Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection, 1771-1933 FM.MS.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Me0330data.Pdf

SABBATHDAY LAKE SHAKER VILLAGE HABS ME-227 State Route 26, two miles south of the junction with State Route 122 HABS ME-227 New Gloucester vicinity Cumberland County Maine PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY SABBATHDAY LAKE SHAKER VILLAGE HABS No. ME-227 Location: State Route 26, two miles south of the junction with State Route 122 New Gloucester vicinity, Cumberland County, Maine The village is located on the east and west sides of State Route 26 Note: For shelving purposes at the Library of Congress, Cumberland County was selected as the main location for Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village. A portion of the village is also located in Androscoggin County. USGS Gray, Mechanic Falls, Minot, Raymond, Maine Quadrangles Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates (NAD83): NW 38711.37 4874057.31 NE 393479.37 487057.18 SE 393477.82 4868742.10 SW 387411.86 486742.35 Present Owner: The Shaker Society (The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing) Present Occupant: Members of the Shaker Society Present Use: Communal Shaker working village and museum Significance: This is the world’s only remaining active Shaker village community that reflects the evolution of Shaker religion and architecture from the late eighteenth century to the present. SABBATHDAY LAKE SHAKER VILLAGE HABS No. ME-227 (Page 2) PART I: HISTORICAL INFORMATION A. HISTORICAL CONTEXT 1. Historical Development: The United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing at Sabbathday Lake, Maine is the world's only remaining active Shaker community. -

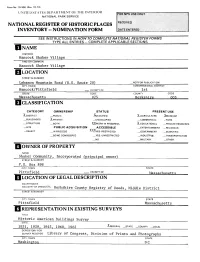

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ INAME HISTORIC Hancock Shaker Village__________________________________ AND/ORCOMMON Hancock Shaker Village STREET & NUMBER Lebanon Mountain Road ("U.S. Route 201 —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Hancock/Pittsfield _. VICINITY OF 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Berkshire 003 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT _PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED X_AGRICULTURE -XMUSEUM __BUILDING(S) X.RRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE __BOTH XXWORK IN PROGRESS ^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS XXXYES . RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Shaker Community, Incorporated fprincipal owner) STREET& NUMBER P.O. Box 898 CITY. TOWN STATE Pittsfield VICINITY OF Mas s achus e 1.1. LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEoaETc. Berkshire County Registry of Deeds, Middle District STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Pittsfield Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1931, 1959, 1945, 1960, 1962 ^FEDERAL _STATE _COUNTY ._LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY, TOWN STATE Washington DC DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X_EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED .^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XXALTERED - restored —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Hancock Shaker Village is located on a 1,000-acre tract of land extending north and south of Lebanon Mountain Road (U.S. -

Common Labor, Common Lives: the Social Construction of Work in Four Communal Societies, 1774-1932 Peter Andrew Hoehnle Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2003 Common labor, common lives: the social construction of work in four communal societies, 1774-1932 Peter Andrew Hoehnle Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hoehnle, Peter Andrew, "Common labor, common lives: the social construction of work in four communal societies, 1774-1932 " (2003). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 719. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/719 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Common labor, common lives: The social construction of work in four communal societies, 1774-1932 by Peter Andrew Hoehnle A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Agricultural History and Rural Studies Program of Study Committee: Dorothy Schwieder, Major Professor Pamela Riney-Kehrberg Christopher M. Curtis Andrejs Plakans Michael Whiteford Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2003 © Copyright Peter Andrew Hoehnle, 2003. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3118233 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Trustee's Building, Canterbury Shaker Village

NEW HAMPSHIRE DIVISION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES State of New Hampshire, Department of Cultural Resources 603-271-3483 19 Pillsbury Street, 2 nd floor, Concord NH 03301-3570 603-271-3558 Voice/ TDD ACCESS: RELAY NH 1-800-735-2964 FAX 603-271-3433 http://www.nh.gov/nhdhr [email protected] REPORT ON THE TRUSTEES’ BUILDING CANTERBURY SHAKER VILLAGE CANTERBURY, NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES L. GARVIN 18 NOVEMBER 2001 Summary: The Trustees’ Building or office of the Church Family at Canterbury Shaker Village was the chief point of contact and commerce between the Church Family and the World. The building was the first and only brick structure built by the Church Family, and was constructed of materials of exceptional quality and workmanship. Built with fine bricks that were manufactured by the Shakers, the Trustees’ Building reveals much about the Shakers’ skill as brickmakers and as masons. The Trustees’ Building is a structure of statewide significance in the history of masonry construction in New Hampshire. Although built between 1830 and 1832, when the federal style was quickly waning and giving way to the Greek Revival in neighboring communities, the Trustees’ Building is stylistically conservative. Its interior detailing reflects the federal style, as modified and refined by the Shakers, more fully than any other structure at the village and perhaps more fully than any other Shaker building in New Hampshire. The structure therefore possesses stylistic significance as a document of the Shakers’ adoption and modification of an architectural style that was prevalent in the World. The building’s significance in technology, workmanship, and style would make the structure individually eligible for the National Register of Historic Places if it were evaluated alone. -

Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God

American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 9 Number 1 Pages 3-39 January 2015 Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God Stephen J. Paterwic Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq Part of the American Studies Commons This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. Paterwic: Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God By Stephen J. Paterwic A review of: Shaker Autobiographies, Biographies and Testimonies, 1806-1907, edited by Glendyne R. Wergland and Christian Goodwillie. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2014. 3 volume set. Let the Shakers Speak for Themselves In 1824 teenager Mary Antoinette Doolittle felt drawn to the Shakers and sought every opportunity to obtain information about them. By chance, while visiting her grandmother, she encountered two young women who had just left the New Lebanon community. “Mary” was thrilled with the opportunity to hear them tell their story.1 Suddenly “something like a voice” said to her, “Why listen to them? Go to the Shakers, visit, see and learn for yourself who and what they are!”2 This idea is echoed in the testimony of Thomas Stebbins of Enfield, Connecticut, who was not satisfied to hear about the Shakers. “But I had a feeling to go and see them, and judge for myself.” (1:400) Almost two hundred years later, this is still the best advice for people seeking to learn about the Shakers. -

Preparation for a Group Trip to Hancock Shaker Village Before Your Visit Lay a Foundation So That the Youngs

Preparation for a Group Trip to Hancock Shaker Village Before your visit Lay a foundation so that the youngsters know why they are going on this trip. Talk about things for the students to look for and questions that you hope to answer at the Village. Remember that the outdoor experiences at the Village can be as memorable an indoor ones. Information to help you is included in this package, and more is available online at www.hancockshakervillage.org. Plan to divide into small groups, and decide if specific focus topics will be assigned. Perhaps a treasure hunt for things related to a focus topic can make the experience more meaningful. Please review general museum etiquette with your class BEFORE your visit and ON the bus: • Please organize your class into small groups of 510 students per adult chaperone. • Students must stay with their chaperones at all times, and chaperones must stay with their assigned groups. • Please walk when inside buildings and use “inside voices.” • Listen respectfully when an interpreter is speaking. • Be respectful and courteous to other visitors. • Food or beverages are not allowed in the historic buildings. • No flash photography is allowed inside the historic buildings. • Be ready to take advantage of a variety of handson and mindson experiences! Arrival Procedure A staff member will greet your group at the designated Drop Off and Pick Up area – clearly marked by signs on our entry driveway and located adjacent to the parking lot and the Visitor Center. We will escort your group to the Picnic Area, which has rest rooms and both indoor and outdoor picnic tables. -

Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith

American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 5 Number 3 Pages 11-137 July 2011 Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith Galen Beale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq Part of the American Studies Commons This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. Beale: Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith By Galen Beale And as she turned and looked at an apple tree in full bloom, she exclaimed: — How beautiful this tree looks now! But some of the apples will soon fall off; some will hold on longer; some will hold on till they are half grown and will then fall off; and some will get ripe. So it is with souls that set out in the way of God. Many set out very fair and soon fall away; some will go further, and then fall off, some will go still further and then fall; and some will go through.1 New England was a hotbed of discontent in the second half of the eighteenth century. Both civil and religious events stirred its citizenry to action. Europeans wished to govern this new, resource-rich country, causing continual fighting, and new religions were springing up in reaction to the times. The French and Indian War had aligned the British with the colonists, but that alliance soon dissolved as the British tried to extract from its colonists the cost of protecting them. -

NBMAA Anything but Simple Press Release

The New Britain Museum of American Art Presents Anything but Simple: Shaker Gift Drawings and the Women Who Made Them August 6, 2020-January 10, 2021 NEW BRITAIN, CONN., August 3, 2020, As a part of the 2020/20+ Women @ NBMAA initiative, The New Britain Museum of American Art (NBMAA) is thrilled to present Anything but Simple: Shaker Gift Drawings and the Women Who Made Them, August 6, 2020 through January 10, 2021. Organized by Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield, MA, Anything but Simple features rare Shaker “gift” or “spirit” drawings created by Shaker women in the mid-1800s, a period known as the Era of Manifestations. During that time, members of Shaker society created dances, songs, and drawings inspired by spiritual revelations or supernatural “gifts.” Colorful, decorative, and complex, “gift” drawings expressed messages of love, dedication to Shaker belief, and the promise of heaven following the earthly journey. Anything but Simple presents 25 of the 200 gift drawings extant in public and private collections today. This group of drawings, made between 1843 and 1857, is widely considered one of the world’s finest collections and includes the most famous gift drawing in existence: Hannah Cohoon’s 1854 Tree of Life. The Shaker Soul The drawings were made by young Shaker women dubbed “instruments” by their elders due to the fact that the women claimed they received these images as gifts from the spirit world. It is perhaps not surprising that a religion founded by a woman should find significant spiritual messages coming from women, even a century before women won the right to vote in the United States. -

288 Shaker Road City/Town: Canterbury State: NH County

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CANTERBURY SHAKER VILLAGE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: CANTERBURY SHAKER VILLAGE Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 288 Shaker Road Not for publication: N/a City/Town: Canterbury Vicinity: N/A State: NH County: Merrimack Code 013 Zip Code: 03224 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private; X Building(s) :__ Public-local:__ District; X Public-State:__ Site:__ Public-Federal: Structure:__ Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing _24 Q buildings 0 sites 0 structures 0 objects 28 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 28 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CANTERBURY SHAKER VILLAGE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

The Church Family Orchard of the Watervliet Shaker Community

The Church Family Orchard of the Watervliet Shaker Community Elizabeth Shaver Illustrations by Elizabeth Lee PUBLISHED BY THE SHAKER HERITAGE SOCIETY 25 MEETING HOUSE ROAD ALBANY, N. Y. 12211 www.shakerheritage.org MARCH, 1986 UPDATED APRIL, 2020 A is For Apple 3 Preface to 2020 Edition Just south of the Albany International called Watervliet, in 1776. Having fled Airport, Heritage Lane bends as it turns from persecution for their religious beliefs from Ann Lee Pond and continues past an and practices, the small group in Albany old cemetery. Between the pond and the established the first of what would cemetery is an area of trees, and a glance eventually be a network of 22 communities reveals that they are distinct from those in the Northeast and Midwest United growing in a natural, haphazard fashion in States. The Believers, as they called the nearby Nature Preserve. Evenly spaced themselves, had broken away from the in rows that are still visible, these are apple Quakers in Manchester, England in the trees. They are the remains of an orchard 1750s. They had radical ideas for the time: planted well over 200 years ago. the equality of men and women and of all races, adherence to pacifism, a belief that Both the pond, which once served as a mill celibacy was the only way to achieve a pure pond, and this orchard were created and life and salvation, the confession of sins, a tended by the people who now rest in the devotion to work and collaboration as a adjacent cemetery, which dates from 1785. -

The Shaker Claim to America

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hamilton Digital Commons (Hamilton College) American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 6 Number 2 Pages 93-111 April 2012 “The mighty hand of overruling providence”: The Shaker Claim to America Jane F. Crosthwaite Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq Part of the American Studies Commons This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. “The mighty hand of overruling providence”: The Shaker Claim to America Cover Page Footnote Portions of this paper were delivered at the Communal Studies Association meeting at the Shaker Village at South Union at Auburn, Kentucky, on September 30, 2011. A Winterthur Research Fellowship allowed me to complete research on this project. This articles and features is available in American Communal Societies Quarterly: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq/vol6/iss2/6 Crosthwaite: “The mighty hand of overruling providence” “The mighty hand of overruling providence”: The Shaker Claim to America1 By Jane F. Crosthwaite Since Ann Lee and her small band of followers landed in New York in 1774, they and the Believers who came after them have been objects of curiosity for their American neighbors; they have known derision, respect, fear, and interested wonder. They were viewed as heretics, but saw themselves as orthodox; they were persecuted but saw themselves as triumphant. They built separate communities, but expected the world’s people to unite with them. -

Community, Equality, Simplicity, and Charity the Hancock Shaker Village

Community, equality, simplicity, and charity Studying and visiting various forms of religion gives one a better insight to the spiritual, philosophical, physical, cultural, social, and psychological understanding about human behavior and the lifestyle of a particular group. This photo program is about the Hancock Shaker Village, a National Historic Landmark in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The Village includes 20 historic buildings on 750 acres. The staff provide guests with a great deal of insight to the spiritual practices and life among the people called Shakers. Their famous round stone barn is a major attraction at the Village. It is a marvelous place to learn about Shaker life. BACKGROUND “The Protestant Reformation and technological advances led to new Christian sects outside of the Catholic Church and mainstream Protestant denominations into the 17th and 18th centuries. The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, commonly known as the Shakers, was a Protestant sect founded in England in 1747. The French Camisards and the Quakers, two Protestant denominations, both contributed to the formation of Shaker beliefs.” <nps.gov/articles/history-of-the-shakers.htm> “In 1758 Ann Lee joined a sect of Quakers, known as the Shakers, that had been heavily influenced by Camisard preachers. In 1770 she was imprisoned in Manchester for her religious views. During her brief imprisonment, she received several visions from God. Upon her release she became known as “Mother Ann.” “In 1772 Mother Ann received another vision from God in the form of a tree. It communicated that a place had been prepared for she and her followers in America.