Submission to the Productivity Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sacrificing Steve

Cultural Studies Review volume 16 number 2 September 2010 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index pp. 179–93 Luke Carman 2010 Sacrificing Steve How I Killed the Crocodile Hunter LUKE CARMAN UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY There has been a long campaign claiming that in a changed world and in a changed Australia, the values and symbols of old Australia are exclusive, oppressive and irrelevant. The campaign does not appear to have succeeded.1 Let’s begin this paper with a peculiar point of departure. Let’s abjure for the moment the approved conventions of academic discussion and begin not with the obligatory expounding of some contextualising theoretical locus, but instead with an immersion much more personal. Let’s embrace the pure, shattering honesty of humiliation. Let’s begin with a tale of shame and, for the sake of practicality, let’s make it mine. Early in September 2006, I was desperately trying to finish a paper on Australian representations of masculinity. The deadline had crept up on me, and I was caught struggling for a focusing point. I wanted a figure to drape my argument upon, one that would fit into a complicated and altogether shaky coagulation of ideas surrounding Australian icons, legends and images—someone who perfectly ISSN 1837-8692 straddled an exploration of masculine constructions within a framework of cringing insecurities and historical silences. I could think of men, I could think of iconic men, and I could think of them in limitless abundance, but none of them encapsulated everything I wanted to say. -

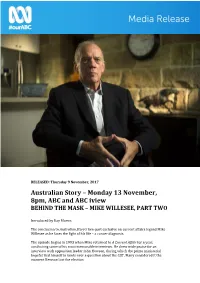

Australian Story – Monday 13 November, 8Pm, ABC and ABC Iview BEHIND the MASK – MIKE WILLESEE, PART TWO

RELEASED: Thursday 9 November, 2017 Australian Story – Monday 13 November, 8pm, ABC and ABC iview BEHIND THE MASK – MIKE WILLESEE, PART TWO Introduced by Ray Martin. The conclusion to Australian Story’s two-part exclusive on current affairs legend Mike Willesee as he faces the fight of his life – a cancer diagnosis. The episode begins in 1993 when Mike returned to A Current Affair for a year, conducting some of his most memorable interviews. He drew wide praise for an interview with opposition leader John Hewson, during which the prime ministerial hopeful tied himself in knots over a question about the GST. Many considered it the moment Hewson lost the election. Four weeks later praise turned to condemnation when Mike interviewed two young children held captive by killers during the Cangai siege. “I think this is a classic case where we misjudged the audience reaction,” admits former Nine news chief Peter Meakin. Tiring of nightly current affairs, Mike turned his attention to a variety of business interests and documentary making. While in Kenya on his way to film in Sudan he had a premonition that the small plane he was boarding would crash. Shortly after take-off, it did. Although Mike was unhurt, the experience had a profound impact on him and led him on a long journey back to the Catholic faith of his childhood. In the years since he has invested much of his time into trying to find scientific proof for various religious miracles. It is Mike’s strong religious faith, along with the support of his family, that has helped him since being diagnosed with cancer in October last year. -

Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Annual Report Board of Directors Cruising Yacht Club of Australia

07/08 Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Annual Report Board of Directors Cruising Yacht Club Of Australia Matt Allen Garry Linacre Michael Cranitch Alan Green Commodore Vice Commodore Rear Commodore Rear Commodore Paul Billingham John Cameron Richard Cawse Geoff Cropley Treasurer Director Director Director Howard Piggott Rod Skellet Graeme Wood Director Director Director 2 Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Annual Report: Year end 31 March 2008 Contents Board of Directors, Management and Sub-Committees 2 Membership, Life Members, Past Commodores & Obituary 3 Commodore’s Report 4 Treasurer’s Report 6 Sailing Committee Report 8 Audit, Planning & Risk Committee Report 10 Cruising Committee Report 11 Training & Development Committee Report 12 Marina & Site Committee Report 14 Member Services Committee Report 15 Associates Committee Report 16 Archives Committee Report 18 Directors’ Report 19 Independent Audit Report 22 Directors’ Declaration 23 Auditor’s Independence Declaration 24 Income Statement 25 Balance Sheet 26 Statement of Recognised Income & Expense 27 Notes to the Financial Statements 28 Supplementary Information 44 Members List 45 Yacht Register 58 CruisingCruising Yacht Yacht Club Club of Australiaof Australia 11 Photography : Rolex, Andrea Francolini, CYCA Staff AnnualAnnual Report: Report: Year Year end end 31 31March March 2008 2008 Board of Directors, Management & Sub-Committees 2007 - 2008 Board of Directors Sub-Committees Commodore Archives M. Allen R. Skellet (Chairman), B. Brenac, T. Cable, A. Campbell, D. Colfelt, J. Keelty, B. Psaltis, P. Shipway, G. Swan, Vice Commodore M.& J. York. G. Linacre Associates Rear-Commodores P. Messenger (President), P. Brinsmead, E. Carpenter, M. Cranitch, A. Green J. Dahl, F. Davies, P. Emerson, K. -

Australian Story – Monday 6 November, 8Pm, ABC and ABC Iview BEHIND the MASK – MIKE WILLESEE

RELEASED: Thursday 2 November, 2017 Australian Story – Monday 6 November, 8pm, ABC and ABC iview BEHIND THE MASK – MIKE WILLESEE An inimitable presence on our TV screens for 50 years, Mike Willesee now faces his greatest challenge – a diagnosis of throat cancer. In a two-part exclusive, Australian Story looks back over the extraordinary life of one of broadcasting’s more enigmatic characters. Born in Perth, Mike was profoundly influenced by the family’s strong Catholic faith and his father’s involvement in politics. “I went to John Curtin’s funeral and I sat on Ben Chifley’s knee and Gough Whitlam watched me play football so I guess by osmosis if nothing else I was learning about politics,” Mike says. As a 10-year-old, Mike was sent briefly to the notorious Bindoon Boy’s Town by his father in order to toughen him up. It was a brutal experience. “I still don't know why my father thought I needed to toughen up,” Mike says, “but I did toughen up. You know, it changed me.” Later, a split within the Labor party saw the family ostracised by the Catholic church. His father was railed against from the pulpit and Mike was forced out of school a year early by the Catholic brothers who taught him. These events, and an emerging interest in girls, saw Mike turn his back on the church. After school, Mike fell into journalism, working for papers in Perth and Melbourne before ending up in Canberra. When the ABC launched the ground- breaking current affairs program This Day Tonight, he found himself in the right place at the right time. -

The Naked Surgeon the Power and Peril of Transparency in Medicine

JULY 2015 POPULAR SCIENCE / HEALTH Giulia Enders Gut translated by the inside story of our body’s most under-rated organ David Shaw The key to living a happier, healthier life is inside us. Our gut is almost as important to us as our brain or our heart, yet we know very little about how it works. In Gut, Giulia Enders shows that rather than the utilitarian and — let’s be honest — somewhat embarrassing body part we imagine it to be, it is one of the most complex, important, and even miraculous parts of our anatomy. And scientists are only just discovering quite how much it has to offer; new research shows that gut bacteria can play a role in everything from obesity and allergies to Alzheimer’s. Beginning with the personal experience of illness that inspired her research, and going on to explain everything from the basics of nutrient absorption to the GIULIA ENDERS is a two-time latest science linking bowel bacteria with depression, scholarship winner of the Enders has written an entertaining, informative health Wilhelm Und Else Heraeus handbook. Gut definitely shows that we can all benefit Foundation, and is doing from getting to know the wondrous world of our inner research for her medical workings. doctorate at the Institute for Microbiology in Frankfurt. In this charming book, young scientist Giulia Enders In 2012, her presentation of takes us on a fascinating tour of our insides. Her Gut won her first prize at the message is simple — if we treat our gut well, it will treat Science Slam in Berlin, and us well in return. -

A Cause for Animation: Harry Reade and the Cuban Revolution

A cause for animation: Harry Reade and the Cuban Revolution Max Bannah This thesis is submitted in the Visual Arts Department, Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology, in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts (Research), February 2007. Abstract This monographic study examines the life of the Australian artist Harry Reade (19271998), and his largely overlooked contribution to animation within historical, social, political and cultural contexts of his time. The project constitutes a biography of Reade, tracing his life from his birth in 1927 through to his period of involvement with animation between 1956 and 1969. The biography examines the forces that shaped Reade and the ways in which he tried to shape his world through the medium of animation. It chronicles his experiences as a child living in impoverished conditions during the Great Depression, his early working life, the influence of left wing ideology on his creative development, and his contribution to animation with the Waterside Workers’ Federation Film Unit, in Sydney. The study especially focuses on the period between 1961 and 1969 during which Reade supported the Cuban Revolution’s social and cultural reform process by writing and directing animated films at the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (Cuban Institute of the Art and Industry of Cinema – ICAIC), in Havana. The thesis argues that Reade played a significant role in the development of Cuban animation during the early years of the Cuban Revolution. Further, his animated work in this cultural sphere was informed by a network of political alliances and social philosophies that were directly linked to his experiences and creative development in Australia. -

Plaque Unveiling for Alan Morris, 24 February 2021 Speech by Business

Plaque unveiling for Alan Morris, 24 February 2021 Speech by business partner and co-founder of Mojo, Allan Johnston1 120½ Underwood Street …Our happiest and most successful years were here. Mo would be chuffed to have his plaque right here … we both loved the place. John Singleton owned the building, and still does … he had his SPASM agency here before us. I first met Mo when he was the creative director at Mullins Clarke and Ralph where he had won a Caxton Award for his print work for Jaguar. It was the seventies and a lot of creative people were tired of the formal structure of established ad agencies and decided being freelance would mean more freedom and more fun. We used to gather at the Park Inn Hotel where you could grill your own steak and have a glass of cheap red which suited our meagre earnings at the time. One day Mo, or Alan, as he was known then, asked me how I was handling the freelance gig. I said I found it hard to get motivated and was sleeping in and generally just hanging around. “Me too” he said, “I have to get in the car and drive around the block to pretend I’m going to work!” So we decided to rent an office together and found a place in Burton Street, Darlinghurst for fifty bucks a week plus 5 bucks we’d sling the film company receptionist downstairs to take messages while we were at lunch. You couldn’t miss lunch in those days. That’s where Mo introduced me to Judith, who, unfortunately can’t be here today, and we asked her look after our paltry finances. -

Australian Broadcasting Authority

Australian Broadcasting Authority annual report Sydney 2000 Annual Report 1999-2000 © Commonwealth of Australia 2000 ISSN 1320-2863 Design by Media and Public Relations Australian Broadcasting Authority Cover design by Cube Media Pty Ltd Front cover photo: Paul Thompson of DMG Radio, successful bidder for the new Sydney commercial radio licence, at the ABA auction in May 2000 (photo by Rhonda Thwaite) Printed in Australia by Printing Headquarters, NSW For inquiries about this report, contact: Publisher Australian Broadcasting Authority at address below For inquiries relating to freedom of information, contact: FOi Coordinator Australian Broadcasting Authority Level 15, 201 Sussex Street Sydney NSW 2000 Tel: (02) 9334 7700 Fax: (02) 9334 7799 .Postal address: PO Box Q500 Queen Victoria Building NSW 1230 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.aba.gov.au 2 AustJt"aHan Broadcasting Authority Level 1 S Darling Park 201 Sussex St Sydney POBoxQ500 Queen Victoria Building August 2000 NSW1230 Phone (02) 9334 7700 Fax (02) 9334 7799 Senator the Hon. RichardAlston E-mail [email protected] 'nister for Communications,Information Technology and the Arts DX 13012Marlret St Sydney liarnentHouse anberraACT 2600 In accordancewith the requirements of section 9 andSchedule 1 of the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997, I ampleased to present, on behalfof the Members of the AustralianBroadcasting Authority, thisannual reporton the operations of the llthorityfor the year 1999-2000. Annual Report 1999-2000 4 Contents Letter of transmittal 3 Members' report -

Women's Rights Or Wrongs?

Gough Whitlam Speaks on the Federal Referendums Great Court. 1pm. August 3rd Women's Rights or Wrongs? Inside... Usual Features Whitlam IF YOU'RE INVESTING IN A GREAT BODY Supports DO IT FEET FIRST Brooks For Women are specially designed to enhance a women's natural movement. Graduate Years of scientific research conducted by Michigan State University proved a women's wider hips, more flexible joints and different center of gravity require a shoe built especially for her. This research led to our exclusive design- Tax! the only design which fits a woman's body as well as her feet. We also add special Comfort Crafted features hke a patented built-in- slipper to hold your foot snugly and eliminate seams that cause blisters. Mrs Enid Whitlam, a Toowong pen sioner, has recently come out publically ATHLETIC SHOES DESIGNED FOR WOMEN ONLY. in support of the Federal governments proposed graduate tax on students. Mrs Wliitlam, a local identity and mud wres tling enthusiast said" All that most stu dents really needed was a damn good thrashing with a cricket bat to strengthen their character and 5 years compulsory military service." Mrs Whitlam believed that beating students about the head viciously with cricket bats was no PERSUASION REVELATION longer an option as bleeding heart, nancy-boy High mileage running shoe A 3/4 cut fitness shoe liberals had a stranglehold on the country. "In my with the Female Support System designed to give maximum view the graduate tax doesn't go far enough. My designed to accommodate cushioning and support to husband Gerald, always said that you only begin medial movement inherent in the female body. -

Ecaj Annual Report 5766 / 2006

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIAN JEWRY 2006/5766 Copyright 2006 Executive Council of Australian Jewry This report is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher. The publisher warrants that all due care and diligence has been taken in the research and presentation of material in this report. However readers must rely upon their own enquiries relating to any matter contained herein. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page Committee of Management and Councillors – 2005/2006 5 Presidents of the ECAJ: 1945-2006 7 A Tribute to Leslie Caplan 8 President’s Overview 10 ECAJ Photo Gallery 16 Executive Director’s Statement 22 Reports of Constituent Organisations 25 • Jewish Community Council of Victoria 25 • Jewish Community Council of Western Australian Inc 33 • Australian Capital Territory Jewish Community Inc 36 • Hobart Hebrew Congregation 40 • Queensland Jewish Board of Deputies 42 • New South Wales Jewish Board of Deputies 46 Reports of Affiliated and Observer Organisations 56 • Australian Federation of WIZO 56 • B'nai B'rith Australia/New Zealand 60 • Australasian Union of Jewish Students 64 • Union for Progressive Judaism 76 • National Council of Jewish Women of Australia 81 • Zionist Federation of Australia 86 • Maccabi Australia Inc 91 Reports of Consultants 93 • Report on Antisemitism in Australia – Jeremy Jones AM 93 • Australian Defence Force Report – Rabbi Raymond Apple AO 95 • Community Relations Report – Josie Lacey OAM 96 • Education Report – Peta Jones Pellach 101 • Masking our Differences: Purim in Cebu – Peta Jones Pellach 105 • & Jeremy Jones AM • World Jewish Congress Report – Grahame J. -

Censorship and the Political Cartoonist

Archived at the Flinders Academic Commons: http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/ This is the publisher’s copyrighted version of this article. The original can be found at: http://www.adelaide.edu.au/apsa/docs_papers/Others/Manning.pdf © 2004 APSA Published version of the paper reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or to reuse any copyrighted component of this work in other works must be obtained from APSA. Censorship and the Political Cartoonist Dr Haydon Manning School of Political and International Studies, Flinders University and Dr Robert Phiddian Department of English, Flinders University Refereed paper presented to the Australasian Political Studies Association Conference University of Adelaide 29 September – 1 October 2004 Manning & Phiddian: Censorship and the Political Cartoonist Abstract Cartoonist with the New Zealand Herald, Malcolm Evans, was dismissed from the paper after he refused to follow his editor’s instruction to cease cartooning on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Members of the Jewish community were upset by a number of his cartoons, drawn during the first half of 2003. As an award winning editorial cartoonist Evans, observed in his defense, that his cartoons may offend but that their content was not necessarily wrong.1 Much like his brethren cartoonists, he guards fiercely his licence to mock politicians, governments and states. This paper examines the space within which cartoonists examine political subjects, analyses the Evans case, assesses the legal environment and the parameter within which mass circulation newspaper editors operate. -

Migration of Mexicans to Australia

Migration of Mexicans to Australia MONICA LAURA VAZQUEZ MAGGIO Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences, University of New South Wales September 2013 Acknowledgements I would like to express my profound gratitude to a number of people who provided me with invaluable support throughout this entire PhD journey. I have been privileged to have two marvellous and supportive PhD supervisors. I am immensely grateful to my Social Sciences supervisor, Dr. Alan Morris, who guided me with his constant encouragement, valuable advice and enormous generosity. As a fresh new PhD student, full of excitement on my first days after I arrived in Australia, I remember encountering a recently graduated PhD student who, after I told her that my supervisor was Alan Morris, assured me I was in good hands. At that time, I had no idea of the magnitude of what she meant. Alan has truly gone above and beyond the role of a supervisor to guide me so brilliantly through this doctorate. He gracefully accepted the challenge of leading me in an entirely new discipline, as well as through the very challenging process of writing in a second language. Despite his vast commitments and enormous workload, Alan read my various manuscripts many times. I am also deeply thankful to my Economics supervisor, Dr. Peter Kriesler, for whom without his warm welcome, I would have not come to this country. I am extremely indebted to Peter for having put his trust in me before arriving in Australia and for giving me the opportunity to be part of this University.