndhurst's Mons. Allou, Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries of France—The Duke D'Istrie and his Collection of Armour Her Majesty's Coronation—" Royal Records "—Extension of Licence to the Olympic and Adelphi Theatres—" The Drama's Levee"—Trip to Calais with Madame Yestris and Charles Mathews previous to their departure for America—Visit to Tournehem—Sketching Excursion with Charles Mathews Marriage of Madame Vestris and Charles Mathews—They sail for New York—The Olympic Theatre opened under my Direc- tion—Farren and Mrs. Nisbett engaged—Unexpected return of Mr. and Mrs. Mathews—Re-appearance of the latter in " Blue Beard "— " Faint Heart never won Fair Lady "—"The Garrick Fever"—Charles Mathews takes Covent Garden Theatre CHAPTER II. Death of Haynes Bayly—Benefit at Drury Lane for his Widow and Family—Letters respecting it from Theodore Hook and Mrs. Charles Gore—Fortunate Results of the Benefit—Tho Honourable Edmund Byng—Annual Dinner established by him in aid of Thomas Dibdin—Mr. -

Barretto: (--- ) Supported by (--- ) :0 Andmr

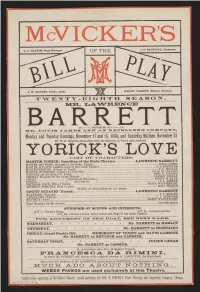

McVICKER'S L. L. SHARPE, Stage Manager. BILL OF THEPLAY C. S. REDFIELD, Treasurer. J. H. ROGERS, Scenic Artist. HENRY DOEHNE, Musical Director. T WENTY-EIGHTH SEASON. MR. LAWRENCE BARRETTO: (--- ) SUPPORTED BY (--- ) :0 ANDMR. LOUISJAMES AN EXCELLENT COMPAN Y. Monday and TuesdayEvenings, November 17 and 18, 1884, and Saturday Matinee, November 22 Mr. W. D. Howell's adaptationfrom the Spanish,in ThreeActs, entitled YORICK'S LOVE CAST OF CHARACTERS: MASTER YORICK, Comedian of the Globe Theatre LAWRENCE BARRETT MASTER HEYWOOD, Manager of the Globe Theatre LOUIS JAMES MASTER WALTON, LeadingActor of the GlobeTheatre S. E. SPRINGER MASTEREDMUND, Protege of Yorick F. C. MOSLEY MASTER WOODFORD, Authorof a NewPlay CHAS M. COLLINS GREGORY, an old servantof YorickBEN G.ROGERS THOMAS, Prompter of the Globe Theatre ALBERT RIDDLE PHILIP } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { PERCY WINTER TOBIAS } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { J. L. FINNEY MISTRESS ALICE, Wife of Yorick } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { MARIE WAINRIGHT MISTRESS DOROTHY, Maid to Alice } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { ROSA FRANCE CHANGE OF CHARACTERS IN ACT THIRD. COUNT OCTAVIO (Yorick) LAWRENCE BARRETT MANFREDO (Edmund) F. C. MOSLEY LANDOLPHO (Walton) S. E. SPRINGER BEATRICE (Alice) MARIE WAINWRIGHT Stage Manager for Mr. Barrett OLIVER DOUD SYNOPSIS OF SCENES AND INCIDENTS: ACT I.-Yorick's Home. ACT II.-Yorick's Garden. ACTIII.—Scenes 1 and 2—Green Room and Stage of old GlobeTheatre. FOR ARGUMENT OF THE PLAY, SEE NEXT PAGE. WEDNESDAY, Mr. BARRETT as HAMLET THURSDAY, Mr. BARRETT as RICHELIEU FRIDAY, Grand Double Bill, MERCHANTOF VENICE and DAVID GARRICK Mr. BARRETT- as SHYLOCK and GARRICK. SATURDAYNIGHT, JULIUS CAESAR Mr. -

In Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: the Image

Burlesquing “Otherness” 101 Burlesquing “Otherness” in Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: The Image of the Indian in John Brougham’s Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs (1847) and Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage (1855). Zoe Detsi-Diamanti When John Brougham’s Indian burlesque, Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs, opened in Boston at Brougham’s Adelphi Theatre on November 29, 1847, it won the lasting reputation of an exceptional satiric force in the American theatre for its author, while, at the same time, signaled the end of the serious Indian dramas that were so popular during the 1820s and 1830s. Eight years later, in 1855, Brougham made a most spectacular comeback with another Indian burlesque, Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage, an “Original, Aboriginal, Erratic, Operatic, Semi-Civilized, and Demi-savage Extravaganza,” which was produced at Wallack’s Lyceum Theatre in New York City.1 Both plays have been invariably cited as successful parodies of Augustus Stone’s Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags (1829) and the stilted acting style of Edwin Forrest, and the Pocahontas plays of the first half of the nineteenth century. They are sig- nificant because they opened up new possibilities for the development of satiric comedy in America2 and substantially contributed to the transformation of the stage picture of the Indian from the romantic pattern of Arcadian innocence to a view far more satirical, even ridiculous. 0026-3079/2007/4803-101$2.50/0 American Studies, 48:3 (Fall 2007): 101-123 101 102 Zoe Detsi-Diamanti -

The Tragedy of King Richard the Third. Edited by A. Hamilton Thompson

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/3edtragedyofking00shakuoft OFC 1 5 iqo? THE ARDEN SHAKESPEARE W. GENERAL EDITOR: J. CRAIG 1899-1906: R. H. CASE, 1909 THE TRAGEDY OF KING RICHARD THE THIRD *^ ^*^ THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF KING RICHARD THE THIRD EDITED BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON . ? ^^ METHUEN AND CO. LTD. 86 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON Thircf Edition First Published . August 22nd igoy Second Edition . August ^9^7 Third Edition . igi8 CONTENTS PAGB Introduction vii The Tragedy of King Richard the Third ... 7 Appendix I. 211 Appendix II 213 Appendix III. ......... 215 Appendix IV 220 " INTRODUCTION Six quarto editions of The Life and Death of Richard III. were published before the appearance of the folio of 1623. The title of the first quarto is : TRAGEDY OF King Richard THE | the third. Containing, His treacherous Plots against his | | brother Clarence: the pittiefull murther of his innocent | nephewes : his tyrannicall vsurpation : with the whole course | | of his detested life, and most deserued death. As it hath beene | lately the Right honourable the Chamber- Acted by | Lord | laine his seruants. [Prijnted by Valentine Sims, | At LONDON | for Wise, dwelling in Paules Chuch-yard \sic\ at Andrew | Signe of the Angell. the | 1597. I In the title of the second quarto (i 598), printed for Wise by Thomas Creede, the words " By William Shake-speare " occupy a new line after " seruants." The fourth, fifth, and sixth quartos also spell the author's name with a hyphen. The third quarto (1602), also printed by Creede, gives it as "Shakespeare," and adds, in a line above, the words " Newly augmented followed by a comma, which appear in the titles of the re- maining quartos. -

A Moor Propre: Charles Albert Fechter's Othello

A MOOR PROPRE: CHARLES ALBERT FECHTER'S OTHELLO A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Scott Phillips, B.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University •· 1992 Thesis Committee: Approved by Alan Woods Joy Reilly Adviser Department of Theatre swift, light-footed, and strange, with his own dark face in a rage,/ Scorning the time-honoured rules Of the actor's conventional schools,/ Tenderly, thoughtfully, earnestly, FECHTER comes on to the stage. (From "The Three Othellos," Fun 9 Nov. 1861: 76.} Copyright by Matthew Scott Phillips ©1992 J • To My Wife Margaret Freehling Phillips ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I express heartfelt appreciation to the members of my thesis committee: to my adviser, Dr. Alan Woods, whose guidance and insight made possible the completion of this thesis, and Dr. Joy Reilly, for whose unflagging encouragement I will be eternally grateful. I would also like to acknowledge the invaluable services of the British Library, the Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee Theatre Research Institute and its curator, Nena Couch. The support and encouragement given me by my family has been outstanding. I thank my father for raising my spirits when I needed it and my mother, whose selflessness has made the fulfillment of so many of my goals possible, for putting up with me. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Maggie, for her courage, sacrifice and unwavering faith in me. Without her I would not have come this far, and without her I could go no further. -

15/7/39 Liberal Arts and Sciences Department of English Charles H

The materials listed in this document are available for research at the University of Record Series Number Illinois Archives. For more information, email [email protected] or search http://www.library.illinois.edu/archives/archon for the record series number. 15/7/39 Liberal Arts and Sciences Department of English Charles H. Shattuck Papers, 1929, 1937-92 CONTENTS Box Correspondence, A-Z, 1944-61 1 Correspondence, A-Z, 1961-92 2-6 Subject File, A-W, 1929, 1946-91 6-10 Accent File, A-W, 1942-79 10 Shattuck Promptbooks, 1942-77 10-14 Playbills, 1913-88 14-15 Publications & Reviews, 1938-86 15-16 Research Notes & Correspondence, 1937-92 Macready & Booth 16-17 Shakespeare Promptbooks 17-21 Shakespeare on the American Stage 21-22 Theatre and Brecht 23 Posters & Slides 24 Box 1: Correspondence, 1944-61 A, 1946-58 Adams, John C. 1945-58, 1960 B, 1947-60 Brecht, Bertolt, 1955 C, 1947-60 D, 1946-59 E, 1946-60 Engle, Paul, 1946-56 F, 1945-60 Ford Foundation, W. McNeil Lowry, 1958-59 G, 1945-60 Gregor, Arthur, 1951-54 H, 1943-60 Harrison, G.B., 1957-58 Hewitt, Barnard, 1947-56 Hanson, Philip, 1951-57 I-K, 1942, 1947-61 L, 1946-60 M, 1944-61 15/7/39 2 N-O, 1949-60 P, 1949-60 Q, 1958-60 R, 1944-64 Sa-Sh, 1948-61 Sl-Sy, 1943-60 Stoddard, Margaret, 1954-55 Swanson, John Wesley, 1946-59 T, 1946-60 U-V, 1948-61 Vassar College, 1948-49 W, 1946-60 Wallace, Karl, 1947-49 X-Z, 1953-59 Box 2: Correspondence, 1961-92 A, 1961-92 Abou-Saif, Laila, 1964-69, 1978 Adams, John C., 1961-85 Andrews, John F., 1976-91 Andrews, Kenneth R., 1963-91 Archer, Stephen, -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zaab Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 46106 I I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. Thefollowing explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page ($)''. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. Whan an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that die photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You w ill find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections w ith a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas. Lise Brandt Pedersen Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pedersen, Lise Brandt, "Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2159. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2159 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I 72- 17,797 PEDERSEN, Lise Brandt, 1926- SHAVIAN .SHAKESPEARE:' SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, XEROXA Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan tT,TITn ^TnoT.r.a.A'TTAItf U4C PPPM MT PROPTT.MF'n FVAOTT.V AR RECEI VE D SHAVIAN SHAKESPEARE: SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Lise Brandt Pedersen B.A., Tulane University, 1952 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1963 December, 1971 ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to thank Dr. -

Ennis Cathedral

Ennis Cathedral: The Building & Its People. Saturday 29th. August 2009 Presented by the Clare Roots Society Clare Roots Society The Clare Roots Society, brainchild of Ennisman Larry Brennan, was formed in April 2006 as an amateur family history group. The Society meets once a month in Ennis, and has approx. 50 members. Anyone with an interest in tracing their family tree is welcome to join. Some members are experienced genealogists while others are novices in the field. In addition to local members, we have some 'virtual' members who live overseas, but who follow our activities via email, and dream that they are in Clare. Activities are advertised in local press and in the Ennis Cathedral church bulletin. Under the Chairmanship of Declan Barron and his committee of Fiona de Buitleir, Eric Shaw, Larry Brennan & Paddy Waldron, guest speakers were arranged at past meetings including Paul O’Donnell of the South Galway genealogy group, Peter Beirne of 'The Manse' Local Studies library in Ennis, Jim Herlihy on the RIC, Liam Curran on Irish Soldiers in the British Army, Jonny Dillon of the Folklore Dept., UCD, and Dr. Pat Nugent of the University of Liverpool amongst others. From our own members, speakers have included Dr. Paddy Waldron, Gerry Kennedy, Ger Madden, Declan Barron, Eric Shaw, Robert Cullen, and Larry Brennan. In addition, we have run a number of hands-on computer workshops on genealogical research and the recording of data. The society works in partnership with Clare County Library in order to add to the wonderful fund of genealogy information already available on their website www.clarelibrary.ie Our biggest project to date, completed in 2008 with the assistance of a grant from the Heritage Council of Ireland, involved transcription of the gravestones in the old Drumcliffe Cemetery. -

Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama James Armstrong The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2317 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] FIT FOR THE STAGE: REGENCY ACTORS AND THE INSPIRATION BEHIND ROMANTIC DRAMA by JAMES ARMSTRONG A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 ii © 2017 JAMES ARMSTRONG All Rights Reserved iii Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama by James Armstrong This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. May 12, 2017 ______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Marvin Carlson Distinguished Professor May 12, 2017 ______________________________ Date Executive Officer Peter Eckersall Professor ______________________________ Jean Graham-Jones Professor ______________________________ Annette J. Saddik Professor Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama by James Armstrong Adviser: Distinguished Professor Marvin Carlson In this dissertation, I argue that British verse tragedies of the Romantic era must be looked at not as "closet dramas" divorced from the stage, but as performance texts written with specific actors in mind. -

First Steps on the American Soil and Stage Portrait of Helena Modrzejewska by Tadeuszajdukiewicz.1880 National Museum in Krakow

January - February 2018 A Monthly Publication of the U.S. Consulate Krakow Volume XIV. Issue 152 First Steps on the American Soil and Stage Portrait of Helena Modrzejewska by TadeuszAjdukiewicz.1880 National Museum in Krakow In this issue: Helena & Raplh Modjeski Zoom in on America From Modrzejewska to Modjeska Helena Modrzejewska’s first name is present in a num- the “g” into a “j”. He spelled aloud “Modjeska.” “Now,” he ber of different languages, or has related versions such said, “it is quite easy to read, and sounds pretty, I think.” as Elena or Lena, her surname “Modrzejewska”, however, We parted good friends, and I began to make prepara- poses a real challenge to pronounce for any non-native tions for the performance of “Adrienne Lecouvreur.” speaker of the Polish language. It is no wonder then that when Modrzejewska, an already accomplished actress in Modjeska had come to America the previous year (1876) Poland, wanted to pursue her acting career in America, her with her second husband, Count Karol Bozenta Chlapow- name became a concern. It was actor John McCullough ski, and her son, Ralph, from her first marriage, and a few of the California Theater who suggested simplifying it. In friends, including writer Henryk Sienkiewicz (who later won her Memoirs and Impressions, the actress describes the the Noble Prize in Literature in 1905.) This was a politically moment when she changed her name Modrzejewska to driven immigration as the Chlapowskis’ patriotic stand put Modjeska: them in trouble with the authorities in the Russian Partition. After the rehearsal Mr. John McCullough came to speak While their ship neared the American shore, the actress to me. -

“Revenge in Shakespeare's Plays”

“REVENGE IN SHAKESPEARE’S PLAYS” “OTHELLO” – LECTURE/CLASS WRITTEN: 1603-1604…. although some critics place the date somewhat earlier in 1601- 1602 mainly on the basis of some “echoes” of the play in the 1603 “bad” quarto of “Hamlet”. AGE: 39-40 Years Old (B.1564-D.1616) CHRONO: Four years after “Hamlet”; first in the consecutive series of tragedies followed by “King Lear”, “Macbeth” then “Antony and Cleopatra”. GENRE: “The Great Tragedies” SOURCES: An Italian tale in the collection “Gli Hecatommithi” (1565) of Giovanni Battista Giraldi (writing under the name Cinthio) from which Shakespeare also drew for the plot of “Measure for Measure”. John Pory’s 1600 translation of John Leo’s “A Geographical History of Africa”; Philemon Holland’s 1601 translation of Pliny’s “History of the World”; and Lewis Lewkenor’s 1599 “The Commonwealth and Government of Venice” mainly translated from a Latin text by Cardinal Contarini. STRUCTURE: “More a domestic tragedy than ‘Hamlet’, ‘Lear’ or ‘Macbeth’ concentrating on the destruction of Othello’s marriage and his murder of his wife rather than on affairs of state and the deaths of kings”. SUCCESS: The tragedy met with high success both at its initial Globe staging and well beyond mainly because of its exotic setting (Venice then Cypress), the “foregrounding of issues of race, gender and sexuality”, and the powerhouse performance of Richard Burbage, the most famous actor in Shakespeare’s company. HIGHLIGHT: Performed at the Banqueting House at Whitehall before King James I on 1 November 1604. AFTER: The play has been performed steadily since 1604; for a production in 1660 the actress Margaret Hughes as Desdemona “could have been the first professional actress on the English stage”.