Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT WHAT IF YOU're LONELY: JESSICA STORIES By

ABSTRACT WHAT IF YOU’RE LONELY: JESSICA STORIES by Michael Stoneberg This novel-in-stories follows Jessica through the difficulties of her early twenties to her mid- thirties. During this period of her life she struggles with loneliness and depression, attempting to find some form of meaningful connection through digital technologies as much as face-to-face interaction, coming to grips with a non-normative sexuality, finding and losing her first love and dealing with the resultant constant pull of this person on her psyche, and finally trying to find who in fact she, Jessica, really is, what version of herself is at her core. The picture of her early adulthood is drawn impressionistically, through various modes and styles of narration and points of view, as well as through found texts, focusing on preludes and aftermaths and asking the reader to intuit and imagine the spaces between. WHAT IF YOU’RE LONELY: JESSICA STORIES A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Michael Stoneberg Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2014 Advisor______________________ Margaret Luongo Reader_______________________ Joseph Bates Reader_______________________ Madelyn Detloff TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Revision Page 1 2. Invoice for Therapy Services Page 11 3. Craigslist Page 12 4. Some Things that Make Us—Us Page 21 5. RE: Recent Account Activity Page 30 6. Sirens Page 31 7. Hand-Gun Page 44 8. Hugh Speaks Page 48 9. “The Depressed Person” Page 52 10. Happy Hour: Last Day/First Day Page 58 11. -

MISALLIANCE : Know-The-Show Guide

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey MISALLIANCE: Know-the-Show Guide Misalliance by George Bernard Shaw Know-the-Show Audience Guide researched and written by the Education Department of The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey Artwork: Scott McKowen The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey MISALLIANCE: Know-the-Show Guide In This Guide – MISALLIANCE: From the Director ............................................................................................. 2 – About George Bernard Shaw ..................................................................................................... 3 – MISALLIANCE: A Short Synopsis ............................................................................................... 4 – What is a Shavian Play? ............................................................................................................ 5 – Who’s Who in MISALLIANCE? .................................................................................................. 6 – Shaw on — .............................................................................................................................. 7 – Commentary and Criticism ....................................................................................................... 8 – In This Production .................................................................................................................... 9 – Explore Online ...................................................................................................................... 10 – Shaw: Selected -

3. Terence Rattigan- First Success and After

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „In and out of the limelight- Terence Rattigan revisited“ Verfasserin Covi Corinna angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 30. Jänner 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: 343 Diplomstudium Anglistik und Amerikanistik UniStG Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Rudolf Weiss Table of contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………....p.4 2. The History of the Well-Made Play…………………………......p.5 A) French Precursors.....................................................................p.6 B) The British Well-Made Play...................................................p.10 a) Tom Robertson and the 1870s...........................................................p.10 b) The “Renaissance of British Drama”...............................................p.11 i. Arthur Wing Pinero (1855-1934) and Henry Arthur Jones (1851- 1929)- The precursors of the “New Drama”..............................p.12 ii. Oscar Wilde (1854-1900)..............................................................p.15 c) 1900- 1930 “The Triumph of the New Drama”...............................p.17 i. Harley Granville-Barker (1877-1946)………………................p.18 ii. William Somerset Maugham (1874-1965)..................................p.18 iii. Noel Coward (1899-1973)............................................................p.20 3. Terence Rattigan- first success and after...................................p.21 A) French Without Tears (1936)...................................................p.22 -

Sources of Lear

Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Lynne Bradley, 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) Abstract The temptation to meddle with Shakespeare has proven irresistible to playwrights since the Restoration and has inspired some of the most reviled and most respected works of theatre. Nahum Tate’s tragic-comic King Lear (1681) was described as an execrable piece of dementation, but played on London stages for one hundred and fifty years. David Garrick was equally tempted to adapt King Lear in the eighteenth century, as were the burlesque playwrights of the nineteenth. In the twentieth century, the meddling continued with works like King Lear’s Wife (1913) by Gordon Bottomley and Dead Letters (1910) by Maurice Baring. -

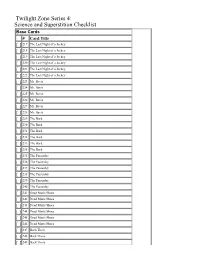

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff | the American Conservative

10/26/2017 Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff | The American Conservative BLOGS POLITICS WORLD CULTURE EVENTS NEW URBANISM ABOUT DONATE The Right’s Redeeming the Happy Birthday, I Fought a War How Saddam Ezra Pound, Shutting Up The Strangene Biggest Wedge Debauched Hillary Against Iran— Hussein Locked Away Richard Spencer of ‘Stranger Issue: Donald Falstaff and It Ended Predicted Things’ Trump Badly America’s Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff Do not moralize---there is a little of Shakespeare's 'Fat Knight' in all of us. By ALLEN MENDENHALL • October 26, 2017 Like 3 Share Tweet Falstaff und sein Page, by Adolf Schrödter, 1866 (Public Domain). Falstaff: Give Me Life (Shakespeare’s Personalities) Harold Bloom, Scribner, 176 pages. In The Daemon Knows, published in 2015, the heroic, boundless Harold Bloom claimed to have one more book left in him. If his contract with Simon & Schuster is any indication, he has more work than that to complete. The effusive 86-year-old has agreed to produce a sequence of five books on Shakespearean personalities, presumably those with whom he’s most enamored. The first, recently released, is Falstaff: Give Me Life, which has been called an “extended essay” but reads more like 21 ponderous essay-fragments, as though Bloom has compiled his notes and reflections over the years. The result is a solemn, exhilarating meditation on Sir John Falstaff, the cheerful, slovenly, degenerate knight whose unwavering and ultimately self- destructive loyalty to Henry of Monmouth, or Prince Hal, his companion in William Shakespeare’s Henry trilogy (“the Henriad”), redeems his otherwise debauched character. http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/redeeming-the-debauched-falstaff/ 1/4 10/26/2017 Redeeming the Debauched Falstaff | The American Conservative Except Bloom doesn’t see the punning, name-calling Falstaff that way. -

![ONE NIGHT @ the CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset By: Arun K Gupta]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7467/one-night-the-call-center-chetan-bhagat-typeset-by-arun-k-gupta-1187467.webp)

ONE NIGHT @ the CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset By: Arun K Gupta]

ONE NIGHT @ THE CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset by: Arun K Gupta] This is someway my story. A great fun, inspirational One! Before you begin this book, I have a small request. Right here, note down three things. Write down something that i) you fear, ii) makes you angry and iii) you don’t like about yourself. Be honest, and write something that is meaningful to you. Do not think too much about why I am asking you to do this. Just do it. One thing I fear: __________________________________ One thing that makes me angry: __________________________________ One thing I do not like about myself: __________________________________ Okay, now forget about this exercise and enjoy the story. Have you done it? If not, please do. It will enrich your experience of reading this book. If yes, thanks Sorry for doubting you. Please forget about the exercise, my doubting you and enjoy the story. PROLOGUE _____________ The night train ride from Kanpur to Delhi was the most memorable journey of my life. For one, it gave me my second book. And two, it is not every day you sit in an empty compartment and a young, pretty girl walks in. Yes, you see it in the movies, you hear about it from friend’s friend but it never happens to you. When I was younger, I used to look at the reservation chart stuck outside my train bogie to check out all the female passengers near my seat (F-17 to F-25)is what I’d look for most). Yet, it never happened. -

Heartbreak House

Heartbreak House George Bernard Shaw Heartbreak House Table of Contents Heartbreak House.....................................................................................................................................................1 George Bernard Shaw....................................................................................................................................1 HEARTBREAK HOUSE: A FANTASIA IN THE RUSSIAN MANNER ON ENGLISH THEMES........1 HEARTBREAK HOUSE AND HORSEBACK HALL................................................................................1 HEARTBREAK HOUSE..........................................................................................................................................18 ACT I...........................................................................................................................................................18 ACT II.......................................................................................................................................................................46 ACT III......................................................................................................................................................................77 i Heartbreak House George Bernard Shaw This page copyright © 2001 Blackmask Online. http://www.blackmask.com • HEARTBREAK HOUSE AND HORSEBACK HALL • HEARTBREAK HOUSE • ACT I • ACT II • ACT III This Etext was produced by Eve Sobol, South Bend, Indiana, USA HEARTBREAK HOUSE: A FANTASIA IN THE RUSSIAN MANNER -

Performing Shakespeare in the Age of Empire Richard Foulkes Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-63022-1 - Performing Shakespeare in the Age of Empire Richard Foulkes Frontmatter More information PERFORMING SHAKESPEARE IN THE AGE OF EMPIRE During the nineteenth century the performance of Shakespeare’s plays contributed significantly to the creation of a sense of British nationhood at home and the extension of her influence overseas, not only in her own empire but also in North America and Europe. This was achieved through the enterprise of the commercial theatre rather than state subsidy and institutions. Britain had no National Theatre, but Shakespeare’s plays were performed up and down the land from the fashionable West End to the suburbs of the capital and the expanding industrial conurbations to the north. British actors also travelled the world to perform Shakespeare’s plays, while foreign actors regarded success in London as the ultimate seal of ap- proval. In this book Richard Foulkes explores the political and social uses of Shakespeare through the nineteenth and into the twentieth century and the movement from the business of Shakespeare as an enterprise to that of enshrinement as a cultural icon. With the prospect of the tercentenary of Shakespeare’s death in 1916 the campaign for a Shakespeare Memorial National Theatre gathered pace. This was promoted as a benefit to the whole English- speaking world and the equal of the state theatres of Europe, but it fell victim to the outbreak of war, which coincided with a decline in traditional Shakespeare and exposed the nation’s lack of any institutional -

HEARTBREAK HOUSE by George Bernard Shaw Directed by John Going

2006—2007 SEASON HEARTBREAK HOUSE by George Bernard Shaw Directed by John Going CONTENTS 2 The 411 3 A/S/L & HTH 4 FYI 5 RBTL 6IRL 7 F2F 8 SWDYT? STUDY GUIDES ARE SUPPORTED BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM CITIGROUP MISSOURI ARTS COUNCIL MIHYAP: TOP TEN WAYS TO STAY CONNECTED AT THE REP At The Rep, we know that life moves fast— 10. TBA Ushers will seat your school or class as a group, okay, really fast. so even if you are dying to mingle with the group from the But we also know all girls school that just walked in the door, stick with your that some things friends until you have been shown your section in the are worth slowing down for. We believe that live theatre is theatre. one of those pit stops worth making and are excited that 9. SITD The house lights will dim immediately before the you are going to stop by for a show. To help you get the performance begins and then go dark. Fight off that oh-so- most bang for your buck, we have put together immature urge to whisper, giggle like a grade schooler, or WU? @ THE REP—an IM guide that will give you yell at this time and during any other blackouts in the show. everything you need to know to get at the top of your 8. SED Before the performance begins, turn off all cell theatergoing game—fast. You’ll find character descriptions phones, pagers, beepers and watch alarms. If you need to (A/S/L), a plot summary (FYI), biographical information text, talk, or dial back during intermission, please make sure on the playwright (F2F), historical context (B4U), and to click off before the show resumes. -

Fade In: Int. Art Gallery – Day

FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY Exhibition Guide FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY March 03 – May 08, 2016 Works by Danai Anesiadou, Nairy Baghramian, Michael Bell-Smith, Dora Budor, Heman Chong, Mike Cooter, Brice Dellsperger, GALA Committee, Mathis Gasser, Jamian Juliano-Villani, Bertrand Lavier, William Leavitt, Christian Marclay, Rodrigo Matheus, Allan McCollum, Henrique Medina, Carissa Rodriguez, Cindy Sherman, Amie Siegel, Scott Stark, and Albert Whitlock; performances and public programs by Casey Jane Ellison, Mario García Torres, Alex Israel, Thirteen Black Cats, and more. Recasting the gallery as a set for dramatic scenes, FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY explores the role that art plays in narrative film and television. FADE IN features the work of 25 artists and considers a history of art as seen in classic movies, soap operas, science fiction, pornography and musicals. These works have been sourced, reproduced and created in response to artworks that have been made to appear on-screen, whether as props, set dressings, plot devices, or character cues. The nature of the exhibition is such that sculptures, paintings and installations transition from prop to image to art object, staging an enquiry into whether these fictional depictions in mass media ultimately have greater influence in defining a collective understanding of art than art itself does. Certain preoccupations with artworks are established early on in cinematic history: the preciousness of art objects anchors their roles as plot drivers, and anxieties intensify regarding the vitality of artworks and their perceived abilities to wield power over viewers or to capture spirits. Such themes were famously explored in the 1945 film adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, from which Cindy Sherman has sourced the original portrait painted for the production. -

![The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear As Inscriptive Site John Rempel](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3600/the-history-of-king-lear-1681-lear-as-inscriptive-site-john-rempel-1643600.webp)

The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear As Inscriptive Site John Rempel

Document generated on 09/29/2021 12:39 a.m. Lumen Selected Proceedings from the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies Travaux choisis de la Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site John Rempel Theatre of the world Théâtre du monde Volume 17, 1998 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1012380ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1012380ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle ISSN 1209-3696 (print) 1927-8284 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Rempel, J. (1998). Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site. Lumen, 17, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.7202/1012380ar Copyright © Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle, 1998 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 3. Nahum Tate's ('aberrant/ 'appalling') The History of King Lear [1681]: Lear as Inscriptive Site From Addison in 1711 ('as it is reformed according to the chimerical notion of poetical justice, in my humble opinion it has lost half its beauty') to Michael Dobson in 1992 (Shakespeare 'serves for Tate ..