ABSTRACT WHAT IF YOU're LONELY: JESSICA STORIES By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Words & Images 2009

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Words and Images College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences 2009 Words & Images 2009 University of Southern Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/words-and-images Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation University of Southern Maine, "Words & Images 2009" (2009). Words and Images. 9. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/words-and-images/9 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Words and Images by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. words and Images Whom you should blame: Seth A. Bishop 2009. was the Managing Editor; Chad Chamberlain was a Fiction Edi tor; Jeff Hodenberg was a Poetry Editor; Jill Jacobs was a Fiction Editor; Benjamin Rybeck was the Publishing Director; Aubin Thomas was the Art Director; Caroline O'Connor Thomas was a Poetry Editor. Words and Images is a publication of the University of Southern Maine. We welcome submissions of poetry, short fiction, and creative nonfiction. Please address correspondences to: Words and Images, University of Southern Maine, P.O. Box Portland, Maine, Copyright 9300, 04104. 2009 by Words and Images. All right reserved. No part of this pub lication may be reproduced in any form or by any means with out permission by the publisher. Words and Images was 2009 published through the generosity of the 37th Student Senate, the Student Government Association, the Student Activity Fee, and, of course, the student body, all of which are located at good old Universit of Southern Maine. -

View Mirror to the Windshield Had Melted Off in the Heat, So I Turned Around in My Seat and Watched the Gravel Driveway As I Backed Out

ABSTRACT THE DIRT ON DOREEN AND OTHER NEWS by Meagan Sliger This collection of short stories is centered on a small town dynamic in which characters that have been raised on idle gossip and provincial ideas begin to question the values they have grown up with. Set primarily in Southwestern Ohio, the belief systems these characters have been carrying are challenged in unexpected ways. The stories are arranged in the reverse chronological order from which they were written. THE DIRT ON DOREEN AND OTHER NEWS A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts Department of English By Meagan Elizabeth Sliger Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2008 Advisor: Margaret Luongo Reader: Brian Roley Reader: Tim Melley CONTENTS 1. THE RACE 1 2. THE DIRT ON DOREEN 5 3. SOME OLD GUY LIKE ME 15 4. MUZZLE 20 5. THE HUMPS 31 6. HOUSE OF HOSPITATLITY 37 7. HOW TO BOIL A HOUSEWIFE 46 8. MABEL AND GOLIATH 53 ii THE RACE I have entered a road race. It is a 5k and I believe I will win my age group if not the entire race overall. For the women, of course. I am not fast enough to contend with the men. I believe I will win, because I believe if I believe I will win then it is likely that I will. More likely anyway than if I believe I will not win. So I stand at the starting line telling myself I will win, telling myself I am faster than all the other women here and that I can, without question, win the race. -

Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas. Lise Brandt Pedersen Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pedersen, Lise Brandt, "Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2159. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2159 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I 72- 17,797 PEDERSEN, Lise Brandt, 1926- SHAVIAN .SHAKESPEARE:' SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, XEROXA Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan tT,TITn ^TnoT.r.a.A'TTAItf U4C PPPM MT PROPTT.MF'n FVAOTT.V AR RECEI VE D SHAVIAN SHAKESPEARE: SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Lise Brandt Pedersen B.A., Tulane University, 1952 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1963 December, 1971 ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to thank Dr. -

The AGA Song Book up to Date

3rd Edition Songs, Poems, Stories and More! Edited by Bob Felice Published by The American Go Association P.O. Box 397, Old Chelsea Station New York, N.Y., 10113-0397 Copyright 1998, 2002, 2006 in the U.S.A. by the American Go Association, except where noted. Cover illustration by Jim Rodgers. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission of the copyright holder, except for brief quotations used as part of a critical review. Introductions Introduction to the 1st Edition When I attended my first Go Congress three years ago I was astounded by the sheer number of silly Go songs everyone knew. At the next Congress, I wondered if all these musical treasures had ever been printed. Some research revealed that the late Bob High had put together three collections of Go songs, but the last of these appeared in 1990. Very few people had these song books, and some, like me, weren’t even aware that they existed. While new songs had been printed in the American Go Journal, there was clearly a need for a new collection of Go songs. Last year I decided to do whatever I could to bring the AGA Song Book up to date. I wanted to collect as many of the old songs as I could find, as well as the new songs that had been written since Bob High’s last song book. You are holding in your hands the book I was looking for two years ago. -

Durabteilung Beginn Auf 1, Eventuell Zweite Molltonika

Vier unterschiedliche Stufen Durabteilung Beginn auf 1, eventuell zweite Molltonika 1234 Parallelprogression Ärzte, Die: Himmelblau (S, G), Beatles, The: Here there and everywhere (S), Culcha Candela: Hamma! (S), Cure, The: Boys don't cry (S, R), Billy Joel: Uptown girl (S 123[45]), Juanes: La camisa negra (R), Mark Forster: Bauch und Kopf (R 123/74) 1235 (Parallelprogression), 1236 (Parallelprogression), 1243 1245 7 Years Bad Luck (Punkrock): A plain guide (to happiness) (I), Aerger (Deutschpop): Kleine Schwester (I, R) Vanessa Amorosi (Bravopop): Shine (R), Tina Arena (Cover): Show me heaven (R), Bachman Turner Overdrive: Hey you (R), Jennifer Brown: Naked (I, R), Joe Cocker: No ordinary world (R), Jude Cole: Madison (S, R), Corrs, The: All the love in the world (S), Counting Crows: Rain king (R), Nelly Furtado: In god’s hands (R), Faith Hill: Breathe (R), Gewohnheitstrinker (Punk): High Society (R), Michael Jackson: My girl (B), Jack Johnson: Upside down (R), Labrinth feat. Emeli Sandé (Reggae): Beneath your beautiful (T), Fady Maalouf (Bravopop): Blessed (Rf), Maroon 5 (Alternativepop): Won’t go home without you (R11224511), Amanda Marshall: Fall from Grace (I, S, R), Don McLean: Vincent (S), Melanie C: If that were me (S, R), Metro Station (Bravopop): Shake it (B), Alanis Morissette: Ur (T), Nena: 99 Luftballons (S, R), Laura Pausini: Il mio sbaglio più grande (I, S, R), Katy Perry: Thinking of you (R bzw. 124-4), Reamon: Josephine (I, S), Reel Big Fish (Skarock): Somebody hates me (Rf), Sell out (I, S, Z1), Savage Garden: I knew -

Alan Sillitoe the LONELINESS of the LONG- DISTANCE RUNNER

Alan Sillitoe THE LONELINESS OF THE LONG- DISTANCE RUNNER Published in 1960 The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner Uncle Ernest Mr. Raynor the School-teacher The Fishing-boat Picture Noah's Ark On Saturday Afternoon The Match The Disgrace of Jim Scarfedale The Decline and Fall of Frankie Buller The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner AS soon as I got to Borstal they made me a long-distance cross-country runner. I suppose they thought I was just the build for it because I was long and skinny for my age (and still am) and in any case I didn't mind it much, to tell you the truth, because running had always been made much of in our family, especially running away from the police. I've always been a good runner, quick and with a big stride as well, the only trouble being that no matter how fast I run, and I did a very fair lick even though I do say so myself, it didn't stop me getting caught by the cops after that bakery job. You might think it a bit rare, having long-distance crosscountry runners in Borstal, thinking that the first thing a long-distance cross-country runner would do when they set him loose at them fields and woods would be to run as far away from the place as he could get on a bellyful of Borstal slumgullion--but you're wrong, and I'll tell you why. The first thing is that them bastards over us aren't as daft as they most of the time look, and for another thing I'm not so daft as I would look if I tried to make a break for it on my longdistance running, because to abscond and then get caught is nothing but a mug's game, and I'm not falling for it. -

Legion of Decency Is Lauded by Pontiff

HP mm LEGION OF DECENCY IS LAUDED BY PONTIFF Yearly Report Given fh t R tfisttr H it thi InUrnitional N tv t Strvicl (Wiri and Mail), tin N. C. W. C. Newt Service (Includiaf Radios and Cables), Its Own Special Service. AH the Smaller Catholic Services, IntematloBai Illustrated News, and N. C, W. C Picture Service. SAYS CRUSADE DE PAUL MEN Local Local The Michigan Catholic, Edition Edition Detroit, tells us that *‘mem- SHOULD SPREAD bers of the Black Legion used EXPEND CLOSE to borrow chairs for their THE meetings from a Catholic un dertaker." TO ALL WORLD TO 6 MILLION 4 Father Charles E. Cough lin’s weekly, “Social Jus Encyclical Asserts ‘Painstaking Vigilance tice," just a few months old, Great Charity Work of Group Reveals Over Motion Pictures’ Is Necessary REGISTER(Name Registered in the U. S. Patent Office) has passed the million mark Fine Spiritual Achievement as To Protect Morality in circulation, with relative VOL. XII. No. 28 DENVER, COLO., SUNDAY, JULY 12,1936 TWO CENTS ly few free copies. Well as Material Aid Vatican City.— Utilizing the formal and impressive Leaders to Attend medium of an Encyclical letter. Pope Pius XI has bestowed “Washington Merry-Go- Washington.—^The annual report of the Superior coun Priest-Scientist at Field Work high praise on the crusade against immoral motion pictures Round,” a syndicated col cil, Society of St. Vincent*de Paul, shows that the amount conducted under the leadership of the American Hier of relief distributed by the organization in the year ended umn, not long ago carried an archy; has expressed a wish for its continuance; and has item about a cousin of Roose Sept. -

Quest Magazine Vol 15 Issue 17

LAWTON KICKS OFF FAIR WISCONSIN’S “GO ALL THE WAY” ELECTION RALLY UW-Madison Event Start Of Statewide Campus Campaign Madison - Wisconsin lieutenant brightest unless you happen to Judge co-founded Students for a Fair Wis - governor Barbara Lawton head - be gay, lesbian, bisexual (or) consin to build student opposition to the lined a rally for UW-students transsexual,” Lawton said. 2006 ballot measure that banned gay civil here October 15 urging atten - Fair Wisconsin’s “Go All The unions marriage as well as legal recognition dees to vote in state and local Way On Election Day” addresses for all unmarried couples regardless of sexual elections and help elect candi - the fact that the state is only orientation. dates who support LGBT rights. three seats away from having a “We as students have an undeniable legacy to LGBT rights advocacy group Fair pro-fairness majority in both fight for what is right,” Judge said. “The state Wisconsin sponsored the rally as houses of the State Legislature. Legislature is the first step. It’s the spear that we part of its “Go All the Way on A high turnout, particularly need to start reversing the effects of the ban.” Election Day” campaign to en - among younger voters who tend UW-Madison College Democrats Chair Claire courage students to vote to be more supportive of LGBT Rydell also spoke at the rally, expressing her through the entire ballot, especially at the equality will be very important. concern over students who don’t consider state level. The campaign is running on col - “The only way to change the leadership in casting their ballot to be important enough to lege campuses statewide. -

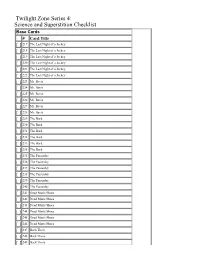

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

It's a Wonderful Life Final Script Opening Sequence/George Saves

It's a Wonderful Life Final Script Opening sequence/George saves Harry FADE IN –– NIGHT SEQUENCE Series of shots of various streets and buildings in the town of Bedford Falls, somewhere in New York State. The streets are deserted, and snow is falling. It is Christmas Eve. Over the above scenes we hear voices praying: GOWER'S VOICE I owe everything to George Bailey. Help him, dear Father. MARTINI'S VOICE Joseph, Jesus and Mary. Help my friend Mr. Bailey. MRS. BAILEY'S VOICE Help my son George tonight. BERT'S VOICE He never thinks about himself, God; that's why he's in trouble. ERNIE'S VOICE George is a good guy. Give him a break, God. MARY'S VOICE I love him, dear Lord. Watch over him tonight. JANIE'S VOICE Please, God. Something's the matter with Daddy. ZUZU'S VOICE Please bring Daddy back. CAMERA PULLS UP from the Bailey home and travels up through the sky until it is above the falling snow and moving slowly toward a firmament full of stars. As the camera stops we hear the following heavenly voices talking, and as each voice is heard, one of the stars twinkles brightly: FRANKLIN'S VOICE Hello, Joseph, trouble? JOSEPH'S VOICE Looks like we'll have to send someone down –– a lot of people are asking for help for a man named George Bailey. FRANKLIN'S VOICE George Bailey. Yes, tonight's his crucial night. You're right, we'll have to send someone down immediately. Whose turn is it? JOSEPH'S VOICE That's why I came to see you, sir. -

Lamplight FALL 2009 FRIENDS of NURSING NEWSLETTER President’S Message

1 Lamplight FALL 2009 FRIENDS OF NURSING NEWSLETTER President’s Message Dr. Mary Jo Coast, President Dear FON Members, The Friends of Nursing publishes its newsletter, the lamplight, every fall. If you s we embark upon a new season of have noteworthy information to share with events and activities, I am struck by the membership, please send an article to any A our sense of commitment and passion of the board members, and we will get it to for the mission of Friends of Nursing: To the proper person for publication. Our advance professional nursing by providing publication is intended to share important scholarships for quality education in news, ideas, and thoughts of its membership. baccalaureate and higher degree programs in Please note when the FON Board of Directors Colorado Schools of Nursing and improve the meet. If you have any questions and/or health of Colorado communities. concerns, please feel free to contact any board member or me to have your questions As president, I am honored to be working and/or concerns presented to the board. We with the Board of Directors and the will respond in a timely manner. Membership of the Friends of Nursing, Additionally, the 2000 -2010 calendar of established by a small group of women in events can be found in the membership roster 1981who wanted to improve the quality of and this issue of the Lamplight. health care through educational support of The FON Board Members and I look forward the profession of nursing and ensure that Sincerely, those who sought nursing education had financial help in doing so.