The Legacies of Clara Endicott Sears/ Megan M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright (C) 2005 Fruitlands Museum, Harvard, Massachusetts Permission to Publish from This Material Should Be Discussed with the Museum Curator

Guide to the Transcendentalist Manuscript Collection, Fruitlands Museum, Harvard, Massachusetts www.fruitlands.org REGISTER MS T.1 S. Margaret Fuller Ossoli (1810-1850) Papers, ca 1836-1850 Size: 2 Linear inches Acquisition: Materials were purchased from The Goodspeed Book Shop by Clara Endicott Sears BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH S. Margaret Fuller Ossoli (May 23, 1810-July 19, 1850) was a well known author, lecturer, and Transcendentalist in the Nineteenth Century. She is often called a "bluestocking", because of her feminist beliefs and unconventional life. She was born Sarah Margaret Fuller, the first of nine children of Timothy and Margaret Fuller of Cambridgeport, Massachusetts. Her father was determined to give her a masculine education according to the classical curriculum of the day. The exacting and regimental education began at a very young age and was to take a great toll on her health. But it also gave her abroad knowledge of literature and languages. Following the completion of her formal studies, Margaret gained entrance into the intellectual circles of Cambridge and Harvard. Here she formed lasting friendships with many New England intellectuals. In 1836, Margaret Fuller was hired to teach languages at Bronson Alcott's Temple School. She stayed only a year, but continued her teaching career in Providence Rhode Island at the Greene Street School. In 1839, she returned to Massachusetts and began conducting "Conversations" for society women and others in Boston. At this time, Margaret Fuller also became an integral part of the Transcendentalist Movement. From 1840 to 1842 she edited and contributed to the Transcendentalist journal, The Dial. In 1845, she published her feminist work, Woman in the Nineteenth Century. -

Me0330data.Pdf

SABBATHDAY LAKE SHAKER VILLAGE HABS ME-227 State Route 26, two miles south of the junction with State Route 122 HABS ME-227 New Gloucester vicinity Cumberland County Maine PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY SABBATHDAY LAKE SHAKER VILLAGE HABS No. ME-227 Location: State Route 26, two miles south of the junction with State Route 122 New Gloucester vicinity, Cumberland County, Maine The village is located on the east and west sides of State Route 26 Note: For shelving purposes at the Library of Congress, Cumberland County was selected as the main location for Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village. A portion of the village is also located in Androscoggin County. USGS Gray, Mechanic Falls, Minot, Raymond, Maine Quadrangles Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates (NAD83): NW 38711.37 4874057.31 NE 393479.37 487057.18 SE 393477.82 4868742.10 SW 387411.86 486742.35 Present Owner: The Shaker Society (The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing) Present Occupant: Members of the Shaker Society Present Use: Communal Shaker working village and museum Significance: This is the world’s only remaining active Shaker village community that reflects the evolution of Shaker religion and architecture from the late eighteenth century to the present. SABBATHDAY LAKE SHAKER VILLAGE HABS No. ME-227 (Page 2) PART I: HISTORICAL INFORMATION A. HISTORICAL CONTEXT 1. Historical Development: The United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing at Sabbathday Lake, Maine is the world's only remaining active Shaker community. -

GO Pass User Benefits at Trustees Properties with an Admission Fee

GO Pass User Benefits at Trustees Properties with an Admission Fee Trustees Property Non-Member Admission Member Admission GO Pass Admission Appleton Grass Rides $5 Parking Kiosk Free $5 Parking Kiosk Ashley House $5 House Tour/Grounds Free Free Free Bartholomew’s Cobble $5 Adult/ $1 Child (6-12) + $5 Free Free + $5 Parking Kiosk Parking Kiosk Bryant Homestead $5 General House Tour Free Free Cape Poge $5 Adult/ Child 15 and under free Free Free Castle Hill* $10 Grounds + Tour Admission Grounds Free/Discounted Tours Grounds Free/ Discounted Tours Chesterfield Gorge $2 Free Free Crane Beach* Price per car/varies by season Up to 50% discounted admission Up to 50% discounted admission Fruitlands Museum $14 Adult/Child $6 Free Free Halibut Point $5 Parking w/MA plate per DCR Free (display card on dash) $5 Parking w/MA plate per DCR Little Tom Mountain $5 Parking w/MA plate per DCR $5 Parking w/MA plate per DCR $5 Parking w/MA plate per DCR Long Point Beach $10 Per Car + $5 Per Adult Free Admission + 50% off Parking Free Admission + 50% off Parking Misery Island – June thru Labor $5 Adult/ $3 Child Free Free Day Mission House $5 Free Free Monument Mountain $5 Parking Kiosk Free $5 Parking Kiosk Naumkeag $15 Adult (age 15+) Free Free Notchview – on season skiing $15 Adult/ $6 Child (6-12) Wknd: $8 A/ $3 C | Wkdy: Free Wknd: $8 A/ $3 C | Wkdy: Free Old Manse $10 A/ $5 C/ $9 SR+ST/ $25 Family Free Free Rocky Woods $5 Parking Kiosk Free $5 Parking Kiosk Ward Reservation $5 Parking Kiosk Free $5 Parking Kiosk Wasque – Memorial to Columbus $5 Parking + $5 Per Person Free Free World’s End $6 Free Free *See separate pricing sheets for detailed pricing structure . -

Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection, 1771-1933

THE TRUSTEES OF RESERVATIONS ARCHIVES & RESEARCH CENTER Guide to Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection, 1771-1933 FM.MS.S.Coll.1 by Anne Mansella & Sarah Hayes August 2018 The processing of this collection was funded in part by Mass Humanities, which receives support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and is an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Archives & Research Center 27 Everett Street, Sharon, MA 02067 www.thetrustees.org [email protected] 781-784-8200 The Trustees of Reservations – www.thetrustees.org Date Contents Box Folder/Item No. Extent: 15 boxes (includes 2 oversize boxes) Linear feet: 15 Copyright © 2018 The Trustees of Reservations ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION PROVENANCE Manuscript materials were first acquired by Clara Endicott Sears beginning in 1918 for her Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Massachusetts. Materials continued to be collected by the museum throughout the 20th century. In 2016, Fruitlands Museum became The Trustees’ 116th reservation, and the Shaker manuscript materials were relocated to the Archives & Research Center in Sharon, Massachusetts. In Harvard, the Fruitlands Museum site continues to display the objects that Sears collected. The museum features three separate collections of significant Shaker, Native American, and American art and artifacts, as well as a historic farmhouse that was once home to the family of Louisa May Alcott and is recognized as a National Historic Landmark. OWNERSHIP & LITERARY RIGHTS The Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection is the physical property of The Trustees of Reservations. Literary rights, including copyright, belong to the authors or their legal heirs and assigns. RESTRICTIONS ON ACCESS This collection is open for research. Some items may be restricted due to handling condition of materials. -

1998 New England Archaeology ELECTED MEMBERS

Conference on _CNEA STEERING COMMITTEE 1997-1998 New England Archaeology ELECTED MEMBERS TERM EXPIRES 1998: TERM EXPIRES 1999: NEWSLETTER JOHN PRETOLA (Chair) DAVID SCHAFER (Chair-Elect) Springfield Science Museum Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Volume 17 April 1998 220 State Street Ethnology Springfield, MA 01103 11 Divinity A venne 413-263-6800 x320 Cambridge, MA 02138 CONTENTS Fax: 413-263-6884 617-496-3702 Fax: 617-495-7535 EllEN P. BERKLAND email: [email protected] ARCHAEOLOGY AND HUMAN BIOLOGICAL VARIATION Boston City Archaeologist Environment D~partment EDWARD L. BELL Boston City Hall . Massachusetts Historical Commission Contributed commentary by Alan Goodman .................... 1 Boston, MA 02201 Massachusetts Archives Building 617-635-3852 220 Morrisey Boulevard CONFERENCE ON NEW ENGLAND ARCHAEOLOGY Fax: 617-635-3435 Boston, MA 02125 (617) 727-8470 x359 LUCIANNE LA YIN Fax: (617) 727-5128 1998 ANNUAL MEETING .................................. 9 Archaeological Research Specialists 437 Broad Street EllEN-ROSE SA VULIS Meriden, cr 06450 Department of Anduopolo gy ABSTRACTS ..............................•............ 12 203-237-4777 University of Massachusetts Fax: 203-237-4667 Amherst, MA 01003 413-256-0594 CURRENT RESEARCH ................................... 16 Fax: 413-545-9494 email: [email protected] RHODE ISLAND .................................... 16 MASSACHUSETTS ................................... 18 APPOINTED MEMBERS: MAINE ............................................. 30 NEW HAMPSHIRE .................................. -

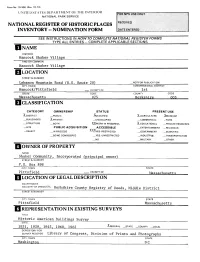

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ INAME HISTORIC Hancock Shaker Village__________________________________ AND/ORCOMMON Hancock Shaker Village STREET & NUMBER Lebanon Mountain Road ("U.S. Route 201 —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Hancock/Pittsfield _. VICINITY OF 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Berkshire 003 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT _PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED X_AGRICULTURE -XMUSEUM __BUILDING(S) X.RRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE __BOTH XXWORK IN PROGRESS ^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS XXXYES . RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Shaker Community, Incorporated fprincipal owner) STREET& NUMBER P.O. Box 898 CITY. TOWN STATE Pittsfield VICINITY OF Mas s achus e 1.1. LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEoaETc. Berkshire County Registry of Deeds, Middle District STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Pittsfield Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1931, 1959, 1945, 1960, 1962 ^FEDERAL _STATE _COUNTY ._LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY, TOWN STATE Washington DC DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X_EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED .^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XXALTERED - restored —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Hancock Shaker Village is located on a 1,000-acre tract of land extending north and south of Lebanon Mountain Road (U.S. -

Trustee's Building, Canterbury Shaker Village

NEW HAMPSHIRE DIVISION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES State of New Hampshire, Department of Cultural Resources 603-271-3483 19 Pillsbury Street, 2 nd floor, Concord NH 03301-3570 603-271-3558 Voice/ TDD ACCESS: RELAY NH 1-800-735-2964 FAX 603-271-3433 http://www.nh.gov/nhdhr [email protected] REPORT ON THE TRUSTEES’ BUILDING CANTERBURY SHAKER VILLAGE CANTERBURY, NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES L. GARVIN 18 NOVEMBER 2001 Summary: The Trustees’ Building or office of the Church Family at Canterbury Shaker Village was the chief point of contact and commerce between the Church Family and the World. The building was the first and only brick structure built by the Church Family, and was constructed of materials of exceptional quality and workmanship. Built with fine bricks that were manufactured by the Shakers, the Trustees’ Building reveals much about the Shakers’ skill as brickmakers and as masons. The Trustees’ Building is a structure of statewide significance in the history of masonry construction in New Hampshire. Although built between 1830 and 1832, when the federal style was quickly waning and giving way to the Greek Revival in neighboring communities, the Trustees’ Building is stylistically conservative. Its interior detailing reflects the federal style, as modified and refined by the Shakers, more fully than any other structure at the village and perhaps more fully than any other Shaker building in New Hampshire. The structure therefore possesses stylistic significance as a document of the Shakers’ adoption and modification of an architectural style that was prevalent in the World. The building’s significance in technology, workmanship, and style would make the structure individually eligible for the National Register of Historic Places if it were evaluated alone. -

Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection, 1771-1933 FM.MS.S

• THE TRUSTEES OF RESERVATIONS ARCHIVES & RESEARCH CENTER Guide to Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection, 1771-1933 FM.MS.S.Coll.1 by Anne Mansella & Sarah Hayes August 2018 The processing of this collection was funded in part by Mass Humanities, which receives support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and is an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Archives & Research Center 27 Everett Street, Sharon, MA 02067 www.thetrustees.org [email protected] 781-784-8200 The Trustees of Reservations – www.thetrustees.org Date Contents Box Folder/Item No. Extent: 15 boxes (includes 2 oversize boxes) Linear feet: 15 Copyright © 2018 The Trustees of Reservations ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION PROVENANCE Manuscript materials were first acquired by Clara Endicott Sears beginning in 1918 for her Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Massachusetts. Materials continued to be collected by the museum throughout the 20th century. In 2016, Fruitlands Museum became The Trustees’ 116th reservation, and the Shaker manuscript materials were relocated to the Archives & Research Center in Sharon, Massachusetts. In Harvard, the Fruitlands Museum site continues to display the objects that Sears collected. The museum features three separate collections of significant Shaker, Native American, and American art and artifacts, as well as a historic farmhouse that was once home to the family of Louisa May Alcott and is recognized as a National Historic Landmark. OWNERSHIP & LITERARY RIGHTS The Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection is the physical property of The Trustees of Reservations. Literary rights, including copyright, belong to the authors or their legal heirs and assigns. RESTRICTIONS ON ACCESS This collection is open for research. Some items may be restricted due to handling condition of materials. -

Supplement to the History and Social Science Curriculum Framework

Resources for History and Social Science Draft Supplement to the 2018 Massachusetts History and Social Science Curriculum Framework Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education May 15, 2018 Copyediting incomplete This document was prepared by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Board of Elementary and Secondary Education Members Mr. Paul Sagan, Chair, Cambridge Mr. Michael Moriarty, Holyoke Mr. James Morton, Vice Chair, Boston Mr. James Peyser, Secretary of Education, Milton Ms. Katherine Craven, Brookline Ms. Mary Ann Stewart, Lexington Dr. Edward Doherty, Hyde Park Dr. Martin West, Newton Ms. Amanda Fernandez, Belmont Ms. Hannah Trimarchi, Chair, Student Advisory Ms. Margaret McKenna, Boston Council, Marblehead Jeffrey C. Riley, Commissioner and Secretary to the Board The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, an affirmative action employer, is committed to ensuring that all of its programs and facilities are accessible to all members of the public. We do not discriminate on the basis of age, color, disability, national origin, race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation. Inquiries regarding the Department’s compliance with Title IX and other civil rights laws may be directed to the Human Resources Director, 75 Pleasant St., Malden, MA, 02148, 781-338-6105. © 2018 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Permission is hereby granted to copy any or all parts of this document for non-commercial educational purposes. Please credit the “Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education.” Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education 75 Pleasant Street, Malden, MA 02148-4906 Phone 781-338-3000 TTY: N.E.T. Relay 800-439-2370 www.doe.mass.edu Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education 75 Pleasant Street, Malden, Massachusetts 02148-4906 Telephone: (781) 338-3000 TTY: N.E.T. -

Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God

American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 9 Number 1 Pages 3-39 January 2015 Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God Stephen J. Paterwic Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq Part of the American Studies Commons This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. Paterwic: Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God Voices That Heard and Accepted the Call of God By Stephen J. Paterwic A review of: Shaker Autobiographies, Biographies and Testimonies, 1806-1907, edited by Glendyne R. Wergland and Christian Goodwillie. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2014. 3 volume set. Let the Shakers Speak for Themselves In 1824 teenager Mary Antoinette Doolittle felt drawn to the Shakers and sought every opportunity to obtain information about them. By chance, while visiting her grandmother, she encountered two young women who had just left the New Lebanon community. “Mary” was thrilled with the opportunity to hear them tell their story.1 Suddenly “something like a voice” said to her, “Why listen to them? Go to the Shakers, visit, see and learn for yourself who and what they are!”2 This idea is echoed in the testimony of Thomas Stebbins of Enfield, Connecticut, who was not satisfied to hear about the Shakers. “But I had a feeling to go and see them, and judge for myself.” (1:400) Almost two hundred years later, this is still the best advice for people seeking to learn about the Shakers. -

The Brahmins, the Irish and the Boston Police Strike of 1919

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2011 Stratified Boston: The rB ahmins, the Irish and the Boston Police Strike of 1919 Sarah Block Bucknell University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Block, Sarah, "Stratified Boston: The rB ahmins, the Irish and the Boston Police Strike of 1919" (2011). Honors Theses. 6. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/6 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iv Acknowledgments This thesis would not have been possible without the help of a few individuals who supported me throughout the thesis preparation and writing process. First, I would like to thank Professor John Enyeart, who both served as my thesis adviser as well as a member of my defense committee. His expert advice in the field of history and writing has aided me immensely, and he helped me turn this thesis into the best work I have completed during my undergraduate career. Similarly, Professor Leslie Patrick and Professor Chris Ellis acted as the second and third readers of my thesis and as the remainder of my defense committee. I could not have completed this work without their guidance. I am appreciative of the time and dedication all of my readers in helping me through this process, and I could not have done it without all of you. -

Hidden Treasures 2017 Flyer

CELEBRATING THE HIDDEN TREASURES OF FREEDOM’S WAY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA DISCOVER l EXPLORE l LEARN l CONNECT l FIND MAY 1 through MAY 31, 2017 www.DiscoverHiddenTreasures.org Complete program information, updates and event registration information. Presenting Sponsor Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area works in partnership with the National Park Service Hidden Treasures 2017 v ABOUT Hidden Treasures is a month-long Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area celebration of the natural, cultural and Designated by Congress for its unique nationally significant qualities historic resources located with the and resources, the Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area is a place Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area. where a combination of natural, cultural, historic and recreational It provides an opportunity to explore resources have shaped a cohesive, nationally distinctive landscape. “treasures” hidden in plain site through Its story is intimately tied to the character of the land as well as those family friendly, community organized and who shaped and were shaped by it. presented programs and activities Home to Minute Man National Historical Park and Walden Pond, offered free of charge. the heritage area is steeped in concepts of individual freedom and responsibility, community cooperation, direct democracy, idealism, DISCOVER exciting and unexpected stories and places within the heritage and social betterment, perspectives that have inspired national and international movements in governance, education, abolitionism, area’s 45 communities. social justice, conservation and the arts. the region’s landscape, public EXLORE The Freedom’s Way Heritage Association is the local coordinating monuments, historic buildings, agricultural entity for the 45 communities within the heritage area.