THE MAG 17-07-05.Dtp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kells Bay Nursery

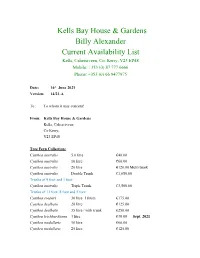

Kells Bay House & Gardens Billy Alexander Current Availability List Kells, Cahersiveen, Co. Kerry, V23 EP48 Mobile: +353 (0) 87 777 6666 Phone: +353 (0) 66 9477975 Date: 16th June 2021 Version: 14/21-A To : To whom it may concern! From: Kells Bay House & Gardens Kells, Caherciveen Co Kerry, V23 EP48 Tree Fern Collection: Cyathea australis 5.0 litre €40.00 Cyathea australis 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea australis 20 litre €120.00 Multi trunk Cyathea australis Double Trunk €1,650.00 Trunks of 9 foot and 1 foot Cyathea australis Triple Trunk €3,500.00 Trunks of 11 foot, 8 foot and 5 foot Cyathea cooperi 30 litre 180cm €175.00 Cyathea dealbata 20 litre €125.00 Cyathea dealbata 35 litre / with trunk €250.00 Cyathea leichhardtiana 3 litre €30.00 Sept. 2021 Cyathea medullaris 10 litre €60.00 Cyathea medullaris 25 litre €125.00 Cyathea medullaris 35 litre / 20-30cm trunk €225.00 Cyathea medullaris 45 litre / 50-60cm trunk €345.00 Cyathea tomentosisima 5 litre €50.00 Dicksonia antarctica 3.0 litre €12.50 Dicksonia antarctica 5.0 litre €22.00 These are home grown ferns naturalised in Kells Bay Gardens Dicksonia antarctica 35 litre €195.00 (very large ferns with emerging trunks and fantastic frond foliage) Dicksonia antarctica 20cm trunk €65.00 Dicksonia antarctica 30cm trunk €85.00 Dicksonia antarctica 60cm trunk €165.00 Dicksonia antarctica 90cm trunk €250.00 Dicksonia antarctica 120cm trunk €340.00 Dicksonia antarctica 150cm trunk €425.00 Dicksonia antarctica 180cm trunk €525.00 Dicksonia antarctica 210cm trunk €750.00 Dicksonia antarctica 240cm trunk €925.00 Dicksonia antarctica 300cm trunk €1,125.00 Dicksonia antarctica 360cm trunk €1,400.00 We have lots of multi trunks available, details available upon request. -

Post-Fire Dynamics of Cool Temperate Rainforest in the O'shannassy Catchment

Post-fire dynamics of Cool Temperate Rainforest in the O’Shannassy Catchment A. Tolsma, R. Hale, G. Sutter and M. Kohout July 2019 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 298 Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning PO Box 137 Heidelberg, Victoria 3084 Phone (03) 9450 8600 Website: www.ari.vic.gov.au Citation: Tolsma, A., Hale, R., Sutter, G. and Kohout, M. (2019). Post-fire dynamics of Cool Temperate Rainforest in the O’Shannassy Catchment. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research Technical Report Series No. 298. Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Heidelberg, Victoria. Front cover photo: Small stand of Cool Temperate Rainforest grading to Cool Temperate Mixed Forest with fire-killed Mountain Ash, O’Shannassy Catchment, East Central Highlands (Arn Tolsma). © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2019 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo, the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning logo and the Arthur Rylah Institute logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Printed by Melbourne Polytechnic Printroom ISSN 1835-3827 (Print) ISSN 1835-3835 (pdf/online/MS word) ISBN 978-1-76077-589-6 (Print) ISBN 978-1-76077-590-2 (pdf/online/MS word) Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. -

Growing Ferns Indoors

The British Pteridological Society For Fern Enthusiasts Further information is obtainable from: www.ebps.org.uk Copyright ©2016 British Pteridological Society Charity No. 1092399 Patron: HRH The Prince of Wales c/o Dept. of Life Sciences,The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD The British Pteridological Society For Fern Enthusiasts 125 th Anniversary 1891-2016 Phlebodium pseudoaureum in a living room Some further reading: Sub-tropical ferns in a modern conservatory Indoor ferns: caring for ferns. Boy Altman. (Rebo 1998) House Plants Loren Olsen. 2015. Gardening with Ferns Martin Rickard (David and Charles) From Timber Press: Fern Grower’s Manual Barbara Hoshizaki and Robbin Moran The Plant Lover’s Guide to Ferns Richie Stefan and Sue Olsen Growing Ferns Indoors The BPS would like to thank the Cambridge University Tropical epiphytic ferns in a heated greenhouse Botanical Gardens for their help with the indoor ferns RHS Chelsea Flower Show 2016 Growing Ferns Indoors Growing ferns in the home can be both relaxing and beneficial guard heaters to ward-off temperatures below 5C, although as the soft green foliage is pleasing to the eye and may also help many tender ferns fare better if the minimum winter Ferns that will grow in domestic living rooms, conservatories and in purifying air. It would appear that some ferns and their root- temperature is 10C. glasshouses can provide all-year interest and enjoyment. Some associated micro-organisms can biodegrade air and water ferns that will tolerate these environments are listed below but pollutants. Growing humid and tropical ferns there are many more to be found in specialist books on fern Glasshouses that have the sole purpose of growing plants offer culture. -

Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual

Table of Contents Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual 2015 Page 1 How to Use the Manual How to Use the Manual Please note that Waipa District Council has no controls over the way your electronic device prints the electronic version of the Manual and cannot guarantee that it will be consistent with the published version of the Manual. Version Control Version Date Updated By Section / Page # and Details 1.0 November 2012 Administrator Document approved by Council. 2.0 August 2013 Development Engineer Whole document updated to reflect OFI forms received. 2.1 September 2013 Development Engineer Whole document updated 2.2 August 2014 Development Engineer Whole document updated to reflect feedback from internal review. 2.3 December 2014 Development Engineer Whole document approved by Asset Managers 2.4 January 2015 Administrator Whole document renumbered and formatted. 2.5 May 2015 Administrator Document approved by Council. Page 2 Waipa District Development and Subdivision Manual 2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 3 Part 1: Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 Part 2: General Information ............................................................................................................ 7 Volume 1: Subdivision and Land Use Processes -

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886

The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 Sascha Nolden, Simon Nathan & Esme Mildenhall Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H November 2013 Published by the Geoscience Society of New Zealand Inc, 2013 Information on the Society and its publications is given at www.gsnz.org.nz © Copyright Simon Nathan & Sascha Nolden, 2013 Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H ISBN 978-1-877480-29-4 ISSN 2230-4495 (Online) ISSN 2230-4487 (Print) We gratefully acknowledge financial assistance from the Brian Mason Scientific and Technical Trust which has provided financial support for this project. This document is available as a PDF file that can be downloaded from the Geoscience Society website at: http://www.gsnz.org.nz/information/misc-series-i-49.html Bibliographic Reference Nolden, S.; Nathan, S.; Mildenhall, E. 2013: The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886. Geoscience Society of New Zealand miscellaneous publication 133H. 219 pages. The Correspondence of Julius Haast and Joseph Dalton Hooker, 1861-1886 CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Sumner Cave controversy Sources of the Haast-Hooker correspondence Transcription and presentation of the letters Acknowledgements References Calendar of Letters 8 Transcriptions of the Haast-Hooker letters 12 Appendix 1: Undated letter (fragment), ca 1867 208 Appendix 2: Obituary for Sir Julius von Haast 209 Appendix 3: Biographical register of names mentioned in the correspondence 213 Figures Figure 1: Photographs -

TAXON:Dicksonia Squarrosa (G. Forst.) Sw. SCORE

TAXON: Dicksonia squarrosa (G. SCORE: 18.0 RATING: High Risk Forst.) Sw. Taxon: Dicksonia squarrosa (G. Forst.) Sw. Family: Dicksoniaceae Common Name(s): harsh tree fern Synonym(s): Trichomanes squarrosum G. Forst. rough tree fern wheki Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 11 Sep 2019 WRA Score: 18.0 Designation: H(HPWRA) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Tree Fern, Invades Pastures, Dense Stands, Suckering, Wind-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 ? outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable to grazing animals y=1, n=-1 n 405 Toxic to animals y=1, n=0 n 406 Host for recognized pests and pathogens 407 Causes allergies or is otherwise toxic to humans 408 Creates a fire hazard in natural ecosystems y=1, n=0 y 409 Is a shade tolerant plant at some stage of its life cycle y=1, n=0 y Creation Date: 11 Sep 2019 (Dicksonia squarrosa (G. -

Full Article

NOTORNIS Journal of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand Volume 25 Part 4 December 1978 OFFICERS 1978 - 79 President - Mr. B. D. BELL, Wildlife Service, Dept. of Internal Affairs, Private Bag, Wellington Vice-president - Mr. M. L. FALCONER, 188 Miromiro Road, Normandale, Lower Hutt Editor - Mr. B. D. HEATHER, 10 Jocelyn Crescent, Silverstrearn Treasurer - Mr. H. W. M. HOGG, P.O. Box 3011, Dunedin Secretary - Mr. H, A. BEST, Wildlife Service, Dept. of Internal Affairs, Wellington Council Members: Dr. BEN D. BELL, 45 Gurney Road, Belmont, Lower Hutt Mrs. B. BROWN, 39 Red Hill Road, Papakura Dr. P. C. BULL, 131 Waterloo Road, Lower Hutt Mr D. E. CROCKETT, 21 McMillan Avenue, Kamo, Whangarei Mr. F. C. KINSKY, 338 The Parade, Island Bay, Wellington 5 Mrs. S. M. REED, 4 Mamaku Street, Auckland 5 Mr. R. R. SUTTON, Lorneville, No. 4 R.D., Invercargill Conveners and Organisers: Rare Birds Committee (Acting): Mr. B. D. BELL Beach Patrol: Mr. C. R. VEITCH, Wildlife Service, Dept. of Internal Affairs, P.O. Box 2220, Auckland Card Committee: Mr. R. N. THOMAS, 25 Ravenswood Drive, Forest Hill, Auckland 10 Field Investigation Committee: Mr. B. D. BELL ' Librarian: Miss A. J. GOODWIN, R.D. 1, Clevedon Nest Records: Mr. D. E. CROCKETT Recording (including material for Classified Surnmarised Notes) : Mr. R. B. SIBSON, 26 Entrican Avenue, Remuera, Auckland Representative on Member Bodies' Committee of Royal Society of N.Z.: Mr. B. D. BELL Assistant Editor: Mr A. BLACKBURN, 10 Score Road, Gisborne Editor of OSNZ News: Mr P. SAGAR, 2/362 Hereford St., Christchurch SUBSCRIPTIONS AND MEMBERSHIP Annual Subscription: Ordinary membership $6; Husband/Wife member- ship $9; Life membership $120 (age over 30); Junior member- ship (age under 20) $4.50; Family membership (one Notornis er household) other members of a family living in one house iold where one is already a member $3; Institutional subscrip tions $10; overseas subscriptions $2.00 extra. -

A Synthesis of Geophysical and Biological Assessment to Determine Restoration Priorities

How can geomorphology inform ecological restoration? A synthesis of geophysical and biological assessment to determine restoration priorities A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Physical Geography By Leicester Cooper School of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences Victoria University Wellington 2012 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Acknowledgements Many thanks and much appreciation go to my supervisors Dr Bethanna Jackson and Dr Paul Blaschke, whose sage advice improved this study. Thanks for stepping into the breach; I hope you didn’t regret it. Thanks to the Scholarships Office for the Victoria Master’s (by thesis) Scholarship Support award which has made the progression of the study much less stressful. Thanks go to the various agencies that have provided assistance including; Stefan Ziajia from Kapiti Coast District Council, Nick Page from Greater Wellington Regional Council, Eric Stone from Department of Conservation, Kapiti office. Appreciation and thanks go to Will van Cruchten, for stoically putting up with my frequent calls requesting access to Whareroa Farm. Also, many thanks to Prof. Shirley Pledger for advice and guidance in relation to the statistical methods and analysis without whom I might still be working on the study. Any and all mistakes contained within I claim sole ownership of. Thanks to the generous technicians in the Geography department, Andrew Rae and Hamish McKoy and fellow students, including William Ries, for assistance with procurement of aerial images and Katrin Sattler for advice in image processing. To Dr Murray Williams, without whose sudden burst at one undergraduate lecture I would not have strayed down the path of ecological restoration. -

The Lower Cretaceous Flora of the Gates Formation from Western Canada

The Lower Cretaceous Flora of the Gates Formation from Western Canada A Shesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Geological Sciences Univ. of Saska., Saskatoon?SI(, Canada S7N 3E2 b~ Zhihui Wan @ Copyright Zhihui Mian, 1996. Al1 rights reserved. National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON KlA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libraxy of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur foxmat électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. College of Graduate Studies and Research SUMMARY OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirernents for the DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ZHIRUI WAN Depart ment of Geological Sciences University of Saskatchewan Examining Commit tee: Dr. -

1999 New Zealand Botanical Society

NEW ZEALAND BOTANICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER NUMBER 57 SEPTEMBER 1999 New Zealand Botanical Society President: Jessica Beever Secretary/Treasurer: Anthony Wright Committee: Bruce Clarkson, Colin Webb, Carol West Address: c/- Canterbury Museum Rolleston Avenue CHRISTCHURCH 8001 NEW ZEALAND Subscriptions The I999 ordinary and institutional subs are $18 (reduced to $15 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). The 1999 student sub, available to full-time students, is $9 (reduced to $7 if paid by the due date on the subscription invoice). Back issues of the Newsletter are available at $2.50 each from Number 1 (August 1985) to Number 46 (December 1996), $3.00 each from Number 47 (March 1997) to Number 50 (December 1997), and $3.75 each from Number 51 (March 1998) onwards. Since 1986 the Newsletter has appeared quarterly in March, June, September and December. New subscriptions are always welcome and these, together with back issue orders, should be sent to the Secretary/Treasurer (address above). Subscriptions are due by 28 February of each year for that calendar year. Existing subscribers are sent an invoice with the December Newsletter for the next year's subscription which offers a reduction if this is paid by the due date. If you are in arrears with your subscription a reminder notice comes attached to each issue of the Newsletter. Deadline for next issue The deadline for the December 1999 issue (Number 58) is 26 November 1999. Please forward contributions to: Dr Carol J. West, c/- Department of Conservation PO Box 743 Invercargill Contributions may be provided on an IBM compatible floppy disc (Word) or by e-mail to [email protected] Cover Illustration Plagiochila ramosissima with antheridial branches. -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 127, 1993 23

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 127, 1993 23 RAINFOREST IN EASTERN TASMANIA - FLORISTICS AND CONSERVATION by M.G. Neyland and M.J. Brown (with two tables, four text-figures and one appendix) NEYLAND, M. G. & BROWN, M. J., 1993 (31:viii): Rainforest in eastern Tasmania - floristics and conservation. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 127: 23-32. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.127.23 ISSN 0080-4703. Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Environment and Land Management, GPO Box 44A, Hobart, Tasmania 7001 (MGN); Forestry Commission, Macquarie Street, Hobart, Tasmania 7000 (MJB). Six floristic communities are described from rainforest in northern and eastern Tasmania. The communities occur in lower rainfall areas, where they are often restricted ro fire-protected sites. They have climatic envelopes which are significantly distinct from each other and from rainforest in higher rainfall areas. The conservation status of the communities is assessed. Key Words: rainforest, Tasmania, conservation, relicts. INTRODUCTION METHODS Temperate rainforests worldwide are restricted mainly to the TASFORHAB profiles (Peters 1984) were collected from coastal and maritime zones, and generally occur in areas of relict rainforest patches throughout the study area. These high rainfall (Kellogg 1992). All the rainforests of Tasmania profiles record the floristics, species abundance and the are relicts of extensive rainforest which once occurred on the structure of the forest. A number of profiles already on the ancient continent Gondwana (Hill 1990, Nelson 1981). TASFORHAB data base were used to cross-check results, Many of the genera which are characteristic of rainforest in and to locate potential rainforest sites. -

Downloadable PDF Format On

Checklist of the New Zealand Flora Ferns and Lycophytes 2019 A New Zealand Plant Names Database Report © Landcare Research New Zealand Limited 2019 This copyright work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. Attribution if redistributing to the public without adaptation: "Source: Landcare Research" Attribution if making an adaptation or derivative work: "Sourced from Landcare Research" DOI: 10.26065/6s30-ex64 CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Checklist of the New Zealand flora : ferns and lycophytes [electronic resource] / Allan Herbarium. – [Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand] : Landcare Research Manaaki Whenua, 2017- . Online resource Annual August 2017- ISSN 2537-9054 I.Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd. II. Allan Herbarium. Citation and Authorship Schönberger, I.; Wilton, A.D.; Brownsey, P.J.; Perrie, L.R.; Boardman, K.F.; Breitwieser, I.; de Pauw, B.; Ford, K.A.; Gibb, E.S.; Glenny, D.S.; Korver, M.A.; Novis, P.M.; Prebble, J.M.; Redmond, D.N.; Smissen, R.D.; Tawiri, K. (2019) Checklist of the New Zealand Flora – Ferns and Lycophytes. Lincoln, Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research. http://dx.doi.org/10.26065/6s30-ex64 This report is generated using an automated system and is therefore authored by the staff at the Allan Herbarium and collaborators who currently contribute directly to the development and maintenance of the New Zealand Plant Names Database (PND). Authors are listed alphabetically after the fourth author. Authors have contributed as follows: Leadership: Wilton, Breitwieser Database editors: Wilton, Schönberger, Gibb Taxonomic and nomenclature research and review for the PND: Schönberger, Wilton, Gibb, Breitwieser, Brownsey, de Lange, Ford, Fife, Glenny, Novis, Perrie, Prebble, Redmond, Smissen Information System development: Wilton, De Pauw, Cochrane Technical support: Boardman, Korver, Redmond, Tawiri Contents Introduction.......................................................................................................................................................