Intelligent Design: a Unique Perspective to the Origins Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Intelligent Design Creationist Movement: Its True Nature and Goals

UNDERSTANDING THE INTELLIGENT DESIGN CREATIONIST MOVEMENT: ITS TRUE NATURE AND GOALS A POSITION PAPER FROM THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY OFFICE OF PUBLIC POLICY AUTHOR: BARBARA FORREST, Ph.D. Reviewing Committee: Paul Kurtz, Ph.D.; Austin Dacey, Ph.D.; Stuart D. Jordan, Ph.D.; Ronald A. Lindsay, J. D., Ph.D.; John Shook, Ph.D.; Toni Van Pelt DATED: MAY 2007 ( AMENDED JULY 2007) Copyright © 2007 Center for Inquiry, Inc. Permission is granted for this material to be shared for noncommercial, educational purposes, provided that this notice appears on the reproduced materials, the full authoritative version is retained, and copies are not altered. To disseminate otherwise or to republish requires written permission from the Center for Inquiry, Inc. Table of Contents Section I. Introduction: What is at stake in the dispute over intelligent design?.................. 1 Section II. What is the intelligent design creationist movement? ........................................ 2 Section III. The historical and legal background of intelligent design creationism ................ 6 Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) ............................................................................ 6 McLean v. Arkansas (1982) .............................................................................. 6 Edwards v. Aguillard (1987) ............................................................................. 7 Section IV. The ID movement’s aims and strategy .............................................................. 9 The “Wedge Strategy” ..................................................................................... -

Intelligent Design, Abiogenesis, and Learning from History: Dennis R

Author Exchange Intelligent Design, Abiogenesis, and Learning from History: Dennis R. Venema A Reply to Meyer Dennis R. Venema Weizsäcker’s book The World View of Physics is still keeping me very busy. It has again brought home to me quite clearly how wrong it is to use God as a stop-gap for the incompleteness of our knowledge. If in fact the frontiers of knowledge are being pushed back (and that is bound to be the case), then God is being pushed back with them, and is therefore continually in retreat. We are to find God in what we know, not in what we don’t know; God wants us to realize his presence, not in unsolved problems but in those that are solved. Dietrich Bonhoeffer1 am thankful for this opportunity to nature, is the result of intelligence. More- reply to Stephen Meyer’s criticisms over, this assertion is proffered as the I 2 of my review of his book Signature logical basis for inferring design for the in the Cell (hereafter Signature). Meyer’s origin of biological information: if infor- critiques of my review fall into two gen- mation only ever arises from intelli- eral categories. First, he claims I mistook gence, then the mere presence of Signature for an argument against bio- information demonstrates design. A few logical evolution, rendering several of examples from Signature make the point my arguments superfluous. Secondly, easily: Meyer asserts that I have failed to refute … historical scientists can show that his thesis by not providing a “causally a presently acting cause must have adequate alternative explanation” for the been present in the past because the origin of life in that the few relevant cri- proposed candidate is the only known tiques I do provide are “deeply flawed.” cause of the effect in question. -

Ono Mato Pee 145

789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 9 789493 148215 789493 9 9 789493 148215 9 148215 789493 148215 789493 9 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 148215 789493 9 789493 148215 9 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 99 789493789493 148215148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 9 789493 148215 145 PEE MATO ONO Graphic Design Systems, and the Systems of Graphic Design Francisco Laranjo Bibliography M.; Drenttel, W. & Heller, S. (2012) Within graphic design, the concept of systems is profoundly Escobar, A. (2018) Designs for Looking Closer 4: Critical Writings rooted in form. When a term such as system is invoked, it is the Pluriverse (New Ecologies for on Graphic Design. Allworth Press, normally related to macro and micro-typography, involving pp. 199–207. the Twenty-First Century). Duke book design and typesetting, but also addressing type design University Press. Manzini, E. (2015) Design, When or parametric typefaces. Branding and signage are two other Jenner, K. (2016) Chill Kendall Jenner Everybody Designs: An Introduction Didn’t Think People Would Care to Design for Social Innovation. domains which nearly claim exclusivity of the use of the That She Deleted Her Instagram. Massachusetts: MIT Press. word ‘systems’ in relation to graphic design. A key example of In: Vogue. Available at: https://www. Meadows, D. (2008) Thinking in this is the influential bookGrid Systems in Graphic Design vogue.com/article/kendall-jenner- Systems. -

The Beginner's Guide to 'Holistic' Wellness

BOOK REVIEWS in the progression of the disease when The Beginner’s Guide to prayer was used” (p. 98). For such a bold statement, the evidence is pretty weak, ‘Holistic’ Wellness however. There are very few studies on DIMITRY ROTSTEIN personal prayer (none are double-blind, of course), and their results are mixed Mayo Clinic Book of Alternative Medicine. By The Mayo even for treating purely psychological Clinic. Time Inc. Home Entertainment Books, New York, symptoms. More disturbing is the fact 2007. ISBN: 1-933405-92-9. 192 pp. Hardcover, $24.95. that the book doesn’t make a distinc- tion between personal and intercessory prayer, even though the latter is known to have no effect according to well-de- he Mayo Clinic Book of mean that perhaps we skeptics have signed studies (including one by the Alterna tive Medicine is the been unfair to “alternative medicine” Mayo Clinic itself). None of these facts most significant publication of and that there is more to it than just T is ever mentioned. In summary, the evi- the Mayo Clinic Complementary and placebo, self-delusion, quackery, or, at dence of the effectiveness of these “ther- Integrative Medicine Program’s team, best, some outdated healing techniques? apies” against any real disease is either which has been studying various forms Perhaps not. dubious or non-existent. Of course, of complementary and alternative medi- True, of the twenty-five CAM ther- controlling such factors as stress and cine (CAM, for short) since 2001. Here apies, fourteen are recommended as depression is important for your health, you will find nothing but reliable and safe and effective for “treating” various but there is no indication that any of the easy-to-understand information from diseases. -

1 Seeing and Believing the Never-Ending Attempt to Reconcile

1 Seeing and Believing The never-ending attempt to reconcile science and religion, and why it is doomed to fail. Jerry A. Coyne, The New Republic Published: Wednesday, February 04, 2009 Saving Darwin: How to be a Christian and Believe in Evolution By Karl W. Giberson (HarperOne, 248 pp., $24.95) Only A Theory: Evolution and the Battle for America's Soul By Kenneth R. Miller (Viking, 244 pp., $25.95) I. Charles Darwin was born on February 12, 1809--the same day as Abraham Lincoln--and published his magnum opus, On the Origin of Species, fifty years later. Every half century, then, a Darwin Year comes around: an occasion to honor his theory of evolution by natural selection, which is surely the most important concept in biology, and perhaps the most revolutionary scientific idea in history. 2009 is such a year, and we biologists are preparing to fan out across the land, giving talks and attending a multitude of DarwinFests. The melancholy part is that we will be speaking more to other scientists than to the American public. For in this country, Darwin is a man of low repute. The ideas that made Darwin's theory so revolutionary are precisely the ones that repel much of religious America, for they imply that, far from having a divinely scripted role in the drama of life, our species is the accidental and contingent result of a purely natural process. And so the culture wars continue between science and religion. On one side we have a scientific establishment and a court system determined to let children learn evolution rather than religious mythology, and on the other side the many Americans who passionately resist those efforts. -

Evolutionary Epistemology in James' Pragmatism J

35 THE ORIGIN OF AN INQUIRY: EVOLUTIONARY EPISTEMOLOGY IN JAMES' PRAGMATISM J. Ellis Perry IV University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth "Much struck." That was Darwin's way of saying that something he observed fascinated him, arrested his attention, surprised or puzzled him. The words "much struck" riddle the pages of bothhis Voyage ofthe Beagle and his The Origin of Species, and their appearance should alert the reader that Darwin was saying something important. Most of the time, the reader caninfer that something Darwin had observed was at variance with what he had expected, and that his fai th in some alleged law or general principle hadbeen shaken, and this happened repeat edly throughout his five year sojourn on the H.M.S. Beagle. The "irritation" of his doubting the theretofore necessary truths of natu ral history was Darwin's stimulus to inquiry, to creative and thor oughly original abductions. "The influence of Darwinupon philosophy resides inhis ha ving conquered the phenomena of life for the principle of transi tion, and thereby freed the new logic for application to mind and morals and life" (Dewey p. 1). While it would be an odd fellow who would disagree with the claim of Dewey and others that the American pragmatist philosophers were to no small extent influenced by the Darwinian corpus,! few have been willing to make the case for Darwin's influence on the pragmatic philosophy of William James. Philip Wiener, in his well known work, reports that Thanks to Professor Perry's remarks in his definitive work on James, "the influence of Darwin was both early and profound, and its effects crop up in unex pected quarters." Perry is a senior at the University of Massachusetts at Dartmoltth. -

Arguments from Design

Arguments from Design: A Self-defeating Strategy? Victoria S. Harrison University of Glasgow This is an archived version of ‘Arguments form Design: A Self-defeating Strategy?’, published in Philosophia 33 (2005): 297–317. Dr V. Harrison Department of Philosophy 69 Oakfield Avenue University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8LT Scotland UK E-mail: [email protected] Arguments from Design: A Self-defeating Strategy? Abstract: In this article, after reviewing traditional arguments from design, I consider some more recent versions: the so-called ‘new design arguments’ for the existence of God. These arguments enjoy an apparent advantage over the traditional arguments from design by avoiding some of Hume’s famous criticisms. However, in seeking to render religion and science compatible, it seems that they require a modification not only of our scientific understanding but also of the traditional conception of God. Moreover, there is a key problem with arguments from design that Mill raised to which the new arguments seem no less vulnerable than the older versions. The view that science and religion are complementary has at least one significant advantage over other positions, such as the view that they are in an antagonistic relationship or the view that they are so incommensurable that they are neither complementary nor antagonistic. The advantage is that it aspires to provide a unified worldview that is sensitive to the claims of both science and religion. And surely, such a worldview, if available, would seem to be superior to one in which, say, scientific and religious claims were held despite their obvious contradictions. -

The Demarcation Problem

Part I The Demarcation Problem 25 Chapter 1 Popper’s Falsifiability Criterion 1.1 Popper’s Falsifiability Popper’s Problem : To distinguish between science and pseudo-science (astronomy vs astrology) - Important distinction: truth is not the issue – some theories are sci- entific and false, and some may be unscientific but true. - Traditional but unsatisfactory answers: empirical method - Popper’s targets: Marx, Freud, Adler Popper’s thesis : Falsifiability – the theory contains claims which could be proved to be false. Characteristics of Pseudo-Science : unfalsifiable - Any phenomenon can be interpreted in terms of the pseudo-scientific theory “Whatever happened always confirmed it” (5) - Example: man drowning vs saving a child Characteristics of Science : falsifiability - A scientific theory is always takes risks concerning the empirical ob- servations. It contains the possibility of being falsified. There is con- firmation only when there is failure to refute. 27 28 CHAPTER 1. POPPER’S FALSIFIABILITY CRITERION “The theory is incompatible with certain possible results of observation” (6) - Example: Einstein 1919 1.2 Kuhn’s criticism of Popper Kuhn’s Criticism of Popper : Popper’s falsifiability criterion fails to char- acterize science as it is actually practiced. His criticism at best applies to revolutionary periods of the history of science. Another criterion must be given for normal science. Kuhn’s argument : - Kuhn’s distinction between normal science and revolutionary science - A lesson from the history of science: most science is normal science. Accordingly, philosophy of science should focus on normal science. And any satisfactory demarcation criterion must apply to normal science. - Popper’s falsifiability criterion at best only applies to revolutionary science, not to normal science. -

Mike Kelley's Studio

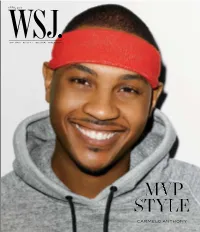

No PMS Flood Varnish Spine: 3/16” (.1875”) 0413_WSJ_Cover_02.indd 1 2/4/13 1:31 PM Reine de Naples Collection in every woman is a queen BREGUET BOUTIQUES – NEW YORK FIFTH AVENUE 646 692-6469 – NEW YORK MADISON AVENUE 212 288-4014 BEVERLY HILLS 310 860-9911 – BAL HARBOUR 305 866-1061 – LAS VEGAS 702 733-7435 – TOLL FREE 877-891-1272 – WWW.BREGUET.COM QUEEN1-WSJ_501x292.indd 1-2 01.02.13 16:56 BREGUET_205640303.indd 2 2/1/13 1:05 PM BREGUET_205640303.indd 3 2/1/13 1:06 PM a sporting life! 1-800-441-4488 Hermes.com 03_501,6x292,1_WSJMag_Avril_US.indd 1 04/02/13 16:00 FOR PRIVATE APPOINTMENTS AND MADE TO MEASURE INQUIRIES: 888.475.7674 R ALPHLAUREN.COM NEW YORK BEVERLY HILLS DALLAS CHICAGO PALM BEACH BAL HARBOUR WASHINGTON, DC BOSTON 1.855.44.ZEGNA | Shop at zegna.com Passion for Details Available at Macy’s and macys.com the new intense fragrance visit Armanibeauty.com SHIONS INC. Phone +1 212 940 0600 FA BOSS 0510/S HUGO BOSS shop online hugoboss.com www.omegawatches.com We imagined an 18K red gold diving scale so perfectly bonded with a ceramic watch bezel that it would be absolutely smooth to the touch. And then we created it. The result is as aesthetically pleasing as it is innovative. You would expect nothing less from OMEGA. Discover more about Ceragold technology on www.omegawatches.com/ceragold New York · London · Paris · Zurich · Geneva · Munich · Rome · Moscow · Beijing · Shanghai · Hong Kong · Tokyo · Singapore 26 Editor’s LEttEr 28 MasthEad 30 Contributors 32 on thE CovEr slam dunk Fashion is another way Carmelo Anthony is scoring this season. -

Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It?

Leaven Volume 17 Issue 2 Theology and Science Article 6 1-1-2009 Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? Chris Doran [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Doran, Chris (2009) "Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It?," Leaven: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/leaven/vol17/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Leaven by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Doran: Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? Intelligent Design: Is It Really Worth It? CHRIS DORAN imaginethatwe have all had occasion to look up into the sky on a clear night, gaze at the countless stars, and think about how small we are in comparison to the enormity of the universe. For everyone except Ithe most strident atheist (although I suspect that even s/he has at one point considered the same feeling), staring into space can be a stark reminder that the universe is much grander than we could ever imagine, which may cause us to contemplate who or what might have put this universe together. For believers, looking up at tJotestars often puts us into the same spirit of worship that must have filled the psalmist when he wrote, "The heavens declare the glory of God; the skies proclaim the work of his hands" (Psalms 19.1). -

Intelligent Design Is Not Science” Given by John G

An Outline of a lecture entitled, “Intelligent Design is not Science” given by John G. Wise in the Spring Semester of 2007: Slide 1 Why… … do humans have so much trouble with wisdom teeth? … is childbirth so dangerous and painful? Because a big, thinking brain is an advantage, and evolution is imperfect. Slide 2 Charles Darwin’s Revolutionary Idea His book changed the world. All life forms on this planet are related to each other through “Descent with modification over generations from a common ancestor”. Natural processes fully explain the biological connections between all life on the planet. Slide 3 Darwin’s Idea is Dangerous (from the book of the same title by Daniel Dennett) If we have evolution, we no longer need a Creator to create each and every species. Darwinism is dangerous because it infers that God did not directly and purposefully create us. It simply states that we evolved. Slide 4 Intelligent Design Attempts to Counter Darwin “Intelligent Design” has been proposed as way out of this dilemma. – Phillip Johnson, William Dembski, and Michael Behe (to name a few). They attempt to redefine science to encompass the supernatural as well as the natural world. They accept Darwin’s evolution, if an Intelligent Designer is (sometimes) substituted for natural selection. Design arguments are not new: − 1250 - St. Thomas Aquinas - first design argument − 1802 - Natural Theology - William Paley – perhaps the best(?) design argument Slide 5 What is Science? A specific way of understanding the natural world. Based on the idea that our senses give us accurate information about the Universe. -

Searching for Security in the Mystical the Function of Paranormal Beliefs

Searching for Security in the Mystical The Function of Paranormal Beliefs MARTIN R. GRIMMER ver the past two decades, the paranor- mal has enjoyed something of a revival Owithin popular culture. There have been countless books, magazine and newspaper articles, movies, and television programs devoted to topics ranging from UFOs, the Bermuda Triangle, lost continents, Yetis, and Belief in the the Loch Ness monster, to pyramid power, astrology, levitation, telepathy, precognition, paranormal and poltergeists. Sociologist Marcello Truzzi appears to satisfy (1972) suggested that this boom in paranormal interest began around the late sixties, noting some very basic, if that Ouija boards outsold such popular board inconsistent games as Monopoly. human needs. It Lately, the paranormal seems to have mani- fested in the form of the New Age movement— will probably a loose combination of ideas encompassing spir- remain with us itualism, mysticism, alternative healing, and a healthy dose of commercialism. Some may think forever. this is mainly an American phenomenon, but it is estimated that Australians alone now spend $100 million a year on personal-transformation courses that delve deeply into such fringe areas as rebirthing, shamanism, channeling, and crystal healing. To some observers, the New Age movement is seen as a sort of quasi-religious justification for "yuppiedom"—how to make money and feel "really great" about it at the same time. Winter 1992 Research studies worldwide have written on this topic, several themes revealed an extensive belief in and in the human motive to believe can acceptance of the paranormal. In a be identified. survey of the readers of Britain's New First, paranormal beliefs may oper- Scientist magazine, a high proportion ate to reassure the believer that there of whom are reported to hold post- is order and control in what may graduate degrees, Evans (1973) found otherwise appear to be a chaotic that 67 percent believed that ESP was universe (Frank 1977).