Framework Knitting in Nottinghamshire – from Invention to Dissension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palmetto Tatters Guild Glossary of Tatting Terms (Not All Inclusive!)

Palmetto Tatters Guild Glossary of Tatting Terms (not all inclusive!) Tat Days Written * or or To denote repeating lines of a pattern. Example: Rep directions or # or § from * 7 times & ( ) Eg. R: 5 + 5 – 5 – 5 (last P of prev R). Modern B Bead (Also see other bead notation below) notation BTS Bare Thread Space B or +B Put bead on picot before joining BBB B or BBB|B Three beads on knotting thread, and one bead on core thread Ch Chain ^ Construction picot or very small picot CTM Continuous Thread Method D Dimple: i.e. 1st Half Double Stitch X4, 2nd Half Double Stitch X4 dds or { } daisy double stitch DNRW DO NOT Reverse Work DS Double Stitch DP Down Picot: 2 of 1st HS, P, 2 of 2nd HS DPB Down Picot with a Bead: 2 of 1st HS, B, 2 of 2nd HS HMSR Half Moon Split Ring: Fold the second half of the Split Ring inward before closing so that the second side and first side arch in the same direction HR Half Ring: A ring which is only partially closed, so it looks like half of a ring 1st HS First Half of Double Stitch 2nd HS Second Half of Double Stitch JK Josephine Knot (Ring made of only the 1st Half of Double Stitch OR only the 2nd Half of Double Stitch) LJ or Sh+ or SLJ Lock Join or Shuttle join or Shuttle Lock Join LPPCh Last Picot of Previous Chain LPPR Last Picot of Previous Ring LS Lock Stitch: First Half of DS is NOT flipped, Second Half is flipped, as usual LCh Make a series of Lock Stitches to form a Lock Chain MP or FP Mock Picot or False Picot MR Maltese Ring Pearl Ch Chain made with pearl tatting technique (picots on both sides of the chain, made using three threads) P or - Picot Page 1 of 4 PLJ or ‘PULLED LOOP’ join or ‘PULLED LOCK’ join since it is actually a lock join made after placing thread under a finished ring and pulling this thread through a picot. -

Explores Form Possibilities in Knitwear Through Material Interactions

Contract knit Explores form possibilities in knitwear through material interactions Bachelor in Fine Arts; Fashion Design Sofie Larsson May 2015 2015.3.04 Index Abstract 1 Look book 2 Introduction to the field 18 Abstract Knitting 18 Intarsia knit 18 The focus of this degree work is on material interaction within the field of knitwear. Material combinations are often seen in fashion as a decorative effect to add shine, transparency Motive and idea discussion 19 or blocks of colour. The materials are put together as one flat material. Material interaction in fashion 19 Form in knitwear 20 This work embraces the different qualities and explores the possibilities to use material interac- tion as a way of creating form on the body. Aim 21 To achieve this, material experiments have been made to find combinations that had a big impact on each other. The materials that were found to be most suitable for this were the combination of Design method and design of experiments 22 metal and lycra yarn. This combination showed contrast in both volume and in density. The result is a collection of seven examples that is based from square knitted pieces where the Development 24 interaction changes the form of the material and the garment. Material development 24 Shape development 32 Creating form from material combination could lead to a new method of creating garments with larger form possibilities than is seen today in ready to wear knitted garments. Colour 40 Garment development 48 Lineup development 52 Result 54 Materials 55 Presentation of collection 56 Discussion & Reflection 86 References 88 Figure references 89 Appendix 1 - Critique Keywords Knitting, knitwear, fashion design, material interaction, form 1 Look book Model/ Sofia K. -

NEEDLE LACES Battenberg, Point & Reticella Including Princess Lace 3Rd Edition

NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INCLUDING PRINCESS LACE 3RD EDITION EDITED BY JULES & KAETHE KLIOT LACIS PUBLICATIONS BERKELEY, CA 94703 PREFACE The great and increasing interest felt throughout the country in the subject of LACE MAKING has led to the preparation of the present work. The Editor has drawn freely from all sources of information, and has availed himself of the suggestions of the best lace-makers. The object of this little volume is to afford plain, practical directions by means of which any lady may become possessed of beautiful specimens of Modern Lace Work by a very slight expenditure of time and patience. The moderate cost of materials and the beauty and value of the articles produced are destined to confer on lace making a lasting popularity. from “MANUAL FOR LACE MAKING” 1878 NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INLUDING PRINCESS LACE True Battenberg lace can be distinguished from the later laces CONTENTS by the buttonholed bars, also called Raleigh bars. The other contemporary forms of tape lace use the Sorrento or twisted thread bar as the connecting element. Renaissance Lace is INTRODUCTION 3 the most common name used to refer to tape lace using these BATTENBERG AND POINT LACE 6 simpler stitches. Stitches 7 Designs 38 The earliest product of machine made lace was tulle or the PRINCESS LACE 44 RETICELLA LACE 46 net which was incorporated in both the appliqued hand BATTENBERG LACE PATTERNS 54 made laces and later the elaborate Leavers laces. It would not be long before the narrow tapes, in fancier versions, would be combined with this tulle to create a popular form INTRODUCTION of tape lace, Princess Lace, which became and remains the present incarnation of Belgian Lace, combining machine This book is a republication of portions of several manuals made tapes and motifs, hand applied to machine made tulle printed between 1878 and 1938 dealing with varieties of and embellished with net embroidery. -

Framework Knitting and the Hosiery Trade

BELPER TOWN CENTRE FRAMEWORK KNITTING AND THE HOSIERY TRADE DERWENT VALLEY VISITOR CENTRE The partnership between Brettle and Ward was dissolved and George Brettles built his own factory Framework Knitting in 1834. These two firms were of considerable size. They made silk stockings for George III, George IV and Queen Victoria. and the Ward’s ceased trading in the 1930’s and Brettles in 1987. Many smaller hosiery firms provided work for local people and these were scattered around the Hosiery trade town. All these factories have closed except for Aristoc which now operates across the road in the West Mill. Circular knitting slowly superseded flatbed knitting, as it was more efficient. Today all hosiery is made this way. For more information visit Strutt’s North Mill, The Derwent Valley Visitor Centre Bridgefoot, Belper, Derbyshire, DE56 1YD Tel: 01773 880474 / 0845 5214347 BELPER NORTH MILL Email: [email protected] www.belpernorthmill.org.uk Local Interest Leaflet The existing part of Brettles factory, now De Bradelei Stores Leaflet design by Mayers Design Ltd · www.mayers-design.co.uk Number 3 Framework knitters earned a poor living, usually their on by hand. After a brief partnership with two Derby frames were hired from the hosier who was supplying hosiers, Jedediah formed a successful partnership with the yarn and selling the stockings. The framework Samuel Need, an older, experienced hosier from knitter would have to pay the rent for the frame Nottingham who was able to finance the venture. This even when there was no work. The machines were made Jedediah Strutt’s first fortune. -

Bobbin Lace You Need a Pattern Known As a Pricking

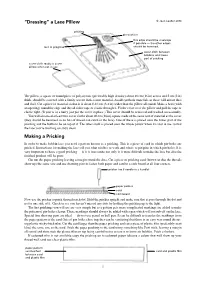

“Dressing” a Lace Pillow © Jean Leader 2014 pricking pin-cushion this edge should be a selvage if possible — the other edges lace in progress should be hemmed. cover cloth between bobbins and lower part of pricking cover cloth ready to cover pillow when not in use The pillow, a square or round piece of polystyrene (preferably high density) about 40 cm (16 in) across and 5 cm (2 in) thick, should be covered with a firmly woven dark cotton material. Avoid synthetic materials as these will attract dust and fluff. Cut a piece of material so that it is about 8-10 cm (3-4 in) wider than the pillow all round. Make a hem (with an opening) round the edge and thread either tape or elastic through it. Fit the cover over the pillow and pull the tape or elastic tight. (If you’re in a hurry just pin the cover in place.) This cover should be removed and washed occasionally. You will also need at least two cover cloths about 40 cm (16 in) square made of the same sort of material as the cover (they should be hemmed so no bits of thread can catch in the lace). One of these is placed over the lower part of the pricking and the bobbins lie on top of it. The other cloth is placed over the whole pillow when it is not in use so that the lace you’re working on stays clean. Making a Pricking In order to make bobbin lace you need a pattern known as a pricking. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif. -

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Text copyright © Jeremy Farrell, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name held at The Museum of Costume and Textiles, Nottingham on 21st February 2008. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audiences. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750 -1950 Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 Front cover image: Detail of a triangular shawl of white cotton Pusher lace made by William Vickers of Nottingham, 1870. The Pusher machine cannot put in the outline which has to be put in by hand or by embroidering machine. The outline here was put in by hand by a woman in Youlgreave, Derbyshire. (NCM 1912-13 © Nottingham City Museums) 2 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Contents Page 1. List of illustrations 1 2. Introduction 3 3. The main types of hand and machine lace 5 4. -

This Is Why Iknit

INSIDE THIS ISSUE: THIS IS WHY I KNIT Meet Your Guild Members 2 2 Pattern Review of the cost. No mat- can sum up my On the Web 3 ter how much I ex- answer just with this plain that it isn’t photo. This is (was) a blan- History of Guilds 4 about the price, non- ket I knit four years ago for knitters just don’t a pregnant friend of my Our 30th Year 5 get it. daughter. The blanket is the most favorite item the Product Review 7 four year old boy has. He A lot of knitters have doesn’t go anywhere with- 7 an item that they Coming Attractions out his blanket. The always have on the mother just sent me the Improve your Knitting 8 needles. With many photo as a thank you for of my friends there is 9 making such a cherished Book Review always a pair of item. This is why I knit and socks or a preemie this is why I choose to Recipe 10 hat in a project bag keep knitting baby blan- ready to knit when 10 From the Editor there are a few min- kets. Retreats 11 utes of free time. Christine Hall With me, my item of choice I have often been told by 12 is a baby blanket. I hear DKG Retreat non-knitters that it makes Do you have a story about the argument that baby no sense to knit an item what motivates you to Guild Information 14 blankets are a lot of yarn because I can purchase it knit? Please share it with and take a lot of time. -

A History of Woolcombing, Yarn Spinning & Framework Knitting In

A HISTORY OF WOOLCOMBING, YARN SPINNING & FRAMEWORK KNITTING IN LOCAL VILLAGES BY SAMUEL T STEWART – MAY 2020 1 EXTRACTS FROM THE REPORTS IN PART 3 2 CONTENTS PART 1 – PAGE 4 A SYNOPSIS OF THE WOOL COMBING INDUSTRY BASED MAINLY ON RESEARCH CARRIED OUT BY THE AUTHOR ON THE SHERWINS’ OF COLEORTON PART 2 – PAGE 7 THE FRAMEWORK KNITTING INDUSTRY PART 3 – PAGE 13 REPORTS FROM THE COMMISSIONERS’ ON FRAMEWORK KNITTERS IN LEICESTERSHIRE, CARRIED OUT BY ORDER OF THE HOUSE OF LORDS IN 1845 - Reports from Belton (page 14) - Reports from Whitwick (page 17) - Report from Osgathorpe (page 32) - Reports from Thringstone (page 33) FURTHER RECOMMENDED READING – FRAMEWORK KNITTING BY MARILYN PALMER SHIRE LIBRARY © Samuel T Stewart – May 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise without first seeking the written permission of the author 3 PART 1 A SYNOPSIS OF THE WOOL COMBING INDUSTRY BASED ON RESEARCH CARRIED OUT ON THE SHERWINS’ OF COLEORTON The author has written a book entitled “The Coleorton Sherwins’ 1739-1887” from which certain parts of the following are taken. This is on the author’s website as a free to down load and read pdf doc. In order to understand the Framework Knitting industry which features later, it is necessary to first understand something about the production of the raw material (yarns) used in the knitting process. It should be noted that the word “Hosier” is a general description for a manufacturer involved in the hosiery industry. -

Textile Design: a Suggested Program Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME CI 003 141 ED 102 409 95 Program Guide.Fashion TITLE Textile Design: A Suggested Industry Series No. 3. Fashion Inst. of Tech.,New York, N.T. INSTITUTION Education SPONS AGENCY Bureau of Adult,Vocational, and Technictl (DREW /OE), Washington,D.C. PUB DATE 73 in Fashion Industry NOTE 121p.; For other documents Series, see CB 003139-142 and CB 003 621 Printing AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents,U.S. Government Office, Washington, D.C.20402 EDRS PRICE NP -$0.76 HC-$5.70 PLUS POSTAGE Behavioral Objectives; DESCRIPTORS Adult, Vocational Education; Career Ladders; *CurriculumGuides; *Design; Design Crafts; EducationalEquipment; Employment Opportunities; InstructionalMaterials; *Job Training; Needle Trades;*Occupational Rome Economics; OccupationalInformation; Program Development; ResourceGuides; Resource Units; Secondary Education;Skill Development;*Textiles Instruction IDENTIFIERS *Fashion Industry ABSTRACT The textile designguide is the third of aseries of resource guidesencompassing the various five interrelated program guide is disensions of the fashionindustry. The job-preparatory conceived to provide youthand adults withintensive preparation for and also with careeradvancement initial entry esploysent jobs within the textile opportunities withinspecific categories of provides an overviewof the textiledesign field, industry. The guide required of workers. It occupational opportunities,and cospetencies contains outlines of areasof instruction whichinclude objectives to suggestions for learning be achieved,teaching -

Diversity.Pdf

Diversity the company Groz-Beckert www.groz-beckert.com Contents The company 4 Traditional 6 Together 8 Responsible 10 Integrative 12 Sustainable 14 Products and services 16 Knitting 18 Weaving 19 Felting 20 Tufting 21 Carding 22 Sewing 23 Other products 24 Other services 25 Research and development 26 The Technology and Development Center (TEZ) 28 Facts and figures at a glance Groz-Beckert produces industrial machine needles, precision components, precision mechanical parts as well as tools and offers systems and services for the manufacture and joining of textile surfaces. Across the fields of knitting, weaving, felting, tufting, carding or sewing: The portfolio with over 70,000 precision components and industrial machine needles covers the central processes used for the manufacture and joining of textile surfaces. Type of enterprise: Knitting: Application: Limited Commercial Partnership Knitting machine needles, system components and Precision needles and components from Groz-Beckert (in German: KG), family firm cylinders, dials for circular knitting machines give rise to a wide range of applications for different Formation: 1852 Weaving: areas of life. Sectors: Healds, heald frames, warp stop motions, drop wires Textile industry, precision engineering, and machines for weaving preparation Alongside apparel textiles, home and furnishing texti- mechanical engineering Felting: les, technical textiles also play a key role, for instance Production companies: Products for the nonwovens industry, felting and in medical technology, architecture or mobility. Germany, Belgium, Czech Republic, Portugal, structuring needles, jet strips for hydroentanglement USA, India, China, Vietnam Tufting: Sales network: Tufting needles, loopers and tufting knives Worldwide in over 150 countries (individually or as modules), reed finger modules Employees (31.12.2019): Carding: 9,225 Card clothing and accessories for the spinning and Sales (2019): nonwovens industry, mounting service, roller repair, 670 mill. -

The Textile Machinery Collection at the American Textile History Museum a Historic Mechanical Engineering Heritage Collection

THE TEXTILE MACHINERY COLLECTION AT THE AMERICAN TEXTILE HISTORY MUSEUM A HISTORIC MECHANICAL ENGINEERING HERITAGE COLLECTION Textiles are an important part of our everyday lives. They clothe and comfort us, protect our first-responders, Introduction filter the air in our automobiles, and form the core of the fuselage in our newest aircraft. We enjoy their bright colors, wrap up in their warmth, and seldom give a second thought to how they make bicycles stronger and lighter or how they might be used to repair our vital organs. As textiles have changed from the first simple twisted fibers to high-tech smart fabrics, the tools and machinery used to make them have evolved as well. Drop spindles and spinning wheels have given way to long lines of spinning frames. And looms now use puffs of air instead of the human hand to insert the weft thread in a growing length of fabric. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, textile manufacture was the catalyst for the Industrial Revolution in America. It was the leading edge in the transformation from an agricultural to a manufacturing economy and started the move of significant numbers of people from rural areas to urban centers. With industrialization came a change in the way people worked. No longer controlled by natural rhythms, the workday demanded a life governed by the factory bell. On the consumer side, industrialization transformed textiles from one of a person’s most valuable possessions to a product widely available at incredibly low prices. For more than a century, textile mills in Great Britain and the United States dominated textile production and led the industrial revolution in both Europe and North America.