Archives at the Millennium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gay Marriage Opponents Closer To

Columbia Foundation Articles and Reports July 2012 Arts and Culture ALONZO KING’S LINES BALLET $40,000 awarded in August 2010 for two new world-premiere ballets, a collaboration with architect Christopher Haas (Triangle of the Squinches) and a new work set to Sephardic music (Resin) 1. Isadora Duncan Dance Awards, March 27, 2012 2012 Isadora Duncan Dance Award Winners Announced Christopher Haas wins a 2012 Isadora Duncan Dance Award for Outstanding Achievement in Visual Design for his set design for Triangle of the Squinches. Alonzo King’s LINES Ballet wins two other Isadora Duncan Dance Awards for the production Sheherazade. ASIAN ART MUSEUM $255,000 awarded since 2003, including $50,000 in July 2011 for Phantoms of Asia, the first major exhibition of Asian contemporary art from May 18 to September 2, 2012, which explores the question “What is Asia?” through the lens of supernatural, non-material, and spiritual sensibilities in art of the Asian region 2. San Francisco Chronicle, May 13, 2012 Asian Art Museum's 'Phantoms of Asia' connects Phantoms of Asia features over 60 pieces of contemporary art playing off and connecting with the Asian Art Museum's prized historical objects. According to the writer, Phantoms of Asia, the museum’s first large-scale exhibition of contemporary art is an “an expansive and ambitious show.” Allison Harding, the Asian Art Museum's assistant curator of contemporary art says, “We're trying to create a dialogue between art of the past and art of the present, and look at the way in which artists today are exploring many of the same concerns of artists throughout time. -

Cold War: a Report on the Xviith IAMHIST Conference, 25-31 July 1997, Salisbury MD

After the Fall: Revisioning the Cold War: A Report on the XVIIth IAMHIST Conference, 25-31 July 1997, Salisbury MD By John C. Tibbetts “The past can be seized only as an image,” wrote Walter Benjamin. But if that image is ignored by the present, it “threatens to disappear irretrievably.” [1] One such image, evocative of the past and provocative for our present, appears in a documentary film by the United States Information Agency, The Wall (1963). Midway through its account of everyday life in a divided Berlin, a man is seen standing on an elevation above the Wall, sending out hand signals to children on the other side in the Eastern Sector. With voice communication forbidden by the Soviets, he has only the choreography of his hands and fingers with which to print messages onto the air. Now, almost forty years later, the scene resonates with an almost unbearable poignancy. From the depths of the Cold War, the man seems to be gesturing to us. But his message is unclear and its context obscure. [2] The intervening gulf of years has become a barrier just as impassable as the Wall once was. Or has it? The Wall was just one of dozens of screenings and presentations at the recent “Knaves, Fools, and Heroes: Film and Television Representations of the Cold War”—convened as a joint endeavor of IAMHist and the Literature/Film Association, 25-31 July 1997, at Salisbury State University, in Salisbury, Maryland— that suggested that the Cold War is as relevant to our present as it is to our past. -

Philippines in View Philippines Tv Industry-In-View

PHILIPPINES IN VIEW PHILIPPINES TV INDUSTRY-IN-VIEW Table of Contents PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. MARKET OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. PAY-TV MARKET ESTIMATES ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.3. PAY-TV OPERATORS .......................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4. PAY-TV AVERAGE REVENUE PER USER (ARPU) ...................................................................................................... 7 1.5. PAY-TV CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING ................................................................................................................ 7 1.6. ADOPTION OF DTT, OTT AND VIDEO-ON-DEMAND PLATFORMS ............................................................................... 7 1.7. PIRACY AND UNAUTHORIZED DISTRIBUTION ........................................................................................................... 8 1.8. REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT .............................................................................................................................. -

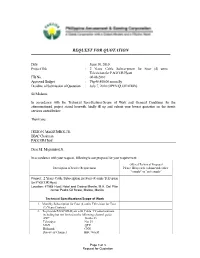

Request for Quotation

REQUEST FOR QUOTATION Date : June 30, 2010 Project Title : 2 Years Cable Subscription for Four (4) units Television for PAGCOR Hyatt ITB No. : 06-08-2010 Approved Budget : Php48,400.00 annually Deadline of Submission of Quotation : July 7, 2010 (OPEN QUOTATION) Sir/Madame: In accordance with the Technical Specifications/Scope of Work and General Conditions for the aforementioned project stated herewith, kindly fill up and submit your lowest quotation on the item/s services stated below. Thank you. DELIO N. MAGSUMBOL JR. BBAC Chairman PAGCOR-Hyatt Dear Mr. Magsumbol Jr.: In accordance with your request, following is our proposal for your requirement: Offered Technical Proposal Description of Service Requirement Please fill up each column with either: “comply” or “not comply” Project: 2 Years Cable Subscription for Four (4) units Television for PAGCOR Hyatt Location: #1588 Hyatt Hotel and Casino Manila, M.H. Del Pilar corner Pedro Gil Street, Malate, Manila Technical Specifications/Scope of Work 1. Monthly Subscription for Four (4) units Television for Two (2) Years Contract 2. To provide PAGCOR-Hyatt with Cable TV entertainment including but not limited to the following channel guide: ANC Studio 23 Teleradyo Net 25 MAX QTV Hallmark CNN Discovery Channel BBC World Page 1 of 3 Request for Quotation Animal Planet Bloomberg MYX Star Sports Cinema One National Geographic Knowledge Channel Cartoon Network Animax Nickelodeon Hero TV Disney Channel NBN4 Star World ABS-CBN AXN TV5 HBO CS9 Star Movies GMA 7 MTV IBC 13 Living Asia 3. The system shall be capable of providing the aforementioned TV channels to all subscribers connected thereto, and such television signals shall be free of noticeable degradation when signals delivered to any subscriber are compared with the television signals impressed upon the transmission system at the point of origin. -

Environment, Trade and Society in Southeast Asia

Environment, Trade and Society in Southeast Asia <UN> Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte (kitlv, Leiden) Henk Schulte Nordholt (kitlv, Leiden) Editorial Board Michael Laffan (Princeton University) Adrian Vickers (Sydney University) Anna Tsing (University of California Santa Cruz) VOLUME 300 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki <UN> Environment, Trade and Society in Southeast Asia A Longue Durée Perspective Edited by David Henley Henk Schulte Nordholt LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 3.0) License, which permits any non-commercial use, distri- bution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of kitlv (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: Kampong Magetan by J.D. van Herwerden, 1868 (detail, property of kitlv). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Environment, trade and society in Southeast Asia : a longue durée perspective / edited by David Henley, Henk Schulte Nordholt. pages cm. -- (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde ; volume 300) Papers originally presented at a conference in honor of Peter Boomgaard held August 2011 and organized by Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-28804-1 (hardback : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-28805-8 (e-book) 1. Southeast Asia--History--Congresses. 2. Southeast Asia--Civilization--Congresses. -

Dynamics of Rural Innovation – a Primer for Emerging Professionals

Jim Woodhill Jim Woodhill (eds.) Rhiannon Pyburn and Feeding the world in a sustainable and fair way is the challenge that a new generation of agricultural professionals must face. This will Dynamics of Rural Innovation demand not just technological solutions but a whole package of social, A PRIMER FOR EMERGING PROFESSIONALS economic, market and political innovations. Central to the challenge is enabling people and organisations with different perspectives and different interests to work creatively together. All this demands new ways of thinking and new sets of competencies. Rhiannon Pyburn and Jim Woodhill (eds.) Dynamics of Rural Innovation This book offers young professionals and students insight into the A PRIMER theory and practice of ‘innovation systems’. It covers important background and concepts, the ‘how to’ of facilitating innovation, and the role of the broader context. The book is about the dynamics of rural innovation – how to work with the changing nature of both the FOR context and people involved in rural innovation processes and how to EMERGING facilitate networks of stakeholders to stimulate innovation. The aim is to support agricultural and rural development professionals, especially young ones, as enablers and facilitators of stakeholder-led innovation. Inspirational stories illustrate how different people – from farmers PROFESSIONALS to extension of cers, business leaders, traders, NGO staff, and policy makers – have collaborated to make new and successful things happen. The Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) and Wageningen University’s Centre for Development Innovation (CDI) bring more than 30 years of experience working with partners in developing countries on agricultural innovation processes and social learning. This book capitalises on these experiences and brings together both conceptual thinkers and practitioners in the writing process to articulate lessons. -

C Ntentasia March 2014

10-23 C NTENTASIA MARCH 2014 www.contentasia.tv l https://www.facebook.com/contentasia facebook.com/contentasia l @contentasia l www.asiacontentwatch.com ESPN deal with Outdoor Channel Exclusive agreement for IndyCar and X Games ESPN and Asia-based TV network, Out- door Channel, have sealed an exclusive pan-regional agreement for IndyCar Series and two X Games franchises – X Games Austin and X Games Aspen – in Southeast Asia, Hong Kong, India, Mon- golia, South Korea and Taiwan, among other markets. The multi-year agreement involves joint promotion and marketing across South- east Asia. While exclusive regionally, deal terms allow for specific individual licens- ing agreements to be negotiated on a country-by-country basis. The deal, which will be announced this week, could be the first of other lin- ear channel collaborations with Outdoor Channel as ESPN moves further into its post-ESPN Star Sports (ESS) era in Asia. Gregg Creevey, the managing director of Outdoor Channel operator Multi Chan- nels Asia’s (MCA), said both properties were hugely successful in the U.S. and presented “enormous potential for growth in the Asia-Pacific region”. MCA’s content agreement with ESPN is part of Outdoor Channel’s 2014 push into more mainstream positioning with, among other shows, Ironman Asia Pacific cham- pionships, Australasian Safari, World Heli Challenge, Wild Spirits and the FIA Asia Pacific Rally Championships. Since the end of the ESPN Star Sports joint venture in 2012, ESPN operated no ESPN-branded linear television channels in Asia. The company’s focus has been digital platforms, including ESPNFC and ESPNcricinfo. -

ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corporation Sgt

ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corporation Sgt. Esguerra Avenue, Quezon City, Philippines April 19, 2010 Philippine Stock Exchange, Inc. Exchange Road, Ortigas Center Pasig City Attention: Ms. Janet A. Encarnacion Head, Disclosure Department Dear Ms. Encarnacion, We hereby submit to the Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE) the Definitive Information Statement of ABS- CBN Broadcasting Corporation (ABS-CBN or the Company). Based on the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) letter dated April 16, 2010, which provided a list of prescribed amendments to the Preliminary Information Statement the Company submitted to the SEC and the PSE last April 13, 2010, we made the following revisions: 1. Updated to March 31, 2010 the following information: a. Number of Shares Outstanding on page 7. b. Security Ownership of Certain Record and Beneficial Owners of more than 5% on page 7. c. Security Ownership of Directors and Management on page 8. d. List of Directors and Executive Officers on pages 9 to 18. e. Top 20 Shareholders on page 50. 2. Disclosure of any relationship of Mr. Oscar M. Lopez with any of the nominees for Independent Director on page 9. 3. Compliance with the five year rotation requirement of external auditor on page 20. 4. Brief reason(s) for and the general effect of the proposed amendment of the Company’s Articles of Incorporation on page 22. 5. Submission of 1st Quarter 2010 report on page 42. 6. Share price information as of the latest practicable trading date (April 19, 2010) on page 49. 7. Disclosure on dividend policy and restrictions on page 49. Thank you. -

The Passion of Max Von Oppenheim Archaeology and Intrigue in the Middle East from Wilhelm II to Hitler

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/163 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Lionel Gossman is M. Taylor Pyne Professor of Romance Languages (Emeritus) at Princeton University. Most of his work has been on seventeenth and eighteenth-century French literature, nineteenth-century European cultural history, and the theory and practice of historiography. His publications include Men and Masks: A Study of Molière; Medievalism and the Ideologies of the Enlightenment: The World and Work of La Curne de Sainte- Palaye; French Society and Culture: Background for 18th Century Literature; Augustin Thierry and Liberal Historiography; The Empire Unpossess’d: An Essay on Gibbon’s “Decline and Fall”; Between History and Literature; Basel in the Age of Burckhardt: A Study in Unseasonable Ideas; The Making of a Romantic Icon: The Religious Context of Friedrich Overbeck’s “Italia und Germania”; Figuring History; and several edited volumes: The Charles Sanders Peirce Symposium on Semiotics and the Arts; Building a Profession: Autobiographical Perspectives on the Beginnings of Comparative Literature in the United States (with Mihai Spariosu); Geneva-Zurich-Basel: History, Culture, and National Identity, and Begegnungen mit Jacob Burckhardt (with Andreas Cesana). He is also the author of Brownshirt Princess: A Study of the ‘Nazi Conscience’, and the editor and translator of The End and the Beginning: The Book of My Life by Hermynia Zur Mühlen, both published by OBP. -

1893.1 H Press SIDON a STUDY in ORIENTAL HISTORY

XiMi '1754. j ICOlUMBlA^ UNIVERSITY 1893.1 h Press SIDON A STUDY IN ORIENTAL HISTORY BY FREDERICK CARL EI8ELEN Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Philosophy Columbia University Nftu fork i00r Tgfts /. IX 1) Copyright 1907 By The Macmillan Company Set up and printed from the type Published, May, 1907 GRATEFULLY DEDICATED TO PROFESSOR RICHARD J. H. GOTTHEIL, Ph.D. TEACHER AND FRIEND 160781 NOTE The Mediterranean Sea is the natural meeting place of the various influences that have proceeded from three continents. The life of those cities that have taken a prominent part in developing the countries on its littoral must always be of interest to the student of history. Each city mirrors not only the general influences that were at work, but adds thereto its special quota of peculiar force. The role played by the Phoenicians, during the generations of their power and influence, as mediators be- tween conflicting interests gives to their history a certain attrac- tion. One of the chief centres of their power was the city of Sidon, and in the present volume of the Columbia University Oriental Series, Dr. F. C. Eiselen has studied the history of that city from the earliest times down to the present day. For this purpose he has gathered together the various references to be found regarding Sidon upon Assyrian and Egyptian monu- ments, in Hebrew literature, in the classical authors, in the records of pilgrims and in the historical works of Mohammedan writers. On account of the nature of the sources, his account of the life of the city must at times be disconnected. -

Etere and ABS-CBN Knowledge Channel

11/12/2008 Press Etere a consistent system Etere and ABS-CBN Knowledge Channel ETERE was the perfect answer for the expansion of the ABS-CBN’s system. Knowledge is the educational channel owned by Creative Programs Inc. (an ABS-CBN subsidiary) that has been following a specific moral goal since its first debut in 1999: foresting “the vision of a community of educated, empowered, and responsible citizens working relentlessly for a better Philippines”. This is Knowledge’s main purpose. Knowledge Channel Obviously, ETERE with its multi-year experience in software solutions, was more than happy to support such an all-worthy motto, and therefore Knowledge. ETERE was the perfect answer for the expansion of the ABS-CBN’s system, especially taking into consideration its capacity to implement such an ambitious project by using all the existing infrastructures (ABS-CBN already runs more than 20 channels). The extreme modularity of ETERE allows you expanding simply by adding the necessary pieces. Its distributed architecture, without a single point of failure, allows easy and unlimited expansion. Knowledge Channel ETERE is a TV management system that is based on a SQL Media Asset Management system, able to integrate all functions inside a media company by automating and linking them together in a single consistent system. ETERE controls the following devices for Knowledge: • INCA Character Generator • 1 SeaChange Videoserver BML/MCL 4012 • n. 1 Quartz router via Etere Sarvaji • 56 computers Thanks to the virtualization of the serial port embedded in ETERE, the 56 PCs can share the same resources even with serial control and with no need of any additional Rs422 Router. -

Knowledge Channel Powers Through Challenging Times Story on Page 4

NOVEMBER 2020 A monthly publication of the Lopez group of companies www.lopezlink.ph http://www.facebook.com/lopezlinkonline www.twitter.com/lopezlinkph Knowledge Channel powers through challenging times Story on page 4 Economic impact assessment Rockwell Kapamilya ‘TVP’ partners with Christmas streams on TGN Realty presents YouTube …page 2 …page 7 …page 8 2 Lopezlink November 2020 BIZ NEWS BIZ NEWS Lopezlink November 2020 3 Virtual corporate governance training First Gen gets DOE award to Rockwell enters partnership By Carla Paras-Sison FGEN LNG preferred tenderers THE annual corporate gover- develop pump storage project with TGN Realty to develop nance training of directors and By Joel Gaborni for binding invitation to officers of publicly listed com- panies (PLCs) associated with FIRST Gen Corporation has always available when it’s security and stability. the Lopez Group went virtual been awarded a hydro service needed,” said Ricky Carandang, The hydro service contract mixed-use community on Oct. 23 as conducted by the contract by the Department of First Gen vice president. “But gives First Gen, through First tender for charter of FSRU Institute of Corporate Direc- Energy to develop a 120-mega- with a pump storage facility Gen Hydro, five years to con- venture with the family be- one bedroom to three bedrooms tors (ICD). watt (MW) pumped-storage like the one we want to build in duct predevelopment stage FGEN LNG Corporation has Ltd. and Höegh LNG Asia construction, ownership and hind the successful Nepo Cen- sized 44 sq. m. to 142 sq. m. The The continuing education hydroelectric facility in Aya, Pantabangan, we will be able to activities—from a preliminary expanded the list of preferred Pte.