Sudan: Country Report the Situa�On in Darfur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darfur Genocide

Darfur genocide Berkeley Model United Nations Welcome Letter Hi everyone! Welcome to the Darfur Historical Crisis committee. My name is Laura Nguyen and I will be your head chair for BMUN 69. This committee will take place from roughly 2006 to 2010. Although we will all be in the same physical chamber, you can imagine that committee is an amalgamation of peace conferences, UN meetings, private Janjaweed or SLM meetings, etc. with the goal of preventing the Darfur Genocide and ending the War in Darfur. To be honest, I was initially wary of choosing the genocide in Darfur as this committee’s topic; people in Darfur. I also understood that in order for this to be educationally stimulating for you all, some characters who committed atrocious war crimes had to be included in debate. That being said, I chose to move on with this topic because I trust you are all responsible and intelligent, and that you will treat Darfur with respect. The War in Darfur and the ensuing genocide are grim reminders of the violence that is easily born from intolerance. Equally regrettable are the in Africa and the Middle East are woefully inadequate for what Darfur truly needs. I hope that understanding those failures and engaging with the ways we could’ve avoided them helps you all grow and become better leaders and thinkers. My best advice for you is to get familiar with the historical processes by which ethnic brave, be creative, and have fun! A little bit about me (she/her) — I’m currently a third-year at Cal majoring in Sociology and minoring in Data Science. -

Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 Highlights

Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 UNICEF and partners assess damage to communities in southern Khartoum. Sudan was significantly affected by heavy flooding this summer, destroying many homes and displacing families. @RESPECTMEDIA PlPl Reporting Period: July-September 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers • Flash floods in several states and heavy rains in upriver countries caused the White and Blue Nile rivers to overflow, damaging households and in- 5.39 million frastructure. Almost 850,000 people have been directly affected and children in need of could be multiplied ten-fold as water and mosquito borne diseases devel- humanitarian assistance op as flood waters recede. 9.3 million • All educational institutions have remained closed since March due to people in need COVID-19 and term realignments and are now due to open again on the 22 November. 1 million • Peace talks between the Government of Sudan and the Sudan Revolu- internally displaced children tionary Front concluded following an agreement in Juba signed on 3 Oc- tober. This has consolidated humanitarian access to the majority of the 1.8 million Jebel Mara region at the heart of Darfur. internally displaced people 379,355 South Sudanese child refugees 729,530 South Sudanese refugees (Sudan HNO 2020) UNICEF Appeal 2020 US $147.1 million Funding Status (in US$) Funds Fundi received, ng $60M gap, $70M Carry- forward, $17M *This table shows % progress towards key targets as well as % funding available for each sector. Funding available includes funds received in the current year and carry-over from the previous year. 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF’s 2020 Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) appeal for Sudan requires US$147.11 million to address the new and protracted needs of the afflicted population. -

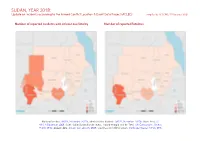

SUDAN, YEAR 2018: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020

SUDAN, YEAR 2018: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 February 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SS- NBS, 1 December 2008; South Sudan/Sudan border status, Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; incident data: ACLED, 22 February 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SUDAN, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 293 124 283 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 151 99 697 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2018 2 Protests 150 4 9 Strategic developments 64 0 0 Methodology 3 Riots 54 12 26 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 30 16 28 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 742 255 1043 Disclaimer 6 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2018 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 22 February 2020). 2 SUDAN, YEAR 2018: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 FEBRUARY 2020 Methodology this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

36 Csos and Individuals Urge the Council to Adopt a Resolution on Sudan

Letter from 36 NGOs and individuals regarding the human rights situation in Sudan in advance of the 33rd session of the UN Human Rights Council To Permanent Representatives of Members and Observer States of the UN Human Rights Council Geneva, Switzerland 7 September 2016 Re: Current human rights and humanitarian situation in Sudan Excellency, Our organisations write to you in advance of the opening of the 33rd session of the United Nations Human Rights Council to share our serious concerns regarding the human rights and humanitarian situation in Sudan. Many of these abuses are detailed in the attached annex. We draw your attention to the Sudanese government’s continuing abuses against civilians in South Kordofan, Blue Nile and Darfur, including unlawful attacks on villages and indiscriminate bombing of civilians. We are also concerned about the continuing repression of civil and political rights, in particular the ongoing crackdown on protesters and abuse of independent civil society and human rights defenders. In a recent example in March 2016, four representatives of Sudanese civil society were intercepted by security officials at Khartoum International Airport on their way to a high level human rights meeting with diplomats that took place in Geneva on 31 March. The meeting was organised by the international NGO, UPR Info, in preparation for the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Sudan that took place in May.1 We call upon your delegation to support the development and adoption of a strong and action- oriented resolution on Sudan under agenda item 4 at the 33rd session of the UN Human Rights Council. -

Convocation - Equity and Aboriginal Issues Committee/Comité Sur L’Équité Et Les Affaires Autochtones Report

Convocation - Equity and Aboriginal Issues Committee/Comité sur l’équité et les affaires autochtones Report TAB 4 Report to Convocation January 29, 2015 Equity and Aboriginal Issues Committee/ Comité sur l’équité et les affaires autochtones Committee Members Julian Falconer, Chair Janet Leiper, Chair Susan Hare, Vice-Chair and Special Liaison with the Access to Justice Committee Beth Symes, Vice-Chair Constance Backhouse Peter Festeryga Avvy Go Howard Goldblatt Jeffrey Lem Marian Lippa Barbara Murchie Judith Potter Susan Richer Purposes of Report: Decision and Information Prepared by the Equity Initiatives Department (Josée Bouchard – 416-947-3984) 68 Convocation - Equity and Aboriginal Issues Committee/Comité sur l’équité et les affaires autochtones Report TABLE OF CONTENTS For Decision Human Rights Monitoring Group Request for Interventions............................................. TAB 4.1 For Information ............................................................................................................. TAB 4.2 Professor Fiona Kay, The Diversification of Career Paths in Law report Reports on the 2014 Survey of Justicia Firms Public Education Equality and Rule of Law Series Calendar 2014 - 2015 69 Convocation - Equity and Aboriginal Issues Committee/Comité sur l’équité et les affaires autochtones Report COMMITTEE PROCESS 1. The Equity and Aboriginal Issues Committee/Comité sur l’équité et les affaires autochtones (the “Committee”) met on January 15, 2015. Committee members Julian Falconer, Chair, Janet Leiper, Chair, Susan Hare, Vice-Chair and Special Liaison with the Access to Justice Committee, Beth Symes, Vice-Chair, Constance Backhouse, Howard Goldblatt, Jeffrey Lem, Marian Lippa, Barbara Murchie, Judith Potter and Susan Richer participated. Sandra Yuko Nishikawa, Chair of the Equity Advisory Group, and Julie Lassonde, representative of the Association des juristes d’expression française de l’Ontario, also participated. -

Why a Minority Rights Approach to Conflict? the Case of Southern Sudan

briefing Why a minority rights approach to conflict? The case of Southern Sudan By Chris Chapman This briefing is aimed at decision-makers working on conflict management, peace-building, development and human rights in countries affected by conflict – whether they be officials of the government in question, humanitarian actors working for donor governments, inter- governmental organizations, local NGOs or international NGOs (the imperfect shorthand of ‘humanitarian actors’ will be used to cover all of these categories). The aim is to illustrate how the minority rights approach can be useful to the work of humanitarian actors in any conflict situation – whether it be aid distribution in a refugee camp, a reformed police force, or a new national education curriculum. For this purpose, the briefing examines the specific case of Southern Sudan. Conflict management requires a holistic approach that addresses all the causes of conflict, and the minority rights approach does not mean addressing only this aspect of conflict. However research carried out by Minority Rights Group International (MRG) has shown that governments and external actors often fail to understand the role that minority rights plays in both the origin and resolution of identity-based conflicts.1 Minority rights provides a framework for humanitarian actors to analyze, understand and address many of the complex issues behind the conflict, and if utilized by the Government of South Sudan (GoSS), can help to build peace based on the accommodation of diversity, through providing all communities with a political voice and equal opportunities to access resources. Southern Sudan provides a complex and demanding case A woman attends a peace conference between the Nuer and Dinka tribes study. -

The Economics of Ethnic Cleansing in Darfur

The Economics of Ethnic Cleansing in Darfur John Prendergast, Omer Ismail, and Akshaya Kumar August 2013 WWW.ENOUGHPROJECT.ORG WWW.SATSENTINEL.ORG The Economics of Ethnic Cleansing in Darfur John Prendergast, Omer Ismail, and Akshaya Kumar August 2013 COVER PHOTO Displaced Beni Hussein cattle shepherds take shelter on the outskirts of El Sereif village, North Darfur. Fighting over gold mines in North Darfur’s Jebel Amer area between the Janjaweed Abbala forces and Beni Hussein tribe started early this January and resulted in mass displacement of thousands. AP PHOTO/UNAMID, ALBERT GONZALEZ FARRAN Overview Darfur is burning again, with devastating results for its people. A kaleidoscope of Janjaweed forces are once again torching villages, terrorizing civilians, and systematically clearing prime land and resource-rich areas of their inhabitants. The latest ethnic-cleans- ing campaign has already displaced more than 300,000 Darfuris this year and forced more than 75,000 to seek refuge in neighboring Chad, the largest population displace- ment in recent years.1 An economic agenda is emerging as a major driver for the escalating violence. At the height of the mass atrocities committed from 2003 to 2005, the Sudanese regime’s strategy appeared to be driven primarily by the counterinsurgency objectives and secondarily by the acquisition of salaries and war booty. Undeniably, even at that time, the government could have only secured the loyalty of its proxy Janjaweed militias by allowing them to keep the fertile lands from which they evicted the original inhabitants. Today’s violence is even more visibly fueled by monetary motivations, which include land grabbing; consolidating control of recently discovered gold mines; manipulating reconciliation conferences for increased “blood money”; expanding protection rackets and smuggling networks; demanding ransoms; undertaking bank robberies; and resum- ing the large-scale looting that marked earlier periods of the conflict. -

North Darfur II

Darfur Humanitarian Profile Annexes: I. North Darfur II. South Darfur III. West Darfur Darfur Humanitarian Profile Annex I: North Darfur North Darfur Main Humanitarian Agencies Table 1.1: UN Agencies Table 1.2: International NGOs Table 1.3: National NGOs Intl. Natl. Vehicl Intl. Natl. Vehic Intl. Natl. Vehic Agency Sector staff staff* es** Agency Sector staff staff* les** Agency Sector staff staff les FAO 10 1 2 2 ACF 9 4 12 3 Al-Massar 0 1 0 Operations, Logistics, Camp IOM*** Management x x x GAA 1, 10 1 3 2 KSCS x x x OCHA 14 1 2 3 GOAL 2, 5, 8, 9 6 117 10 SECS x x x 2, 3, 7, UNDP*** 15 x x x ICRC 12, 13 6 20 4 SRC 1, 2 0 10 3 2, 4, 5, 6, UNFPA*** 5, 7 x x x IRC 9, 10, 11 1 5 4 SUDO 5, 7 0 2 0 Protection, Technical expertise for UNHCR*** site planning x x x MSF - B 5 5 10 0 Wadi Hawa 1 1 x 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, Oxfam - UNICEF 9 11, 12 4 5 4 GB 2, 3, 4 5 30 10 Total 1 14 3 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, UNJLC*** 17 x x x SC-UK 11, 12 5 27 8 Technical Spanish UNMAS*** advice x x x Red Cross 3, 4 1 0 1 UNSECOORD 16 1 1 1 DED*** x x x WFP 1, 9, 11 1 12 5 NRC*** x x x WHO 4, 5, 6 2 7 2 Total 34 224 42 Total 10 29 17 x = information unavailable at this time Sectors: 1) Food 2) Shelter/NFIs 3) Clean water 4) Sanitation 5) Primary Health Facilities *Programme and project staff only. -

AGAINST the GRAIN: the Cereal Trade in Darfur

DECEMBER 2014 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice AGAINST THE GRAIN: The Cereal Trade in Darfur Margie Buchanan-Smith, Abdul Jabar Abdulla Fadul, Abdul Rahman Tahir, Musa Adam Ismail, Nadia Ibrahim Ahmed, Mohamed Zakaria, Zakaria Yagoub Kaja, El Hadi Abdulrahman Aldou, Mohamed Ibrahim Hussein Abdulmawla, Abdalla Ali Hassan, Yahia Mohamed Awad Elkareem, Laura James, Susanne Jaspars Empowered lives. lives. Resilient nations.nations. Cover photo: cereal market in El Fashir ©2014 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, including UNDP, WFP or their Member States. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 114 Curtis Street Somerville, MA 02144 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu 2 Feinstein International Center Acknowledgements The research team would particularly like to -

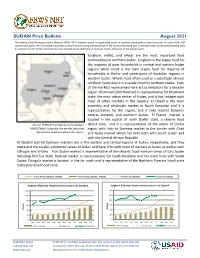

SUDAN Price Bulletin August 2021

SUDAN Price Bulletin August 2021 The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) monitors trends in staple food prices in countries vulnerable to food insecurity. For each FEWS NET country and region, the Price Bulletin provides a set of charts showing monthly prices in the current marketing year in selected urban centers and allowing users to compare current trends with both five-year average prices, indicative of seasonal trends, and prices in the previous year. Sorghum, millet, and wheat are the most important food commodities in northern Sudan. Sorghum is the staple food for the majority of poor households in central and eastern Sudan regions while millet is the main staple food for majority of households in Darfur and some parts of Kordofan regions in western Sudan. Wheat most often used as a substitute all over northern Sudan but it is a staple food for northern states. Each of the markets represented here act as indicators for a broader region. Khartoum (Om Durman) is representative for Khartoum state, the main urban center of Sudan, and it has linkages with most of other markets in the country. El Obeid is the main assembly and wholesale market in North Kordofan and it is representative for the region, and it links market between central, western, and southern Sudan. El Fasher market is located in the capital of north Darfur state, a chronic food Source: FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges deficit area, and it is representative of the entire of Darfur FAMIS/FMoA, Sudan for the market data and region with links to Geneina market in the border with Chad information used to produce this report. -

Unpacking Ethnic Stacking: the Uses and Abuses of Security Force Ethnicity in Sudan

Unpacking Ethnic Stacking: The Uses and Abuses of Security Force Ethnicity in Sudan Nathaniel Allen National Defense University June 2019 1 Abstract African elites commonly recruit co-ethnic soldiers into state security institutions, a practice known as ethnic stacking. Ethnic stacking has recently received considerable attention from scholars and been linked to an array of outcomes, including repression, high levels of political violence and poor democratization outcomes. This article employs evidence from Sudan under Omar Al Bashir to argue that ethnic stacking is not one coherent tactic but several, and that its effects are mediated by the processes through which security force institutions are ethnically stacked. Within the leadership of state security institutions, ethnic stacking in Sudan served as a coup-proofing measure to ensure that leaders bound by ties of kinship and trust maintain oversight over the most sensitive functions of the security apparatus. In Sudan’s militia groups, ethnic stacking of militia groups and rank-and-file soldiers was used as a means of warfare and repression by altering overall composition of security forces with respect to the civilian population. The militia strategy itself was a product of the failure of the regime’s traditional security forces to function as effective counterinsurgents, and, by keeping the periphery of the country in a near-constant state of conflict, prolonged Bashir’s regime. World Count: 9,816 words Keywords: Ethnicity, Sudan, civil-military relations, civil wars, coups 2 Introduction For thirty years, Sudan was ruled by Al Bashir, an army officer who was the longest serving leader of the longest running regime in Sudanese history. -

COUNTRY Food Security Update

SUDAN Food Security Outlook Update April 2017 Food security continues to deteriorate in South Kordofan and Jebel Marra KEY MESSAGES By March/April 2017, food insecurity among IDPs and poor residents in Food security outcomes, April to May 2017 SPLM-N areas of South Kordofan and new IDPs in parts of Jabal Mara in Darfur has already deteriorated to Crisis (IPC Phase 3) and is likely to deteriorate to Emergency (IPC Phase 4) by May/June through September 2017 due to displacement, restrictions on movement and trade flows, and limited access to normal livelihoods activities. Influxes of South Sudanese refugees into Sudan continued in March and April due to persistent conflict and severe acute food insecurity in South Sudan. As March 31, more than 85,000 South Sudanese refugees have arrived into Sudan since the beginning of 2017, raising total number arrived to nearly 380,000 South Sudanese refugees since the start of the conflict in December 2013. Following above-average 2016/17 harvests, staple food prices either remained stable or started increases between February and March, particularly in some arid areas of Darfur and Red Sea states, and South Source: FEWS NET Kordofan, which was affected by dryness in 2016. Prices remained on Projected food security outcomes, June to September average over 45 percent above their respective recent five-year 2017 average. Terms of trade (ToT) between livestock and staple foods prices have started to be in favor of cereal traders and producers since January 2017. CURRENT SITUATION Staple food prices either remained stable or started earlier than anticipated increases, particularly in the main arid and conflicted affected areas of Darfur, Red Sea and South Kordofan states between February and March.