The "Not-So-Faithful" Believers: Conversion, Deconversion, and Reconversion Among the Shakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of a Shaker Bible

Inspiration, Revelation, and Scripture: The Story of a Shaker Bible STEPHEN J. STEIN OR MORE than two hundred years the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, a religious commu- Fnity commonly known as the Shakers, has been involved with publishing. In 1790 'the first printed statement of Shaker theology' appeared anonymously in Bennington, Vermont, under the imprint of 'Haswell & Russell." Entitied A Concise Statement of the Principles of the Only True Church, according to the Gospel of the Present Appearance of Christ, this publication marked a departure from the pattern established by the founder, Ann Lee, an Englishwoman who came to America in 1774. Lee, herself illiter- ate, feared fixed statements of behef, and forbade her followers to write such documents. Within the space of two decades, however, the Shakers rejected Lee's counsel and turned with increasing fre- quency to the printing press in order to defend themselves against Earlier versions of this essay were presented at the Museum of Our National Heritage, Lexington, Massachusetts (1993), at the annual meeting of the American Society of Church History in San Erancisco (1994), and at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio (1995), under the auspices of the Arthur C. Wickenden Memorial Lectureship. My special thanlcs to Jerry Grant, who shared some of his research notes dealing with the Sacred Roll, which I have used in this version of the essay. I. See Mary L. Richmond, Shaker Literature: A Bibliography (2 vols., Hancock, Mass.: Shaker Community, Inc., 1977), i: 145-46. Richmond echoes the common judgment con- cerning the authorship of this tract, attributing it to Joseph Meacham, an early American convert to Shakerism. -

VALID BAPTISM Advisory List Prepared by the Worship Office and the Metropolitan Tribunal for the Archdiocese of Detroit

249 VALID BAPTISM Advisory list prepared by the Worship Office and the Metropolitan Tribunal for the Archdiocese of Detroit African Methodist Episcopal Patriotic Chinese Catholics Amish Polish National Church Anglican (valid Confirmation too) Ancient Eastern Churches Presbyterians (Syrian-Antiochian, Coptic, Reformed Church Malabar-Syrian, Armenian, Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Ethiopian) Day Saints (since 2001 known as the Assembly of God Community of Christ) Baptists Society of Pius X Christian and Missionary Alliance (followers of Bishop Marcel Lefebvre) Church of Christ United Church of Canada Church of God United Church of Christ Church of the Brethren United Reformed Church of the Nazarene Uniting Church of Australia Congregational Church Waldesian Disciples of Christ Zion Eastern Orthodox Churches Episcopalians – Anglicans LOCAL DETROIT AREA COMMUNITIES Evangelical Abundant Word of Life Evangelical United Brethren Brightmoor Church Jansenists Detroit World Outreach Liberal Catholic Church Grace Chapel, Oakland Lutherans Kensington Community Methodists Mercy Rd. Church, Redford (Baptist) Metropolitan Community Church New Life Ministries, St. Clair Shores Old Catholic Church Northridge Church, Plymouth Old Roman Catholic Church DOUBTFUL BAPTISM….NEED TO INVESTIGATE EACH Adventists Moravian Lighthouse Worship Center Pentecostal Mennonite Seventh Day Adventists DO NOT CELEBRATE BAPTISM OR HAVE INVALID BAPTISM Amana Church Society National David Spiritual American Ethical Union Temple of Christ Church Union Apostolic -

Handbook of Religious Beliefs and Practices

STATE OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES 1987 FIRST REVISION 1995 SECOND REVISION 2004 THIRD REVISION 2011 FOURTH REVISION 2012 FIFTH REVISION 2013 HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES INTRODUCTION The Department of Corrections acknowledges the inherent and constitutionally protected rights of incarcerated offenders to believe, express and exercise the religion of their choice. It is our intention that religious programs will promote positive values and moral practices to foster healthy relationships, especially within the families of those under our jurisdiction and within the communities to which they are returning. As a Department, we commit to providing religious as well as cultural opportunities for offenders within available resources, while maintaining facility security, safety, health and orderly operations. The Department will not endorse any religious faith or cultural group, but we will ensure that religious programming is consistent with the provisions of federal and state statutes, and will work hard with the Religious, Cultural and Faith Communities to ensure that the needs of the incarcerated community are fairly met. This desk manual has been prepared for use by chaplains, administrators and other staff of the Washington State Department of Corrections. It is not meant to be an exhaustive study of all religions. It does provide a brief background of most religions having participants housed in Washington prisons. This manual is intended to provide general guidelines, and define practice and procedure for Washington State Department of Corrections institutions. It is intended to be used in conjunction with Department policy. While it does not confer theological expertise, it will, provide correctional workers with the information necessary to respond too many of the religious concerns commonly encountered. -

Common Labor, Common Lives: the Social Construction of Work in Four Communal Societies, 1774-1932 Peter Andrew Hoehnle Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2003 Common labor, common lives: the social construction of work in four communal societies, 1774-1932 Peter Andrew Hoehnle Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hoehnle, Peter Andrew, "Common labor, common lives: the social construction of work in four communal societies, 1774-1932 " (2003). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 719. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/719 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Common labor, common lives: The social construction of work in four communal societies, 1774-1932 by Peter Andrew Hoehnle A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Agricultural History and Rural Studies Program of Study Committee: Dorothy Schwieder, Major Professor Pamela Riney-Kehrberg Christopher M. Curtis Andrejs Plakans Michael Whiteford Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2003 © Copyright Peter Andrew Hoehnle, 2003. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3118233 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

PILLS. Certain of the De- RADWATS PILLS Dta for He Left a Very Fortunu to His Fire Sons, Deer of Divorce, from Ber Haiband, the DR

& MKDICIXES. MERCHANDISE, &u. Productloa of Beetroot Sujrnr lions of Minister and those of Deputy will MEKCtlANDlSE, &0. SUGA1! & MOLASSES. LEGAL NOTICES. In CierBiuay. establish between the Chamber and my Government; the presence of all the Min- X880 H&-waii- an SOMETHING WORTH READING! isters in the Chamber ; the deliberation in Itiao Suprome Court of the I "When at Cologne, we were told that the Council of affairs ; a un- R,K SLB 33L Air. State sincere JUST RECEIVED Islands. the late Joest had th merit of derstanding with will consti- the Erst minafictory for the the majority, EX tute for the country all the guarantees Kuhllanl. ts. Usury O. Tarks Divorce. re&ninar of foreign sorars, and afterwards v fn. which we seek iu our common solicitude. CompIniBMBt CASTLE & COOKE for the extraction of ssgar from tho bcot- - 1869 W1IK11B.VS, the la I have already proved several times how 2L Wood, entitled cause, bas filed a u W. root, anu reamng uie suptr uuuian. disposed I was." for tho public interest, to petition unto the Honorable A. S. llartwell, ARE business had proved so lucrative that l"he renounce my prerogatives. FROM BREMEN, Jnitlce of tho Supreme Court, praying for a PILLS. certain of The De- RADWATS PILLS Dta For he left a very fortunu to his fire sons, deer of divorce, from ber haiband, the DR. hrp modifications which have decided to pro- A Large Merchan- Stocaacb, Bowels, and 3"oxj3t which them individually several I and Varied Assortment of fendant aforesaid, on the grounds of willful EKiMif the Littr. -

The Origins of Millerite Separatism

The Origins of Millerite Separatism By Andrew Taylor (BA in History, Aurora University and MA in History, University of Rhode Island) CHAPTER 1 HISTORIANS AND MILLERITE SEPARATISM ===================================== Early in 1841, Truman Hendryx moved to Bradford, Pennsylvania, where he quickly grew alienated from his local church. Upon settling down in his new home, Hendryx attended several services in his new community’s Baptist church. After only a handful of visits, though, he became convinced that the church did not believe in what he referred to as “Bible religion.” Its “impiety” led him to lament, “I sometimes almost feel to use the language [of] the Prophecy ‘Lord, they have killed thy prophets and digged [sic] down thine [sic] altars and I only am left alone and they seek my life.”’1 His opposition to the church left him isolated in his community, but his fear of “degeneracy in the churches and ministers” was greater than his loneliness. Self-righteously believing that his beliefs were the “Bible truth,” he resolved to remain apart from the Baptist church rather than attend and be corrupted by its “sinful” influence.2 The “sinful” church from which Hendryx separated himself was characteristic of mainstream antebellum evangelicalism. The tumultuous first decades of the nineteenth century had transformed the theological and institutional foundations of mainstream American Protestantism. During the colonial era, American Protestantism had been dominated by the Congregational, Presbyterian, and Anglican churches, which, for the most part, had remained committed to the theology of John Calvin. In Calvinism, God was envisioned as all-powerful, having predetermined both the course of history and the eternal destiny of all humans. -

Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection, 1771-1933 FM.MS.S

• THE TRUSTEES OF RESERVATIONS ARCHIVES & RESEARCH CENTER Guide to Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection, 1771-1933 FM.MS.S.Coll.1 by Anne Mansella & Sarah Hayes August 2018 The processing of this collection was funded in part by Mass Humanities, which receives support from the Massachusetts Cultural Council and is an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Archives & Research Center 27 Everett Street, Sharon, MA 02067 www.thetrustees.org [email protected] 781-784-8200 The Trustees of Reservations – www.thetrustees.org Date Contents Box Folder/Item No. Extent: 15 boxes (includes 2 oversize boxes) Linear feet: 15 Copyright © 2018 The Trustees of Reservations ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION PROVENANCE Manuscript materials were first acquired by Clara Endicott Sears beginning in 1918 for her Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Massachusetts. Materials continued to be collected by the museum throughout the 20th century. In 2016, Fruitlands Museum became The Trustees’ 116th reservation, and the Shaker manuscript materials were relocated to the Archives & Research Center in Sharon, Massachusetts. In Harvard, the Fruitlands Museum site continues to display the objects that Sears collected. The museum features three separate collections of significant Shaker, Native American, and American art and artifacts, as well as a historic farmhouse that was once home to the family of Louisa May Alcott and is recognized as a National Historic Landmark. OWNERSHIP & LITERARY RIGHTS The Fruitlands Shaker Manuscript Collection is the physical property of The Trustees of Reservations. Literary rights, including copyright, belong to the authors or their legal heirs and assigns. RESTRICTIONS ON ACCESS This collection is open for research. Some items may be restricted due to handling condition of materials. -

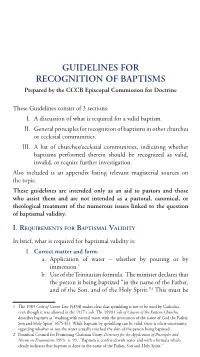

Guidelines for Recognition of Baptisms

First Church of Christ, Scientist Unitarian Universalist I (Mary Baker Eddy) - no baptism I Unitarians I Foursquare Gospel Church V United Church of Christ V General Assembly of Spiritualists I United Church of Canada V Hephzibah Faith Missionary Association I United Reformed V House of David Church I United Society of Believers I Iglesia ni Kristo (Phillippines) I Uniting Church in Australia V GUIDELINES FOR Independent Church of Filipino Christians I Universal Emancipation Church I RECOGNITION OF BAPTISMS Jehovah’s Witnesses (Watchtower Society) I Waldensian V Liberal Catholic Church V Worldwide Church of God (invalid before mid-1990’s) I Prepared by the CCCB Episcopal Commission for Doctrine Lutheran V Zion V Masons / Freemasons - no baptism I These Guidelines consist of 3 sections: Mennonite Churches ? I. A discussion of what is required for a valid baptism. APPENDIX: SOME MAGISTERIAL SOURCES TO BE CONSULTED Methodist V II. General principles for recognition of baptisms in other churches Metropolitan Community Church ? 1983 Code of Canon Law, n. 849-878. or ecclesial communities. Moonies (Reunification Church) I 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, n. 672-691. III. A list of churches/ecclesial communities, indicating whether Moravian Church ? Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity,Directory for the baptisms performed therein should be recognized as valid, National David Spiritual Temple of Christ Church Union I Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism, 1993, n. 92-101. invalid, or require further investigation. National Spiritualist Association I Catechism of the Catholic Church, n. 1213-1284. Also included is an appendix listing relevant magisterial sources on The New Church I the topic. -

Origin and History of Seventh-Day Adventists, Vol. 1

Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists FRONTISPIECE PAINTING BY HARRY ANDERSON © 1949, BY REVIEW AND HERALD As the disciples watched their Master slowly disappear into heaven, they were solemnly reminded of His promise to come again, and of His commission to herald this good news to all the world. Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists VOLUME ONE by Arthur Whitefield Spalding REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. COPYRIGHT © 1961 BY THE REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. OFFSET IN THE U.S.A. AUTHOR'S FOREWORD TO FIRST EDITION THIS history, frankly, is written for "believers." The reader is assumed to have not only an interest but a communion. A writer on the history of any cause or group should have suffi- cient objectivity to relate his subject to its environment with- out distortion; but if he is to give life to it, he must be a con- frere. The general public, standing afar off, may desire more detachment in its author; but if it gets this, it gets it at the expense of vision, warmth, and life. There can be, indeed, no absolute objectivity in an expository historian. The painter and interpreter of any great movement must be in sympathy with the spirit and aim of that movement; it must be his cause. What he loses in equipoise he gains in momentum, and bal- ance is more a matter of drive than of teetering. This history of Seventh-day Adventists is written by one who is an Adventist, who believes in the message and mission of Adventists, and who would have everyone to be an Advent- ist. -

Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith

American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 5 Number 3 Pages 11-137 July 2011 Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith Galen Beale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq Part of the American Studies Commons This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. Beale: Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith By Galen Beale And as she turned and looked at an apple tree in full bloom, she exclaimed: — How beautiful this tree looks now! But some of the apples will soon fall off; some will hold on longer; some will hold on till they are half grown and will then fall off; and some will get ripe. So it is with souls that set out in the way of God. Many set out very fair and soon fall away; some will go further, and then fall off, some will go still further and then fall; and some will go through.1 New England was a hotbed of discontent in the second half of the eighteenth century. Both civil and religious events stirred its citizenry to action. Europeans wished to govern this new, resource-rich country, causing continual fighting, and new religions were springing up in reaction to the times. The French and Indian War had aligned the British with the colonists, but that alliance soon dissolved as the British tried to extract from its colonists the cost of protecting them. -

NBMAA Anything but Simple Press Release

The New Britain Museum of American Art Presents Anything but Simple: Shaker Gift Drawings and the Women Who Made Them August 6, 2020-January 10, 2021 NEW BRITAIN, CONN., August 3, 2020, As a part of the 2020/20+ Women @ NBMAA initiative, The New Britain Museum of American Art (NBMAA) is thrilled to present Anything but Simple: Shaker Gift Drawings and the Women Who Made Them, August 6, 2020 through January 10, 2021. Organized by Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield, MA, Anything but Simple features rare Shaker “gift” or “spirit” drawings created by Shaker women in the mid-1800s, a period known as the Era of Manifestations. During that time, members of Shaker society created dances, songs, and drawings inspired by spiritual revelations or supernatural “gifts.” Colorful, decorative, and complex, “gift” drawings expressed messages of love, dedication to Shaker belief, and the promise of heaven following the earthly journey. Anything but Simple presents 25 of the 200 gift drawings extant in public and private collections today. This group of drawings, made between 1843 and 1857, is widely considered one of the world’s finest collections and includes the most famous gift drawing in existence: Hannah Cohoon’s 1854 Tree of Life. The Shaker Soul The drawings were made by young Shaker women dubbed “instruments” by their elders due to the fact that the women claimed they received these images as gifts from the spirit world. It is perhaps not surprising that a religion founded by a woman should find significant spiritual messages coming from women, even a century before women won the right to vote in the United States. -

The Church Family Orchard of the Watervliet Shaker Community

The Church Family Orchard of the Watervliet Shaker Community Elizabeth Shaver Illustrations by Elizabeth Lee PUBLISHED BY THE SHAKER HERITAGE SOCIETY 25 MEETING HOUSE ROAD ALBANY, N. Y. 12211 www.shakerheritage.org MARCH, 1986 UPDATED APRIL, 2020 A is For Apple 3 Preface to 2020 Edition Just south of the Albany International called Watervliet, in 1776. Having fled Airport, Heritage Lane bends as it turns from persecution for their religious beliefs from Ann Lee Pond and continues past an and practices, the small group in Albany old cemetery. Between the pond and the established the first of what would cemetery is an area of trees, and a glance eventually be a network of 22 communities reveals that they are distinct from those in the Northeast and Midwest United growing in a natural, haphazard fashion in States. The Believers, as they called the nearby Nature Preserve. Evenly spaced themselves, had broken away from the in rows that are still visible, these are apple Quakers in Manchester, England in the trees. They are the remains of an orchard 1750s. They had radical ideas for the time: planted well over 200 years ago. the equality of men and women and of all races, adherence to pacifism, a belief that Both the pond, which once served as a mill celibacy was the only way to achieve a pure pond, and this orchard were created and life and salvation, the confession of sins, a tended by the people who now rest in the devotion to work and collaboration as a adjacent cemetery, which dates from 1785.