The Shakespeare Tradition in Philadelphia. 161

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recollections and Reflections, a Professional Autobiography

... • . .... (fcl fa Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO from the estate of MARION WALKER RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS. RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS OF J. E. PLANCHE, (somerset herald). ^ |]rofcssiona( gaifobbcjrapbtr. " I ran it through, even from my boyish days, To the very moment that he bade me tell it." Othello, Act i., Scene 3. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. II. LONDON: TINSLEY BROTHERS, 18, CATHERINE STREET, STRAND. 1872. ..4^ rights reserved. LONDON BRADBURV, EVANS, AND CO., PRINTERS, WHITBFRIAR,-!. ——— CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. VAGK Another Mission to Paris—Production of " Le Domino Noir"— Mr. and Mrs. Charles Gore—Dinner at Lord Lyndhurst's Mons. Allou, Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries of France—The Duke D'Istrie and his Collection of Armour Her Majesty's Coronation—" Royal Records "—Extension of Licence to the Olympic and Adelphi Theatres—" The Drama's Levee"—Trip to Calais with Madame Yestris and Charles Mathews previous to their departure for America—Visit to Tournehem—Sketching Excursion with Charles Mathews Marriage of Madame Vestris and Charles Mathews—They sail for New York—The Olympic Theatre opened under my Direc- tion—Farren and Mrs. Nisbett engaged—Unexpected return of Mr. and Mrs. Mathews—Re-appearance of the latter in " Blue Beard "— " Faint Heart never won Fair Lady "—"The Garrick Fever"—Charles Mathews takes Covent Garden Theatre CHAPTER II. Death of Haynes Bayly—Benefit at Drury Lane for his Widow and Family—Letters respecting it from Theodore Hook and Mrs. Charles Gore—Fortunate Results of the Benefit—Tho Honourable Edmund Byng—Annual Dinner established by him in aid of Thomas Dibdin—Mr. -

Barretto: (--- ) Supported by (--- ) :0 Andmr

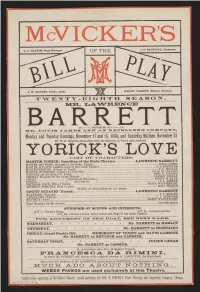

McVICKER'S L. L. SHARPE, Stage Manager. BILL OF THEPLAY C. S. REDFIELD, Treasurer. J. H. ROGERS, Scenic Artist. HENRY DOEHNE, Musical Director. T WENTY-EIGHTH SEASON. MR. LAWRENCE BARRETTO: (--- ) SUPPORTED BY (--- ) :0 ANDMR. LOUISJAMES AN EXCELLENT COMPAN Y. Monday and TuesdayEvenings, November 17 and 18, 1884, and Saturday Matinee, November 22 Mr. W. D. Howell's adaptationfrom the Spanish,in ThreeActs, entitled YORICK'S LOVE CAST OF CHARACTERS: MASTER YORICK, Comedian of the Globe Theatre LAWRENCE BARRETT MASTER HEYWOOD, Manager of the Globe Theatre LOUIS JAMES MASTER WALTON, LeadingActor of the GlobeTheatre S. E. SPRINGER MASTEREDMUND, Protege of Yorick F. C. MOSLEY MASTER WOODFORD, Authorof a NewPlay CHAS M. COLLINS GREGORY, an old servantof YorickBEN G.ROGERS THOMAS, Prompter of the Globe Theatre ALBERT RIDDLE PHILIP } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { PERCY WINTER TOBIAS } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { J. L. FINNEY MISTRESS ALICE, Wife of Yorick } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { MARIE WAINRIGHT MISTRESS DOROTHY, Maid to Alice } Servants of Warrener, the Painter, { ROSA FRANCE CHANGE OF CHARACTERS IN ACT THIRD. COUNT OCTAVIO (Yorick) LAWRENCE BARRETT MANFREDO (Edmund) F. C. MOSLEY LANDOLPHO (Walton) S. E. SPRINGER BEATRICE (Alice) MARIE WAINWRIGHT Stage Manager for Mr. Barrett OLIVER DOUD SYNOPSIS OF SCENES AND INCIDENTS: ACT I.-Yorick's Home. ACT II.-Yorick's Garden. ACTIII.—Scenes 1 and 2—Green Room and Stage of old GlobeTheatre. FOR ARGUMENT OF THE PLAY, SEE NEXT PAGE. WEDNESDAY, Mr. BARRETT as HAMLET THURSDAY, Mr. BARRETT as RICHELIEU FRIDAY, Grand Double Bill, MERCHANTOF VENICE and DAVID GARRICK Mr. BARRETT- as SHYLOCK and GARRICK. SATURDAYNIGHT, JULIUS CAESAR Mr. -

The Tragedy of King Richard the Third. Edited by A. Hamilton Thompson

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/3edtragedyofking00shakuoft OFC 1 5 iqo? THE ARDEN SHAKESPEARE W. GENERAL EDITOR: J. CRAIG 1899-1906: R. H. CASE, 1909 THE TRAGEDY OF KING RICHARD THE THIRD *^ ^*^ THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF KING RICHARD THE THIRD EDITED BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON . ? ^^ METHUEN AND CO. LTD. 86 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON Thircf Edition First Published . August 22nd igoy Second Edition . August ^9^7 Third Edition . igi8 CONTENTS PAGB Introduction vii The Tragedy of King Richard the Third ... 7 Appendix I. 211 Appendix II 213 Appendix III. ......... 215 Appendix IV 220 " INTRODUCTION Six quarto editions of The Life and Death of Richard III. were published before the appearance of the folio of 1623. The title of the first quarto is : TRAGEDY OF King Richard THE | the third. Containing, His treacherous Plots against his | | brother Clarence: the pittiefull murther of his innocent | nephewes : his tyrannicall vsurpation : with the whole course | | of his detested life, and most deserued death. As it hath beene | lately the Right honourable the Chamber- Acted by | Lord | laine his seruants. [Prijnted by Valentine Sims, | At LONDON | for Wise, dwelling in Paules Chuch-yard \sic\ at Andrew | Signe of the Angell. the | 1597. I In the title of the second quarto (i 598), printed for Wise by Thomas Creede, the words " By William Shake-speare " occupy a new line after " seruants." The fourth, fifth, and sixth quartos also spell the author's name with a hyphen. The third quarto (1602), also printed by Creede, gives it as "Shakespeare," and adds, in a line above, the words " Newly augmented followed by a comma, which appear in the titles of the re- maining quartos. -

15/7/39 Liberal Arts and Sciences Department of English Charles H

The materials listed in this document are available for research at the University of Record Series Number Illinois Archives. For more information, email [email protected] or search http://www.library.illinois.edu/archives/archon for the record series number. 15/7/39 Liberal Arts and Sciences Department of English Charles H. Shattuck Papers, 1929, 1937-92 CONTENTS Box Correspondence, A-Z, 1944-61 1 Correspondence, A-Z, 1961-92 2-6 Subject File, A-W, 1929, 1946-91 6-10 Accent File, A-W, 1942-79 10 Shattuck Promptbooks, 1942-77 10-14 Playbills, 1913-88 14-15 Publications & Reviews, 1938-86 15-16 Research Notes & Correspondence, 1937-92 Macready & Booth 16-17 Shakespeare Promptbooks 17-21 Shakespeare on the American Stage 21-22 Theatre and Brecht 23 Posters & Slides 24 Box 1: Correspondence, 1944-61 A, 1946-58 Adams, John C. 1945-58, 1960 B, 1947-60 Brecht, Bertolt, 1955 C, 1947-60 D, 1946-59 E, 1946-60 Engle, Paul, 1946-56 F, 1945-60 Ford Foundation, W. McNeil Lowry, 1958-59 G, 1945-60 Gregor, Arthur, 1951-54 H, 1943-60 Harrison, G.B., 1957-58 Hewitt, Barnard, 1947-56 Hanson, Philip, 1951-57 I-K, 1942, 1947-61 L, 1946-60 M, 1944-61 15/7/39 2 N-O, 1949-60 P, 1949-60 Q, 1958-60 R, 1944-64 Sa-Sh, 1948-61 Sl-Sy, 1943-60 Stoddard, Margaret, 1954-55 Swanson, John Wesley, 1946-59 T, 1946-60 U-V, 1948-61 Vassar College, 1948-49 W, 1946-60 Wallace, Karl, 1947-49 X-Z, 1953-59 Box 2: Correspondence, 1961-92 A, 1961-92 Abou-Saif, Laila, 1964-69, 1978 Adams, John C., 1961-85 Andrews, John F., 1976-91 Andrews, Kenneth R., 1963-91 Archer, Stephen, -

[, F/ V C Edna Hammer Cooley 1986 APPROVAL SHEET

WOMEN IN AMERICAN THEATRE, 1850-1870: A STUDY IN PROFESSIONAL EQUITY by Edna Hammer Cooley I i i Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland in parti.al fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ~ /, ,, ·' I . 1986 I/ '/ ' ·, Cop~ I , JI ,)() I co uI (~; 1 ,[, f/ v c Edna Hammer Cooley 1986 APPROVAL SHEET Title of Dissertation: Women in American Theatre, 1850-1870: A Study in Professional Equity Name of Candidate: Edna Hammer Cooley Doctor of Philosophy, 1986 Dissertation and Approved: Dr. Roger Meersman Professor Dept. of Communication Arts & Theatre Date Approved: .;;Jo .i? p ,vt_,,/ /9Y ,6 u ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: Women in American Theatre, 1850- 1870~ A Study_ in Professional Equi!:Y Edna Hammer Cooley, Doctor of Philosophy, 1986 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Roger Meersman Professor of Communication Arts and Theatre Department of Communication Arts and Theatre This study supports the contention that women in the American theatre from 1850 to 1870 experienced a unique degree of professional equity with men in the atre. The time-frame has been selected for two reasons: (1) actresses active after 1870 have been the subject of several dissertations and scholarly studies, while relatively little research has been completed on women active on the American stage prior to 1870, and (2) prior to 1850 there was limited theatre activity in this country and very few professional actresses. A general description of mid-nineteenth-century theatre and its social context is provided, including a summary of major developments in theatre in New York and other cities from 1850 to 1870, discussions of the star system, the combination company, and the mid-century audience. -

Broadside Read- a Brief Chronology of Major Events in Trous Failure

NEWSLETTER OF THE THEATRE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Volume 17, Number 1/Volume 17, Number 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE Summer/Fa111989 EXHIBITION SURVEYS MANHATTAN'S EARLY THEATRE HISTORY L An exhibition spotlighting three early New York theatres was on view in the Main I Gallery of The New York Public Library at Lincoln Center from February 13, 1990 through March 31, 1990. Focusing on the Park Theatre on Park Row, Niblo's Garden on Broadway and Prince Street, and Wal- lack's, later called the Star, on Broadway and 13th Street, the exhibition attempted to show, through the use of maps, photo- graphic blowups, programs and posters, the richness of the developing New York theatre scene as it moved northward from lower Manhattan. The Park Theatre has been called "the first important theatre in the United States." It opened on January 29, 1798, across from the Commons (the Commons is now City Hall Park-City Hall was built in 1811). The opening production, As You Like It, was presented with some of the fin- est scenery ever seen. The theatre itself, which could accommodate almost 2,000, was most favorably reviewed. It was one of the most substantial buildings erected in the city to that date- the size of the stage was a source of amazement to both cast and audience. In the early nineteenth century, to increase ticket sales, manager Stephen Price introduced the "star sys- tem" (the importation of famous English stars). This kept attendance high but to some extent discouraged the growth of in- digenous talent. In its later days the Park was home to a fine company, which, in addition to performing the classics, pre- sented the work of the emerging American playwrights. -

The Routledge Companion to African American Theatre and Performance

The Routledge Companion to African American Theatre and Performance Edited by Kathy A. Perkins, Sandra L. Richards, Renée Alexander Craft , and Thomas F. DeFrantz First published 2009 ISBN 13: 978-1-138-72671-0 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978-1-315-19122-5 (ebk) Chapter 20 Being Black on Stage and Screen Black actor training before Black Power and the rise of Stanislavski’s system Monica White Ndounou CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 124 125 Being Black on stage and screen Worth’s Museum, the All- Star Stock Company was the fi rst professional Black stock company and training school for African American performers (Peterson, “Profi les” 70– 71). Cole’s institution challenged popular perceptions of Black performers as “natural actors” 20 lacking intellect and artistry (Ross 239). Notable performers in the company demonstrated expertise in stage management, producing, directing, playwriting, songwriting, and musical composition. They did so while immersed in the study of voice and vocal music (i.e. opera); BEING BLACK ON STAGE movement through dance (i.e. the cakewalk); comedy, including stand-up and ensemble work in specialty acts (i.e. minstrelsy), and character acting. Examples of the performance styles AND SCREEN explored at the All- Star Stock Company include The Creole Show (1890–1897), the Octoroons Company (1895– 1900), the Black Patti Troubadours (1896– 1915), the Williams and Walker Company (1898– 1909), and the Pekin Stock Company (1906– 1911), which performed Black Black actor training before Black Power musicals and popular comedies (Peterson, “Directory” 13). Some of the Pekin’s players were and the rise of Stanislavski’s system also involved in fi lm, like William Foster, who is generally credited as the fi rst Black fi lm- maker ( The Railroad Porter , 1912) (Robinson 168–169). -

Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama James Armstrong The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2317 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] FIT FOR THE STAGE: REGENCY ACTORS AND THE INSPIRATION BEHIND ROMANTIC DRAMA by JAMES ARMSTRONG A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 ii © 2017 JAMES ARMSTRONG All Rights Reserved iii Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama by James Armstrong This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. May 12, 2017 ______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Marvin Carlson Distinguished Professor May 12, 2017 ______________________________ Date Executive Officer Peter Eckersall Professor ______________________________ Jean Graham-Jones Professor ______________________________ Annette J. Saddik Professor Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract Fit for the Stage: Regency Actors and the Inspiration Behind Romantic Drama by James Armstrong Adviser: Distinguished Professor Marvin Carlson In this dissertation, I argue that British verse tragedies of the Romantic era must be looked at not as "closet dramas" divorced from the stage, but as performance texts written with specific actors in mind. -

CYMBELINE" in the Fllii^Slhi TI CENTURY

"CYMBELINE" IN THE fllii^SLHi TI CENTURY Bennett Jackson Submitted in partial fulfilment for the de ree of uaster of Arts in the University of Birmingham. October 1971. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. SYNOPSIS This thesis consists of an Introduction, followed by Part I (chapters 1-2) in which nineteenth- century criticism of the play is discussed, particular attention being paid to Helen Faucit's essay on Imogen, and its relationship to her playing of the role. In Part II the stags-history of Oymbcline in London is traced from 1785 to Irving's Lyceum production of 1896. Directions from promptbooks used by G-.P. Cooke, W.C. Macready, Helen Eaucit, and Samuel ±helps are transcribed and discussed, and in the last chapter the influence of Bernard Shaw on Ellen Terry's Imogen is considered in the light of their correspondence and the actress's rehearsal copies of the play. There are three appendices: a list of performances; transcriptions of two newspaper reviews (from 1843 and 1864) and one private diary (Gordon Crosse's notes on the Lyceum Gymbeline); and discussion of one of the promptbooks prepared for Charles Kean's projected production. -

The Mammoth Cave ; How I

OUTHBERTSON WHO WAS WHO, 1897-1916 Mails. Publications : The Mammoth Cave ; D'ACHE, Caran (Emmanuel Poire), cari- How I found the Gainsborough Picture ; caturist b. in ; Russia ; grandfather French Conciliation in the North of Coal ; England ; grandmother Russian. Drew political Mine to Cabinet ; Interviews from Prince cartoons in the "Figaro; Caran D'Ache is to Peasant, etc. Recreations : cycling, Russian for lead pencil." Address : fchological studies. Address : 33 Walton Passy, Paris. [Died 27 Feb. 1909. 1 ell Oxford. Club : Koad, Oxford, Reform. Sir D'AGUILAR, Charles Lawrence, G.C.B ; [Died 2 Feb. 1903. cr. 1887 ; Gen. b. 14 (retired) ; May 1821 ; CUTHBERTSON, Sir John Neilson ; Kt. cr, s. of late Lt.-Gen. Sir George D'Aguilar, 1887 ; F.E.I.S., D.L. Chemical LL.D., J.P., ; K.C.B. d. and ; m. Emily, of late Vice-Admiral Produce Broker in Glasgow ; ex-chair- the Hon. J. b. of of School Percy, C.B., 5th Duke of man Board of Glasgow ; member of the Northumberland, 1852. Educ. : Woolwich, University Court, Glasgow ; governor Entered R. 1838 Mil. Sec. to the of the Glasgow and West of Scot. Technical Artillery, ; Commander of the Forces in China, 1843-48 ; Coll. ; b. 13 1829 m. Glasgow, Apr. ; Mary served Crimea and Indian Mutiny ; Gen. Alicia, A. of late W. B. Macdonald, of commanding Woolwich district, 1874-79 Rammerscales, 1865 (d. 1869). Educ. : ; Lieut.-Gen. 1877 ; Col. Commandant School and of R.H.A. High University Glasgow ; Address : 4 Clifton Folkestone. Coll. Royal of Versailles. Recreations: Crescent, Clubs : Travellers', United Service. having been all his life a hard worker, had 2 Nov. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of com puter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI EDWTN BOOTH .\ND THE THEATRE OF REDEMPTION: AN EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF JOHN WTLKES BOOTH'S ASSASSINATION OF ABRAHANI LINCOLN ON EDWIN BOOTH'S ACTING STYLE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael L. -

Appendix: Famous Actors/ Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom's Cabin

A p p e n d i x : F a m o u s A c t o r s / Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom’s Cabin Uncle Tom Ophelia Otis Skinner Mrs. John Gilbert John Glibert Mrs. Charles Walcot Charles Walcott Louisa Eldridge Wilton Lackaye Annie Yeamans David Belasco Charles R. Thorne Sr.Cassy Louis James Lawrence Barrett Emily Rigl Frank Mayo Jennie Carroll John McCullough Howard Kyle Denman Thompson J. H. Stoddard DeWolf Hopper Gumption Cute George Harris Joseph Jefferson William Harcourt John T. Raymond Marks St. Clare John Sleeper Clarke W. J. Ferguson L. R. Stockwell Felix Morris Eva Topsy Mary McVicker Lotta Crabtree Minnie Maddern Fiske Jennie Yeamans Maude Adams Maude Raymond Mary Pickford Fred Stone Effie Shannon 1 Mrs. Charles R. Thorne Sr. Bijou Heron Annie Pixley Continued 230 Appendix Appendix Continued Effie Ellsler Mrs. John Wood Annie Russell Laurette Taylor May West Fay Bainter Eva Topsy Madge Kendall Molly Picon Billie Burke Fanny Herring Deacon Perry Marie St. Clare W. J. LeMoyne Mrs. Thomas Jefferson Little Harry George Shelby Fanny Herring F. F. Mackay Frank Drew Charles R. Thorne Jr. Rachel Booth C. Leslie Allen Simon Legree Phineas Fletcher Barton Hill William Davidge Edwin Adams Charles Wheatleigh Lewis Morrison Frank Mordaunt Frank Losee Odell Williams John L. Sullivan William A. Mestayer Eliza Chloe Agnes Booth Ida Vernon Henrietta Crosman Lucille La Verne Mrs. Frank Chanfrau Nellie Holbrook N o t e s P R E F A C E 1 . George Howard, Eva to Her Papa , Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture . http://utc.iath.virginia.edu {*}.