ONE NIGHT @ the CALL CENTER —CHETAN BHAGAT [Typeset By: Arun K Gupta]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stirring the Pot Ingredients for Effective Communication

Stirring the Pot Ingredients for Effective Communication An Inviting Guide to the Invigorating Art of Dialogue Interpersonal Communication Strategic Process / Event Design Facilitation and Conflict Resolution 1 Table of Contents Page 1.) Introduction 1.1 Manual/Workbook Objectives 4 1.2 Taking a “Communication Perspective” 5 2.) Strategic Process Design 2.1 Strategic Process/Design Clear Objectives 5 2.2 Analyze Use of Time 6 2.3 Develop an Agenda 6 2.4 Plan Meeting to Achieve Goals 7 2.5 Transparent Objectives and Task Orientation 7 2.6 Trust and Relationship Building 7 2.7 Encourage Ownership and “Buy In” of the Process 8 2.8 Logistical Considerations 8-9 2.9 Closing Procedures 9-10 3.) Interpersonal Communication 3.1 Active Listening 10 3.2 Paraphrasing or “Reflecting” 10-11 3.3 Non-Verbal Communication 11-12 3.4 Reflexivity and the Relationship Between Conversants 12 3.5 Dialogue or Debate? 12-13 3.6 Appreciative Inquiry 13-14 3.7 Re-framing 14 3.8 Prefigurative Language 14-15 3.9 Eliciting “Stories” 15 4.) Facilitation Skills 4.1 Ground Rules 15-16 4.2 Neutrality 16 4.3 Enriching the Conversation 16 4.4 Curiosity and Wonder 16-17 4.5 Pick up the “Power Language” 17 4.6 “Deontic” Logic 17 4.7 Third Person Positioning 17-18 4.8 Asking Systemic or “Circular” Questions 18 2 4.9 Listen for the “Voices” 18 4.10 Typical Communication Archetypes 19-22 4.11 Conflict is Positive 22 4.12 Conflict Management 23-24 4.13 Heading off Trouble 24-25 4.14 Encouraging Differences of Opinion 25-26 4.15 Drawing Connections 26 4.16 Imagine Possible Futures -

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love You 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 911 More Than A Woman 1927 Compulsory Hero 1927 If I Could 1927 That's When I Think Of You Ariana Grande Dangerous Woman "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Eat It "Weird Al" Yankovic White & Nerdy *NSYNC Bye Bye Bye *NSYNC (God Must Have Spent) A Little More Time On You *NSYNC I'll Never Stop *NSYNC It's Gonna Be Me *NSYNC No Strings Attached *NSYNC Pop *NSYNC Tearin' Up My Heart *NSYNC That's When I'll Stop Loving You *NSYNC This I Promise You *NSYNC You Drive Me Crazy *NSYNC I Want You Back *NSYNC Feat. Nelly Girlfriend £1 Fish Man One Pound Fish 101 Dalmations Cruella DeVil 10cc Donna 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc I'm Mandy 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Wall Street Shuffle 10cc Don't Turn Me Away 10cc Feel The Love 10cc Food For Thought 10cc Good Morning Judge 10cc Life Is A Minestrone 10cc One Two Five 10cc People In Love 10cc Silly Love 10cc Woman In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 2 Unlimited No Limit 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 2nd Baptist Church (Lauren James Camey) Rise Up 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

ABSTRACT WHAT IF YOU're LONELY: JESSICA STORIES By

ABSTRACT WHAT IF YOU’RE LONELY: JESSICA STORIES by Michael Stoneberg This novel-in-stories follows Jessica through the difficulties of her early twenties to her mid- thirties. During this period of her life she struggles with loneliness and depression, attempting to find some form of meaningful connection through digital technologies as much as face-to-face interaction, coming to grips with a non-normative sexuality, finding and losing her first love and dealing with the resultant constant pull of this person on her psyche, and finally trying to find who in fact she, Jessica, really is, what version of herself is at her core. The picture of her early adulthood is drawn impressionistically, through various modes and styles of narration and points of view, as well as through found texts, focusing on preludes and aftermaths and asking the reader to intuit and imagine the spaces between. WHAT IF YOU’RE LONELY: JESSICA STORIES A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Michael Stoneberg Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2014 Advisor______________________ Margaret Luongo Reader_______________________ Joseph Bates Reader_______________________ Madelyn Detloff TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Revision Page 1 2. Invoice for Therapy Services Page 11 3. Craigslist Page 12 4. Some Things that Make Us—Us Page 21 5. RE: Recent Account Activity Page 30 6. Sirens Page 31 7. Hand-Gun Page 44 8. Hugh Speaks Page 48 9. “The Depressed Person” Page 52 10. Happy Hour: Last Day/First Day Page 58 11. -

The Truth About Voter Fraud 7 Clerical Or Typographical Errors 7 Bad “Matching” 8 Jumping to Conclusions 9 Voter Mistakes 11 VI

Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A sin- gular institution—part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group—the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advocacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S VOTING RIGHTS AND ELECTIONS PROJECT The Voting Rights and Elections Project works to expand the franchise, to make it as simple as possible for every eligible American to vote, and to ensure that every vote cast is accurately recorded and counted. The Center’s staff provides top-flight legal and policy assistance on a broad range of election administration issues, including voter registration systems, voting technology, voter identification, statewide voter registration list maintenance, and provisional ballots. © 2007. This paper is covered by the Creative Commons “Attribution-No Derivs-NonCommercial” license (see http://creativecommons.org). It may be reproduced in its entirety as long as the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is credited, a link to the Center’s web page is provided, and no charge is imposed. The paper may not be reproduced in part or in altered form, or if a fee is charged, without the Center’s permission. -

Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas. Lise Brandt Pedersen Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pedersen, Lise Brandt, "Shavian Shakespeare: Shaw's Use and Transformation of Shakespearean Materials in His Dramas." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2159. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2159 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I 72- 17,797 PEDERSEN, Lise Brandt, 1926- SHAVIAN .SHAKESPEARE:' SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, XEROXA Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan tT,TITn ^TnoT.r.a.A'TTAItf U4C PPPM MT PROPTT.MF'n FVAOTT.V AR RECEI VE D SHAVIAN SHAKESPEARE: SHAW'S USE AND TRANSFORMATION OF SHAKESPEAREAN MATERIALS IN HIS DRAMAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Lise Brandt Pedersen B.A., Tulane University, 1952 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1963 December, 1971 ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to thank Dr. -

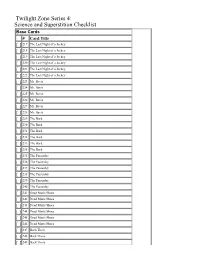

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

GAMER Written by Mark Neveldine & Brian Taylor September 2007 Some

GAMER Written by Mark Neveldine & Brian Taylor September 2007 Some of them want to use you Some of them want to get used by you Some of them want to abuse you Some of them want to be abused - Eurythmics Some years from this exact moment... 1 INT. TRAIN - DAY 1 DARKNESS - NOW The beautiful CHIMING SOUNDS OF SPACE TRAVEL through the COSMOS... DOTS OF LIGHT whiz past our face. They could be stars at lightspeed, or... SUBWAY LIGHTS FLICKER ON - in a flash we see PALE, SULLEN FACES, riding into a bleak future, and hear the INDUSTRIAL CLATTER. It's dark, claustrophobic, obscure... the rhythmic beat of track and wheel-clicks engulf us. The lights flicker back on and hold as we see a half dozen SOLDIERS in BROWN CAMO, steel- eyed, prepared for whatever may be at the end of the TUNNEL. ZERO IN on TWO: KABLE, 30-something, roughneck... focused, determined; eyes burning with internalized emotion... ... and SANDRA, late 20s, undeniably hot but tough as hell - both are in shackles & cuffs, being roughly transported through underground tunnels, knocked and shoved around. Uniformed GUARDS roam the train, looking pissed off - their swagger seems to mask FEAR. KABLE is meditating, or exhausted - hard to tell. The GIRL makes eye contact w/ him. SANDRA Sandra. KABLE says nothing, just stares at her, stoic. SANDRA (cont'd) My name is Sandra. GUARD Shut the fuck up. Because he can, the GUARD takes a swing at KABLE'S head with a BILLY CLUB... CRACK! (CONTINUED) 2. WHITE KABLE SCRIPT - 9/19/2007 1 CONTINUED: 1 KABLE'S skull snaps back into the window. -

Gender and Race in the Making of Afro-Brazilian Heritage by Jamie Lee Andreson a Dissertation S

Mothers in the Family of Saints: Gender and Race in the Making of Afro-Brazilian Heritage by Jamie Lee Andreson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paul Christopher Johnson, Chair Associate Professor Paulina Alberto Associate Professor Victoria Langland Associate Professor Gayle Rubin Jamie Lee Andreson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1305-1256 © Jamie Lee Andreson 2020 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to all the women of Candomblé, and to each person who facilitated my experiences in the terreiros. ii Acknowledgements Without a doubt, the most important people for the creation of this work are the women of Candomblé who have kept traditions alive in their communities for centuries. To them, I ask permission from my own lugar de fala (the place from which I speak). I am immensely grateful to every person who accepted me into religious spaces and homes, treated me with respect, offered me delicious food, good conversation, new ways of thinking and solidarity. My time at the Bate Folha Temple was particularly impactful as I became involved with the production of the documentary for their centennial celebrations in 2016. At the Bate Folha Temple I thank Dona Olga Conceição Cruz, the oldest living member of the family, Cícero Rodrigues Franco Lima, the current head priest, and my closest friend and colleague at the temple, Carla Nogueira. I am grateful to the Agência Experimental of FACOM (Department of Communications) at UFBA (the Federal University of Bahia), led by Professor Severino Beto, for including me in the documentary process. -

Fade In: Int. Art Gallery – Day

FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY Exhibition Guide FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY March 03 – May 08, 2016 Works by Danai Anesiadou, Nairy Baghramian, Michael Bell-Smith, Dora Budor, Heman Chong, Mike Cooter, Brice Dellsperger, GALA Committee, Mathis Gasser, Jamian Juliano-Villani, Bertrand Lavier, William Leavitt, Christian Marclay, Rodrigo Matheus, Allan McCollum, Henrique Medina, Carissa Rodriguez, Cindy Sherman, Amie Siegel, Scott Stark, and Albert Whitlock; performances and public programs by Casey Jane Ellison, Mario García Torres, Alex Israel, Thirteen Black Cats, and more. Recasting the gallery as a set for dramatic scenes, FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY explores the role that art plays in narrative film and television. FADE IN features the work of 25 artists and considers a history of art as seen in classic movies, soap operas, science fiction, pornography and musicals. These works have been sourced, reproduced and created in response to artworks that have been made to appear on-screen, whether as props, set dressings, plot devices, or character cues. The nature of the exhibition is such that sculptures, paintings and installations transition from prop to image to art object, staging an enquiry into whether these fictional depictions in mass media ultimately have greater influence in defining a collective understanding of art than art itself does. Certain preoccupations with artworks are established early on in cinematic history: the preciousness of art objects anchors their roles as plot drivers, and anxieties intensify regarding the vitality of artworks and their perceived abilities to wield power over viewers or to capture spirits. Such themes were famously explored in the 1945 film adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, from which Cindy Sherman has sourced the original portrait painted for the production. -

Fun in the Outdoors Perfectly Effortless Program

FUN IN THE OUTDOORS Perfectly Effortless Programs Girl Scouts of Eastern Missouri Emerson Resource Center 2300 Ball Drive St. Louis, MO 63146 314.592.2360 Introduction Girl Scout programs are built on the concept of progression – acquiring the skills needed to progress to more difficult or highly-skilled activities. Learning skills that will be helpful in the outdoors can start during any troop meeting and along with a progressive series of trips, beginning with a day outing, can provide the group with the skills to travel almost anywhere. Try looking at It’s Your Planet-Love It! Journey series or check out The Girl Guide to Girl Scouting legacy badges (naturalist) or the outdoor badges- hiker, camper, trailblazer or adventurer. A Day Outing Is: • Cooking, hiking and playing outdoor games • Learning about nature – birds, the trees and the sky • Discovering the beauty of the outdoors • Becoming comfortable in the natural environment • Practicing skills for a first time before an overnight camping trip • Taking an all-day hike to prepare for a backpack trip • Practicing canoe skills for a canoe camping trip • Learning to fish • Finding your way with a compass or geo-caching with a GPS unit • Introducing girls and adults to Council camp facilities • Exploring forests and parks nearby Before you do anything in the outdoors, make sure you are ready: A day outing offers many opportunities for girls to complete badges. Putting the skills they have learned at in-town meetings into practical use is part of the day outing experience. Is there a badge or patch they could work on that would include these activities? Look in The Girl Guide to Girl Scouting for badge requirements.