Thomas Merton and the Shakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of a Shaker Bible

Inspiration, Revelation, and Scripture: The Story of a Shaker Bible STEPHEN J. STEIN OR MORE than two hundred years the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, a religious commu- Fnity commonly known as the Shakers, has been involved with publishing. In 1790 'the first printed statement of Shaker theology' appeared anonymously in Bennington, Vermont, under the imprint of 'Haswell & Russell." Entitied A Concise Statement of the Principles of the Only True Church, according to the Gospel of the Present Appearance of Christ, this publication marked a departure from the pattern established by the founder, Ann Lee, an Englishwoman who came to America in 1774. Lee, herself illiter- ate, feared fixed statements of behef, and forbade her followers to write such documents. Within the space of two decades, however, the Shakers rejected Lee's counsel and turned with increasing fre- quency to the printing press in order to defend themselves against Earlier versions of this essay were presented at the Museum of Our National Heritage, Lexington, Massachusetts (1993), at the annual meeting of the American Society of Church History in San Erancisco (1994), and at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio (1995), under the auspices of the Arthur C. Wickenden Memorial Lectureship. My special thanlcs to Jerry Grant, who shared some of his research notes dealing with the Sacred Roll, which I have used in this version of the essay. I. See Mary L. Richmond, Shaker Literature: A Bibliography (2 vols., Hancock, Mass.: Shaker Community, Inc., 1977), i: 145-46. Richmond echoes the common judgment con- cerning the authorship of this tract, attributing it to Joseph Meacham, an early American convert to Shakerism. -

VALID BAPTISM Advisory List Prepared by the Worship Office and the Metropolitan Tribunal for the Archdiocese of Detroit

249 VALID BAPTISM Advisory list prepared by the Worship Office and the Metropolitan Tribunal for the Archdiocese of Detroit African Methodist Episcopal Patriotic Chinese Catholics Amish Polish National Church Anglican (valid Confirmation too) Ancient Eastern Churches Presbyterians (Syrian-Antiochian, Coptic, Reformed Church Malabar-Syrian, Armenian, Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Ethiopian) Day Saints (since 2001 known as the Assembly of God Community of Christ) Baptists Society of Pius X Christian and Missionary Alliance (followers of Bishop Marcel Lefebvre) Church of Christ United Church of Canada Church of God United Church of Christ Church of the Brethren United Reformed Church of the Nazarene Uniting Church of Australia Congregational Church Waldesian Disciples of Christ Zion Eastern Orthodox Churches Episcopalians – Anglicans LOCAL DETROIT AREA COMMUNITIES Evangelical Abundant Word of Life Evangelical United Brethren Brightmoor Church Jansenists Detroit World Outreach Liberal Catholic Church Grace Chapel, Oakland Lutherans Kensington Community Methodists Mercy Rd. Church, Redford (Baptist) Metropolitan Community Church New Life Ministries, St. Clair Shores Old Catholic Church Northridge Church, Plymouth Old Roman Catholic Church DOUBTFUL BAPTISM….NEED TO INVESTIGATE EACH Adventists Moravian Lighthouse Worship Center Pentecostal Mennonite Seventh Day Adventists DO NOT CELEBRATE BAPTISM OR HAVE INVALID BAPTISM Amana Church Society National David Spiritual American Ethical Union Temple of Christ Church Union Apostolic -

Handbook of Religious Beliefs and Practices

STATE OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES 1987 FIRST REVISION 1995 SECOND REVISION 2004 THIRD REVISION 2011 FOURTH REVISION 2012 FIFTH REVISION 2013 HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES INTRODUCTION The Department of Corrections acknowledges the inherent and constitutionally protected rights of incarcerated offenders to believe, express and exercise the religion of their choice. It is our intention that religious programs will promote positive values and moral practices to foster healthy relationships, especially within the families of those under our jurisdiction and within the communities to which they are returning. As a Department, we commit to providing religious as well as cultural opportunities for offenders within available resources, while maintaining facility security, safety, health and orderly operations. The Department will not endorse any religious faith or cultural group, but we will ensure that religious programming is consistent with the provisions of federal and state statutes, and will work hard with the Religious, Cultural and Faith Communities to ensure that the needs of the incarcerated community are fairly met. This desk manual has been prepared for use by chaplains, administrators and other staff of the Washington State Department of Corrections. It is not meant to be an exhaustive study of all religions. It does provide a brief background of most religions having participants housed in Washington prisons. This manual is intended to provide general guidelines, and define practice and procedure for Washington State Department of Corrections institutions. It is intended to be used in conjunction with Department policy. While it does not confer theological expertise, it will, provide correctional workers with the information necessary to respond too many of the religious concerns commonly encountered. -

PILLS. Certain of the De- RADWATS PILLS Dta for He Left a Very Fortunu to His Fire Sons, Deer of Divorce, from Ber Haiband, the DR

& MKDICIXES. MERCHANDISE, &u. Productloa of Beetroot Sujrnr lions of Minister and those of Deputy will MEKCtlANDlSE, &0. SUGA1! & MOLASSES. LEGAL NOTICES. In CierBiuay. establish between the Chamber and my Government; the presence of all the Min- X880 H&-waii- an SOMETHING WORTH READING! isters in the Chamber ; the deliberation in Itiao Suprome Court of the I "When at Cologne, we were told that the Council of affairs ; a un- R,K SLB 33L Air. State sincere JUST RECEIVED Islands. the late Joest had th merit of derstanding with will consti- the Erst minafictory for the the majority, EX tute for the country all the guarantees Kuhllanl. ts. Usury O. Tarks Divorce. re&ninar of foreign sorars, and afterwards v fn. which we seek iu our common solicitude. CompIniBMBt CASTLE & COOKE for the extraction of ssgar from tho bcot- - 1869 W1IK11B.VS, the la I have already proved several times how 2L Wood, entitled cause, bas filed a u W. root, anu reamng uie suptr uuuian. disposed I was." for tho public interest, to petition unto the Honorable A. S. llartwell, ARE business had proved so lucrative that l"he renounce my prerogatives. FROM BREMEN, Jnitlce of tho Supreme Court, praying for a PILLS. certain of The De- RADWATS PILLS Dta For he left a very fortunu to his fire sons, deer of divorce, from ber haiband, the DR. hrp modifications which have decided to pro- A Large Merchan- Stocaacb, Bowels, and 3"oxj3t which them individually several I and Varied Assortment of fendant aforesaid, on the grounds of willful EKiMif the Littr. -

The Origins of Millerite Separatism

The Origins of Millerite Separatism By Andrew Taylor (BA in History, Aurora University and MA in History, University of Rhode Island) CHAPTER 1 HISTORIANS AND MILLERITE SEPARATISM ===================================== Early in 1841, Truman Hendryx moved to Bradford, Pennsylvania, where he quickly grew alienated from his local church. Upon settling down in his new home, Hendryx attended several services in his new community’s Baptist church. After only a handful of visits, though, he became convinced that the church did not believe in what he referred to as “Bible religion.” Its “impiety” led him to lament, “I sometimes almost feel to use the language [of] the Prophecy ‘Lord, they have killed thy prophets and digged [sic] down thine [sic] altars and I only am left alone and they seek my life.”’1 His opposition to the church left him isolated in his community, but his fear of “degeneracy in the churches and ministers” was greater than his loneliness. Self-righteously believing that his beliefs were the “Bible truth,” he resolved to remain apart from the Baptist church rather than attend and be corrupted by its “sinful” influence.2 The “sinful” church from which Hendryx separated himself was characteristic of mainstream antebellum evangelicalism. The tumultuous first decades of the nineteenth century had transformed the theological and institutional foundations of mainstream American Protestantism. During the colonial era, American Protestantism had been dominated by the Congregational, Presbyterian, and Anglican churches, which, for the most part, had remained committed to the theology of John Calvin. In Calvinism, God was envisioned as all-powerful, having predetermined both the course of history and the eternal destiny of all humans. -

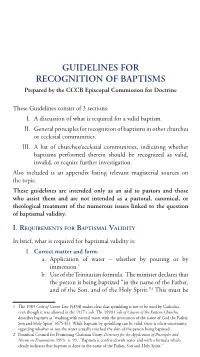

Guidelines for Recognition of Baptisms

First Church of Christ, Scientist Unitarian Universalist I (Mary Baker Eddy) - no baptism I Unitarians I Foursquare Gospel Church V United Church of Christ V General Assembly of Spiritualists I United Church of Canada V Hephzibah Faith Missionary Association I United Reformed V House of David Church I United Society of Believers I Iglesia ni Kristo (Phillippines) I Uniting Church in Australia V GUIDELINES FOR Independent Church of Filipino Christians I Universal Emancipation Church I RECOGNITION OF BAPTISMS Jehovah’s Witnesses (Watchtower Society) I Waldensian V Liberal Catholic Church V Worldwide Church of God (invalid before mid-1990’s) I Prepared by the CCCB Episcopal Commission for Doctrine Lutheran V Zion V Masons / Freemasons - no baptism I These Guidelines consist of 3 sections: Mennonite Churches ? I. A discussion of what is required for a valid baptism. APPENDIX: SOME MAGISTERIAL SOURCES TO BE CONSULTED Methodist V II. General principles for recognition of baptisms in other churches Metropolitan Community Church ? 1983 Code of Canon Law, n. 849-878. or ecclesial communities. Moonies (Reunification Church) I 1990 Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, n. 672-691. III. A list of churches/ecclesial communities, indicating whether Moravian Church ? Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity,Directory for the baptisms performed therein should be recognized as valid, National David Spiritual Temple of Christ Church Union I Application of Principles and Norms on Ecumenism, 1993, n. 92-101. invalid, or require further investigation. National Spiritualist Association I Catechism of the Catholic Church, n. 1213-1284. Also included is an appendix listing relevant magisterial sources on The New Church I the topic. -

Origin and History of Seventh-Day Adventists, Vol. 1

Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists FRONTISPIECE PAINTING BY HARRY ANDERSON © 1949, BY REVIEW AND HERALD As the disciples watched their Master slowly disappear into heaven, they were solemnly reminded of His promise to come again, and of His commission to herald this good news to all the world. Origin and History of Seventh-day Adventists VOLUME ONE by Arthur Whitefield Spalding REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. COPYRIGHT © 1961 BY THE REVIEW AND HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION WASHINGTON, D.C. OFFSET IN THE U.S.A. AUTHOR'S FOREWORD TO FIRST EDITION THIS history, frankly, is written for "believers." The reader is assumed to have not only an interest but a communion. A writer on the history of any cause or group should have suffi- cient objectivity to relate his subject to its environment with- out distortion; but if he is to give life to it, he must be a con- frere. The general public, standing afar off, may desire more detachment in its author; but if it gets this, it gets it at the expense of vision, warmth, and life. There can be, indeed, no absolute objectivity in an expository historian. The painter and interpreter of any great movement must be in sympathy with the spirit and aim of that movement; it must be his cause. What he loses in equipoise he gains in momentum, and bal- ance is more a matter of drive than of teetering. This history of Seventh-day Adventists is written by one who is an Adventist, who believes in the message and mission of Adventists, and who would have everyone to be an Advent- ist. -

New Religious Movements

SYLLABUS RELI 320-01 New Religious Movements Instructor: Jeffrey L. Richey, Ph.D. The University of Findlay (Private comprehensive university) 1000 North Main Street Findlay, Ohio 45840 E-mail: [email protected] Course level and type: Intermediate-level undergraduate survey Hours of Instruction: 3 hours/week x 14 weeks Enrollment: 25 students Last Taught: Spring 2001 Pedagogical Reflections: The goal of this course is to introduce undergraduate students -- most of whom are approaching graduation, and most of whom are not pursuing religious studies as their primary concentration - to the basic theoretical and practical problems encountered in the cross-cultural study of new religious movements. Lectures selectively summarize theoretical perspectives introduced in the Hexham and Poewe textbook, while a wide variety of primary source materials and secondary scholarship is used to "incarnate" abstract concepts from the textbook. Seminar-style discussion dominates most class meetings. The course is organized into three sequential components: (1) introduction to theoretical foundations for the study of new religious movements, (2) cross-cultural case studies (early Christianity, the Shakers, Tenrikyo, Nazareth Baptist Church, Falun Gong), and (3) a concluding case study of the Branch Davidians and the incidents at Waco, Texas, in the spring of 1993, which culminates in a "mock trial" of the parties to the Waco affair, staged in class. In general, the students found the Hexham and Poewe textbook useful, although I encountered several problems with it. The textbook adopts a history-of-religions, "secular" perspective for the most part, but veers off into theological evaluations in its concluding chapters. Moreover, the text's dependence on its authors' highly particular field researches sometimes makes their conclusions appear idiosyncratic or limited to specific contexts. -

The Dream Refinery: Psychics, Spirituality and Hollywood in Los Angeles

The Dream Refinery: Psychics, Spirituality and Hollywood in Los Angeles by Spencer Dwight Orey Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Louise Meintjes, Supervisor ___________________________ Engseng Ho ___________________________ Charles Piot ___________________________ Priscilla Wald Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 ABSTRACT The Dream Refinery: Psychics, Spirituality and Hollywood in Los Angeles by Spencer Dwight Orey Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Louise Meintjes, Supervisor ___________________________ Engseng Ho ___________________________ Charles Piot ___________________________ Priscilla Wald An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 Copyright by Spencer Dwight Orey 2016 Abstract This ethnography examines the relationship between mass-mediated aspirations and spiritual practice in Los Angeles. Creative workers like actors, producers, and writers come to L.A. to pursue dreams of stardom, especially in the Hollywood film and television media industries. For most, a “big break” into their chosen field remains perpetually out of reach despite their constant efforts. Expensive workshops like acting classes, networking events, and chance encounters are seen as keys to Hollywood success. Within this world, rumors swirl of big breaks for devotees in the city’s spiritual and religious organizations. For others, it is in consultations with local spiritual advisors like professional psychics that they navigate everyday decisions of how to achieve success in Hollywood. -

Adventist Heritage Loma Linda University Publications

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Adventist Heritage Loma Linda University Publications Spring 1995 Adventist Heritage - Vol. 16, No. 3 Adventist Heritage, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/advent-heritage Part of the History Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Adventist Heritage, Inc., "Adventist Heritage - Vol. 16, No. 3" (1995). Adventist Heritage. http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/advent-heritage/33 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Loma Linda University Publications at TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Adventist Heritage by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 4 8 D • D THI: TWENTY- THREE. HUNDRED DAYI. B.C.457 3 \1• ~ 3 \11 14 THE ONE W lEEK. A ~~~@ ~im~ J~ ~~ ~& ~ a ~ill ' viS IONS ~ or DANIEL 6 J8HN. Sf.YOITU·D AY ADVENTIST PU BUSKIN ' ASSOCIATIO N. ~ATTIJ: CRHK. MlCJ{!GAfl. Editor-in-Chief Ronald D. Graybill La Sierra Unit•ersi ty Associate Editor Dorothy Minchin-Comm La ierra Unit•er ity Gary Land Andrews University Managing Editor Gary Chartier La Sierra University Volume 16, Number 3 Spring 1995 Letters to the Editor 2 The Editor's Stump 3 Gary Chartier Experience 4 The Millerite Experience: Charles Teel, ]r. Shared Symbols Informing Timely Riddles? Sanctuary 9 The Journey of an Idea Fritz Guy Reason 14 "A Feast of Reason" Anne Freed The Appeal of William Miller's Way of Reading the Bible Obituary 22 William Miller: An Obituary Evaluation of a Life Frederick G. -

200 Religion

200 200 Religion Beliefs, attitudes, practices of individuals and groups with respect to the ultimate nature of existences and relationships within the context of revelation, deity, worship Including public relations for religion Class here comparative religion; religions other than Christianity; works dealing with various religions, with religious topics not applied to specific religions; syncretistic religious writings of individuals expressing personal views and not claiming to establish a new religion or to represent an old one Class a specific topic in comparative religion, religions other than Christianity in 201–209. Class public relations for a specific religion or aspect of a religion with the religion or aspect, e.g., public relations for a local Christian church 254 For government policy on religion, see 322 See also 306.6 for sociology of religion See Manual at 130 vs. 200; also at 200 vs. 100; also at 201–209 and 292–299 SUMMARY 200.1–.9 Standard subdivisions 201–209 Specific aspects of religion 210 Philosophy and theory of religion 220 Bible 230 Christianity 240 Christian moral and devotional theology 250 Local Christian church and Christian religious orders 260 Christian social and ecclesiastical theology 270 History, geographic treatment, biography of Christianity 280 Denominations and sects of Christian church 290 Other religions > 200.1–200.9 Standard subdivisions Limited to comparative religion, religion in general .1 Systems, scientific principles, psychology of religion Do not use for classification; class in 201. -

Religions of America New Religions for a New Land: Trace Religious Developments and Movements Unique to America

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. Religions of America New Religions For A New Land: Trace Religious Developments And Movements Unique To America Founded on the ideal of freedom, North America had a unique role as a birthplace for and spread of new religious movements. This new land provided religious dissenters the opportunity to originate or significantly reshape movements that would become cornerstones of faith for years to come. Religions of America presents scholars and researchers with more than 660,000 pages of content that follow the development of religions and religious movements born in the U.S. from 1820 to 1990. Derived from numerous collections, most notably the American Religions Collection at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Religions of America traces the history and unique characteristics of movements through manuscripts, pamphlets, newsletters, ephemera, and visuals. Various Sources. Primary Source Media. Religions of America. EMPOWER™ RESEARCH ESTEEMED RESOURCES PROVIDE IN-DEPTH RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES This new resource focuses on nineteenth-century movements from Pentecostalism and Mormonism to modern Judeo-Christian organisations (Christian Science, Messianic Judaism) and non-Christian New Thought and Neopagan religions. It also provides robust coverage of alternative, lesser-known, but culturally important religious traditions, including New Age, Neopagan, Wicca, neo-Christian movements (Adventism, Christian Science), and Christian Identity and Fundamentalist movements. Religions of America draws on a variety of collections, including the largest multi-religious collection of its kind, assembled by J. Gordon Melton, the premiere scholar of twentieth-century American and Canadian religious life. Cross searchable with other Gale Primary Sources digital archives, Religions of America is comprised of several key collections: The American Religions Collection includes materials from Hebrew Christians and Pentecostal groups to Baptist organisations and Grace Gospel organisations.