Dietary Contribution of Wild Edible Plants to Women's Diets in the Buffer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE and PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS of Ipomoea Aquatica Forssk

UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE AND PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. WITH ITS ANTIOXIDANT AND α-GLUCOSIDASE INHIBITORY ACTIVITIES USING NMR-BASED METABOLOMICS UMAR LAWAL FSTM 2016 4 CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE AND PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. WITH ITS ANTIOXIDANT AND α-GLUCOSIDASE INHIBITORY ACTIVITIES USING NMR-BASED METABOLOMICS UPM By UMAR LAWAL COPYRIGHT Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy © March 2016 All material contained within the thesis, including without limitation text, logos, icons, photographs and all other artwork, is copyright material of Universiti Putra Malaysia unless otherwise stated. Use may be made of any material contained within the thesis for non-commercial purposes from the copyright holder. Commercial use of material may only be made with the express, prior, written permission of Universiti Putra Malaysia. Copyright © Universiti Putra Malaysia. UPM COPYRIGHT © DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents and family UPM COPYRIGHT © Abstract of thesis presented to the Senate of Universiti Putra Malaysia in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy CORRELATION BETWEEN METABOLITE PROFILE AND PHYTOCHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. WITH ITS ANTIOXIDANT AND α-GLUCOSIDASE INHIBITORY ACTIVITIES USING NMR-BASED METABOLOMICS By UMAR LAWAL March 2016 UPM Chairman : Associate Professor Faridah Abas, PhD Faculty : Food Science and Technology Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. (morning glory) is a green leafy vegetable that is rich in minerals, proteins, vitamins, amino acids and secondary metabolites. The aims of the study were to discriminate Ipomoea extracts by 1H NMR spectroscopy in combination with chemometrics method and to determine their antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. -

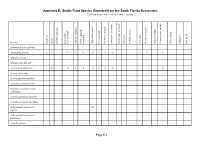

MSRP Appendix E

Appendix E. Exotic Plant Species Reported from the South Florida Ecosystem. Community types are indicated where known Species High Pine Scrub Scrubby high pine Beach dune/ Coastal strand Maritime hammock Mesic temperate hammock Tropical hardwood Pine rocklands Scrubby flatwoods Mesic pine flatwoods Hydric pine flatwoods Dry prairie Cutthroat grass Wet prairie Freshwater marsh Seepage swamp Flowing water swamp Pond swamp Mangrove Salt marsh Abelmoschus esculentus Abrus precatorius X X X X X X X X X X X X Abutilon hirtum Abutilon theophrasti Acacia auriculiformis X X X X X X X X X Acacia retinoides Acacia sphaerocephala Acalypha alopecuroidea Acalypha amentacea ssp. wilkesiana Acanthospermum australe Acanthospermum hispidum Achyranthes aspera var. X aspera Achyranthes aspera var. pubescens Acmella pilosa Page E-1 Species High Pine Scrub Scrubby high pine Beach dune/ Coastal strand Maritime hammock Mesic temperate hammock Tropical hardwood Pine rocklands Scrubby flatwoods Mesic pine flatwoods Hydric pine flatwoods Dry prairie Cutthroat grass Wet prairie Freshwater marsh Seepage swamp Flowing water swamp Pond swamp Mangrove Salt marsh Acrocomia aculeata X Adenanthera pavonina X X Adiantum anceps X Adiantum caudatum Adiantum trapeziforme X Agave americana Agave angustifolia cv. X marginata Agave desmettiana Agave sisalana X X X X X X Agdestis clematidea X Ageratum conyzoides Ageratum houstonianum Aglaonema commutatum var. maculatum Ailanthus altissima Albizia julibrissin Albizia lebbeck X X X X X X X Albizia lebbeckoides Albizia procera Page -

Appendix 9.2 Plant Species Recorded Within the Assessment Area

Appendix 9.2: Plant Species Recorded within the Assessment Area Agricultural Area Storm Water Fishponds Mudflat / Native/ Developed Distribution in Protection Village / Drain / Natural Modified and Coastal Scientific Name Growth Form Exotic to Area / Plantation Grassland Shrubland Woodland Marsh Mangrove Hong Kong (1) Status Orchard Recreational Watercourse Watercourse Mitigation Water Hong Kong Wasteland Dry Wet Pond Ponds Body Abrus precatorius climber: vine native common - + subshrubby Abutilon indicum native restricted - ++ herb Acacia auriculiformis tree exotic - - ++++ +++ + ++++ ++ +++ Acacia confusa tree exotic - - ++++ + +++ ++ ++ ++++ ++ ++++ Acanthus ilicifolius shrub native common - + ++++ Acronychia pedunculata tree native very common - ++ Adenosma glutinosum herb native very common - + + Adiantum capillus-veneris herb native common - + ++ ++ Adiantum flabellulatum herb native very common - + +++ +++ shrub or small Aegiceras corniculatum native common - +++ tree Aeschynomene indica shrubby herb native very common - + Ageratum conyzoides herb exotic common - ++ ++ ++ ++ ++ + Ageratum houstonianum herb exotic common - ++ + Aglaia odorata shrub exotic common - +++ + +++ + Aglaonema spp. herb - - - + + rare (listed under Forests and Ailanthus fordii (3) small tree native + Countryside Ordinance Cap. 96) Alangium chinense tree or shrub native common - ++ + ++ + +++ + Albizia lebbeck tree exotic - - +++ Alchornea trewioides shrub native common - + Aleurites moluccana tree exotic common - +++ ++ ++ ++ Allamanda cathartica climbing -

Effects of Water Spinach Ipomoea Aquatica Cultivation on Water Quality and Performance of Chinese Soft-Shelled Turtle Pelodiscus Sinensis Pond Culture

Vol. 8: 567–574, 2016 AQUACULTURE ENVIRONMENT INTERACTIONS Published September 30 doi: 10.3354/aei00198 Aquacult Environ Interact OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Effects of water spinach Ipomoea aquatica cultivation on water quality and performance of Chinese soft-shelled turtle Pelodiscus sinensis pond culture Wei Li1,2, Huaiyu Ding3, Fengyin Zhang4, Tanglin Zhang1, Jiashou Liu1, Zhongjie Li1,* 1State Key Laboratory of Freshwater Ecology and Biotechnology, Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430072, China 2School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington, Box 355020, Seattle, Washington 98195-5020, USA 3Jiangsu Engineering Laboratory for Breeding of Special Aquatic Organisms, Huaiyin Normal University, Huaian 223300, China 4College of Life Sciences, Jianghan University, Wuhan 430056, China ABSTRACT: The Chinese soft-shelled turtle Pelodiscus sinensis is a highly valued freshwater spe- cies cultured in China. A 122 d experiment was conducted to assess the effects of water spinach Ipomoea aquatica cultivation in floating beds on water quality, and growth performance and eco- nomic return of P. sinensis cultured in ponds. Two treatments, each in triplicate, with and without I. aquatica cultivation were designed. Results showed that the levels of total ammonia nitrogen (TAN), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), chlorophyll a (chl a) and turbidity in treatments with I. aquatica cultivation (IAC) were significantly (p < 0.05) lower than those in treatments with- out I. aquatica (control). Mean TN and TP concentrations in the IAC treatment were 27.9 and 42.5%, respectively, lower than in the control treatment at the end of the experiment. The pres- ence of I. aquatica also has a positive effect on the performance of P. -

Technical Working Party for Vegetables Fifty-Third Session Seoul, Republic of Korea, May 20 to 24, 2019 REVISED REPORT Adopted B

E International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants Technical Working Party for Vegetables TWV/53/14 Rev. Fifty-Third Session Original: English Seoul, Republic of Korea, May 20 to 24, 2019 Date: August 30, 2019 REVISED REPORT Adopted by the Technical Working Party for Vegetables (TWV) Disclaimer: this document does not represent UPOV policies or guidance Opening of the session 1. The Technical Working Party for Vegetables (TWV) held its fifty-third session in Seoul, Republic of Korea, from May 20 to 24, 2019. The list of participants is reproduced in Annex I to this report. 2. The session was opened by Ms. Romana Bravi (Italy), Chairperson of the TWV, who welcomed the participants and thanked the Republic of Korea for hosting the TWV session. 3. The TWV was welcomed by Mr. Choi Byungkook, General Director, International Development and Cooperation Division, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MAFRA). 4. The TWV received a presentation on plant variety protection in the Republic of Korea by Mr. Pang Munjin, Director, Plant Variety Protection Division, Korea Seed and Variety Service (KSVS). A copy of the presentation is provided in Annex II to this report. Adoption of the agenda 5. The TWV adopted the agenda as presented in document TWV/53/1 Rev. Short Reports on Developments in Plant Variety Protection (a) Reports on developments in plant variety protection from members and observers 6. The TWV noted the information on developments in plant variety protection from members and observers, provided in document TWV/53/3 Prov. The TWV noted that reports submitted to the Office of the Union after May 14, 2019, would be included in the final version of document TWV/53/3. -

Nutritional Value of Cambodian Crops

Nutritional Value of Common Fruits & Vegetables Grown in Cambodia Note: Recent research in Cambodia and other developing countries shows that the most common micro-nutrient deficiencies (especially among women and children) are: anemia (lack of iron), night blindness (lack of enough Vitamin A), and goiter/iodine deficiency (although in Cambodia they are promoting iodized salt, and a lot of people now use it). Additionally, protein deficiency is always a leading factor in severe malnutrition. See page 8 for recommended daily intakes. Nutritional value of foods is based on the USDA database. Note that this is the value per 100 grams of raw, uncooked foods (unless otherwise noted); keep in mind that most vegetables lose nutrients the longer you cook them. English Khmer Common Scientific Name Nutritional value per 100 grams (raw/uncooked) Image Common Name Name Energy Protein Vit. A Vit. C Iron Other significant (kcal) (g) (IU) (mg) (mg) nutrients Allium cepa bulb onion ខ្ឹមបរំង 38 1.2 0 11 .8 k'teum barang 215mg Calcium Amaranthus tricolor leafy amaranth ផ្ី 23 46 2,917 43.3 2.32 p'tee 611 mg Potassium peanut Arachis សែណ្កដី 570 25 3 1 3.8 groundnut son-dyk die Page 1 Scientific Name English Khmer Energy Protein Vit. A Vit. C Iron Other nutrients Artocarpus jackfruit ខ្ុរ 95 1.72 110 13.7 .23 heterophyllus k'no wax gourd Benincasa hispida wintermelon ្តឡច 13 .4 10 13 .4 traa-lak fuzzy bourd Brassica juncea mustard greens ៃស្ៅខ្ 22 2.2 9,900 130 spy k'mao 135 mg Calcium Brassica oleracea, var. -

Convolvulaceae) in Southern Nigeria

Annals of West University of Timişoara, ser. Biology, 2018, vol. 21 (1), pp.29-46 COMPARATIVE MORPHOLOGY OF LEAF EPIDERMIS IN THE GENUS IPOMOEA (CONVOLVULACEAE) IN SOUTHERN NIGERIA Kehinde Abiola BOLARINWA 1, Oyetola Olusegut OYEBANJI 2, James Dele OLOWOKUDEJO 2 1Biology Unit, Distance Learning Institute, University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos, Nigeria 2Department of Botany, University of Lagos, Nigeria *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] Received 15 March 2018; accepted 8 May 2018 ABSTRACT Leaf epidermal morphology of eight species of Ipomoea found in Southern Nigeria has been studied using light microscope. Epidermal characters such as stomata type, epidermal cell type, anticlinal wall patterns, trichomes, presence of glands, stomata number and size, epidermal cell number and size, cell wall thickness, gland number and gland length vary within and amongst the species. The cells of adaxial and abaxial epidermises are polygonal or irregular with straight, sinuous or curved anticlinal wall pattern. Stomata are present on both adaxial and abaxial surfaces. Stomata complex is paracytic except in I. asarifolia and I. purpurea where its staurocytic; stomata index is higher on the abaxial side while trichome is absent on the abaxial surface of I. cairica and I. purpurea, likewise on the adaxial surface of I. involucrata. Glands are observed in all the species. Interspecific variation was further revealed in the quantitative micromorphology characters of Ipomoea species studied which was statistically supported at p<0.001 significance level. The taxonomic significance of these features in identification and elucidation of species affinity is discussed. KEY WORDS: Ipomoea, epidermal cell, stomata type, taxonomy, quantitative and qualitative characters. -

Dicots & Gymnosperms

Institute For Regional Conservation Dicots & Gymnosperms Institute For Regional Conservation Scientific Name Common Name Origin State Stat. IRC Stat. Wund.Stat. DICOTS Abelmoschus esculentus Okra Abrus precatorius Rosary-pea Abutilon hirtum Indian mallow HZ' Abutilon perm Ile c"-L ./ at) Indian mallow R3 Abutilon theophrast Velvet leaf Acacia auriculiformis Earleaf acacia E Acacia choriophylla R1 Acacia farnesiana Sweet acacia Acacia macracantha R1 Acacia pinetorum Pineland acacia R3 Acacia retinoides Acacia simplicifolia Acacia sphaerocephala Acacia tortuosa RX Acalypha alopecuroidea Acalypha amentacea ssp. wilkesiana Acalypha chamaedrifolia • Three-seeded mercury R4 Acalypha graciliens R1 Acalypha hispida Acalypha ostryifolia R3 itS10* Acanthocereus tetragon Barbwire cactus R3 Acanthospermum hispidum C Acer rubrum Southern red maple R4 Achyranthes aspera var. aspera Common Devil's-horsewhip Achyranthes aspera var. pubescens Hairy Devil's-horsewhip Acmella oppositifolia var. repens R3 Acmella pilosa Adenanthera pavonina Sandalwood Aeschynomene americana Aeschynomene indica Aeschynomene pratensis Sensitive joint-vetch R1 Aeschynomene viscidula R2 Agalinis fasciculata R3 Agalinis filifolia R2 Agalinis linifolia R2 Agalinis maritima R3 Agalinis obtusifolia R2 Agdestis clematidea Ageratina jucunda R3 Ageratum conyzoides Ageratum houstonianum Ageratum Morale Keys ageratum R2 Ailanthus altissima Tree-of-heaven Albizia julibrissin Albizia lebbeck Woman's tongue Albizia lebbeckoides Albizia procera Alectryon coriaceus Smooth rambutton Aleurites -

Ipomoea Aquatica Forsskal Convolvulaceae/Morning-Glory Family

Ipomoea aquatica Forsskal Convolvulaceae/Morning-Glory Family Common Names: Water-spinach, Chinese water-spinach or morning-glory, water bindweed Synonymy: Ipomoea repens Roth, I. reptans Poiret, Convolvulus repens Vahl Origin: Central to south China Botanical Description: Herbaceous trailing vine with milky sap. Stems hollow, to 3 m (9 ft) long or more, rooting at nodes, floating in aquatic situations. Leaves alternate, simple, with glabrous petioles 3-14 cm (1-6 in) long; leaf blades generally arrowhead shaped but variable, glabrous or rarely pilose, to 17 cm (7 in) long, with tips pointed; blades held above water when stems floating. Flowers showy, funnelform like morning- glory blooms, solitary or in few-flowered clusters at leaf axils; petals white or pink-lilac. Fruit an oval or spherical capsule, woody at maturity, about 1 cm (1/2 in) wide, holding 1-4 grayish seeds, these often short-hairy. NOTE: Two basic forms (with many cultivars of each) recognized worldwide for this species: “red,” with red-purple tinged stems and pale pink to lilac flowers; and “green,” with fully green stems and white flowers—all “races” observed in Florida exhibiting the same growth habit. Ecological Significance: Introduced repeatedly to Florida waters since 1979, despite its state and federal listing as a prohibited plant and noxious weed (R. Kipker, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, unpublished data). Popular among some recent immigrants as a common potherb from the homeland (T. Q. Ngo, Vietnamese Community of Florida, Pinellas Park, 1995 personal communication), and has been studied in Florida as a vegetable crop (e.g., Bruemmer and Roe 1979, Snyder et al. -

Aquatic Vegetables

Aquatic Vegetables A.K. Pandey Principal Scientist Indian Institute ofVegetable Research Varanasi (India) ATPA Agrotech Publishing Academy UDAIPUR Published by : Mrs. Geeta Somani Agrotech Publishing Academy llA-Vinayak Complex B Durga Nursery Road Udaipur - 313 001 Mob. : 9414169635, 9413763031 Information contained in this book has been published by Agrotech Publishing Academy and has been obtained by its authors believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the publisher and its authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damage arising out of use of this information and specially disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Disputes if any, are subjected to Udaipur jurisdiction only. REPRlNThD 2014 First Edition 2011 © A uthors All rights reserved ISBN : (13) 978-81-8321-197-0 ISBN : (10) 81-8321-197-6 Printed at: Salasar Imaging Systems Delhi -110035 (India) Preface The country bestowed with the unique gift of nature having variable climates in one and another parts of the country coupled with very distinct seasons enable to produce an array of vegetables from seashore to snowline. Apart from rich diversity of terrestrial vegetables, the country is a natural abode of a number of aquatic veg etables thriving in water bodies viz., lakes, lagoons, ponds, ditches and marshy wet places. Besides India, China, Thailand, Vietnam, Japan and Malaysia are considered suitable niche of a number of nutritionally and medicinally rich aquatic vegetables. In India, a number of aquatic vegetables viz., water chest nut (Trapa spp.), water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica), lotus (Nelumbo nucifera), and watercress (Nastur tium aquaticum) are grown sporadically/commercially. -

Risk Assessment for Water Spinach (Ipomoea Aquatica) in Texas

J. Aquat. Plant Manage. 55: 96–102 Risk assessment for water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) in Texas EARL W. CHILTON II* ABSTRACT Although there is one report of 405 ha in Marengo County, Alabama, that report is in error and in fact there are no Water spinach (Ipomoea aquatica) is a member of the reports of water spinach in Alabama (P. Robbins, U.S. Army morning glory family (Convolvulaceae) that is native to Corps of Engineers Mobile District, pers. comm.). In the India and Southeast Asia but has been widely cultivated in United States, water spinach is cultivated in California, many tropical areas around the world. Despite initial Florida, Texas, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. In Asia, water predictions of potential invasiveness, water spinach appears spinach is known by many names including ong choy, to be a relatively low-risk species, even in the states where it swamp cabbage, ong tsoi, weng kai, kang kong (China and was most likely to establish such as Texas, Florida, and Taiwan), tra kuon (Cambodia), asagao na and yu sai (Japan), southern California. Risk analysis suggests that it is a very and rau muong (Vietnam). Austin (2007) provides a more low-risk species in Texas. After 20 to 30 yr of commercial complete list with more than 120 names and languages. production in California, Florida, and Texas, it is currently According to Cook (1990a) water spinach is usually a found outside of cultivation in only four counties in the perennial species but may occasionally become annual. The continental United States, and is easily controlled with stems typically grow as a trailing vine but can grow erect. -

In Vitro Anthelmintic Activity of Ipomea Aquatica

International Journal of Current Pharmaceutical Research ISSN- 0975-7066 Vol 10, Issue 3, 2018 Original Article IN VITRO ANTHELMINTIC ACTIVITY OF IPOMEA AQUATICA SRIKANTH I.*, KIRAN KUMAR V., KRISHNA SAI K., SUNITHA M., RAMANJANEYULU K., HIMABINDHU J. Department of Pharmacognosy, Vishnu Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, Narsapur, Medak Email: [email protected] Received: 22 Jan 2018, Revised and Accepted: 08 Apr 2018 ABSTRACT Objective: The present study was aimed at the evaluation of in vitro anthelmintic activity of ethanolic leaf extract of ipomeaaquatica against Indian earthworm Pheretimaposthuma. Methods: Four concentrations (25 mg/ml, 50 mg/ml, 75 mg/ml, 100 mg/ml) were tested and results were expressed in terms of time for paralysis and time of the death of worms. In this study, Albendazole was used as a standard drug. Results: Ethanolic leaf extract of ipomea aquatic showed significant activity at higher concentrations when compared to standard group (Albendazole). Conclusion: It can be concluded that the ethanolic leaf extract of Ipomeaaquaticahas shown more significant anthelmintic activity when compared to Albendazole against Indian earthworm Pheretimaposthuma. Keywords: Anthelmintic activity, ipomeaaquatica, Albendazole, Ethanolic extract, Pheretimaposthuma © 2018 The Authors. Published by Innovare Academic Sciences Pvt Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22159/ijcpr.2018v10i3.27338 INTRODUCTION shaped) to lanceolate, 5–15 cm (2–6 in) long and 2–8 cm (0.8–3 in) broad. The flowers are trumpet-shaped, 3–5 cm (1–2 in) in diameter, Helminthic infections are among the commonest infections in man, and usually white in colour with a mauve centre.