The Architecture of Control: Shaker Dwelling Houses and the Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of a Shaker Bible

Inspiration, Revelation, and Scripture: The Story of a Shaker Bible STEPHEN J. STEIN OR MORE than two hundred years the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, a religious commu- Fnity commonly known as the Shakers, has been involved with publishing. In 1790 'the first printed statement of Shaker theology' appeared anonymously in Bennington, Vermont, under the imprint of 'Haswell & Russell." Entitied A Concise Statement of the Principles of the Only True Church, according to the Gospel of the Present Appearance of Christ, this publication marked a departure from the pattern established by the founder, Ann Lee, an Englishwoman who came to America in 1774. Lee, herself illiter- ate, feared fixed statements of behef, and forbade her followers to write such documents. Within the space of two decades, however, the Shakers rejected Lee's counsel and turned with increasing fre- quency to the printing press in order to defend themselves against Earlier versions of this essay were presented at the Museum of Our National Heritage, Lexington, Massachusetts (1993), at the annual meeting of the American Society of Church History in San Erancisco (1994), and at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio (1995), under the auspices of the Arthur C. Wickenden Memorial Lectureship. My special thanlcs to Jerry Grant, who shared some of his research notes dealing with the Sacred Roll, which I have used in this version of the essay. I. See Mary L. Richmond, Shaker Literature: A Bibliography (2 vols., Hancock, Mass.: Shaker Community, Inc., 1977), i: 145-46. Richmond echoes the common judgment con- cerning the authorship of this tract, attributing it to Joseph Meacham, an early American convert to Shakerism. -

Me0330data.Pdf

SABBATHDAY LAKE SHAKER VILLAGE HABS ME-227 State Route 26, two miles south of the junction with State Route 122 HABS ME-227 New Gloucester vicinity Cumberland County Maine PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY SABBATHDAY LAKE SHAKER VILLAGE HABS No. ME-227 Location: State Route 26, two miles south of the junction with State Route 122 New Gloucester vicinity, Cumberland County, Maine The village is located on the east and west sides of State Route 26 Note: For shelving purposes at the Library of Congress, Cumberland County was selected as the main location for Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village. A portion of the village is also located in Androscoggin County. USGS Gray, Mechanic Falls, Minot, Raymond, Maine Quadrangles Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates (NAD83): NW 38711.37 4874057.31 NE 393479.37 487057.18 SE 393477.82 4868742.10 SW 387411.86 486742.35 Present Owner: The Shaker Society (The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing) Present Occupant: Members of the Shaker Society Present Use: Communal Shaker working village and museum Significance: This is the world’s only remaining active Shaker village community that reflects the evolution of Shaker religion and architecture from the late eighteenth century to the present. SABBATHDAY LAKE SHAKER VILLAGE HABS No. ME-227 (Page 2) PART I: HISTORICAL INFORMATION A. HISTORICAL CONTEXT 1. Historical Development: The United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing at Sabbathday Lake, Maine is the world's only remaining active Shaker community. -

Early Mormon and Shaker Visions of Sanctified Community

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 44 Issue 1 Article 4 1-1-2005 Early Mormon and Shaker Visions of Sanctified Community J. Spencer Fluhman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Fluhman, J. Spencer (2005) "Early Mormon and Shaker Visions of Sanctified Community," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 44 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol44/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fluhman: Early Mormon and Shaker Visions of Sanctified Community Early Mormon and Shaker Visions of Sanctified Community /. Spencer Fluhman olly Knight's health was failing as she and her family trudged toward Pwestern Missouri. Having accepted Joseph Smith Jr. as God's prophet on earth, the Knights left their Colesville, New York, farm and joined with other Mormon converts at Kirtland, Ohio, in 1831. Finding a brief respite there, they again set out, this time for the city of "Zion" that Joseph Smith said they would help build in Jackson County, Missouri. Worried that Polly was too ill to complete the trek, her family considered stopping in hopes she might recover. But "she would not consent to stop traveling," recalled her son Newell: "Her only, or her greatest desire was to set her feet upon the land of Zion, and to have her body interred in that land." Fearing the worst, Newell bought lumber for a coffin in case she expired en route. -

VALID BAPTISM Advisory List Prepared by the Worship Office and the Metropolitan Tribunal for the Archdiocese of Detroit

249 VALID BAPTISM Advisory list prepared by the Worship Office and the Metropolitan Tribunal for the Archdiocese of Detroit African Methodist Episcopal Patriotic Chinese Catholics Amish Polish National Church Anglican (valid Confirmation too) Ancient Eastern Churches Presbyterians (Syrian-Antiochian, Coptic, Reformed Church Malabar-Syrian, Armenian, Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Ethiopian) Day Saints (since 2001 known as the Assembly of God Community of Christ) Baptists Society of Pius X Christian and Missionary Alliance (followers of Bishop Marcel Lefebvre) Church of Christ United Church of Canada Church of God United Church of Christ Church of the Brethren United Reformed Church of the Nazarene Uniting Church of Australia Congregational Church Waldesian Disciples of Christ Zion Eastern Orthodox Churches Episcopalians – Anglicans LOCAL DETROIT AREA COMMUNITIES Evangelical Abundant Word of Life Evangelical United Brethren Brightmoor Church Jansenists Detroit World Outreach Liberal Catholic Church Grace Chapel, Oakland Lutherans Kensington Community Methodists Mercy Rd. Church, Redford (Baptist) Metropolitan Community Church New Life Ministries, St. Clair Shores Old Catholic Church Northridge Church, Plymouth Old Roman Catholic Church DOUBTFUL BAPTISM….NEED TO INVESTIGATE EACH Adventists Moravian Lighthouse Worship Center Pentecostal Mennonite Seventh Day Adventists DO NOT CELEBRATE BAPTISM OR HAVE INVALID BAPTISM Amana Church Society National David Spiritual American Ethical Union Temple of Christ Church Union Apostolic -

Handbook of Religious Beliefs and Practices

STATE OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES 1987 FIRST REVISION 1995 SECOND REVISION 2004 THIRD REVISION 2011 FOURTH REVISION 2012 FIFTH REVISION 2013 HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES INTRODUCTION The Department of Corrections acknowledges the inherent and constitutionally protected rights of incarcerated offenders to believe, express and exercise the religion of their choice. It is our intention that religious programs will promote positive values and moral practices to foster healthy relationships, especially within the families of those under our jurisdiction and within the communities to which they are returning. As a Department, we commit to providing religious as well as cultural opportunities for offenders within available resources, while maintaining facility security, safety, health and orderly operations. The Department will not endorse any religious faith or cultural group, but we will ensure that religious programming is consistent with the provisions of federal and state statutes, and will work hard with the Religious, Cultural and Faith Communities to ensure that the needs of the incarcerated community are fairly met. This desk manual has been prepared for use by chaplains, administrators and other staff of the Washington State Department of Corrections. It is not meant to be an exhaustive study of all religions. It does provide a brief background of most religions having participants housed in Washington prisons. This manual is intended to provide general guidelines, and define practice and procedure for Washington State Department of Corrections institutions. It is intended to be used in conjunction with Department policy. While it does not confer theological expertise, it will, provide correctional workers with the information necessary to respond too many of the religious concerns commonly encountered. -

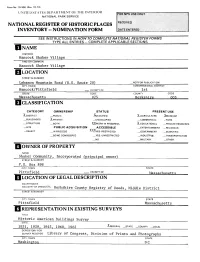

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ INAME HISTORIC Hancock Shaker Village__________________________________ AND/ORCOMMON Hancock Shaker Village STREET & NUMBER Lebanon Mountain Road ("U.S. Route 201 —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Hancock/Pittsfield _. VICINITY OF 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Berkshire 003 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT _PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED X_AGRICULTURE -XMUSEUM __BUILDING(S) X.RRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE __BOTH XXWORK IN PROGRESS ^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS XXXYES . RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Shaker Community, Incorporated fprincipal owner) STREET& NUMBER P.O. Box 898 CITY. TOWN STATE Pittsfield VICINITY OF Mas s achus e 1.1. LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEoaETc. Berkshire County Registry of Deeds, Middle District STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Pittsfield Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1931, 1959, 1945, 1960, 1962 ^FEDERAL _STATE _COUNTY ._LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY, TOWN STATE Washington DC DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X_EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED .^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XXALTERED - restored —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Hancock Shaker Village is located on a 1,000-acre tract of land extending north and south of Lebanon Mountain Road (U.S. -

PILLS. Certain of the De- RADWATS PILLS Dta for He Left a Very Fortunu to His Fire Sons, Deer of Divorce, from Ber Haiband, the DR

& MKDICIXES. MERCHANDISE, &u. Productloa of Beetroot Sujrnr lions of Minister and those of Deputy will MEKCtlANDlSE, &0. SUGA1! & MOLASSES. LEGAL NOTICES. In CierBiuay. establish between the Chamber and my Government; the presence of all the Min- X880 H&-waii- an SOMETHING WORTH READING! isters in the Chamber ; the deliberation in Itiao Suprome Court of the I "When at Cologne, we were told that the Council of affairs ; a un- R,K SLB 33L Air. State sincere JUST RECEIVED Islands. the late Joest had th merit of derstanding with will consti- the Erst minafictory for the the majority, EX tute for the country all the guarantees Kuhllanl. ts. Usury O. Tarks Divorce. re&ninar of foreign sorars, and afterwards v fn. which we seek iu our common solicitude. CompIniBMBt CASTLE & COOKE for the extraction of ssgar from tho bcot- - 1869 W1IK11B.VS, the la I have already proved several times how 2L Wood, entitled cause, bas filed a u W. root, anu reamng uie suptr uuuian. disposed I was." for tho public interest, to petition unto the Honorable A. S. llartwell, ARE business had proved so lucrative that l"he renounce my prerogatives. FROM BREMEN, Jnitlce of tho Supreme Court, praying for a PILLS. certain of The De- RADWATS PILLS Dta For he left a very fortunu to his fire sons, deer of divorce, from ber haiband, the DR. hrp modifications which have decided to pro- A Large Merchan- Stocaacb, Bowels, and 3"oxj3t which them individually several I and Varied Assortment of fendant aforesaid, on the grounds of willful EKiMif the Littr. -

The Origins of Millerite Separatism

The Origins of Millerite Separatism By Andrew Taylor (BA in History, Aurora University and MA in History, University of Rhode Island) CHAPTER 1 HISTORIANS AND MILLERITE SEPARATISM ===================================== Early in 1841, Truman Hendryx moved to Bradford, Pennsylvania, where he quickly grew alienated from his local church. Upon settling down in his new home, Hendryx attended several services in his new community’s Baptist church. After only a handful of visits, though, he became convinced that the church did not believe in what he referred to as “Bible religion.” Its “impiety” led him to lament, “I sometimes almost feel to use the language [of] the Prophecy ‘Lord, they have killed thy prophets and digged [sic] down thine [sic] altars and I only am left alone and they seek my life.”’1 His opposition to the church left him isolated in his community, but his fear of “degeneracy in the churches and ministers” was greater than his loneliness. Self-righteously believing that his beliefs were the “Bible truth,” he resolved to remain apart from the Baptist church rather than attend and be corrupted by its “sinful” influence.2 The “sinful” church from which Hendryx separated himself was characteristic of mainstream antebellum evangelicalism. The tumultuous first decades of the nineteenth century had transformed the theological and institutional foundations of mainstream American Protestantism. During the colonial era, American Protestantism had been dominated by the Congregational, Presbyterian, and Anglican churches, which, for the most part, had remained committed to the theology of John Calvin. In Calvinism, God was envisioned as all-powerful, having predetermined both the course of history and the eternal destiny of all humans. -

Trustee's Building, Canterbury Shaker Village

NEW HAMPSHIRE DIVISION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES State of New Hampshire, Department of Cultural Resources 603-271-3483 19 Pillsbury Street, 2 nd floor, Concord NH 03301-3570 603-271-3558 Voice/ TDD ACCESS: RELAY NH 1-800-735-2964 FAX 603-271-3433 http://www.nh.gov/nhdhr [email protected] REPORT ON THE TRUSTEES’ BUILDING CANTERBURY SHAKER VILLAGE CANTERBURY, NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES L. GARVIN 18 NOVEMBER 2001 Summary: The Trustees’ Building or office of the Church Family at Canterbury Shaker Village was the chief point of contact and commerce between the Church Family and the World. The building was the first and only brick structure built by the Church Family, and was constructed of materials of exceptional quality and workmanship. Built with fine bricks that were manufactured by the Shakers, the Trustees’ Building reveals much about the Shakers’ skill as brickmakers and as masons. The Trustees’ Building is a structure of statewide significance in the history of masonry construction in New Hampshire. Although built between 1830 and 1832, when the federal style was quickly waning and giving way to the Greek Revival in neighboring communities, the Trustees’ Building is stylistically conservative. Its interior detailing reflects the federal style, as modified and refined by the Shakers, more fully than any other structure at the village and perhaps more fully than any other Shaker building in New Hampshire. The structure therefore possesses stylistic significance as a document of the Shakers’ adoption and modification of an architectural style that was prevalent in the World. The building’s significance in technology, workmanship, and style would make the structure individually eligible for the National Register of Historic Places if it were evaluated alone. -

Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection, 1771-1933 FM.MS.S

• THE TRUSTEES OF RESERVATIONS ARCHIVES & RESEARCH CENTER Guide to Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection, 1771-1933 FM.MS.S.Coll.1 by Anne Mansella & Sarah Hayes August 2018 The processing of this collection was funded in part by Mass Humanities, which receives support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and is an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Archives & Research Center 27 Everett Street, Sharon, MA 02067 www.thetrustees.org [email protected] 781-784-8200 The Trustees of Reservations – www.thetrustees.org Date Contents Box Folder/Item No. Extent: 15 boxes (includes 2 oversize boxes) Linear feet: 15 Copyright © 2018 The Trustees of Reservations ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION PROVENANCE Manuscript materials were first acquired by Clara Endicott Sears beginning in 1918 for her Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Massachusetts. Materials continued to be collected by the museum throughout the 20th century. In 2016, Fruitlands Museum became The Trustees’ 116th reservation, and the Shaker manuscript materials were relocated to the Archives & Research Center in Sharon, Massachusetts. In Harvard, the Fruitlands Museum site continues to display the objects that Sears collected. The museum features three separate collections of significant Shaker, Native American, and American art and artifacts, as well as a historic farmhouse that was once home to the family of Louisa May Alcott and is recognized as a National Historic Landmark. OWNERSHIP & LITERARY RIGHTS The Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection is the physical property of The Trustees of Reservations. Literary rights, including copyright, belong to the authors or their legal heirs and assigns. RESTRICTIONS ON ACCESS This collection is open for research. Some items may be restricted due to handling condition of materials. -

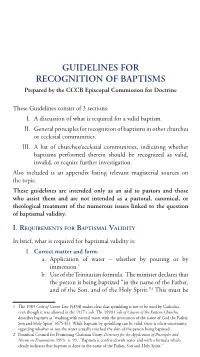

Guidelines for Recognition of Baptisms

First Church of Christ, Scientist Unitarian Universalist I (Mary Baker Eddy) - no baptism I Unitarians I Foursquare Gospel Church V United Church of Christ V General Assembly of Spiritualists I United Church of Canada V Hephzibah Faith Missionary Association I United Reformed V House of David Church I United Society of Believers I Iglesia ni Kristo (Phillippines) I Uniting Church in Australia V GUIDELINES FOR Independent Church of Filipino Christians I Universal Emancipation Church I RECOGNITION OF BAPTISMS Jehovah’s Witnesses (Watchtower Society) I Waldensian V Liberal Catholic Church V Worldwide Church of God (invalid before mid-1990’s) I Prepared by the CCCB Episcopal Commission for Doctrine Lutheran V Zion V Masons / Freemasons - no baptism I These Guidelines consist of 3 sections: Mennonite Churches ? I. A discussion of what is required for a valid baptism. APPENDIX: SOME MAGISTERIAL SOURCES TO BE CONSULTED Methodist V II. General principles for recognition of baptisms in other churches Metropolitan Community Church ? 1983 Code of Canon Law, n. 849-878. or ecclesial communities. Moonies (Reunification Church) I 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, n. 672-691. III. A list of churches/ecclesial communities, indicating whether Moravian Church ? Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity,Directory for the baptisms performed therein should be recognized as valid, National David Spiritual Temple of Christ Church Union I Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism, 1993, n. 92-101. invalid, or require further investigation. National Spiritualist Association I Catechism of the Catholic Church, n. 1213-1284. Also included is an appendix listing relevant magisterial sources on The New Church I the topic. -

Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God

American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 9 Number 1 Pages 3-39 January 2015 Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God Stephen J. Paterwic Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq Part of the American Studies Commons This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. Paterwic: Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God By Stephen J. Paterwic A review of: Shaker Autobiographies, Biographies and Testimonies, 1806-1907, edited by Glendyne R. Wergland and Christian Goodwillie. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2014. 3 volume set. Let the Shakers Speak for Themselves In 1824 teenager Mary Antoinette Doolittle felt drawn to the Shakers and sought every opportunity to obtain information about them. By chance, while visiting her grandmother, she encountered two young women who had just left the New Lebanon community. “Mary” was thrilled with the opportunity to hear them tell their story.1 Suddenly “something like a voice” said to her, “Why listen to them? Go to the Shakers, visit, see and learn for yourself who and what they are!”2 This idea is echoed in the testimony of Thomas Stebbins of Enfield, Connecticut, who was not satisfied to hear about the Shakers. “But I had a feeling to go and see them, and judge for myself.” (1:400) Almost two hundred years later, this is still the best advice for people seeking to learn about the Shakers.