Research Journal of English (RJOE)Vol-6, Issue-2, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S3issue 3.1 March 2021

www.theuniversejournal.com The UNIverse Journal ISSN 2582-6352 An International Quarterly Refereed Open Access e-Journal https://www.theuniversejournal.com/index.php https://www.theuniversejournal.com/edboard.php https://www.theuniversejournal.com/current_issue.php https://www.theuniversejournal.com/join_us.php Issue 3.1 March 2021 1 www.theuniversejournal.com The UNIverse Journal ISSN 2582-6352 An International Quarterly Refereed Open Access e-Journal Shruti Tiwari [email protected] India “ Free to Be You, Free to Be Me ” Disclaimer: This story is a fictionalised account of the epic Mahabharata. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are used in a fictitious manner and no offence to any mythological figure is intended. PROLOGUE 3102 BCE, Outskirts of Dwarka “Are you sure about this, brother?”, asked Dushasana yet again as he cradled his eight glass of wine between his fingers. He shouldn’t be drinking while making crucial decisions, after all, the importance of being at his best game in situations like these was drilled into his head since he was ten. But, right now, he wanted- needed- to escape into oblivion even if it were for a few minutes. “Enough with your doubts. We are doing this. In order to beat those sons of bitches, we need Krishna and we need him before those Pandavas get to him.”, snapped Duryodhana as he paced in circles. He stopped to look around the magnificence of the palace. People were right indeed, the city of Dwarka had something about it. Some called it the abode of the divine but Duryodhana knew better. -

Mahabharata 8

PUBLISHED BY DREAMLAND PUBLICATIONS 4425, NAI SARAK, DELHI-110006 (INDIA) PHONE : 291 5831,292 9770, FAX : 011-514 1327 Art Work by : Retold &. Edited by K.L. VERMA Rs._ 20.00„ _____ T.R. BHANOT Processing : BEST PHOTO LITHO GRAPHERS MAHABHARAT PART 8 PUBLISHED BY DREAMLAND PUBLICATIONS J-128, KIRTI NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110 015 PHONE : 543 5657, 545 5657, FAX : 011-543 8283 The Death-god praised Yudhishthir saying, “ You are great, my son. You have pleased me ignoring your hunger, thirst, sorrow, attachment and also have conquered greed,pride and anger. So, I want to confer the title of D harm rajon you. Also, I want to give you two boons. Ask for what you want.” Yudhishthir asked for his boons as follows : "Sir, we have promised a Brahman to find out his churner and igniting-rod w h i c h h e had lost when a deer took them away on being entangled in its horns. Be kind to bless us so that we may be able to find them out and restore them to the Brahman . As for my second boon, I implore you tolenableus to remain untraced during the thirteenth year of our exile,” remarked Yudhishthir. Hearing Yudhishthir’s words, the Death-god put on a smiling face and said, ‘‘That deer was none else but myself. I had enacted the entire game with a view to testing you. Here are the two things of the Brahman. Take them and restore them to their owner. He will be very pleased to have them back.” Saying these words, the Death-god handed over the churner and igniting-rod to Yudhishthir who felt highly glorified. -

Part 1: the Beginning of Mahabharat

Mahabharat Story Credits: Internet sources, Amar Chitra Katha Part 1: The Beginning of Mahabharat The story of Mahabharata starts with King Dushyant, a powerful ruler of ancient India. Dushyanta married Shakuntala, the foster-daughter of sage Kanva. Shakuntala was born to Menaka, a nymph of Indra's court, from sage Vishwamitra, who secretly fell in love with her. Shakuntala gave birth to a worthy son Bharata, who grew up to be fearless and strong. He ruled for many years and was the founder of the Kuru dynasty. Unfortunately, things did not go well after the death of Bharata and his large empire was reduced to a kingdom of medium size with its capital Hastinapur. Mahabharata means the story of the descendents of Bharata. The regular saga of the epic of the Mahabharata, however, starts with king Shantanu. Shantanu lived in Hastinapur and was known for his valor and wisdom. One day he went out hunting to a nearby forest. Reaching the bank of the river Ganges (Ganga), he was startled to see an indescribably charming damsel appearing out of the water and then walking on its surface. Her grace and divine beauty struck Shantanu at the very first sight and he was completely spellbound. When the king inquired who she was, the maiden curtly asked, "Why are you asking me that?" King Shantanu admitted "Having been captivated by your loveliness, I, Shantanu, king of Hastinapur, have decided to marry you." "I can accept your proposal provided that you are ready to abide by my two conditions" argued the maiden. "What are they?" anxiously asked the king. -

Mahabaratha Tatparya Nirnaya - Introduction by Prof.K.T.Pandurangi

Mahabaratha Tatparya Nirnaya - Introduction by Prof.K.T.Pandurangi Chapter XXVI Drona takes charge as Commander-in-chief On the eleventh day Drona was made the Commander in chief. Karna also joined him. Duryodhana asked Drona to arrest Yudhishtira. Drona initiated a bitter fighting and tried to arrest Yudhishtira. However, Arjuna made a counter attack and failed the effort of Drona arresting Yudhishtira. Bhima also gave a tough fight. On that night Duryodhana expressed his displeasure to Drona for not arresting Yudhishtira. Drona suggested, “If Arjuna was diverted from the main field of the battle Yudhishtira could be arrested”. On the twelfth day Susharma and Samsatakas were asked to take away Arjuna to some other area of the battlefield. Satyaratha, Satyavarma, Satyavrata, Satyeshu and Satyakarma were called Samsaptakas as these had taken an oath to kill Arjuna in the presence of a ritual fire. They took Arjuna in the presence of a ritual fire. They took Arjuna aside and started fighting. In the meanwhile, Duryodhana asked Bhagadatta to confront Bhima. Bhima hit the elephant Supratika of Bhagadatta. Sri Krishna saw this confrontation between Bhima and Bhagadatta. He thought Bhagadatta might employ vaisnavastra which he alone could pacify. Therefore, he started to come to this area with Arjuna. He Samsaptakas tried to prevent Arjuna. He employed Sammohana astra and moved towards Bhagadatta. Arjuna and Bhagadatta started fighting. Bhagadatta employed vaisnavastra. Sri Krishna received it and it became Vaijayanthi mala. Arjuna hit Bhagadatta and his elephant Supratika. Both died, Arjuna killed Achala and Vrishika the two younger brothers of Shakuni. Shakuni employed certain magical weapons. -

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Agnatavasa of Pandavas the Events

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Agnatavasa of Pandavas The events of Virataparva that relate to the agnatavasa of Pandavas are described in 23rd chapter. After completing the twelve years period of Vanavasa Pandavas took leave of Dhaumya, other sages and Brahman’s and made up their mind to undergo agnatavasa. They went to capital city of Virata. Before they entered the city they hid their weapons on a Sami tree in the outskirts of the city. The five Pandavas assumed the form of an ascetic, a cook, a eunuch, a charioteer, and a cowherd respectively. Draupadi assumed the form of Sairandhri i.e. a female artisan. Bhima assumed the form of cook for two reasons i) He never took food prepared by others ii) He did not want to reveal his great knowledge by assuming a Brahmana form. During their Agnatavasa they did not serve Virata or any other person. The younger brothers of Yudhishtira served Lord Hari and their eldest brother Yudhishtira in whom also God was present by the name of Yudhishtira One day a wrestler who had become invincible by the boon of Siva came to Virata's city. The wrestlers maintained by Virata were not able to meet his challenge. The ascetic i.e.Yudhishtira suggested to king Virata that the cook who had the skill in wrestling well could be asked to wrestle with him. The cook i.e., Bhima, wrestled with him and killed. Kichaka is Killed Ten months after Pandava's stay at Virata's palace, Kichaka, the brother of Queen Sudesna came. He was away to conquer the neighboring kings. -

The Mahabharata

BHAGAVAD GITA The Global Dharma for the Third Millennium Appendix Translations and commentaries by Parama Karuna Devi Copyright © 2015 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved. ISBN-13: 978-1517677428 ISBN-10: 1517677424 published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center phone: +91 94373 00906 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com © 2015 PAVAN Correspondence address: PAVAN House Siddha Mahavira patana, Puri 752002 Orissa Gita mahatmya by Adi Shankara VERSE 1 gita: Bhagavad gita; sastram: the holy scripture; idam: this; punyam: accruing religious and karmic merits; yah: one who; pathet: reads; prayatah: when departed; puman: a human being; visnoh: of Vishnu; padam: the feet; avapnoti: attains; bhaya: fear; soka adi: sadness etc; varjitah: completely free. This holy scripture called Bhagavad gita is (the source of) great religious and karmic merits. One who reads it leaves (the materialistic delusion, the imprisonment of samsara, etc)/ after leaving (this body, at the time of death) attains the abode of Vishnu, free from fear and sadness. Parama Karuna Devi VERSE 2 gita adhyayana: by systematic study of Bhagavad gita; silasya: by one who is well behaved; pranayama: controlling the life energy; parasya: of the Supreme; ca: and; na eva: certainly not; santi: there will be; hi: indeed; papani: bad actions; purva: previous; janma: lifetimes; krtani: performed; ca: even. By systematically studying the Bhagavad gita, chapter after chapter, one who is well behaved and controls his/ her life energy is engaged in the Supreme. Certainly such a person becomes free from all bad activities, including those developed in previous lifetimes. VERSE 3 malanih: from impurities; mocanam: liberation; pumsam: a human being; jala: water; snanam: taking bath; dine dine: every day; 4 Appendix sakrid: once only; gita ambhasi: in the waters of the Bhagavad gita; snanam: taking bath; samsara: the cycle of conditioned life; mala: contamination; nasanam: is destroyed. -

Select Stories from Puranas

SELECT STORIES FROM PURANAS Compiled, Composed and Interpreted by V.D.N.Rao Former General Manager of India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India 1 SELECT STORIES FROM PURANAS Contents Page Preface 3 Some Basic Facts common to Puranas 3 Stories related to Manus and Vamshas 5 (Priya Vrata, Varudhini & Pravaraakhya, Swarochisha, Uttama, Tamasa, Raivata, Chakshusa, and Vaiwasvata) The Story of Surya Deva and his progeny 7 Future Manus (Savarnis, Rouchya and Bhoutya) 8 Dhruva the immortal; Kings Vena and Pruthu 9 Current Manu Vaiwasvata and Surya Vamsha 10 (Puranjaya, Yuvanashwa, Purukutsa, Muchukunda, Trishanku, Harischandra, Chyavana Muni and Sukanya, Nabhaga, Pradyumna and Ila Devi) Other famed Kings of Surya Vamsha 14 Origin of Chandra, wedding, Shaapa, re-emergence and his Vamsha (Budha, Pururava, Jahnu, Nahusha, Yayati and Kartaveeryarjuna) 15 Parashurama and his encounter with Ganesha 17 Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Nrisimha, Vamana and Parashurama Avataras 18 Quick retrospective of Ramayana (Birth of Rama, Aranya Vaasa, Ravana Samhara, Rama Rajya, Sita Viyoga, Lava Kusha and Sita-Rama Nidhana) 21 Maha Bharata in brief (Veda Vyasa, Ganga, Bhishma& Pandava-Kauravas & 43 Quick proceedings of Maha Bharata Battle Some doubts in connection with Maha Bharata 50 Episodes related to Shiva and Parvati (Links of Sandhya Devi, Arundhati, Sati and Parvati; Daksha Yagna, Parvati’s wedding, and bitrh of Skanda) 52 Glories of Maha Deva, incarnations, Origin of Shiva Linga, Dwadasha Lingas, Pancha -

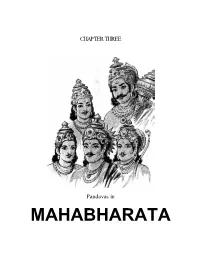

Year III-Chap.3-MAHABHARATA

CHAPTER THREE Pandavas in MAHABHARATA Year III Chapter 3-MAHABHARATA CHANDRA VAMSA The first king of the race of the Moon was PURURAVAS His great grandson l KING YAYATI His sons l l l KING PURU KING YADU One of his descendants His descendants were called Yadavas l l KING DUSHYANT LORD KRISHNA His son l KING BHARATA – one of his descendants l KING KURU One of his descendants l KING SHANTANU His sons l l l l CHITRANGAD VICHITRAVIRYA BHEESHMA His sons l l l DHRITARASHTRA PANDU His 100 sons called after King Kuru as His five sons called after him as l l KAURAVAS PANDAVAS l Arjuna’s grandson KING PARIKSHIT 44 Year III Chapter 3-MAHABHARATA MAHABHARATA Mahabharata is the longest epic poem in the world, originally written in Sanskrit, the ancient language of India. It was composed by Sage Veda Vyasa several thousand years ago. Vyasa dictated the entire epic at a stretch while Lord Ganesha wrote it down for him. The epic has been divided into the following: o ADI PARVA o SABHA PARVA o VANA PARVA o VIRATA PARVA o UDYOGA PARVA o BHEESHMA PARVA o DRONA PARVA o KARNA PARVA o SALYA PARVA / AFTER THE WAR ADI PARVA The story of Mahabharata starts with King Dushyant, a powerful ruler of ancient India. Dushyanta married Shakuntala, the foster-daughter of sage Kanva. Shakuntala was born to Menaka, an apsara (nymph) of Indra's court, and sage Vishwamitra. Shakuntala gave birth to a worthy son Bharata, who grew up to be fearless and strong. It was after his name India came to be known as Bharatavarsha. -

Anga and Adhiratha Royal Descent Brijesh Raised a Query That He Understood That Only the Brahmin and Ksatriya Varnas Were Allowed to Bear Arms

Anga and Adhiratha Royal descent Brijesh raised a query that he understood that only the Brahmin and Ksatriya varnas were allowed to bear arms. .. That statement was never true for Epic India or even later on. .. That statement was hardly even true for Bollywood India for Chambal movies from where it actually comes from. .. Even in the days of Mahabharata, we have Kings and royal dynasts from all Varnas and Jatis. Of course, people keep confusing Varna and Jaati as same. That is understandable but was not true. .. https://www.facebook.com/puransandvedas/posts/609081102565825 . .. The easiest way to state that this was false was the Virata Parva. In Virata Parva when Susharma attacked, Virata rallied all able men who can bear arms. That included Brahmin Kanka, the Gopa Kundali, the Sudra cook Ballava, the Granthika of Vandi the charioteer caste and vaisya Tantripala. .. Even in Epic Age, we have dynasties and Kings belonging to all Gotras and lineages. .. o Kings of Kekaya were from days of King Sardandayana were Sootas being product of a Ksatriya and Brahamni. Their children were famous in Mahabharata and included the Kakaya warriors who fought on both sides, Chekitana, Sudeshna and Keechaka. Keechaka was also Commander-in-chief of the Matsaya armies. o Kings of Matsaya were also descended from daughter of Satyavati and Parasara and Uparicharira Vasu. This was a case of close cousin marriage and also was cross caste marriage. Satyavati’s children were considered Parasaras and technically belonged to Brahmin lineage and Matsaya royal family was Ksatriya. In recent generations from the Mahabharata main lineage, there was King Dhvasan Dvaitavana who is also celebrated later in the Satapatha Brahmana who conducted many Asvamedhas as many as fourteen and was the considered superior to all Brahamans and ksatriyas despite born a soota. -

Kurukshetra War

Kurukshetra War The Kurukshetra War is a Hindu Historical war de- scribed in the Indian epic Mahābhārata as a conflict that arose from a dynastic succession struggle between two groups of cousins of an Indo-Aryan kingdom called Kuru, the Kauravas and Pandavas, for the throne of Hastinapura. It involved a number of ancient kingdoms participating as allies of the rival groups. The location of the battle is described as having occurred in Kurukshetra in the modern state of Haryana in In- dia. The conflict is believed to form an essential com- ponent of an ancient work called Jaya and hence the epic Mahābhārata. Mahābhārata states that the war started on Kartheeka Bahula Amavasya (the end of the Kartheeka and the start The position of the Kuru and Panchala kingdoms in Iron Age of the Margasira lunar month), moon on Jyesta star, on Vedic India Tuesday early morning. A solar eclipse also happened on that day and this Muhurtha was kept by Krishna him- self. The Bhagavad Gita was told on that early morn- ing, before the war began. The war lasted only eighteen days, during which vast armies from all over the Indian (Bharatha) Subcontinent fought alongside the two rivals. Despite only referring to these eighteen days, the war nar- rative forms more than a quarter of the book, suggest- ing its relative importance within the epic, which overall spans decades of the warring families. The narrative describes individual battles of various heroes of both sides, battle-field deaths of some of the prominent heroes, military formations employed on each day by both armies, war diplomacy, meetings and dis- cussions among the heroes and commanders before com- mencement of war on each day and the weapons used. -

Arjuna and His Sons - Two Generations of Courage

Newsletter Archives www.dollsofindia.com Arjuna and His Sons - Two Generations of Courage Copyright © 2019, DollsofIndia The great Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, are true gems that are relevant through all time and for all ages and generations of people. While most of us know and adore the central characters of both the epics, few of us have information regarding the next generation princes and princesses in those epics. The Uttara Ramayana relates in detail the lives of Rama's twins, Lava and Kusha. The legend of the Upapandavas too relates the story of the Pandavas' children. However, this tale is not commonly heard and not many know much about the Pandavas' next generation or what happened to them in the subsequent years. Mahabharata - Set of 3 Volumes (Book) Here is the tale of the offspring of Arjuna, one of the main characters of the Mahabharata. Arjuna Before going into the lives of Arjuna's children, let us go into the life of the Pandava prince. The third of the Pandava brothers, Arjuna was the Son of Indra, the King of the Devas. He was feted as the best archer in the world, during his time. Born to Kunti, the first wife of King Pandu, ruler of the Kuru Kingdom, Arjuna is believed to be a saint named Nara in his previous birth. Nara was the lifelong companion of another saint, Narayana; an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, who manifested in his Krishna avatara. Arjuna was the most famous of the five Pandava brothers. He was born seven months after Lord Krishna was born and their friendship lasted their entire lifetime. -

Mahabharata Tatparya Nirnaya

SRImAdAnAMdatIrthaBagavatpaadaprANIta Mahabharata Tatparya Nirnaya With Original Sanskrit Verses, Kannada translation, Explanation and Special Notes Volume - 4 (Chapters: 22 – 26) Editing, Translation and Explanation By Dr. Vyasanakere Prabhanjanacharya Note: Translation to English by Harshala Rajesh. With permission to translate - from Dr. Vyasanakere Prabhanjanacharya Transliterated Roman Scripts of the Original Shlokas from AHDS London(thanks to Sri Desiraju Hanumantha Rao for providing the same and Sri Srisha Rao et al for Transliterated Roman Scripts) atha trayoviMsho.adhyAyaH Chapter 23 aj~nAtavAsasamAptiH || OM || nArAyaNAnugrahato yathAva nnistIrya tAn.h dvAdashAbdAn.h vane te | visRuijya cha brAhmaNAdIn.h sadhaumyA naj~nAtavAsAya tato mano dadhuH || 23.1|| 1. By the grace of SriHari, after having spent 12 years of stay in the forest, Pandavas decided to say goodbye to Doumya and other Brahmins and start Agnatavasa(Living life incognito) Notes: 1. This means that Pandavas got ready for Agnatavasa after taking leave Doumya, Priests, Rishis and sages who had come in large numbers along with them to the forest. Reference 1.AdishabdEna swavihitAgnihOtrAtithipUjanakShatracihnAdIn | -(ja.) 1.uShitAshca vanE kRucCrE vayaM dwAdasha vatsarAn | aj~jAtavAsasamayaM shEShaM varShaM trayOdasham || tad vasAmO vayaM CannAstadanuj~jAtumarhatha | -BArata (vana. 315/6) purOhitOyamasmAkaM magnihOtrANi rakShatu | sUdapaurOgavaiH sArdhaM drupadasya nivEshanE || iMdrasEnamuKAshcEmE rathAnAdAya kEvalAn | yAMtuM dwAravatIM shIGramiti mE vartatE matiH || imAshca nAryO draupadyAH sarvAshca paricArikAH | pAMcAlAnEva gacCaMtu sUdapaurOgavaiH saha || sarvairapi ca vaktavyaM na prAj~jAyaMta pAMDavaH || gatA hyasmAnapahAya sarvE dwaitavanAditi || -BArata (virATa 4/2-5) gatvA virATasya purIM nidhAya hetIH shamyAM chhannarUpA babhUvuH | yatiH sUdaH shhaNDhaveshho.ashvasUta veshho gopo gandhakartrI cha jAtAH || 23.2|| 2. Pandavas reached the city of Virata, hid their weapons in the Shami tree and changed their appearances.