Overdraft Protection a Guide for Bankers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

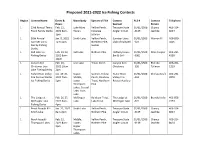

Proposed 2021-2022 Ice Fishing Contests

Proposed 2021-2022 Ice Fishing Contests Region Contest Name Dates & Waterbody Species of Fish Contest ALS # Contact Telephone Hours Sponsor Person 1 23rd Annual Teena Feb. 12, Lake Mary Yellow Perch, Treasure State 01/01/1500 Chancy 406-314- Frank Family Derby 2022 6am- Ronan Kokanee Angler Circuit -3139 Jeschke 8024 1pm Salmon 1 50th Annual Jan. 8, 2022 Smith Lake Yellow Perch, Sunriser Lions 01/01/1500 Warren Illi 406-890- Sunriser Lions 7am-1pm Northern Pike, Club of Kalispell -323 0205 Family Fishing Sucker Derby 1 Bull Lake Ice Feb. 19-20, Bull Lake Nothern Pike Halfway House 01/01/1500 Dave Cooper 406-295- Fishing Derby 2022 6am- Bar & Grill -3061 4358 10pm 1 Canyon Kid Feb. 26, Lion Lake Trout, Perch Canyon Kids 01/01/1500 Rhonda 406-261- Christmas Lion 2022 10am- Christmas -326 Tallman 1219 Lake Fishing Derby 2pm 1 Fisher River Valley Jan. 29-30, Upper, Salmon, Yellow Fisher River 01/01/1500 Chelsea Kraft 406-291- Fire Rescue Winter 2022 7am- Middle, Perch, Rainbow Valley Fire -324 2870 Ice Fishing Derby 5pm Lower Trout, Northern Rescue Auxilary Thompson Pike Lakes, Crystal Lake, Loon Lake 1 The Lodge at Feb. 26-27, McGregor Rainbow Trout, The Lodge at 01/01/1500 Brandy Kiefer 406-858- McGregor Lake 2022 6am- Lake Lake Trout McGregor Lake -322 2253 Fishing Derby 4pm 1 Perch Assault #2- Jan. 22, 2022 Smith Lake Yellow Perch, Treasure State 01/01/1500 Chancy 406-314- Smith Lake 8am-2pm Nothern Pike Angler Circuit -3139 Jeschke 8024 1 Perch Assault- Feb. -

Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat

ruses science for a changing world Prepared in cooperation with the Alaska Energy Authority u Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4191 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photograph: Ice pedestals at Bradley River near Tidewater transect, February 28, 1995. Effects of Ice Formation on Hydrology and Water Quality in the Lower Bradley River, Alaska Implications for Salmon Incubation Habitat by Ronald L. Rickman U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4191 Prepared in cooperation with the ALASKA ENERGY AUTHORITY Anchorage, Alaska 1998 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas J. Casadevall, Acting Director Use of trade names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information: Copies of this report may be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 4230 University Drive, Suite 201 Box 25286 Anchorage, AK 99508-4664 Denver, CO 80225-0286 http://www-water-ak.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................... 1 Location of Study Area.................................................. 1 Bradley Lake Hydroelectric Project ....................................... -

BIOSPHERE SMART AGRICULTURE in a TRUE COST ECONOMY TRUE COST of FOOD and AGRICULTURE INDEX L Amount of Soil Lost Worldwide, According to the U.N

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE WORLD BANK BIOSPHERE SMART AGRICULTURE IN A TRUE COST ECONOMY TRUE COST OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE INDEX l Amount of soil lost worldwide, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): 75 billion tons l Approximate annual economic cost of that lost soil: US $ 400 billion, or about US $ 70 per person, per year (FAO) l Approximate percentage of the world’s population that is now overweight or obese, according to the McKinsey Global Institute: 30 percent l Estimated global economic impact related to the health costs of that nutritional crisis: US$2 trillion annually, or 2.8 percent of global GDP l Percentage of the Earth’s freshwater resources now diverted for agriculture: 70 percent l Number of major underground water reservoirs designated as beyond “sustainability tipping points” according to researchers at the University of California at Irvine: 21 of 37 l Number of impacted marine and riverine ecosystems known as Dead Zones due to excess nutrients greatly affected by agriculutral production: 400 l Probability that the planet will warm by 4 degrees Celsius (7.2 degrees Fahrenheit) by the end of the century according to the World Bank: at least 40 percent l Estimated amount that crop yields are projected to decrease if temperatures rise above 2 degress C: 15 to 20 percent (WB) l Percentage of people in low-income countries who work in agriculture: 60% (WB) l Estimated health costs of global pesticide applications, a problem barely studied: US$1.1 billion per year. (Pesticide Action Network) l Estimated amount of global food production classified as food waste: 30 to 40 percent l Estimated global costs of food waste when environmental and social impacts are included according to Food Wastage Footprint: US$2.6 trillion per year 2 POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE WORLD BANK - zxzxzxzxzxzxzxzxzxzxzx BIOSPHERE SMART AGRICULTURE IN A TRUE COST ECONOMY September 2015, Washington DC, Our findings and recommendations are relatively simple, yet profound. -

CHAPTER 13 Groundwater Collective Management Systems: the United States Experience

13-Smith.qxd 02-10-2002 19:59 Pagina 257 CHAPTER 13 Groundwater collective management systems: the United States experience Z.A. Smith Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT: Groundwater management in the USA is diverse and decentralized making generaliza- tions sometimes difficult. In many areas groundwater is managed well under permit systems that pre- vent wasteful overuse and allow planned development. In other areas individuals are free to pump water with few restrictions and sometimes with wasteful consequences. This chapter provides an overview of collective groundwater management systems used in the USA by summarizing the types of systems in place and the advantages and disadvantages of each system. It concludes with an exam- ination of what can be learned from the groundwater management experience in the USA and sug- gestions for the development of future groundwater management systems. 1 INTRODUCTION others very little groundwater is used (Table 1 gives a state-by-state breakdown of groundwater The rules governing groundwater use in much of use). the USA and the world bring to mind the state- ment in Plato’s Republic “I declare justice is 1.2 Role of the national government nothing but the advantage of the stronger”. Is this how things should be? In much of the USA To examine in a comprehensive manner the and the rest of the world this is how it is. In this experience of managing groundwater in the chapter we will examine the experience of the USA is a daunting task. The first thing that one USA in the collective cooperation and manage- must understand is that there is no national ment of groundwater resources. -

“Mining” Water Ice on Mars an Assessment of ISRU Options in Support of Future Human Missions

National Aeronautics and Space Administration “Mining” Water Ice on Mars An Assessment of ISRU Options in Support of Future Human Missions Stephen Hoffman, Alida Andrews, Kevin Watts July 2016 Agenda • Introduction • What kind of water ice are we talking about • Options for accessing the water ice • Drilling Options • “Mining” Options • EMC scenario and requirements • Recommendations and future work Acknowledgement • The authors of this report learned much during the process of researching the technologies and operations associated with drilling into icy deposits and extract water from those deposits. We would like to acknowledge the support and advice provided by the following individuals and their organizations: – Brian Glass, PhD, NASA Ames Research Center – Robert Haehnel, PhD, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory – Patrick Haggerty, National Science Foundation/Geosciences/Polar Programs – Jennifer Mercer, PhD, National Science Foundation/Geosciences/Polar Programs – Frank Rack, PhD, University of Nebraska-Lincoln – Jason Weale, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers/Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory Mining Water Ice on Mars INTRODUCTION Background • Addendum to M-WIP study, addressing one of the areas not fully covered in this report: accessing and mining water ice if it is present in certain glacier-like forms – The M-WIP report is available at http://mepag.nasa.gov/reports.cfm • The First Landing Site/Exploration Zone Workshop for Human Missions to Mars (October 2015) set the target -

Overdrafting Toward Disaster: a Call for Local Groundwater Management Reform in California’S Central Valley

Comments Overdrafting Toward Disaster: A Call for Local Groundwater Management Reform in California’s Central Valley By PHILIP LAIRD* Introduction MY GRANDFATHER has been a farmer all of his life. He has grown raisins in Selma, California for over seventy years. Like most crops, raisins need good soil, sunshine, and a steady flow of water. Without any one of these elements, the vines will die, and the crop will be a loss. Water, as one can imagine, ends up being the most problematic resource. There are no rivers or canals that run by my grandfather’s property. Thus in order to nourish his vineyard and make the vines grow, he has to pump groundwater. My grandfather first began using his pump in the 1930s. At that time, the well he used only had to extend down eighteen feet to reach the water table and provide suffi- cient water to his ranch. As the years went by though, the water table dropped, and he had to spend more and more money digging deeper wells and pumping from greater depths. Today, in order to reach the water table, my grandfather’s well is ninety feet deep. This story is not unique to my grandfather. The water table throughout California is dropping at an alarming rate, and thus far, efforts to seriously curb this depletion are minimal at best. Currently, groundwater in California provides approximately 30% of the state’s * J.D. Candidate, University of San Francisco School of Law (2013); B.A. English Language Literature, University of California, Santa Cruz (2010). The author would like to thank Professor Richard Roos-Collins for his patience, wisdom, and guidance in overseeing the development of this Comment. -

Questions About Texas Groundwater Conservation Districts

Questions about Texas Groundwater Conservation Districts Bruce Lesikar Associate Professor and Extension Agricultural Engineering Specialist Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering Ronald Kaiser Professor, Institute of Renewable Natural Resources and Department of Recreation, Parks and Tourism Science Valeen Silvy Program Coordinator, Texas Water Resources Institute All of The Texas A&M University System Contributing editors Kelly Mills, Texas Commission on Environmental Quality Harvey Everheart, Texas Alliance of Groundwater Districts Trey Powers, Texas Department of Agriculture Cindy Loeffler, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Richard Preston, Texas Water Development Board Disclaimer The purpose of this publication is to present useful information about Texas groundwater law and groundwater conservation dis- tricts. It is not intended to furnish specific legal advice, or to ren- der a legal opinion. If you are seeking specific legal advice, please consult with an attorney. Contents 1 Introduction 1 Water use in Texas 2 Groundwater 2 Surface water 5 Movement of groundwater in aquifers 5 Are all Texas aquifers alike? 5 How much water do Texas aquifers provide each year? 6 How does water get into an aquifer? How is an aquifer replenished? 7 Does water discharge from an aquifer naturally? 7 If aquifers recharge, why is there a problem with pumping? 7 What is a cone of depression? 7 What is well interference? 8 What is aquifer overdrafting or mining? 9 Texas water law 9 What rights do landowners have to use groundwater? 9 -

Systems Approach to Management of Water Resources—Toward Performance Based Water Resources Engineering

water Article Systems Approach to Management of Water Resources—Toward Performance Based Water Resources Engineering Slobodan P. Simonovic Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON N6A 5B9, Canada; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-519-661-4075 Received: 29 March 2020; Accepted: 20 April 2020; Published: 24 April 2020 Abstract: Global change, that results from population growth, global warming and land use change (especially rapid urbanization), is directly affecting the complexity of water resources management problems and the uncertainty to which they are exposed. Both, the complexity and the uncertainty, are the result of dynamic interactions between multiple system elements within three major systems: (i) the physical environment; (ii) the social environment; and (iii) the constructed infrastructure environment including pipes, roads, bridges, buildings, and other components. Recent trends in dealing with complex water resources systems include consideration of the whole region being affected, explicit incorporation of all costs and benefits, development of a large number of alternative solutions, and the active (early) involvement of all stakeholders in the decision-making. Systems approaches based on simulation, optimization, and multi-objective analyses, in deterministic, stochastic and fuzzy forms, have demonstrated in the last half of last century, a great success in supporting effective water resources management. This paper explores the future opportunities that will utilize advancements in systems theory that might transform management of water resources on a broader scale. The paper presents performance-based water resources engineering as a methodological framework to extend the role of the systems approach in improved sustainable water resources management under changing conditions (with special consideration given to rapid climate destabilization). -

Ecology: Biodiversity and Natural Resources Part 1

CK-12 FOUNDATION Ecology: Biodiversity and Natural Resources Part 1 Akre CK-12 Foundation is a non-profit organization with a mission to reduce the cost of textbook materials for the K-12 market both in the U.S. and worldwide. Using an open-content, web-based collaborative model termed the “FlexBook,” CK-12 intends to pioneer the generation and distribution of high-quality educational content that will serve both as core text as well as provide an adaptive environment for learning. Copyright © 2010 CK-12 Foundation, www.ck12.org Except as otherwise noted, all CK-12 Content (including CK-12 Curriculum Material) is made available to Users in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution/Non-Commercial/Share Alike 3.0 Un- ported (CC-by-NC-SA) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/), as amended and updated by Creative Commons from time to time (the “CC License”), which is incorporated herein by this reference. Specific details can be found at http://about.ck12.org/terms. Printed: October 11, 2010 Author Barbara Akre Contributor Jean Battinieri i www.ck12.org Contents 1 Ecology: Biodiversity and Natural Resources Part 1 1 1.1 Lesson 18.1: The Biodiversity Crisis ............................... 1 1.2 Lesson 18.2: Natural Resources .................................. 32 2 Ecology: Biodiversity and Natural Resources Part I 49 2.1 Chapter 18: Ecology and Human Actions ............................ 49 2.2 Lesson 18.1: The Biodiversity Crisis ............................... 49 2.3 Lesson 18.2: Natural Resources .................................. 53 www.ck12.org ii Chapter 1 Ecology: Biodiversity and Natural Resources Part 1 1.1 Lesson 18.1: The Biodiversity Crisis Lesson Objectives • Compare humans to other species in terms of resource needs and use, and ecosystem service benefits and effects. -

Landcare Degradation

Land degradation WHAT IS LAND DEGRADATION? Land degradation is a broad term that can be applied differently across a wide range of scenarios. It is a process in which the value of the biophysical environment is affected by a combination of human-induced processes acting upon the land. It is the reduction in the capacity of the land to provide ecosystem goods and services and assure its functions over a period of time for the beneficiaries of this. Increased population pressures and excessive human expansion into drylands during long wet periods leave an increasing number of people stranded there during dry periods. CAUSES OF LAND DEGRADATION: Land degradation is a global problem, largely related to agricultural use. The major causes include: Land clearance, such as clearcut- ting and deforestation; Agricultural depletion of soil nutrients through poor farming practices; Livestock farming that includes over- grazing and overdrafting; Inappropriate irrigation and overdrafting; Monoculture that destabilises the local ecosystem; and Urban sprawl and commercial development. IMPACT: There are four main ways of looking at land degradation and its impact on the environment around it: A temporary or permanent decline in the productive capacity of the land: This can be seen through a loss of biomass, a loss of actual or potential productivity, or a loss or change in vegetative cover and soil nutrients; Action in the land’s capacity to provide resources for human livelihoods: This can be measured from a baseline of previous land use; Loss of biodiversity: A loss of range of species or ecosystem complexity as a decline in the environmental quality; and Shifting ecological risk: Increased vulnerability of the environment or people to destruction or crisis. -

The Modelling of Freezing Process in Saturated Soil Based on the Thermal-Hydro-Mechanical Multi-Physics Field Coupling Theory

water Article The Modelling of Freezing Process in Saturated Soil Based on the Thermal-Hydro-Mechanical Multi-Physics Field Coupling Theory Dawei Lei 1,2, Yugui Yang 1,2,* , Chengzheng Cai 1,2, Yong Chen 3 and Songhe Wang 4 1 State Key Laboratory for Geomechanics and Deep Underground Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou 221008, China; [email protected] (D.L.); [email protected] (C.C.) 2 School of Mechanics and Civil Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou 221116, China 3 State Key Laboratory of Coal Resource and Safe Mining, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou 221116, China; [email protected] 4 Institute of Geotechnical Engineering, Xi’an University of Technology, Xi’an 710048, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 September 2020; Accepted: 22 September 2020; Published: 25 September 2020 Abstract: The freezing process of saturated soil is studied under the condition of water replenishment. The process of soil freezing was simulated based on the theory of the energy and mass conservation equations and the equation of mechanical equilibrium. The accuracy of the model was verified by comparison with the experimental results of soil freezing. One-side freezing of a saturated 10-cm-high soil column in an open system with different parameters was simulated, and the effects of the initial void ratio, hydraulic conductivity, and thermal conductivity of soil particles on soil frost heave, freezing depth, and ice lenses distribution during soil freezing were explored. During the freezing process, water migrates from the warm end to the frozen fringe under the actions of the temperature gradient and pore pressure. -

Chapter 7 Seasonal Snow Cover, Ice and Permafrost

I Chapter 7 Seasonal snow cover, ice and permafrost Co-Chairmen: R.B. Street, Canada P.I. Melnikov, USSR Expert contributors: D. Riseborough (Canada); O. Anisimov (USSR); Cheng Guodong (China); V.J. Lunardini (USA); M. Gavrilova (USSR); E.A. Köster (The Netherlands); R.M. Koerner (Canada); M.F. Meier (USA); M. Smith (Canada); H. Baker (Canada); N.A. Grave (USSR); CM. Clapperton (UK); M. Brugman (Canada); S.M. Hodge (USA); L. Menchaca (Mexico); A.S. Judge (Canada); P.G. Quilty (Australia); R.Hansson (Norway); J.A. Heginbottom (Canada); H. Keys (New Zealand); D.A. Etkin (Canada); F.E. Nelson (USA); D.M. Barnett (Canada); B. Fitzharris (New Zealand); I.M. Whillans (USA); A.A. Velichko (USSR); R. Haugen (USA); F. Sayles (USA); Contents 1 Introduction 7-1 2 Environmental impacts 7-2 2.1 Seasonal snow cover 7-2 2.2 Ice sheets and glaciers 7-4 2.3 Permafrost 7-7 2.3.1 Nature, extent and stability of permafrost 7-7 2.3.2 Responses of permafrost to climatic changes 7-10 2.3.2.1 Changes in permafrost distribution 7-12 2.3.2.2 Implications of permafrost degradation 7-14 2.3.3 Gas hydrates and methane 7-15 2.4 Seasonally frozen ground 7-16 3 Socioeconomic consequences 7-16 3.1 Seasonal snow cover 7-16 3.2 Glaciers and ice sheets 7-17 3.3 Permafrost 7-18 3.4 Seasonally frozen ground 7-22 4 Future deliberations 7-22 Tables Table 7.1 Relative extent of terrestrial areas of seasonal snow cover, ice and permafrost (after Washburn, 1980a and Rott, 1983) 7-2 Table 7.2 Characteristics of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets (based on Oerlemans and van der Veen, 1984) 7-5 Table 7.3 Effect of terrestrial ice sheets on sea-level, adapted from Workshop on Glaciers, Ice Sheets and Sea Level: Effect of a COylnduced Climatic Change.