Let Us Know How Access to This Document Benefits You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moresurprisesfromfairacres

Fiction ISBN1-56145-255-6 $14.95 www.peachtree-online.com EFFIE LELAND WILDER’S ou’d think that author Effie Wilder—at the age of first novel, OUT TO PASTURE ninety-two and with more than 500,000 copies of her H, MY GOODNESS! Hattie (BUT NOT OVER THE HILL) was is at it again! In spite of her published to great acclaim in Yfour best-selling books in print—would be content to O 1995 when she was eighty-five rest on her laurels. Fortunately for us, she isn’t the “retiring” surprises fr failing eyesight, inveterate journal- years old. Its three sequels, OVER WHAT HILL, re om keeper and eavesdropper extraordi- sort. In response to the flood of letters from fans requesting o Fair cres) OLDER BUT WILDER, and ONE MORE TIME, have (m A naire Hattie McNair is still reporting attracted an even wider readership. another visit to FairAcres Home, Mrs. Wilder has graciously on the antics of her lovable cohorts at Mrs. Wilder has lived in Summerville, invited us back for another delightfully uplifting and enter- FairAcres Home. South Carolina, for more than sixty years, the In her familiar journal entries, last fifteen of them at the Presbyterian Home. taining adventure. Whether you’re already acquainted with Hattie takes note of the laughter that She graduated from Converse College in 1930 Hattie and her friends or are meeting them for the first time, lightens their days as well as the tears and received the Distinguished Alumna Award you’re sure to be charmed by these folks who have a whole lot in 1982. -

The Antarctic Sun, December 24, 2006

December 24, 2006 HowHow McMurdo Got Its Groove On Local music scene heats up By Peter Rejcek Sun staff OTHER RIFFS t’s possibly the cool- Even Shackleton got the est music scene on the blues, page 10 planet. McMurdo Station Pole, Palmer also jam, is certainly the hub page 11 Iof operations for the U.S. AntarcticI Program (USAP) wise, this is a real hotbed of with an austral summer popu- potential.” lation of a thousand people Fox is a pretty good judge or more. But in the last 10 or of what makes a music scene 15 years, it’s become a cross- pulse. He came of age dur- roads for musicians playing ing punk rock’s angry genesis in just about every genre in the late 1970s and early imaginable in their leisure 1980s, playing bass for the time, from reggae to rock and band United Mutation in the from blues to bluegrass. It’s Washington, D.C., area. (See a scene where a punk rocker the Dec. 18, 2005, issue of can share the night’s billing The Antarctic Sun at antarc- with a folk singer and a blues ticsun.usap.gov for a related guitarist – and the audience is story.) there to see them all. A conversation with Fox is “We have been really itself like listening to a punk lucky down here,” said Jay rock set – briefly intense out- Peter Rejcek / The Antarctic Sun Fox, the retail supervisor for bursts, each riff a variation Barb Propst plays guitar at the McMurdo Station Coffee House. -

Ephemeral Art Ephemeral Art

Apr–Jun 2008 The Magazine of the International Child Art Foundation Photo: Scott Whitelaw Photo Credit, opposite page: Christo and Jeanne-Claude: The Gates, Central Park, New York City, 1979–2005 April—June 2008 Volume 11, Issue 2, Number 38 Photo: Wolfgang Volz. © Christo and Jeanne-Claude Editor’s Corner Ephemeral Art Ephemeral Art .................................................. 4 5 Where the Sands Blow, Mandalas Go ............. 5 Modernity is the transient, the fleeting, the contingent; it is one half of art, the other being Ephemera in Art ............................................... 6 the eternal and the immovable. Ephemeral Art: Visualizing Time ...................... 8 - Charles Baudelaire (French Poet, 1857) Christo and Jeanne-Claude .......................... 10 Transformational Touching the Ephemeral Moment ................. 13 Dear Readers, Enviromental Art, Page 10 Art from Ice .................................................... 14 Lately it seems as though we are living in a constant state of transition in every corner of our planet. editor writers Interview with LEGO® Sculpture Artist .......... 16 14 Change is in the air; therefore, we have dedicated this Ashfaq Ishaq, Ph. D. Terry Barrett, Ph. D. B. Stephen Carpenter, II managing editor Day of the Dead: Día de Muertos .................. 18 distinctive issue of ChildArt to the Ephemeral Arts. Melissa Chapin Carrie Foix Andrew Crummy As you will soon discover, ephemeral artists “live in assistant editor Vicki Daiello Making Ephemeral Art ................................... 20 the moment.” From Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s B. Stephen Carpenter, II Claire Eike Sheri R. Klein, Ph. D. Clementina Ferrer How to Make a Paper Boat Sculpture ........... 22 environmental works (p.10) to the delicate sand Patricia McKee Carrie Foix Amanda Lichtenwalner Here Today, Gone Tomorrow ......................... 24 mandalas of Tibetan monks (p.5), ephemeral art’s contributing editor Joanna Mawdsley Amanda Lichtenwalner existence is shaped by the effects of time. -

Conceptual Blending, Metaphors, and the Construction Of

Conceptual Blending, Metaphors, and the Construction of Meaning in Ice Age Europe: An Inquiry Into the Viability of Applying Theories of Cognitive Science to Human History in Deep Time By Timothy Michael Gill A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Margaret Conkey, Chair Professor Rosemary Joyce Professor Kent Lightfoot Professor Eve Sweetser Fall 2010 Copyright Timothy Michael Gill, 2010 All rights reserved Abstract Conceptual Blending, Metaphors, and the Construction of Meaning in Ice Age Europe: An Inquiry Into the Viability of Applying Theories of Cognitive Science to Human History in Deep Time by Timothy Michael Gill Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Margaret Conkey, Chair Although the peoples of Ice Age Europe undoubtedly considered the drawings, engravings and other imagery created during that long period of prehistory to be deeply meaningful, it is difficult for people today to discern with any degree of accuracy or reliability what those meanings may have been. Grand theories of meaning have been proposed, criticized, and in some cases rejected. The development over the last few decades of modern cognitive science presents us with another angle of approach to this difficult problem. In this dissertation I review two related cognitive science theories, Conceptual Metaphor Theory and Conceptual Integration -

Burcham Beacon Volume 10 8Th Edition August 2017

Burcham Beacon Volume 10 8th Edition August 2017 Independence Day Celebration A record number of residents, families and staff attended the annual BBQ in celebration of Independence Day on Monday, July 3. The weather could not have been more perfect and the music from “The Clarksons” helped set the festive mood, even getting a large group out on the dance floor for the Chicken Dance! A special “Thank You” to the Hospitality Ser- vices Team for the delicious meal and to the Recreation Team for organizing the wonderful celebration. We look for- ward to the final celebration of the summer season with the Luau on Fri- day, September 1, to celebrate La- Just as in history, the light- bor Day. Be sure to save the date! house gave a guiding light to conduct mariners to their If you would like a table reserved destination, so will the for you and your family or a Burcham Beacon act as a guide to Aging with Grace. group of friends, please contact Kimber Lucius at 827-1061 or Alesha Williams 827-1068 by Fri- day, August 25. All non-reserved seating is first come, first serve. See more event photos on Page 16. I NSIDE T HIS I SSUE 3 Music & Enrichment 4 Employee Spotlights 5 Reminiscing 6 Special Events 7 Resident Center Happenings 8 CHR 2nd & 3rd floor Wellness Center Opens Neighborhoods 9 Places to Go with New Weekend Hours 10 Regular Program Descriptions 11/12 Wellness 13 Foundation The Fitness Team is excited to an- 14 Memorials 18 Spiritual Wellness nounce the Wellness Center is offi- & Support Groups 19 Movie Listings cially open for weekend hours. -

Heavier Than It Looks and Other Stories Matthew Obit As Ray

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2010 Heavier than it looks and other stories Matthew obiT as Ray Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Ray, Matthew Tobias, "Heavier than it looks and other stories" (2010). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 808. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HEAVIER THAN IT LOOKS AND OTHER STORIES A Thesis submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Matthew Tobias Ray Approved by Professor John Van Kirk, M.F.A., Committee Chairperson Dr. Rachael Peckham, M.F.A., Ph.D. Dr. Jane Hill, Ph.D. Marshall University May 2010 Keywords: third-person limited narration, first-person narration, second-person narration, metafiction, fatherlessness, suicide, violent crime, Appalachia, music, storytelling ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to extend my thanks to Professor John Van Kirk, Dr. Rachael Peckham, and Dr. Jane Hill. Without the patient consideration of each of these thoughtful people, this collection would not exist as it does today. Each member of my thesis committee helped me to see my writing from a different perspective and took the time to read the stories closely and provide me with excellent feedback. -

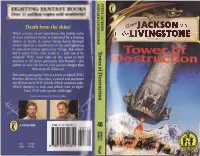

FF46 Tower O Destruction.Pdf

FIGHTING FANTASYBOO KIi Over 12 rnillion copiessold worldwldel ll o"o 4*LlVIIIGSTONE frF fr Puftrn Books TOWER OF DESTRUCTION Thirstingfor justice,you musl out on the L'ailof -5et the bizirre device.But wheredid it come From Mr'ho madeiL - and can it be sLopped?YOU must seeyour ouestthroueh to ils astoni+lngconclusion to ffnd the answersio il Lhesequestions. Eut beware - the sPhere is the key to a Fargreafer danger that threatensall Allansia! Two dice, a pencil and an eraser are all you n€ed to embark on this remarkable adventure, which comes complet with its elaboratecombat sysLem and a score sheetto ecordyour Progrcss. Many fearsomedangers lie aheadirnd successis by no meanscertain. Powe-rful adversaries are rahged against vou enemieswho wjll stop at nothing to foil you in vourquesr. lts up to YOU to decidewhich route Lo Follow,whi.h dangersto rish and which foesto fight Dare you takeup Lhechallenge? FightiflS Fant$y Gd Mbook Steve Jackson and Ian Living6tone PreEenr , THEFOREST OI DOOM rr DA€CEI5 Or DAX(N!S5 !Z BLACK!'EN PROPHECY 44 LECIM OF THE SIIADOW Martin Stev€Ja.ksnt SORCERYI Keith r (H,{Rl - cn-/PoRr or r&fs Iltuikatd W PeteKnifton FICI{TINC FANTASY lA€ r*ioducrory Role Playing Cde Th€ Adveea fighti$ FmtE y Sytle DUNCEONEER An Inhoduction to Advmed Fighhng Fantary BLACKsANDT - Mo,e Advmed Edtins Falasy OUI OF IHE PIT Fighting Fmtasy MonsteE TITAN The FighhnA lantasy wodd Th€ Fidting lebsy Novels THE TROLLTOOfi wAxS - ClEos lnvades All.nsia Pufffn Bmk6 DEMONSTEALER - Cladda Ddhnm€ Retms PUFfIN BOOKS CONTENTS Publded bY th€ Pcngum CrouP rval| ,rr^,'d E 'paeu,Bools.,J 'ws)- sldad Pqe IBoo" s'|. -

THE SNOW QUEEN a Fairytale in Seven Stories

THE SNOW QUEEN A fairytale in seven stories First story, which deals with the mirror and the shards of glass. Right then! Time to start. When we’re at the end of the story we’ll know more than we do now, for it has to do with an evil ogre! one of the very worst – it was ‘the devil’! One day he was in a really good mood, for he had made a mirror that had the property of reducing everything good and beautiful that was reflected in it into practically nothing, but whatever was fit for nothing and looked bad grew more pronounced and became even worse. The loveliest landscapes looked like boiled spinach in it, and the best of people turned ugly or stood on their heads with no stomach, their faces became so distorted that they were unrecognisable, and if someone had a freckle, you could be sure that it spread out over both nose and mouth. It was most amusing, ‘the devil’ said. If a good pious thought went through the mind of a person, a grin appeared in the mirror, so that the ogre devil had to laugh at his ingenious invention. Everyone who went to an ogre school – for he ran such a place – said far and wide that a miracle had taken place; now for the first time one could really see, they felt, what the world and people really looked like. They ran around with the mirror, and finally there wasn’t a country or a single person that had not been distorted in it. -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Touch and Go…Magazine (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Sex Master…Squeeze (7/78) Surrender…Cheap Trick (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) I Wanna Be Sedated (megamix)…The Ramones (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) I See Red…Split Enz (12/78) Roxanne…The -

Back Yard, February 15, 1999, Vol. IV, No. 61

Volume IV, Issue #61 February 15,1999 Ruth & Matt Launch SCHELL BROS CIRCUS, 1929 1930 •By CarCM. T)eVere, Sr. (From "For Our Eyes Only"*Published by Bud) I spent a lot of time on the road with my parents when they were agents. Dad hitched the trailer to our sedan at 9 or 10 o'clock each morning. The jumps from one town to another were normally less than a 100 miles. We usually arrived at the next town before noon. Dad found the circus lot, unhitched the trailer, & he and Mom went to work. Sometimes I remained in the trailer. Other times, I rode to town with them. Many times I played in the back set of the car while Mom spoke to a prospective customer in the front seat. She gave a pitch in her front seat office while I listened. I heard her repeat the talk so many times, I entertained my folks during a jump by giving her entire presentation. I played the part of my mother & that of the buyer. So my parents declared me a full-fledged banner salesman at age six. I felt big! We loved to sing in the car. I thought it sounded beautiful. My parents harmonized, & they tried to teach me. However, I was better in the lead. The only song I understood for harmony was "You Are My Sunshine." We sang it several times each day to give me a chance to shine. We played many road games. One was "Auto License Plate Alphabet." My favorite was a game Dad made up, called "Popular Cars." Each of us selected a brand of car to look for on the highway. -

Advanced Placement Literature and Composition Short Story Packet

Advanced Placement Literature and Composition Short Story Packet 2018-19 “The Masque of the Red Death” (1842) By Edgar Allan Poe ………………………………………………………………………………………………. page 1 “To Build a Fire” (1908) By Jack London …………………………………………………………………………………………………… page 4 “Sweat” (1926) By Zora Neale Hurston ………………………………………………………………………………………. page 12 “Hills Like White Elephants: (1927) By Ernest Hemingway ……………………………………………………………………………………….. page 20 “A Good Man Is Hard to find” (1953) By Flannery O’Connor ……………………………………………………………………………………..... page 23 “Cathedral” (1983) By Raymond Carver…………………………………………………………………………………….......... page 34 0 “The Masque of the Red Death” By Edgar Allan Poe THE "Red Death" had long devastated the country. No pestilence had ever been so fatal, or so hideous. Blood was its Avatar and its seal --the redness and the horror of blood. There were sharp pains, and sudden dizziness, and then profuse bleeding at the pores, with dissolution. The scarlet stains upon the body and especially upon the face of the victim, were the pest ban which shut him out from the aid and from the sympathy of his fellow-men. And the whole seizure, progress and termination of the disease, were the incidents of half an hour. But the Prince Prospero was happy and dauntless and sagacious. When his dominions were half depopulated, he summoned to his presence a thousand hale and light-hearted friends from among the knights and dames of his court, and with these retired to the deep seclusion of one of his castellated abbeys. This was an extensive and magnificent structure, the creation of the prince's own eccentric yet august taste. A strong and lofty wall girdled it in. This wall had gates of iron. -

The Ice Queen

The Ice Queen By Ernest Ingersoll THE ICE QUEEN. Chapter I. THROWN UPON THEIR OWN RESOURCES. The early dusk of a December day was fast changing into darkness as three of the young people with whose adventures this story is concerned trudged briskly homeward. The day was a bright one, and Aleck, the oldest, who was a skilled workman in the brass foundry, although scarcely eighteen years of age, had given himself a half-holiday in order to take Kate and The Youngster on a long skating expedition down to the lighthouse. Kate was his sister, two years younger than he, and The Youngster was a brother whose twelfth birthday this was. The little fellow never had had so much fun in one afternoon, he thought, and maintained stoutly that he scarcely felt tired at all. The ice had been in splendid condition, the day calm, but cloudy, so that their eyes had not ached, and they had been able to go far out upon the solidly frozen surface of the lake. "How far do you think we have skated to-day, Aleck?" asked The Youngster. "It's four miles from the lower bridge to the lighthouse," spoke up Kate, before Aleck could reply, "and four back. That makes eight miles, to begin with." "Yes," said Aleck, "and on top of that you must put—let me see—I should think, counting all our twists and turns, fully ten miles more. We were almost abreast of Stony Point when we were farthest out, and they say that's five miles long." "Altogether, then, we skated about eighteen miles." "Right, my boy; your arithmetic is your strong point." "Well, I should say his feet were his strong point to-day," Kate exclaimed, in admiration of her brother's hardihood.