Joyce Carol Oates and Food David Rutledge University of New Orleans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall2011.Pdf

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta Fall 201 1 NOW AVAILABLE Complete and updated coverage by The New York Times about WikiLeaks and their controversial release of diplomatic cables and war logs OPEN SECRETS WikiLeaks, War, and American Diplomacy The New York Times Introduction by Bill Keller • Essential, unparalleled coverage A New York Times Best Seller from the expert writers at The New York Times on the hundreds he controversial antisecrecy organization WikiLeaks, led by Julian of thousands of confidential Assange, made headlines around the world when it released hundreds of documents revealed by WikiLeaks thousands of classified U.S. government documents in 2010. Allowed • Open Secrets also contains a T fascinating selection of original advance access, The New York Times sorted, searched, and analyzed these secret cables and war logs archives, placed them in context, and played a crucial role in breaking the WikiLeaks story. • online promotion at Open Secrets, originally published as an e-book, is the essential collection www.nytimes.com/opensecrets of the Times’s expert reporting and analysis, as well as the definitive chronicle of the documents’ release and the controversy that ensued. An introduction by Times executive editor, Bill Keller, details the paper’s cloak-and-dagger “We may look back at the war logs as relationship with a difficult source. Extended profiles of Assange and Bradley a herald of the end of America’s Manning, the Army private suspected of being his source, offer keen insight engagement in Afghanistan, just as into the main players. Collected news stories offer a broad and deep view into the Pentagon Papers are now a Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the messy challenges facing American power milestone in our slo-mo exit from in Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. -

The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1979 The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates Kathleen Burke Bloom Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bloom, Kathleen Burke, "The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates" (1979). Master's Theses. 3012. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3012 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Kathleen Burke Bloom THE GROTESQUE IN THE FICTION OF JOYCE CAROL OATES by Kathleen Burke Bloom A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman, James E. Rocks, and the late Stanley Clayes for their encouragement and advice. Special thanks go to Professor Bernard P. McElroy for so generously sharing his views on the grotesque, yet remaining open to my own. Without the safe harbors provided by my family, Professor Jean Hitzeman, O.P., and Father John F. Fahey, M.A., S.T.D., this voyage into the contemporary American nightmare would not have been possible. -

Novels for Years 9-10

NOVELS FOR YEARS 9-10 TWO PEARLS OF WISDOM ALISON GOODMAN 9780732288006 Eon is a potential Dragoneye, able to manipulate wind and water to nurture and protect the land. But Eon also has a dark secret. He is really Eona, found by a power–hungry master of the Dragon Magic in a search for the new Dragoneye. Because females are forbidden to practise the Art, Eona endures years of study concealed as a boy. Eona becomes Eon, and a dangerous gamble is put into play. Eon's unprecedented display of skill at the Dragoneye ceremony places him in the centre of a power struggle between the Emperor and his High Lord brother. The Emperor immediately summons Eon to court to protect his son and heir. Quickly learning to navigate the treacher- ous court politics, Eon makes some unexpected alliances, and a deadly enemy in a Dragoneye turned traitor. Based on the ancient lores of Chinese astrology and Feng Shui, The Two Pearls of Wisdom and its sequel The Neck- lace of the Gods are compelling novels set in a world filled with identities, dangerous politics and sexual intrigue. *TEACHING NOTES SINGING THE DOGSTAR BLUES ALISON GOODMAN 9780732288631 Since an alien selected her to be his time–travelling partner, Joss has met an assassin, con- fronted an anti–alien lobby and had her freewheeling lifestyle nipped in the bud by the high security that surrounds the first Chorian to study on Earth! But life with Mavkel is not really that bad, especially considering harmonica–playing Joss is fascinated by Chorians – a harmonising species who communicate through song. -

Celestial Timepiece: Randy Souther Interviewed by Caroline Marquette and Tanya Tromble-Giraud Randy Souther University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Gleeson Library Librarians Research Gleeson Library | Geschke Center 2017 Celestial Timepiece: Randy Souther Interviewed by Caroline Marquette and Tanya Tromble-Giraud Randy Souther University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/librarian Part of the Digital Humanities Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Souther, Randy, "Celestial Timepiece: Randy Souther Interviewed by Caroline Marquette and Tanya Tromble-Giraud" (2017). Gleeson Library Librarians Research. 11. http://repository.usfca.edu/librarian/11 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Gleeson Library | Geschke Center at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gleeson Library Librarians Research by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Celestial Timepiece: Randy Souther Interviewed by Caroline Marquette and Tanya Tromble-Giraud Part 1 Would you introduce yourself? I’m the Head of Reference and Research Services at the University of San Francisco’s Gleeson Library, where I’ve worked for 25 years. Since 1995 I’ve run a website devoted to Joyce Carol Oates’s work, and in 2014 I started a scholarly journal on her work. How would you describe your involvement with Joyce Carol Oates’s work? My involvement with JCO’s work is ultimately personal. My interest in her work has informed some of my professional librarian activities over the years (bibliography, website design, editing), but it is likely that I would have spent much less time in these areas had not my personal interest and admiration of her work led me to them. -

Book Club in a Box TITLES AVAILABLE – NOVEMBER 2019 (Please Destroy All Previous Lists)

49-99 Book Club in a Box TITLES AVAILABLE – NOVEMBER 2019 (Please destroy all previous lists) FICTION, CONTEMPORARY AND HISTORICAL After You – by JoJo Moyes – (352 p.) – 15 copies Moyes’ sequel to her bestselling Me Before You (2012)—which was about Louisa, a young caregiver who falls in love with her quadriplegic charge, Will, and then loses him when he chooses suicide over a life of constant pain— examines the effects of a loved one’s death on those left behind to mourn. It's been 18 months since Will’s death, and Louisa is still grieving. After falling off her apartment roof terrace in a drunken state, she momentarily fears she’ll end up paralyzed herself, but Sam, the paramedic who treats her, does a great job—and she's lucky. Louisa convalesces in the bosom of her family in the village of Stortfold. When Louisa returns to London, a troubled 16- year-old named Lily turns up on her doorstep saying Will was her father though he never knew it because her mother thought he was "a selfish arsehole" and never told him she was pregnant. (Abbreviated from Kirkus) The Alchemist – by Paulo Coehlo – (186 p.) – 15 copies + Large Print "The boy's name was Santiago," it begins; Santiago is well educated and had intended to be a priest. But a desire for travel, to see every part of his native Spain, prompted him to become a shepherd instead. He's contented. But then twice he dreams about hidden treasure, and a seer tells him to follow the dream's instructions: go to Egypt to the pyramids, where he will find a treasure. -

Alice in Zombieland SUMMARY

Alice in Zombieland Gena Showalter Harlequin Enterprises Limited, 2012 404 pages SUMMARY: After a car crash kills her parents and younger sister, sixteen year old Alice Bell learns that her dad was right. The monsters are real. Now, Ali must learn to fight the monsters in order to stay alive. IF YOU LIKED THIS BOOK TRY… Wake, Lisa McMann Through the Zombie Glass, Gena Showalter Infinity, Sherrilyn Kenyon School Spirits, Rachel Hawkins WEBSITES: White Rabbit Chronicles, http://www.wrchronicles.com Official website of Gena Showalter, http://genashowalter.com BOOKTALK: Disclaimer: If (because of the book’s title) you are expecting a re-telling of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, you will be disappointed. However, don’t let that stop you from picking up this book. It’s a great read with a different twist on the whole Zombie concept. Yes, there are zombies in the book, but they’re not your typical zombies. Instead of being undead humans that crave human flesh, Showalter’s zombies are really infected spirits that eat the spirits of humans which then causes the humans to become infected. Not everyone can see the zombies. Sixteen year old Alice Bell doesn’t see them until after a car crash that kills her parents and younger sister. Alice moves in with her grandparents and attend a different high school. At her new school, Ali hooks up with a group of kids who turn out to be zombie slayers. Cole, the leader of the group, just happens to be the most gorgeous “bad boy” that Ali has ever seen. -

Book Group to Go Book Group Kit Collection Glendale Public Library

Book Group To Go Book Group Kit Collection Glendale Public Library Titles in the Collection—Spring 2015 Book Group Kits can be checked out for 8 weeks and cannot be placed on hold or renewed. To reserve a kit, please contact: [email protected] or call 818.548.2041 The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie In his first book for young adults, bestselling author Sherman Alexie tells the story of Junior, a budding cartoonist growing up on the Spokane Indian Reservation. Determined to take his future into his own hands, Junior leaves his troubled school on the rez to attend an all-white farm town high school where the only other Indian is the school mascot. Heartbreaking, funny, and beautifully written, the book chronicles the contemporary adolescence of one Native American boy. Poignant drawings by acclaimed artist Ellen Forney reflect Junior’s art. 2007 National Book Award winner. Fiction. Young Adult. 229 pages The Abstinence Teacher by Tom Perrotta A controversy on the soccer field pushes Ruth Ramsey, the human sexuality teacher at the local high school, and Tim Mason, a member of an evangelical Christian church that doesn't approve of Ruth's style of teaching, to actually talk to each other. Adversaries in a small-town culture war, they are forced to take each other at something other than face value. Fiction. 358 pages The Age of Miracles by Karen Thompson Walker On a seemingly ordinary Saturday in a California suburb, Julia and her family awake to discover, along with the rest of the world, that the rotation of the earth has suddenly begun to slow. -

Representations of Female Violence and Aggression in Joyce Carol O

ABSTRACT WEISSBERG, SARAH BUKER. In the Shadow of the Vamp: Representations of Female Violence and Aggression in Joyce Carol Oates’s Fiction. (Under the direction of Barbara Bennett.) Recently, feminist scholars have become interested in demystifying female initiated aggression and violence and in examining how women experience, express, and understand their own aggression. This study considers how author Joyce Carol Oates has contributed to that particular line of inquiry by publishing four specific short stories: “The Vampire,” “Lover,” “Gun Love,” and “Secret, Silent.” Chapter 1 of this thesis defines the archetype of the Lethal Woman, an archetype which embodies negative cultural conceptions of female violence and aggression. This chapter identifies Lethal Women figures from folklore, fiction, and film throughout the ages and then examines “The Vampire,” a story in which Oates exposes the sexism and androcentric motives behind the ongoing creation and reinforcement of the Lethal Woman archetype. Chapter 2 focuses on the stories “Lover,” “Gun Love,” and “Secret, Silent” and discusses how in these works, Oates explores the psychological impulses behind female initiated violence, passive aggression, and other subversive methods utilized by women for handling their aggression. This second chapter also contrasts Oates’s depictions of female violence/aggression against depictions of female violence/aggression in the contemporary popular media and concludes that Oates’s stories offer a refreshingly realistic alternative to historical and contemporary Lethal Woman narratives. In the Shadow of the Vamp: Representations of Female Violence and Aggression in Joyce Carol Oates’s Fiction by Sarah Buker Weissberg A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts ENGLISH Raleigh 2005 APPROVED BY: _________________________________ ________________________________ Dr. -

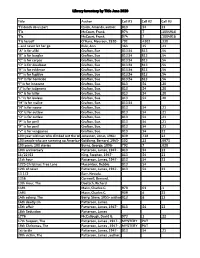

Library Inventory by Title June 2020 Title Author Call

Library Inventory by Title June 2020 Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Call #3 'Til death do us part Quick, Amanda, author. 813 .54 23 'Tis McCourt, Frank. 974 .7 .1004916 'Tis McCourt, Frank. 974 .7 .1004916 'Tis herself O'Hara, Maureen, 1920- 791 .4302 .330 --and never let her go Rule, Ann. 364 .15 .23 "A" is for alibi Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "B" is for burglar Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "C" is for corpse Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "D" is for deadbeat Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "E" is for evidence Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "F" is for fugitive Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "H" is for homicide Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "I" is for innocent Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "J" is for judgment Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "K" is for killer Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "L" is for lawless Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "M" is for malice Grafton, Sue. 813.54 "N" is for noose Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "P" is for peril Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "P" is for peril Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "V" is for vengeance Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 22 100-year-old man who climbed out the windowJonasson, and disappeared, Jonas, 1961- The 839 .738 23 100 people who are screwing up America--andGoldberg, Al Franken Bernard, is #3 1945- 302 .23 .0973 100 years, 100 stories Burns, George, 1896- 792 .7 .028 10th anniversary Patterson, James, 1947- 813 .54 22 11/22/63 King, Stephen, 1947- 813 .54 23 11th hour Patterson, James, 1947- 813 .54 23 1225 Christmas Tree Lane Macomber, Debbie 813 .54 12th of never Patterson, James, 1947- 813 .54 23 13 1/2 Barr, Nevada. -

I SOUTHERN MONSTERS in SOUTHERN SPACES

i SOUTHERN MONSTERS IN SOUTHERN SPACES: TRANSNATIONAL ENGAGEMENTS IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION by CHRISTEN ELIZABETH HAMMOCK (Under the Direction of JOHN LOWE) ABSTRACT Vampires, zombies, and other monsters have long been written about as a narrative space to work through collective anxieties, and the latest incarnation of these paranormal stories is no exception. What is remarkable is that many of these stories have adopted a Southern setting to explore Otherness. In this thesis, I seek to explore the role that Southern milieus plays in three television shows: The Walking Dead, True Blood, and Dexter. These shows are deeply invested in the culture and history of different “Souths,” ranging from the “Old South” of rural Georgia to a new, transnational South in Miami, Florida. I argue that this trend stems from the South’s hybrid existence as both colonizer and colonized, master and slave, and that a nuanced engagement with various Souths presents a narrative space of potential healing and rehabilitation. INDEX WORDS: Vampires; Zombies; Dexter; The Walking Dead; True Blood; Transnational; Southern literature; Television; U.S. South i SOUTHERN MONSTERS IN SOUTHERN SPACES: TRANSNATIONAL ENGAGEMENTS IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION by CHRISTEN ELIZABETH HAMMOCK A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2014 ii © 2014 Christen Elizabeth Hammock All Rights Reserved iii SOUTHERN MONSTERS IN SOUTHERN SPACES: TRANSNATIONAL ENGAGEMENTS -

American Fiction Since 1984

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts ETHICS AND URBAN REALITIES: AMERICAN FICTION SINCE 1984 A Dissertation in English by Sean Moiles © 2011 Sean Moiles Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2011 ii The dissertation of Sean Moiles was reviewed and approved* by the following: Kathryn Hume Edwin Earle Sparks Professor of English Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Michael Bérubé Paterno Family Professor in Literature Aldon Nielsen George and Kelly Professor in American Literature Tina Chen Associate Professor of English and Asian American Studies Philip Jenkins Edwin Earle Sparks Professor of the Humanities Mark Morrison Professor of English Department Head *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT ETHICS AND URBAN REALITIES: AMERICAN FICTION SINCE 1984 When critics and reviewers praise contemporary urban films and television productions, they often do so by comparing these texts to 19th-century realist and naturalist urban novels. David Simon’s HBO series The Wire, for example, has been lauded for its similarities to Dickens’s multilayered and realist vision of London. Unfortunately, these commentaries usually fail to acknowledge developments in contemporary U.S. urban fiction, perhaps in no small degree because much of this fiction explores the experiences of people from a variety of ethnic backgrounds. Ethics and Urban Realities challenges general assumptions about the state of U.S. urban fiction implied in commentaries on The Wire and made more overt in essays such as Tom Wolfe’s “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast: A Literary Manifesto for the New Social Novel” in which Wolfe blames poststructuralism for the supposed death of the urban novel. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value ---------------------------------- -------------------- ------- ------ 12 Again Sue Corbett 4.9 8 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and James Howe 5 9 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Tim Cooke 6.1 1 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10 28 2010: Odyssey Two Arthur C. Clarke 7.8 13 3 NBs of Julian Drew James M. Deem 3.6 5 3001: The Final Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 8.3 9 47 Walter Mosley 5.3 8 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 The A.B.C. Murders Agatha Christie 6.1 9 Abandoned Puppy Emily Costello 4.1 3 Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15 Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6 The Abduction Mette Newth 6 8 Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6 Abhorsen Garth Nix 6.6 16 Abigail Adams: A Revolutionary W Jacqueline Ching 8.1 2 About Face June Rae Wood 4.6 9 Above the Veil Garth Nix 5.3 7 Abraham Lincoln: Friend of the P Clara Ingram Judso 7.3 7 N Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to E.B. Phillips 8 4 N Absolute Brightness James Lecesne 6.5 15 Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7 N The Absolutely True Diary of a P Sherman Alexie 4 6 N An Abundance of Katherines John Green 5.6 10 Acceleration Graham McNamee 4.4 7 An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11 N Accidental Love Gary Soto 4.8 5 Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3 Achingly Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 4.9 4 The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2 Acorna: The Unicorn Girl