Searching for Security in the Mystical the Function of Paranormal Beliefs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grade 6 Reading Student At–Home Activity Packet

Printer Warning: This packet is lengthy. Determine whether you want to print both sections, or only print Section 1 or 2. Grade 6 Reading Student At–Home Activity Packet This At–Home Activity packet includes two parts, Section 1 and Section 2, each with approximately 10 lessons in it. We recommend that your student complete one lesson each day. Most lessons can be completed independently. However, there are some lessons that would benefit from the support of an adult. If there is not an adult available to help, don’t worry! Just skip those lessons. Encourage your student to just do the best they can with this content—the most important thing is that they continue to work on their reading! Flip to see the Grade 6 Reading activities included in this packet! © 2020 Curriculum Associates, LLC. All rights reserved. Section 1 Table of Contents Grade 6 Reading Activities in Section 1 Lesson Resource Instructions Answer Key Page 1 Grade 6 Ready • Read the Guided Practice: Answers will vary. 10–11 Language Handbook, Introduction. Sample answers: Lesson 9 • Complete the 1. Wouldn’t it be fun to learn about Varying Sentence Guided Practice. insect colonies? Patterns • Complete the 2. When I looked at the museum map, Independent I noticed a new insect exhibit. Lesson 9 Varying Sentence Patterns Introduction Good writers use a variety of sentence types. They mix short and long sentences, and they find different ways to start sentences. Here are ways to improve your writing: Practice. Use different sentence types: statements, questions, imperatives, and exclamations. Use different sentence structures: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. -

Rebirthing: the Transformation of Personhood Through Embodiment and Emotion

Rebirthing: the transformation of personhood through embodiment and emotion Elise Carr The University of Adelaide School of Social Sciences Discipline of Anthropology and Development Studies July 2014 Thesis Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution in my name and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University‘s digital research repository, the Library catalogue and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. Elise Carr TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. VI ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................... -

The Beginner's Guide to 'Holistic' Wellness

BOOK REVIEWS in the progression of the disease when The Beginner’s Guide to prayer was used” (p. 98). For such a bold statement, the evidence is pretty weak, ‘Holistic’ Wellness however. There are very few studies on DIMITRY ROTSTEIN personal prayer (none are double-blind, of course), and their results are mixed Mayo Clinic Book of Alternative Medicine. By The Mayo even for treating purely psychological Clinic. Time Inc. Home Entertainment Books, New York, symptoms. More disturbing is the fact 2007. ISBN: 1-933405-92-9. 192 pp. Hardcover, $24.95. that the book doesn’t make a distinc- tion between personal and intercessory prayer, even though the latter is known to have no effect according to well-de- he Mayo Clinic Book of mean that perhaps we skeptics have signed studies (including one by the Alterna tive Medicine is the been unfair to “alternative medicine” Mayo Clinic itself). None of these facts most significant publication of and that there is more to it than just T is ever mentioned. In summary, the evi- the Mayo Clinic Complementary and placebo, self-delusion, quackery, or, at dence of the effectiveness of these “ther- Integrative Medicine Program’s team, best, some outdated healing techniques? apies” against any real disease is either which has been studying various forms Perhaps not. dubious or non-existent. Of course, of complementary and alternative medi- True, of the twenty-five CAM ther- controlling such factors as stress and cine (CAM, for short) since 2001. Here apies, fourteen are recommended as depression is important for your health, you will find nothing but reliable and safe and effective for “treating” various but there is no indication that any of the easy-to-understand information from diseases. -

Urban Myths Mythical Cryptids

Ziptales Advanced Library Worksheet 2 Urban Myths Mythical Cryptids ‘What is a myth? It is a story that pretends to be real, but is in fact unbelievable. Like many urban myths it has been passed around (usually by word of mouth), acquiring variations and embellishments as it goes. It is a close cousin of the tall tale. There are mythical stories about almost any aspect of life’. What do we get when urban myths meet the animal kingdom? We find a branch of pseudoscience called cryptozoology. Cryptozoology refers to the study of and search for creatures whose existence has not been proven. These creatures (or crytpids as they are known) appear in myths and legends or alleged sightings. Some examples include: sea serpents, phantom cats, unicorns, bunyips, giant anacondas, yowies and thunderbirds. Some have even been given actual names you may have heard of – do Yeti, Owlman, Mothman, Cyclops, Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster sound familiar? Task 1: Choose one of the cryptids from the list above (or perhaps one that you may already know of) and write an informative text identifying the following aspects of this mythical creature: ◊ Description ◊ Features ◊ Location ◊ First Sighting ◊ Subsequent Sightings ◊ Interesting Facts (e.g. how is it used in popular culture? Has it been featured in written or visual texts?) Task 2: Cryptozoologists claim there have been cases where species now accepted by the scientific community were initially considered urban myths. Can you locate any examples of creatures whose existence has now been proven but formerly thought to be cryptids? Extension Activities: • Cryptozoology is called a ‘pseudoscience’ because it relies solely on anecdotes and reported sightings rather than actual evidence. -

Organising an EDE - Available to Certified Host Sites

Fall 08 Ecovillage Design Education A four-week comprehensive course in the fundamentals of Sustainability Design Curriculum conceived and designed by the GEESE—Global Ecovillage Educators for a Sustainable Earth Version 5 © Gaia Education, 2012 www.gaiaeducation.net 1 Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................... 2 The Sustainability Wheel .................................................................................... 5 Why is Gaia Education necessary? .................................................................. 7 Worldview Overview .................................................................................................................................................... 11 Module 1: Holistic Worldview .......................................................................................................... 13 Module 2: Reconnecting with Nature .......................................................................................... 16 Module 3: Transformation of Consciousness ............................................................................ 19 Module 4: Personal Health and Planetary Health ................................................................... 21 Module 5: Socially Engaged Spirituality .................................................................................... 24 Social Overview ................................................................................................................................................... -

The Pseudoscience of Anti-Anti-Ufology

SI Sept/Oct 2009 pgs 7/29/09 11:24 AM Page 28 PSYCHIC VIBRATIONS ROBERT SHEAFFER The Pseudoscience of Anti-Anti-UFOlogy Many readers are surely familiar with is more their style. Deception is the practiced prestidigitation can never be author and pro-UFO lecturer Stanton T. name of the game.” trusted in anything. He criticizes Friedman, who calls himself the “Flying Friedman goes on to name names: Nickell for raising “the baseless Project Saucer physicist” because he actually did He critiques Joe Nickell’s article “Return Mogul explanation” for Roswell, which work in physics about fifty years ago (al- cannot be correct, says Friedman, though not since). Well, Stanton is upset because it does not match the claims by the skeptical writings contained in made in later years by alleged Roswell SI’s special issue on UFOs (January- witnesses (although it does match quite /February 2009) and elsewhere. He has well the account of Mac Brazel, the orig- written two papers thus far denouncing inal witness, given in 1947). us, and it is the subject of his Keynote He moves on to my critique of the Address at the MUFON Conference in Betty and Barney Hill case, where I note August. the resemblance of their “hypnosis UFO In February, Friedman wrote an arti- testimony” to Betty Hill’s post-incident cle, “Debunkers at it Again,” reviewing dreams. I wrote, “Barney had heard her our UFO special issue (www.theufo repeat [them] many times,” which he chronicles.com/2009/02/debunkers-at- claims is “nonsense.” According to it-again.html). -

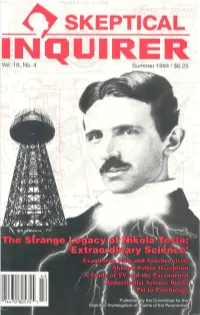

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

Carnot Travelogue - Scotland 2015

Avant-propos Au pays des Lochs et des légendes Ce voyage s'est déroulé du 7 au 14 mai 2015. Nous avons passé une semaine délicieuse en compagnie des élèves de la classe de 1S1 euro SVT, 3 élèves de 2nde 8 euro SVT et 1 élève de 1E1. Des Lowlands aux Highlands, d'Édimbourg à Stirling, Saint Andrews, Inverness... Châteaux et Cathédrales, héros et légendes, paysages spectaculaires entre lochs et collines... sans oublier la rencontre avec Nessie, monstre sympathique du Loch Ness... Chaque élève a rédigé un carnet de voyage (Travelogue) de plus d'une dizaine de pages (one page a day. Or more!) émaillé d'anecdotes, de photos et d'émotions... Nous espérons que nos élèves garderont ces images en mémoire, tout comme nous... Voici ci-après un compte-rendu de chaque jour de la semaine, extraits de plusieurs « travelogues ». Enjoy ! Nous tenons à remercier tous les élèves pour leur investissement, leur fraîcheur, leur sens de l'humour, leur enthousiasme, leurs sourires, et surtout... leur ponctualité tout au long de la semaine. Merci aussi à leurs parents pour avoir rendu possible leur découverte de ce pays « de Lochs et de légendes ». Et un grand merci aussi à José Torrecilla pour sa précieuse collaboration pendant ces huit jours... ! My heart's in the Highlands. The birth-place of Valour, the country of Worth; Wherever I wander, wherever I rove, The hills of the Highlands for ever I love. ROBERT BURNS 1759-1796 Muriel Garnier et Valérie Rapin Professeurs d’anglais au Lycée Carnot Travel through Scotland 3 Day 1 Departure Thursday May 7th 2015 was such a great day… We began our trip to Scotland early in the morning, at 3:50 AM. -

The Case of Astrology –

The relation between paranormal beliefs and psychological traits: The case of Astrology – Brief report Antonis Koutsoumpis Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Author Note Antonis Koutsoumpis ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9242-4959 OSF data: https://osf.io/62yfj/?view_only=c6bf948a5f3e4f5a89ab9bdd8976a1e2 I have no conflicts of interest to disclose Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: De Boelelaan 1105, 1081HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Email: [email protected] The present manuscript briefly reports and makes public data collected in the spring of 2016 as part of my b-thesis at the University of Crete, Greece. The raw data, syntax, and the Greek translation of scales and tasks are publicly available at the OSF page of the project. An extended version of the manuscript (in Greek), is available upon request. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first public dataset on the astrological and paranormal beliefs in Greek population. Introduction The main goal of this work was to test the relation between Astrological Belief (AB) to a plethora of psychological constructs. To avoid a very long task, the study was divided into three separate studies independently (but simultaneously) released. Study 1 explored the relation between AB, Locus of Control, Optimism, and Openness to Experience. Study 2 tested two astrological hypotheses (the sun-sign and water-sign effects), and explored the relation between personality, AB, and zodiac signs. Study 3 explored the relation between AB and paranormal beliefs. Recruitment followed both a snowball procedure and it was also posted in social media groups of various Greek university departments. -

Naming the Loch Ness Monster

Nature Vol. 258 December 11 1975 Naming the Loch Ness monster Recent publicity concerning new claims for the existence of the Loch Ness monster has focused on the evidence offered by Sir Peter Scott and Robert Rines. Here, in an article planned to coincide with the now-cancelled symposium in Edinburgh at which the whole issue was due to be discussed, they point out that recent British legislation makes provision for protection to be given to endangered species; to he granted protection, however, an animal should first be given a proper scientific name. Better, they argue, to be safe than sorry; a name for a species whose existence is still a matter of controversy among many scientists is preferable to none if its protection is to be assured. The name suggested is Nessiteras rhombopteryx. CHEDULE 1 of the Conservation light illuminates an area of the animal's S of Wild Creatures and Wild Plants back and belly with a rough skin Act, 1975, passed recently by the UK texture. In the upper photograph Parliament, provides the best way of there is what may be some suggestion giving full protection to any animal of ribs. whose survival is threatened. To be Although these two photographs Fig. 1 Photographs taken by strobe flash at included, an animal should be given a of the hind flipper are the main basis of a depth of 45 feet in Loch Ness at 0150 h on common name and a scientific name. the description, and the flipper-length August 8, 1972, showing the right hind flipper, calculated as about 2 m long, of For the Nessie or Loch Ness monster, is thought to be some 2 m, it is possible, Nessiteras rhombopteryx. -

Violent Video Games: Dogma, Fear, and Pseudoscience

SI Sept/Oct 2009 pgs 7/22/09 2:33 PM Page 38 Violent Video Games: Dogma, Fear, and Pseudoscience Video games are at the center of a modern media-based moral panic. Too often, social scientists have fueled the flames and eschewed good scientific practices. CHRISTOPHER J. FERGUSON chool shootings at high schools and universities are rare but shocking events. Across the last decade or so Swe have come to understand a little about the psychol- ogy of the young men who carry out such horrific crimes. Most typically they are emotionally disturbed, often de- pressed, feel socially isolated and alienated from society, and are filled with rage and hatred. It is natural for society to want easy answers about how such a phenomenon can be controlled. Social scientists want to give those answers. Unfortunately, the human inclination to believe we can pre- dict the unpredictable and control the uncontrollable often leads us to mask the language of fear and irrationality in the language of science. 38 Volume 33, Issue 5 SKEPTICAL INQUIRER SI Sept/Oct 2009 pgs 7/22/09 2:33 PM Page 39 In the case of school shootings and youth violence in gen- son and David Grossman might be forgiven for inflaming fears eral, some scientists have answered the public demand for a with exaggerated claims. Grossman, for instance, has promul- culprit. The alleged corrupting influence of violent video gated the false notion that the military uses video games to games has been identified by some as one root cause. Ignoring desensitize soldiers to killing (they do use simulators for visual the youth-violence data, ignoring inconsistent data from mul- scanning and reaction time and vehicle training, but they seem tiple studies, even ignoring contradictory data from their own more effective in reducing accidental shootings than anything studies, some social scientists have presented the research on else). -

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 1818,, No . 2No. 2 ^^ Winter 1994 Winter / 1994/$6.2$6.255 Paul Kurtz William Grey THE NEW THE PROBLEM SKEPTICISM OF 'PSI' Cancer Scares i*5"***-"" —-^ 44 "74 47CT8 3575" 5 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Computer Assistant Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Asst. Managing Editor Cynthia Matheis. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). Cartoonist Rob Pudim. The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, "author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ.