Historic-District-Old-City.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief History of Architecture in N.C. Courthouses

MONUMENTS TO DEMOCRACY Architecture Styles in North Carolina Courthouses By Ava Barlow The judicial system, as one of three branches of government, is one of the main foundations of democracy. North Carolina’s earliest courthouses, none of which survived, were simple, small, frame or log structures. Ancillary buildings, such as a jail, clerk’s offi ce, and sheriff’s offi ce were built around them. As our nation developed, however, leaders gave careful consideration to the structures that would house important institutions – how they were to be designed and built, what symbols were to be used, and what building materials were to be used. Over time, fashion and design trends have changed, but ideals have remained. To refl ect those ideals, certain styles, symbols, and motifs have appeared and reappeared in the architecture of our government buildings, especially courthouses. This article attempts to explain the history behind the making of these landmarks in communities around the state. Georgian Federal Greek Revival Victorian Neo-Classical Pre – Independence 1780s – 1820 1820s – 1860s 1870s – 1905 Revival 1880s – 1930 Colonial Revival Art Deco Modernist Eco-Sustainable 1930 - 1950 1920 – 1950 1950s – 2000 2000 – present he development of architectural styles in North Carolina leaders and merchants would seek to have their towns chosen as a courthouses and our nation’s public buildings in general county seat to increase the prosperity, commerce, and recognition, and Trefl ects the development of our culture and history. The trends would sometimes donate money or land to build the courthouse. in architecture refl ect trends in art and the statements those trends make about us as a people. -

Common Heritage Совместное Наследие

COMMON HERITAGE СОВМЕСТНОЕ НАСЛЕДИЕ The multicultural heritage of Vyborg and its preservation Мультикультурное наследие Выборга и его сохранение COMMON HERITAGE СОВМЕСТНОЕ НАСЛЕДИЕ The multicultural heritage of Vyborg and its preservation Proceedings of the international seminar 13.–14.2.2014 at The Alvar Aalto library in Vyborg Мультикультурное наследие Выборга и его сохранение Труды мeждународного семинара 13.–14.2.2014 в Центральной городской библиотеке А. Аалто, Выборг Table of contents Оглавление Editor Netta Böök FOREWORD .................................................................6 Редактор Нетта Бёэк ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ Graphic design Miina Blot Margaretha Ehrström, Maunu Häyrynen: Te dialogical landscape of Vyborg .....7 Графический дизайн Мийна Блот Маргарета Эрстрëм, Мауну Хяйрюнен: Диалогический ландшафт Выборга Translations Gareth Grifths and Kristina Kölhi / Gekko Design; Boris Sergeyev Переводы Гарет Гриффитс и Кристина Кëлхи / Гекко Дизайн; Борис Сергеев Publishers The Finnish National Committee of ICOMOS (International Council for Monuments and Sites) and OPENING WORDS The Finnish Architecture Society ..........................................................12 Издатели Финляндский национальный комитет ИКОМОС (Международного совета по сохранению ВСТУПИТЕЛЬНЫЕ СЛОВА памятников и достопримечательных мест) и Архитектурное общество Финляндии Maunu Häyrynen: Opening address of the seminar ............................15 Printed in Forssa Print Мауну Хяйрюнен: Вступительное обращение семинара Отпечатано в типографии Forssa Print -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2020 Executive Order 13967

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2020 Executive Order 13967—Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture December 18, 2020 By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered as follows: Section 1. Purpose. Societies have long recognized the importance of beautiful public architecture. Ancient Greek and Roman public buildings were designed to be sturdy and useful, and also to beautify public spaces and inspire civic pride. Throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, public architecture continued to serve these purposes. The 1309 constitution of the City of Siena required that "[w]hoever rules the City must have the beauty of the City as his foremost preoccupation . because it must provide pride, honor, wealth, and growth to the Sienese citizens, as well as pleasure and happiness to visitors from abroad." Three centuries later, the great British Architect Sir Christopher Wren declared that "public buildings [are] the ornament of a country. [Architecture] establishes a Nation, draws people and commerce, makes the people love their native country . Architecture aims at eternity[.]" Notable Founding Fathers agreed with these assessments and attached great importance to Federal civic architecture. They wanted America's public buildings to inspire the American people and encourage civic virtue. President George Washington and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson consciously modeled the most important buildings in Washington, D.C., on the classical architecture of ancient Athens and Rome. They sought to use classical architecture to visually connect our contemporary Republic with the antecedents of democracy in classical antiquity, reminding citizens not only of their rights but also their responsibilities in maintaining and perpetuating its institutions. -

View the Program Book

PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 AWARDS ACHIEVEMENT PRESERVATION e join eas us pl in at br ing le e c 1996 2021 p y r e e e a c s rs n e a rv li ati o n al 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS WEDNESDAY, JUNE 9, 2021 CONGRATULATIONS TO THE 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARD HONOREES Your knowledge, commitment, and advocacy create a better future for our city. And best wishes to the Preservation Alliance as you celebrate 25 years of invaluable service to the Greater Philadelphia region. pmcpropertygroup.com 1 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 WELCOME TO THE 2021 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS HONORING THE INDIVIDUALS, ORGANIZATIONS, BUSINESSES, AND PROJECTS THROUGHOUT GREATER PHILADELPHIA THAT EXEMPLIFY OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Our Sponsors . 4 Executive Director’s Welcome . .. 6 Board of Directors . 8 Celebrating 25 Years: A Look Back . 9 Special Recognition Awards . 11 Advisory Committee. 11 James Biddle Award . 12 Board of Directors Award . 13 Rhoda and Permar Richards Award. 13 Economic Impact Award . 14 Preservation Education Awards . 14-15 John Andrew Gallery Community Action Awards . 15-16 Public Service Awards . 16-17 Young Friends of the Preservation Alliance Award . 17 AIA Philadelphia Henry J . Magaziner Award . .. 18 AIA Philadelphia Landmark Building Award . .. 18 Members of the Grand Jury . .. 19 Grand Jury Awards and Map . 20 In Memoriam . 46 Video by Mitlas Productions LLC | Graphic design by Peltz Creative Program editing by Fabien Communications 25TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE PRESERVATION ALLIANCE FOR GREATER PHILADELPHIA 2 3 PRESERVATION ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS 2021 OUR SPONSORS ALABASTER PMC Property Group Brickstone IBEW Local Union 98 Post Brothers MARBLE A. -

Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: an Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1992 Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991) Frederick Lee Richards University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Richards, Frederick Lee, "Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991)" (1992). Theses (Historic Preservation). 349. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/349 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Richards, Frederick Lee (1992). Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991). (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/349 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991) Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Richards, Frederick Lee (1992). Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: -

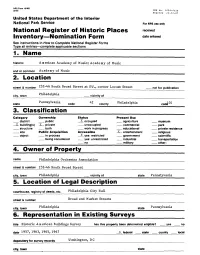

Academy of Music; Academy of Music_____ and Or Common Academy of Music______2

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) 0MB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_________________ 1. Name___________________ historic______American Academy of Music; Academy of Music_____ and or common Academy of Music_______________________ 2. Location_________________ street & number 232-46 South Broad Street at SW., corner Locust Street not for publication Philadelphia city, town vicinity of P ennsylvania 42 county Philadelphia state code CO 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum _ K- building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition, Accessible X entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered - yes: unrestricted __ industrial transportation .... no military __ other: 4. Owner of Property name Philadelphia Orchestra Association street & number 232-46 South Broad Street city, town Philadelphia vicinity of state Pennslyvania 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Philadelphia City Hall street & number Broad and Market Streets city, town Philadelphia state Pennsylvania 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Historic American Buildings Survey has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1957, 1963, 1965, 1967 JL federal state county local depository for survey records W ashing ton, D C city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered ^ original site good ruins X altered moved date fair unexposed Interior Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance This free standing brick Renaissance Revival Style building exhibits a free use of classical forms. -

Plate I. Liverpool Castle

PLATE I. LIVERPOOL CASTLE. RESTORED FROM AUTHENTIC PLANS AMD MEASUREMENTS BY EDWARD W. COX. AN ATTEMPT TO RECOVER THE PLANS OF THE CASTLE OF LIVERPOOL FROM AUTHENTIC RECORDS; CONSIDERED IN CONNEXION WITH MEDI/EVAL PRINCIPLES OF DEFENCE AND CON STRUCTION. By Edward W. Cox. (Read 6di November, 1890.) DESCRIPTION OF THE FEATURES AND BUILDINGS OF THE CASTLE. T TPON a rock}'knoll, washed by the Mersey on its V_J western side, and cut off from the mainland on the south and east by the tidal waters of the old Pool, forming the estuary of a small stream falling from the Moss Lake that lay in a fold of the Great Heath, at the foot of the hills which environ the town on the east, was built the Castle of Liverpool. The rocky platform on which it stood sloped westward towards the river, and was approached only from the north. About the centre of the promontory, and commanding its area and shores on every side, the castle was set on the highest point, and was defended by a ditch cut in the rock, varying from 30 to 40 feet in width, and from 24 to 30 feet in depth. Beyond this ditch to the northward, earth works were thrown across the peninsula, and from O 2 ig6 Liverpool Castle. notices in early records of the herbage on these defences, they seemed to have formed a line of outworks surrounding the castle. From the western side of the rock-cut ditch, which formed the castle's second line of defence, near the northern corner, an underground passage, ten feet high, was cut in the rock down to the shore of the Mersey, which still exists below the pave ment of James Street, and was seen by the writer when it was opened some thirty years since. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Hamburg Historic District (amendment, increase, decrease) other names/site number Gold Coast 2. Location th hill to northwest of downtown: roughly W. 5 St from Western to N/A street & number Brown, W. 6th St from Harrison to Warren, W. 7th St from Ripley to not for publication th th Vine, W. 8 St from Ripley to Vine, W. 9 St from Ripley to Brown N/A city or town Davenport vicinity state Iowa code IA county Scott code 163 zip code 52802 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

The “Trenton in 1775” Mapping Project City of Trenton, Mercer County, New Jersey 1714 1781

THE “TRENTON IN 1775” MAPPING PROJECT CITY OF TRENTON, MERCER COUNTY, NEW JERSEY THE TRENTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY FUNDED BY: THE NEW JERSEY HISTORICAL COMMISSION Prepared by: Hunter Research, Inc. 1781 1714 120 West State Street Trenton, NJ 08608 www.hunterresearch.com Cheryl Hendry, Historian Marjan Osman, Graphic Specialist Damon Tvaryanas, Principal Historian/Architectural Historian Richard Hunter, Principal THE “TRENTON IN 1775” MAPPING PROJECT, CITY OF TRENTON, MERCER COUNTY, NEW JERSEY INTRODUCTION From the standpoint of geographic coverage, the County prior to the formation of Hunterdon County project focused on the historic core of the down- in 1714. The various deeds referenced in these A small cache of colonial manuscripts, includ- The purpose of this project, as expressed in a propos- town on the north side of the Assunpink Creek, an indexes are available on microfilm at the New ing several unrecorded deeds, was located in the al provided by Hunter Research, Inc. to the Trenton area bounded approximately by Petty’s Run on the Jersey State Archives. These documents, typically Trentoniana Collection of the Trenton Public Historical Society in August, 2006, is to develop “a west, the Trenton Battle Monument to the north referenced as “West Jersey Deeds,” were systemati- Library. These materials, totaling approximately detailed map of property ownership and land use for and Montgomery Street on the east. As described cally reviewed and copies printed for those proper- 25 documents of interest, were also systematically downtown Trenton north of the Assunpink Creek in greater detail below, the archival research con- ties within or close to the area of study. -

City of Wauwatosa, Wisconsin

City of Wauwatosa, Wisconsin Architectural and Historical Intensive Survey Report of Residential Properties Phase 2 By Rowan Davidson, Associate AIA & Jennifer L. Lehrke, AIA, NCARB Legacy Architecture, Inc. 605 Erie Avenue, Suite 101 Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081 Project Director Joseph R. DeRose, Survey & Registration Historian Wisconsin Historical Society Division of Historic Preservation – Public History 816 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 Sponsoring Agency Wisconsin Historical Society Division of Historic Preservation – Public History 816 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 2019-2020 Acknowledgments This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to Office of the Equal Opportunity, National Park Service, 1849 C Street NW, Washington, DC 20240. The activity that is the subject of this intensive survey report has been financed entirely with Federal Funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, and administered by the Wisconsin Historical Society. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the Wisconsin Historical Society, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the Wisconsin Historical Society. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

Historic-Register-OPA-Addresses.Pdf

Philadelphia Historical Commission Philadelphia Register of Historic Places As of January 6, 2020 Address Desig Date 1 Desig Date 2 District District Date Historic Name Date 1 ACADEMY CIR 6/26/1956 US Naval Home 930 ADAMS AVE 8/9/2000 Greenwood Knights of Pythias Cemetery 1548 ADAMS AVE 6/14/2013 Leech House; Worrell/Winter House 1728 517 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 519 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 600-02 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 2013 601 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 603 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 604 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 605-11 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 606 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 608 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 610 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 612-14 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 613 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 615 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 616-18 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 617 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 619 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 629 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 631 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 1970 635 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 636 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 637 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 638 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 639 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 640 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 641 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 642 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 643 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 703 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 708 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 710 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 712 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 714 ADDISON ST Society Hill