Gail-Low-Publishing-Commonwealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malcolm X and United States Policies Towards Africa: a Qualitative Analysis of His Black Nationalism and Peace Through Power and Coercion Paradigms

Malcolm X and United States Policies towards Africa: A Qualitative Analysis of His Black Nationalism and Peace through Power and Coercion Paradigms by Abdul Karim Bangura, Ph.D. [email protected] Researcher-in-Residence, Abrahamic Connections and Islamic Peace Studies at the Center for Global Peace, American University; Director, The African Institution; Professor, Research Methodology and Political Science; Coordinator, National Conference on Undergraduate Research initiative at Howard University, Washington, DC; External Reader of Research Methodology at the Plekhanov Russian University, Moscow; Inaugural Peace Professor for the International Summer School in Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Peshawar in Pakistan; and International Director and Advisor to the Centro Cultural Guanin in Santo Domingo Este, Dominican Republic. The author is also the author of more than 75 books and more than 600 scholarly articles. The winner of more than 50 prestigious scholarly and community service awards, among Bangura’s most recent awards are the Cecil B. Curry Book Award for his African Mathematics: From Bones to Computers; the Diopian Institute for Scholarly Advancement’s Miriam Ma’at Ka Re Award for his article titled “Domesticating Mathematics in the African Mother Tongue” published in The Journal of Pan African Studies (now Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies); the Special United States Congressional Award for “outstanding and invaluable service to the international community;” the International Center for Ethno- Religious Mediation’s Award for his scholarly work on ethnic and religious conflict resolution and peacebuilding, and promotion of peace and conflict resolution in conflict areas; and the Moscow Government Department of Multicultural Policy and Intergrational Cooperation Award for the scientific and practical nature of his work on peaceful interethnic and interreligious relations. -

KYK-OVER-AL Volume 2 Issues 8-10

KYK-OVER-AL Volume 2 Issues 8-10 June 1949 - April 1950 1 KYK-OVER-AL, VOLUME 2, ISSUES 8-10 June 1949-April 1950. First published 1949-1950 This Edition © The Caribbean Press 2013 Series Preface © Bharrat Jagdeo 2010 Introduction © Dr. Michael Niblett 2013 Cover design by Cristiano Coppola Cover image: © Cecil E. Barker All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission. Published by the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports, Guyana at the Caribbean Press. ISBN 978-1-907493-54-6 2 THE GUYANA CLASSICS LIBRARY Series Preface by the President of Guyana, H. E. Bharrat Jagdeo General Editors: David Dabydeen & Lynne Macedo Consulting Editor: Ian McDonald 3 4 SERIES PREFACE Modern Guyana came into being, in the Western imagination, through the travelogue of Sir Walter Raleigh, The Discoverie of Guiana (1595). Raleigh was as beguiled by Guiana’s landscape (“I never saw a more beautiful country...”) as he was by the prospect of plunder (“every stone we stooped to take up promised either gold or silver by his complexion”). Raleigh’s contemporaries, too, were doubly inspired, writing, as Thoreau says, of Guiana’s “majestic forests”, but also of its earth, “resplendent with gold.” By the eighteenth century, when the trade in Africans was in full swing, writers cared less for Guiana’s beauty than for its mineral wealth. Sugar was the poet’s muse, hence the epic work by James Grainger The Sugar Cane (1764), a poem which deals with subjects such as how best to manure the sugar cane plant, the most effective diet for the African slaves, worming techniques, etc. -

Caribbean Voices Broadcasts

APPENDIX © The Author(s) 2016 171 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE BBC CARIBBEAN VOICES BROADCASTS March 11th 1943 to September 7th 1958 © The Author(s) 2016 173 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE BBC CARIBBEAN VOICES EDITORS Una Marson April 1940 to December 1945 Mary Treadgold December 1945 to July 1946 Henry Swanzy July 1946 to November 1954 Vidia Naipaul December 1954 to September 1956 Edgar Mittelholzer October 1956 to September 1958 © The Author(s) 2016 175 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 TIMELINE OF THE WEST INDIES FEDERATION AND THE TERRITORIES INCLUDED January 3 1958 to 31 May 31 1962 Antigua & Barbuda Barbados Dominica Grenada Jamaica Montserrat St. Kitts, Nevis, and Anguilla St. Lucia St. Vincent and the Grenadines Trinidad and Tobago © The Author(s) 2016 177 G.A. Griffi th, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943–1958, New Caribbean Studies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-32118-9 CARIBBEAN VOICES : INDEX OF AUTHORS AND SEQUENCE OF BROADCASTS Author Title Broadcast sequence Aarons, A.L.C. The Cow That Laughed 1369 The Dancer 43 Hurricane 14 Madam 67 Mrs. Arroway’s Joe 1 Policeman Tying His Laces 156 Rain 364 Santander Avenue 245 Ablack, Kenneth The Last Two Months 1029 Adams, Clem The Seeker 320 Adams, Robert Harold Arundel Moody 111 Albert, Nelly My World 496 Alleyne, Albert The Last Mule 1089 The Rock Blaster 1275 The Sign of God 1025 Alleyne, Cynthia Travelogue 1329 Allfrey, Phyllis Shand Andersen’s Mermaid 1134 Anderson, Vernon F. -

The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Poetry Edited by Jahan Ramazani Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-09071-2 — The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Poetry Edited by Jahan Ramazani Frontmatter More Information the cambridge companion to postcolonial poetry The Cambridge Companion to Postcolonial Poetry is the first collection of essays to explore postcolonial poetry through regional, historical, political, formal, textual, gender, and comparative approaches. The essays encompass a broad range of English-speakers from the Caribbean, Africa, South Asia, and the Pacific Islands; the former settler colonies, such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, especially non-Europeans; Ireland, Britain’s oldest colony; and post- colonial Britain itself, particularly black and Asian immigrants and their descen- dants. The comparative essays analyze poetry from across the postcolonial anglophone world in relation to postcolonialism and modernism, fixed and free forms, experimentation, oral performance and creole languages, protest poetry, the poetic mapping of urban and rural spaces, poetic embodiments of sexuality and gender, poetry and publishing history, and poetry’s response to, and reimagining of, globalization. Strengthening the place of poetry in postco- lonial studies, this Companion also contributes to the globalization of poetry studies. jahan ramazani is University Professor and Edgar F. Shannon Professor of English at the University of Virginia. He is the author of five books: Poetry and its Others: News, Prayer, Song, and the Dialogue of Genres (2013); A Transnational Poetics (2009), winner of the 2011 Harry Levin Prize of the American Comparative Literature Association, awarded for the best book in comparative literary history published in the years 2008 to 2010; The Hybrid Muse: Postcolonial Poetry in English (2001); Poetry of Mourning: The Modern Elegy from Hardy to Heaney (1994), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award; and Yeats and the Poetry of Death: Elegy, Self-Elegy, and the Sublime (1990). -

To Read the Abstracts and Biographies for This Panel

Abstracts and Biographies Panel 1: Operable Infrastructures Chair: Mora Beauchamp-Byrd Panel Chair: Mora J. Beauchamp-Byrd, Ph.D., is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Art and Design at The University of Tampa, where she teaches courses in Modern & Contemporary Art and in Museum Studies. An art historian, curator, and arts administrator, she specializes in the art of the African Diaspora; American Art; Modern and Contemporary art, including a focus on late twentieth-century British art; Museum & Curatorial studies; and representations of race, class and gender in American comics. She has organized numerous exhibitions, including Transforming the Crown: African, Asian and Caribbean Artists in Britain, 1966- 1996; Picturing Creole New Orleans: The Photographs of Arthur P. Bedou, and Little Nemo’s Progress: Animation and Contemporary Art. She is currently completing a manuscript that examines David Hockney, Lubaina Himid, and Paula Rego’s appropriations of William Hogarth’s eighteenth-century satirical narratives. From Resistance to Institution: The History of Autograph ABP from 1988 to 2007 Taous R. Dahmani Since its creation in 1988, Autograph ABP has aimed at defending the work and supporting author-photographers from Caribbean, African and Indian diasporas, first in England and then beyond. Initially a utopian idea, then a very practical and political project and finally a hybrid institution, Autograph ABP has presented itself in turn as an association, an agency, an archive, a research centre, a publishing house and an exhibition space. To tell the story of Autograph ABP is to tell the story of its evolution, that of a militant space having become a cultural institution. -

Vol 25 / No. 2 / November 2017 Volume 24 Number 2 November 2017

1 Vol 25 / No. 2 / November 2017 Volume 24 Number 2 November 2017 Published by the discipline of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Self-portrait with projection, October 2017, img_9723 by Rodell Warner Anu Lakhan (copy editor) Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] OR Ms. Angela Trotman Department of Language, Linguistics and Literature Faculty of Humanities, UWI Cave Hill Campus P.O. Box 64, Bridgetown, BARBADOS, W.I. e-mail: [email protected] SUBSCRIPTION RATE US$20 per annum (two issues) or US$10 per issue Copyright © 2017 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Lisa Outar Ian Strachan BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. Edited by full time academics and with minimal funding or institutional support, the Journal originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. -

The Edgar Mittelholzer Memorial Lectures

BEACONS OF EXCELLENCE: THE EDGAR MITTELHOLZER MEMORIAL LECTURES VOLUME 3: 1986-2013 Edited and with an Introduction by Andrew O. Lindsay 1 Edited by Andrew O. Lindsay BEACONS OF EXCELLENCE: THE EDGAR MITTELHOLZER MEMORIAL LECTURES - VOLUME 3: 1986-2013 Preface © Andrew Jefferson-Miles, 2014 Introduction © Andrew O. Lindsay, 2014 Cover design by Peepal Tree Press Cover photograph: Courtesy of Jacqueline Ward All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without permission. Published by the Caribbean Press. ISBN 978-1-907493-67-6 2 Contents: Tenth Series, 1986: The Arawak Language in Guyanese Culture by John Peter Bennett FOREWORD by Denis Williams .......................................... 3 PREFACE ................................................................................. 5 THE NAMING OF COASTAL GUYANA .......................... 7 ARAWAK SUBSISTENCE AND GUYANESE CULTURE ........................................................................ 14 Eleventh Series, 1987. The Relevance of Myth by George P. Mentore PREFACE ............................................................................... 27 MYTHIC DISCOURSE......................................................... 29 SOCIETY IN SHODEWIKE ................................................ 35 THE SELF CONSTRUCTED ............................................... 43 REFERENCES ....................................................................... 51 Twelfth Series, 1997: Language and National Unity by Richard Allsopp CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD -

Conference Schedule

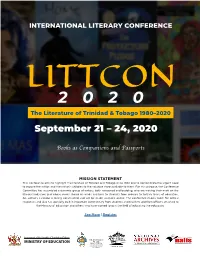

INTERNATIONAL LITERARY CONFERENCE LITTCON2020 The Literature of Trinidad & Tobago 1980–2020 September 21 – 24, 2020 Books as Companions and Passports MISSION STATEMENT This Conference aims to highlight the literature of Trinidad and Tobago since 1980 and to demonstrate the urgent need to expose the nation and the nation’s children to the valuable store available to them. For this purpose, the Conference Committee has assembled a dynamic group of writers, both renowned and budding, who are making their mark on the literary landscape and whose works should be made available to students from primary to tertiary levels of education. An author’s calendar is being constructed and will be made available online. The conference makes room for critical responses and also has specially built in important commentary from students and teachers and from officers attached to the Ministry of Education and others who have worked long in the field of educating the educators. See More | Register THE UNIVERSITY OF THE WEST INDIES ST. AUGUSTINE CAMPUS TRINIDAD & TOBAGO WEST INDIES International Literary Conference CALENDAR OF EVENTS: MONDAY 21ST SEPTEMBER, 2020 INTRODUCTION TO THE LITERARY LANDSCAPE OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Day Chair: Dr. J. Vijay Maharaj 8:00am - 8:45 am OPENING THE FRONTIERS Moderator: Dr. J. Vijay Maharaj Welcome, HOD DLCCS: Professor Paula Morgan Greetings by the Principal UWI STA: The Humanities in the 21st Century- Professor Brian Copeland Remarks from the Chairman, Friends of Mr Biswas The Conference: Structure and Purpose – Professor Kenneth Ramchand Feature Address by the Minister of Education: Dr the Honourable Nyan Gadsby-Dolly 8:45am – 9:45am THE HEART OF THE MATTER Moderator: Professor Kenneth Ramchand Presentation of the Annotated Bibliography: Ms. -

Editorial Literacy:Reconsidering Literary Editing As Critical Engagement in Writing Support

St. John's University St. John's Scholar Theses and Dissertations 2020 Editorial Literacy:Reconsidering Literary Editing as Critical Engagement in Writing Support Anna Cairney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Creative Writing Commons EDITORIAL LITERACY: RECONSIDERING LITERARY EDITING AS CRITICAL ENGAGEMENT IN WRITING SUPPORT A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY to the faculty in the department of ENGLISH of ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES at ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY New York by Anna Cairney Date Submitted: 1/27/2020 Date Approved: 1/27/2020 __________________________________ __________________________________ Anna Cairney Derek Owens, D.A. © Copyright by Anna Cairney 2020 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT EDITORIAL LITERACY: RECONSIDERING LITERARY EDITING AS CRITICAL ENGAGEMENT IN WRITING SUPPORT Anna Cairney Editing is usually perceived in the pejorative within in the literature of composition studies generally, and specifically in writing center studies. Regardless if the Writing Center serves mostly undergraduates or graduates, the word “edit” has largely evolved to a narrow definition of copyediting or textual cleanup done by the author at the end of the writing process. Inversely, in trade publishing, editors and agents work with writers at multiple stages of production, providing editorial feedback in the form of reader’s reports and letters. Editing is a rich, intellectual skill of critically engaging with another’s text. What are the implications of differing literacies of editing for two fields dedicated to writing production? This dissertation examines the editorial practices of three leading 20th century editors: Maxwell Perkins, Katharine White, and Ursula Nordstrom. -

Swanzy, Henry Valentine Leonard (1915–2004) Gabriella Ramsden Published Online: 12 November 2020

Swanzy, Henry Valentine Leonard (1915–2004) Gabriella Ramsden https://doi.org/10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.57680 Published online: 12 November 2020 Swanzy, Henry Valentine Leonard (1915–2004), radio producer, was born on 14 June 1915 at Glanmire Rectory, Glanmire, co. Cork, Ireland, the eldest son of the Revd Samuel Leonard Swanzy (1875–1920), rector of Glanmire, and his wife, Joan Frances, née Glenny (1888–1975). His brothers John and Leonard were born in 1917 and 1920 respectively, the latter after the death of their father. The family subsequently moved to England. Henry attended Wellington College and won a scholarship to New College, Oxford, achieving first-class honours in modern history. In order to pursue a career in the civil service, he learned French and German, and he travelled around Europe. After four years in the Colonial Office, where he progressed to assistant principal, he joined the BBC in 1941. On 12 March 1946 Swanzy married Eileen Lucy (Tirzah) Ravilious, née Garwood (1908–1951), daughter of Frederick Scott Garwood, an officer in the Royal Engineers, and widow of the painter, designer, book engraver, and war artist Eric Ravilious. Following her death in March 1951, on 22 July 1952 Swanzy married Henrietta Theodora Van Eeghan (1924–2006), with whom he had two sons and a daughter. Swanzy began his career as a producer for the general overseas service, but it was his involvement in the radio programme Caribbean Voices between 1946 and 1954 that he was best known for. He encouraged writers from the Caribbean to contribute stories and poems. This fostered the careers of many notable West Indian writers, two of whom, Derek Walcott and V. -

V.S. Naipaul: from Gadfly to Obsessive

V.S. Naipaul: From Gadfly to Obsessive Mohamed Bakari* All the examples Naipaul gives, all the people he speaks to tend to align themselves under the Islam versus the West opposition he is determined to find everywhere. It is all tiresome and repetitious. Edward W.Said The Man and the Prize : The announcement of the 2001 Nobel Laureate for Literature in October that year elicited the kind of reaction that was predictable, given the reputation and the choice, that of Sir Vidhiadar Surajparasad Naipaul. Of Indian ancestry, V.S. Naipaul is a grandchild of Hindu Brahmins who found their way to the Caribbean island of Trinidad as indentured labourers to escape the grinding poverty of Utterpradesh. Naipaul’s was just one of a stream of families that were encouraged to migrate to the West Indies from the former British colonies of India and Chinese enclaves in Mainland China. Slavery had been abolished in the British Empire in 1832 and the former African slaves were no longer available to the sugarcane plantations and labour had to be sought from somewhere. In their natural ingenuity the British devised the new institution of indentured labour, which was really a new euphemism for a new form of servitude. Whereas the slaves were forcibly repatriated against their will, the new indentured labourers had the carrot of landownership dangled in front of them, to lure them to places they had no idea of. The new immigrants added a new dimension to an already complex racial situation, by adding the Asian layer to the Carib, European and African admixtures created by Alternatives: Turkish Journal of International Relations, Vol.2, No.3&4, Fall&Winter 2003 243 waves of migration. -

Kingsley Amis Under Tlle Much Good Debate And, 1 Hope, Saving of Money

Foreword Centre for Policy Studies by Hugh Thomas London 1979 Rfr Kingslry Amis has been delighting readers with his wit and stylc for twenty-five years. 0 Lucky Jim! How we remember him! Ilowever, Mr Amis’s long string of accomplished novels is only one sick., if the most important part, of his literary achievement. There is his poetry. There is his criticism. Now here are his political reconimendations. These are, to he sure, First published 1979 recoinmendations for a policy towards the arts. But, by Centre for Policy Studies nevertheless, they are political if only because they deal firmly 8 \Vilfretl Street and squarely with the argument that the arts should be London SW 1 “politicised”. A horrible word, it is true, but an appropriate Prinbd by S S IV Ltd one for a rotten idea. Mr Amis, too, shows that he could he an 39/21 Great Portland Street inspiring politician. What is his policy? A heavy investment in London Wl poets? Subsidy for exporting novelists? Tax-free dachas for 0 I<ingsley Amis needy critics? Compulsory attendance at courses on cinema ISBN 0 905880 23 4 and TV drama for those writers who have neglected these important nrw forms? Not a bit of it. But Rfr Amis’s plan is for us to have no arts policy. This is a very skilful plan though he would he the first to agree that it is a difficult one to introduce and carry through in a nation much used to busy bodies. At the end of his pamphlet -aversion of a speech delivered at the Centre’s fringe meeting at the 1979 Conservative Conference at Blackpool - Mr Amis alloivs his Publication by tile Centre for Policy Studies does not imply acceptance of attention to wander -orat least so I believe - and suggests aiitlion’conciosioas or prescriptions.