By Joyce Carol Oates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senator Edward

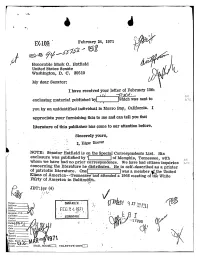

_ _ 7 _g__ ! 1 i 3 4 February24¢, 1971 'REG-#7-l5 7% HonorableC!. Mark Hateld W » United. States Senate Washington, D. C, 20510 M; My dear -Senator; » i I have receivedyogr letter of gebrllti1351 F be enclosingp11b1ished'by material to s* sent_ Ib"/C yon.by an unidentified inélividualin Morro;Bay,; ¬&.1if011I.119i-I appreciate your"furnishing thisto me.and0an1te11Y°u'th9~l? literatureof this publisher has come.to our attention before. , Sincerely you1$, i s ~ J, EdgaliHoover NOTE: SenatorHatfield ison the Specia17Cor_respo,n_dents-His List.' enclosure waspI1b1iSheClby !|:| of Memphis, Tennessee, with 106 V5-fh0m»have We had'no_ *corresponden prior _:~e.have We had oitizeninquiries ibvc cvonceroningthe" literaturehe distributes. He is self-described asai printer of patrioticliterature. Qne was membergj;a the United K;{§~nSAmerica--Tenne_ssee"and of attendeda 1966meeting oftiiaetWhite t Party of America in Baltimeie-. /it ' 92 Tolson __.______ JBT:.jsr ! . I P» " Sullivan ,>.¬_l."/ Zllohr a l 4 Bisl92op.___.ri Brennan. C.D. Callahan i_.. CaSPCT i__.____ Conrad .?__._____ ~ 1* t : *1 l ~ nalb<§y§f_,Iz__t'_I_t ,coMMFBI, 8T~2, it __~ _ at Felt " l , ......W_-»_-_-»_Qtg/<>i.l£Fa¥, .,¢ Gale Roseni___ Tavel _i___r Walters ____i__ Soyars ' Tole. Ronni l set 97l Holmes _ _ M Si andv ¬ * MAI_L~R0.01§/ll:_ TELETYPE UNII[:] 3* .7H, §M1'. 'Icls'>n.-_._.__ -K i»><':uRyM. JACKSON,WASH., CHAIRMAN~92 Q "1 MT Sullivan? c|_|rrro|'uANDERSON, P.Mac. N. sermon m_|_o 'v_o. -

Stories of Re-Reading: Inviting Students to Reflect on Their Emotional Responses to Fiction

The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning Volume 8 Winter 2002-2003 Article 6 2002 Stories of Re-Reading: Inviting Students to Reflect on Their Emotional Responses to Fiction Brenda Daly Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl Part of the Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Disability and Equity in Education Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Instructional Media Design Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Other Education Commons, Special Education and Teaching Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Daly, Brenda (2002) "Stories of Re-Reading: Inviting Students to Reflect on Their Emotional Responses ot Fiction," The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning: Vol. 8 , Article 6. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl/vol8/iss1/6 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl. Stories of Re-Reading: Inviting Students to Reflect on Their Emotional Responses to Fiction Cover Page Footnote Brenda Daly, professor of English at Iowa State University, published Authoring a Life as well as a number of autobiographical essays. She also published Lavish Self-Divisions: The Novels of Joyce Carol Oates, essays on women writers, and has co-edited Narrating Mothers. -

Joyce Carol Oates 16

JOYCE CAROL OATES 16. 6. 1938 Americká prozai čka, básní řka, dramati čka a kriti čka Joyce Carol Oatesová se narodila 16. června 1938 v dělnické rodin ě v Lockportu, ve stát ě New York. Její matka Carolina (rozená Bush) byla ženou v domácnosti, otec Frederic James Oates pracoval jako nástroja ř a konstruktér. Joyce byla nejstarší ze t ří d ětí – její bratr Fred junior se narodil v roce 1943 a sestra Lynn Ann v roce 1956 (je postižena autismem). Oatesová byla vychovávána jako katoli čka, nyní je ale ateistkou. D ětství prožila na rodinné farm ě svých prarodi čů nedaleko Erijského jezera blízko kanadských hranic (kraj Erie získal důležité místo v její románové i povídkové tvorb ě, kde ho nazývá „Eden County“). Velký vliv na ni měla babi čka z otcovy strany, Blanche Woodside, která byla vášnivou čtená řkou. Práv ě ona p řivedla Joyce k literatu ře (v ěnovala jí knihu Alenka v říši div ů od Lewise Carrolla, jež na ni hluboce zap ůsobila). Když ve svých čtrnácti letech dostala Joyce od babi čky psací stroj, za čala se v ěnovat psaní. Již v patnácti letech napsala sv ůj první román, vydavatelé ho však odmítli publikovat s tím, že je příliš depresivní. J. C. Oatesová chodila do stejné jednot řídky jako její matka. Poté navšt ěvovala v ětší p řím ěstské školy a následn ě studovala na st řední škole Williamsville South High School, kde pracovala pro školní noviny. Maturitní zkoušku složila v roce 1956. Díky tomu, že získala stipendium, za čala studovat angli čtinu na Syrakuské univerzit ě, kde absolvovala s vyznamenáním roku 1960. -

Throughout His Writing Career, Nelson Algren Was Fascinated by Criminality

RAGGED FIGURES: THE LUMPENPROLETARIAT IN NELSON ALGREN AND RALPH ELLISON by Nathaniel F. Mills A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Alan M. Wald, Chair Professor Marjorie Levinson Professor Patricia Smith Yaeger Associate Professor Megan L. Sweeney For graduate students on the left ii Acknowledgements Indebtedness is the overriding condition of scholarly production and my case is no exception. I‘d like to thank first John Callahan, Donn Zaretsky, and The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Charitable Trust for permission to quote from Ralph Ellison‘s archival material, and Donadio and Olson, Inc. for permission to quote from Nelson Algren‘s archive. Alan Wald‘s enthusiasm for the study of the American left made this project possible, and I have been guided at all turns by his knowledge of this area and his unlimited support for scholars trying, in their writing and in their professional lives, to negotiate scholarship with political commitment. Since my first semester in the Ph.D. program at Michigan, Marjorie Levinson has shaped my thinking about critical theory, Marxism, literature, and the basic protocols of literary criticism while providing me with the conceptual resources to develop my own academic identity. To Patricia Yaeger I owe above all the lesson that one can (and should) be conceptually rigorous without being opaque, and that the construction of one‘s sentences can complement the content of those sentences in productive ways. I see her own characteristic synthesis of stylistic and conceptual fluidity as a benchmark of criticism and theory and as inspiring example of conceptual creativity. -

The Proliferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nelson Algren

THE PROLIFERATION OF THE GROTESQUE IN FOUR NOVELS OF NELSON ALGREN by Barry Hamilton Maxwell B.A., University of Toronto, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department ot English ~- I - Barry Hamilton Maxwell 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : Barry Hamilton Maxwell DEGREE: M.A. English TITLE OF THESIS: The Pro1 iferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nel son A1 gren Examining Committee: Chai rman: Dr. Chin Banerjee Dr. Jerry Zaslove Senior Supervisor - Dr. Evan Alderson External Examiner Associate Professor, Centre for the Arts Date Approved: August 6, 1986 I l~cr'ct~ygr.<~nl lu Sinnri TI-~J.;~;University tile right to lend my t Ire., i6,, pr oJcc t .or ~~ti!r\Jc~tlcr,!;;ry (Ilw tit lc! of which is shown below) to uwr '. 01 thc Simon Frasor Univer-tiity Libr-ary, and to make partial or singlc copic:; orrly for such users or. in rcsponse to a reqclest from the , l i brtlry of rllly other i111i vitl.5 i ty, Or c:! her- educational i r\.;t i tu't ion, on its own t~l1.31f or for- ono of i.ts uwr s. I furthor agroe that permissior~ for niir l tipl c copy i rig of ,111i r; wl~r'k for .;c:tr~l;rr.l y purpose; may be grdnted hy ri,cs oi tiI of i Ittuli I t ir; ~lntlc:r-(;io~dtt\at' copy in<) 01. -

The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1979 The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates Kathleen Burke Bloom Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bloom, Kathleen Burke, "The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates" (1979). Master's Theses. 3012. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3012 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Kathleen Burke Bloom THE GROTESQUE IN THE FICTION OF JOYCE CAROL OATES by Kathleen Burke Bloom A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman, James E. Rocks, and the late Stanley Clayes for their encouragement and advice. Special thanks go to Professor Bernard P. McElroy for so generously sharing his views on the grotesque, yet remaining open to my own. Without the safe harbors provided by my family, Professor Jean Hitzeman, O.P., and Father John F. Fahey, M.A., S.T.D., this voyage into the contemporary American nightmare would not have been possible. -

THE TAKING of AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E

THE TAKING OF AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E. Sprague Richard E. Sprague 1976 Limited First Edition 1976 Revised Second Edition 1979 Updated Third Edition 1985 About the Author 2 Publisher's Word 3 Introduction 4 1. The Overview and the 1976 Election 5 2. The Power Control Group 8 3. You Can Fool the People 10 4. How It All BeganÐThe U-2 and the Bay of Pigs 18 5. The Assassination of John Kennedy 22 6. The Assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King and Lyndon B. Johnson's Withdrawal in 1968 34 7. The Control of the KennedysÐThreats & Chappaquiddick 37 8. 1972ÐMuskie, Wallace and McGovern 41 9. Control of the MediaÐ1967 to 1976 44 10. Techniques and Weapons and 100 Dead Conspirators and Witnesses 72 11. The Pardon and the Tapes 77 12. The Second Line of Defense and Cover-Ups in 1975-1976 84 13. The 1976 Election and Conspiracy Fever 88 14. Congress and the People 90 15. The Select Committee on Assassinations, The Intelligence Community and The News Media 93 16. 1984 Here We ComeÐ 110 17. The Final Cover-Up: How The CIA Controlled The House Select Committee on Assassinations 122 Appendix 133 -2- About the Author Richard E. Sprague is a pioneer in the ®eld of electronic computers and a leading American authority on Electronic Funds Transfer Systems (EFTS). Receiving his BSEE degreee from Purdue University in 1942, his computing career began when he was employed as an engineer for the computer group at Northrup Aircraft. He co-founded the Computer Research Corporation of Hawthorne, California in 1950, and by 1953, serving as Vice President of Sales, the company had sold more computers than any competitor. -

Raven Leilani the Novelist Makes a Shining Debut with Luster, a Mesmerizing Story of Race, Sex, and Power P

Featuring 417 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 15 | 1 AUGUST 2020 REVIEWS Raven Leilani The novelist makes a shining debut with Luster, a mesmerizing story of race, sex, and power p. 14 Also in the issue: Raquel Vasquez Gilliland, Rebecca Giggs, Adrian Tomine, and more from the editor’s desk: The Dysfunctional Family Sweepstakes Chairman BY TOM BEER HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As this issue went to press, the nation was riveted by the publication of To o Chief Executive Officer Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man MEG LABORDE KUEHN (Simon & Schuster, July 14), the scathing family memoir by the president’s niece. [email protected] Editor-in-Chief For the past four years, nearly every inhabitant of the planet has been affected TOM BEER by Donald Trump, from the impact of Trump administration policies—on [email protected] Vice President of Marketing climate change, immigration, policing, and more—to the continuous feed of SARAH KALINA Trump-related news that we never seem to escape. Now, thanks to Mary Trump, [email protected] Ph.D., a clinical psychologist, we understand the impact of Donald Trump up Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU close, on his family members. [email protected] It’s not a pretty picture. Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK The book describes the Trumps as a clan headed by a “high-functioning [email protected] Tom Beer sociopath,” patriarch Fred Trump Sr., father to Donald and the author’s own Young Readers’ Editor VICKY SMITH father, Fred Jr. -

Alice in Zombieland SUMMARY

Alice in Zombieland Gena Showalter Harlequin Enterprises Limited, 2012 404 pages SUMMARY: After a car crash kills her parents and younger sister, sixteen year old Alice Bell learns that her dad was right. The monsters are real. Now, Ali must learn to fight the monsters in order to stay alive. IF YOU LIKED THIS BOOK TRY… Wake, Lisa McMann Through the Zombie Glass, Gena Showalter Infinity, Sherrilyn Kenyon School Spirits, Rachel Hawkins WEBSITES: White Rabbit Chronicles, http://www.wrchronicles.com Official website of Gena Showalter, http://genashowalter.com BOOKTALK: Disclaimer: If (because of the book’s title) you are expecting a re-telling of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, you will be disappointed. However, don’t let that stop you from picking up this book. It’s a great read with a different twist on the whole Zombie concept. Yes, there are zombies in the book, but they’re not your typical zombies. Instead of being undead humans that crave human flesh, Showalter’s zombies are really infected spirits that eat the spirits of humans which then causes the humans to become infected. Not everyone can see the zombies. Sixteen year old Alice Bell doesn’t see them until after a car crash that kills her parents and younger sister. Alice moves in with her grandparents and attend a different high school. At her new school, Ali hooks up with a group of kids who turn out to be zombie slayers. Cole, the leader of the group, just happens to be the most gorgeous “bad boy” that Ali has ever seen. -

Cassette Books, CMLS,P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 319 210 EC 230 900 TITLE Cassette ,looks. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 8E) NOTE 422p. AVAILABLE FROMCassette Books, CMLS,P.O. Box 9150, M(tabourne, FL 32902-9150. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) --- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Audiotape Recordings; *Blindness; Books; *Physical Disabilities; Secondary Education; *Talking Books ABSTRACT This catalog lists cassette books produced by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped during 1989. Books are listed alphabetically within subject categories ander nonfiction and fiction headings. Nonfiction categories include: animals and wildlife, the arts, bestsellers, biography, blindness and physical handicaps, business andeconomics, career and job training, communication arts, consumerism, cooking and food, crime, diet and nutrition, education, government and politics, hobbies, humor, journalism and the media, literature, marriage and family, medicine and health, music, occult, philosophy, poetry, psychology, religion and inspiration, science and technology, social science, space, sports and recreation, stage and screen, traveland adventure, United States history, war, the West, women, and world history. Fiction categories includer adventure, bestsellers, classics, contemporary fiction, detective and mystery, espionage, family, fantasy, gothic, historical fiction, -

1 Semiotics Analysis on Fantastic Beast and Where

SEMIOTICS ANALYSIS ON FANTASTIC BEAST AND WHERE TO FIND THEM NOVEL BY JK ROWLING’S PROPOSAL Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirement For The Degree of Sarjana Pendidikan (S.Pd) English Education Program By : DICKY INDRAWAN NPM 1602050102 FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY MUHAMMADIYAH SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2021 1 1 2 ABSTRACT DICKY INDRAWAN, Semiotics Analysis On Fantastic Beast and Where To Find Them Novel By J.K Rowling. This thesis is a research about analysis semiotic in the Novel “Fantastic Beast and Where to Find Them” By J.K Rowling. The objective of this research are (1) To know the interpretation of signifier and signified in the Novel Fantastic Beast and Where to Find Them by J.K Rowling (2) To know the meaning of Fantastic Beast and Where to Find Them in novel by semiotic approach. The method used in this research is qualitative method. The object of this research used both formal and material object. Formally, this research used semiotic by using Rolland Barthes theory. Materially, this research used the novel Fantastic Beast and Where to Find Them by J.K Rowling which was published in 2001 and some books was used to analyze and supported this research. In collecting the data, the writer used note taking as instrument. The writer used Rolland Barthes‟s theory to analysis semiotic in the Novel “Fantastic Beast and Where to Find Them” By J.K Rowling. In this research, the writer found there were two part of semiotic theory found in the novel “Fantastic Beast and Where to Find Them” by J.K Rowling there are signifier and signified. -

A Novel That Demands the Most Literal

BIBLIOTECA TECLA SALA March 19, 2020 The Man Without a Shadow Joyce Carol Oates « A novel that demands the most literal interpretation of the definition “psychological thriller”, The Man Without a Shadow showcases Oates’s grasp of the complexities of the human psyche Contents: via an enticing combination Introduction 1 of the ambiguity of Memento Author biography 2-3 New York Times 4-5 and the poignant realism book review “People think I 6-8 of Awakenings. write quickly but I actually don’t” » Notes 9 [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/feb/21/the-man-without-a- shadow-joyce-carol-oates-review] Page 2 Author biography wrote her first novel, though it Oates's first novel, With was rejected by publishers who Shuddering Fall (1964), shows her found its subject matter, which interest in evil and violence in the concerned the rehabilitation (the story of a romance between a restoring to a useful state) of a teenage girl and a thirty-year-old drug addict, too depressing for stock car driver that ends with teenage audiences. After high his death in an accident. Oates's school Oates won a scholarship best-known early novels form a to Syracuse University, where trilogy (three-volume work) she studied English. Before her exploring three different parts of senior year she was the co- American society. The first, A winner of a fiction contest Garden of Earthly Delights (1967), sponsored tells the story of the daughter of by Mademoiselle magazine. After a migrant worker who marries a graduating at the top of her class wealthy farmer in order to in 1960, Oates enrolled in provide for her illegitimate One of the United States's graduate school at the University (having unmarried parents) son.