Representations of Female Violence and Aggression in Joyce Carol O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1979 The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates Kathleen Burke Bloom Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bloom, Kathleen Burke, "The Grotesque in the Fiction of Joyce Carol Oates" (1979). Master's Theses. 3012. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3012 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Kathleen Burke Bloom THE GROTESQUE IN THE FICTION OF JOYCE CAROL OATES by Kathleen Burke Bloom A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professors Thomas R. Gorman, James E. Rocks, and the late Stanley Clayes for their encouragement and advice. Special thanks go to Professor Bernard P. McElroy for so generously sharing his views on the grotesque, yet remaining open to my own. Without the safe harbors provided by my family, Professor Jean Hitzeman, O.P., and Father John F. Fahey, M.A., S.T.D., this voyage into the contemporary American nightmare would not have been possible. -

Released 26Th July 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS MAY170038 BANKSHOT #2 MAY170025 BLACK HAMMER #11 MAIN ORMSTON CVR MAY170026 BLACK HAMM

Released 26th July 2017 DARK HORSE COMICS MAY170038 BANKSHOT #2 MAY170025 BLACK HAMMER #11 MAIN ORMSTON CVR MAY170026 BLACK HAMMER #11 VAR LEMIRE MAR170044 BLACK SINISTER HC MAY170066 BPRD DEVIL YOU KNOW #1 MAY170067 BPRD DEVIL YOU KNOW #1 MIGNOLA VAR APR170101 CONAN THE SLAYER #11 NOV160071 HOW TO WIN AT LIFE BY CHEATING AT EVERYTHING TP MAY170068 JOE GOLEM OCCULT DETECTIVE OUTER DARK #3 FEB170063 LEGEND OF KORRA TP VOL 01 TURF WARS PT 1 MAY170023 MASS EFFECT DISCOVERY #3 MAY170024 MASS EFFECT DISCOVERY #3 NIEMCZYK VAR MAY170028 REBELS THESE FREE & INDEPENDENT STATES #5 (OF 8) MAR170077 SERENITY HC VOL 05 NO POWER IN THE VERSE MAR170064 USAGI YOJIMBO SAGA LEGENDS LTD ED HC MAR170063 USAGI YOJIMBO SAGA LEGENDS TP DC COMICS MAY170198 ACTION COMICS #984 MAY170199 ACTION COMICS #984 VAR ED MAY170200 ALL STAR BATMAN #12 MAY170201 ALL STAR BATMAN #12 ALBUQUERQUE VAR ED MAY170202 ALL STAR BATMAN #12 FIUMARA VAR ED APR170417 AQUAMAN KINGDOM LOST TP MAY170205 BATGIRL #13 MAY170206 BATGIRL #13 VAR ED MAY170209 BATMAN BEYOND #10 MAY170210 BATMAN BEYOND #10 VAR ED APR170437 BATMAN SUPERMAN WONDER WOMAN TRINITY TP NEW EDITION MAY170290 BATMAN THE SHADOW #4 (OF 6) MAY170292 BATMAN THE SHADOW #4 (OF 6) EPTING VAR ED MAY170291 BATMAN THE SHADOW #4 (OF 6) SALE VAR ED MAY170217 BLUE BEETLE #11 MAY170218 BLUE BEETLE #11 VAR ED JAN170426 DC DESIGNER SER WONDER WOMAN BY ADAM HUGHES STATUE (RES) MAY170225 DETECTIVE COMICS #961 MAY170226 DETECTIVE COMICS #961 VAR ED MAY170314 DOOM PATROL #7 (RES) MAY170315 DOOM PATROL #7 VAR ED (RES) MAY170229 FLASH #27 MAY170230 -

Novels for Years 9-10

NOVELS FOR YEARS 9-10 TWO PEARLS OF WISDOM ALISON GOODMAN 9780732288006 Eon is a potential Dragoneye, able to manipulate wind and water to nurture and protect the land. But Eon also has a dark secret. He is really Eona, found by a power–hungry master of the Dragon Magic in a search for the new Dragoneye. Because females are forbidden to practise the Art, Eona endures years of study concealed as a boy. Eona becomes Eon, and a dangerous gamble is put into play. Eon's unprecedented display of skill at the Dragoneye ceremony places him in the centre of a power struggle between the Emperor and his High Lord brother. The Emperor immediately summons Eon to court to protect his son and heir. Quickly learning to navigate the treacher- ous court politics, Eon makes some unexpected alliances, and a deadly enemy in a Dragoneye turned traitor. Based on the ancient lores of Chinese astrology and Feng Shui, The Two Pearls of Wisdom and its sequel The Neck- lace of the Gods are compelling novels set in a world filled with identities, dangerous politics and sexual intrigue. *TEACHING NOTES SINGING THE DOGSTAR BLUES ALISON GOODMAN 9780732288631 Since an alien selected her to be his time–travelling partner, Joss has met an assassin, con- fronted an anti–alien lobby and had her freewheeling lifestyle nipped in the bud by the high security that surrounds the first Chorian to study on Earth! But life with Mavkel is not really that bad, especially considering harmonica–playing Joss is fascinated by Chorians – a harmonising species who communicate through song. -

Algernon Charles Swinburne

A LGE R N O N C H A RLE S SWINBURNE A CRITICAL STUDY BY E DWARD THOMAS NEW YO RK MITCH ELL KE NNE R LE Y MCM" II To WALTE R DE LA MARE ’ ti z r t an i . Ques ons, 0 roy al trave ller, are eas e h auswe s - THE THREE MULLA M ULGAB S. N O T E T I AM very much indebted to Mr . heodore Watts - D a nton for permission to quote from i ’ t Sw nburne s prose and poe ry in this book , f for and to my friend , Mr . Clif ord Bax , many consultations . E . T . CONTENTS CHAPTE R PAGE I T T I C YDO . A ALAN A N AL N II . PREPARATIONS H III . THE APPRO AC I V PO MS AND B DS . E ALLA V OPI IO S : PROS -W ORKS . N N E B F U VI . SONGS E ORE S NRISE T R PO MS CH R T RISTI S VII . LA E E A AC E C VIII . LATER POEMS RE SULTS TRISTR M OFLY NE I" . A O SSE THE PLAYS ATALANTA I N CALYDO N ’ I T was the age of Browning s Dramatis Persona ’ ’ D of L andor s William Morris s efence Guenevere , ’ T of Heroic Idylls , ennyson s Idylls the King , ’ L ’ Meredith s Modern ove , Robert Buchanan s L P : L A ondon oems ongfellow , lexander Smith and Owen Meredith were great men . The The year 1 8 64 arrived . poetical atmo ” P sphere was exhausted and heavy, says rofessor “ Mackail of , like that a sultry afternoon darken f to . -

The Father-Wound in Folklore: a Critique of Mitscherlich, Bly, and Their Followers Hal W

Walden University ScholarWorks Frank Dilley Award for Outstanding Doctoral Study University Awards 1996 The father-wound in folklore: A critique of Mitscherlich, Bly, and their followers Hal W. Lanse Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dilley This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the University Awards at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Frank Dilley Award for Outstanding Doctoral Study by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Lilith: Gooddess of Sitra Ahra

Lilith: Goddess of Sitra Ahra Black Tower Publishing © Black Tower Publishing 2015 LILITH: GODDESS OF SITRA AHRA Second Edition Design & Layout: Black Tower Publishing Website: www.blacktowerpublishing.com Contact: [email protected] Black Tower Publishing © 2015 The materials contained here may not be reproduced or published in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without written permission from the authors. Individual contributors retain copyright of their essays and artwork. Content Foreward Ama Lilith -Daemon Barzai- Arachnid Lilith -Salomelihecatel- The Legacy of Lilith -Frater Nephilim- BINAH -David ‘Eosphorus’ Maples- Opening The Eye Of Lilith -Edgar Kerval- The Red Serpent -Frater G.S- The Abode of the Dark Mother -Walter García- The Huluppu Tree -Frater G.S- Lilith - The Night Hag -Pairika - Eva Borowska- The Witch of the Night -Daemon Barzai- Lilit -Astartaros Magan- Gnosis of Lilith -James L George- Lilith Invocation -Lucien von Wolfe- Three Rituals for the Queen of Night -Chertograd Daemon- Lilith:The Spider Queen of the Qlipoth -Daemon Barzai- The womb of art -Tim Katteluhn- Lilith as the Great Qabalistic Initiator -Rev Bill Duvendack- My Triple Goddess Lilith My Eternal Freedom -Selene-Lilith- Lilith Serpina -James George- Rite of the Seduction of the Virgin -Matthew Wightman- Lilit and the consorts of Samael -Yla Ysgarlad- Lilith Poetry -Ari- The Pilgrimage of Viryklu -Luis G. Abbadie- The Baptism of Witchblood -Kazim- The Evocation of Lilith -Daemon Barzai- List of Illustrations and Artwork: Lilith - Kazim- Arachnid Lilith -Salomelihecatel- Isheth Zenunim -Edgar Kerval- Lilith - Sitra Ahra -Soror Basilisk- Possession - Soror Basilisk- Lilith - Anna Krajewski- Samshan Lilith -Kazim- Foreword Lilith is one of the most well known Goddesses within the Left Hand Path magic and this anthology was written from different points of view, with different visions, experiences and personal gnosis. -

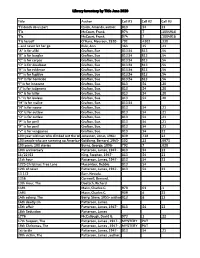

Library Inventory by Title June 2020 Title Author Call

Library Inventory by Title June 2020 Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Call #3 'Til death do us part Quick, Amanda, author. 813 .54 23 'Tis McCourt, Frank. 974 .7 .1004916 'Tis McCourt, Frank. 974 .7 .1004916 'Tis herself O'Hara, Maureen, 1920- 791 .4302 .330 --and never let her go Rule, Ann. 364 .15 .23 "A" is for alibi Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "B" is for burglar Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "C" is for corpse Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "D" is for deadbeat Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "E" is for evidence Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "F" is for fugitive Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "H" is for homicide Grafton, Sue 813.54 813 .54 "I" is for innocent Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "J" is for judgment Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "K" is for killer Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "L" is for lawless Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .20 "M" is for malice Grafton, Sue. 813.54 "N" is for noose Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "P" is for peril Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "P" is for peril Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 .21 "V" is for vengeance Grafton, Sue. 813 .54 22 100-year-old man who climbed out the windowJonasson, and disappeared, Jonas, 1961- The 839 .738 23 100 people who are screwing up America--andGoldberg, Al Franken Bernard, is #3 1945- 302 .23 .0973 100 years, 100 stories Burns, George, 1896- 792 .7 .028 10th anniversary Patterson, James, 1947- 813 .54 22 11/22/63 King, Stephen, 1947- 813 .54 23 11th hour Patterson, James, 1947- 813 .54 23 1225 Christmas Tree Lane Macomber, Debbie 813 .54 12th of never Patterson, James, 1947- 813 .54 23 13 1/2 Barr, Nevada. -

Heret, by Illustrator and Comics Creator Dan Mucha and Toulouse Letrec Were in Brereton

Featured New Items FAMOUS AMERICAN ILLUSTRATORS On our Cover Specially Priced SOI file copies from 1997! Our NAUGHTY AND NICE The Good Girl Art of Highest Recommendation. By Bruce Timm Publisher Edition Arpi Ermoyan. Fascinating insights New Edition. Special into the lives and works of 82 top exclusive Publisher’s artists elected to the Society of Hardcover edition, 1500. Illustrators Hall of Fame make Highly Recommended. this an inspiring reference and art An extensive survey of book. From illustrators such as N.C. Bruce Timm’s celebrated Wyeth to Charles Dana Gibson to “after hours” private works. Dean Cornwell, Al Parker, Austin These tastefully drawn Briggs, Jon Whitcomb, Parrish, nudes, completed purely for Pyle, Dunn, Peak, Whitmore, Ley- fun, are showcased in this endecker, Abbey, Flagg, Gruger, exquisite new release. This Raleigh, Booth, LaGatta, Frost, volume boasts over 250 Kent, Sundblom, Erté, Held, full-color or line and pencil Jessie Willcox Smith, Georgi, images, each one full page. McGinnis, Harry Anderson, Bar- It’s all about sexy, nubile clay, Coll, Schoonover, McCay... girls: partially clothed or fully nude, of almost every con- the list of greats goes on and on. ceivable description and temperament. Girls-next-door, Society of Illustrators, 1997. seductresses, vampires, girls with guns, teases...Timm FAMAMH. HC, 12x12, 224pg, FC blends his animation style with his passion for traditional $40.00 $29.95 good-girl art for an approach that is unmistakably all his JOHN HASSALL own. Flesk, 2021. Mature readers. NOTE: Unlike the The Life and Art of the Poster King first, Timm didn’t sign this second printing. -

I SOUTHERN MONSTERS in SOUTHERN SPACES

i SOUTHERN MONSTERS IN SOUTHERN SPACES: TRANSNATIONAL ENGAGEMENTS IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION by CHRISTEN ELIZABETH HAMMOCK (Under the Direction of JOHN LOWE) ABSTRACT Vampires, zombies, and other monsters have long been written about as a narrative space to work through collective anxieties, and the latest incarnation of these paranormal stories is no exception. What is remarkable is that many of these stories have adopted a Southern setting to explore Otherness. In this thesis, I seek to explore the role that Southern milieus plays in three television shows: The Walking Dead, True Blood, and Dexter. These shows are deeply invested in the culture and history of different “Souths,” ranging from the “Old South” of rural Georgia to a new, transnational South in Miami, Florida. I argue that this trend stems from the South’s hybrid existence as both colonizer and colonized, master and slave, and that a nuanced engagement with various Souths presents a narrative space of potential healing and rehabilitation. INDEX WORDS: Vampires; Zombies; Dexter; The Walking Dead; True Blood; Transnational; Southern literature; Television; U.S. South i SOUTHERN MONSTERS IN SOUTHERN SPACES: TRANSNATIONAL ENGAGEMENTS IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION by CHRISTEN ELIZABETH HAMMOCK A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2014 ii © 2014 Christen Elizabeth Hammock All Rights Reserved iii SOUTHERN MONSTERS IN SOUTHERN SPACES: TRANSNATIONAL ENGAGEMENTS -

Marvel-Phile

by Steven E. Schend and Dale A. Donovan Lesser Lights II: Long-lost heroes This past summer has seen the reemer- 3-D MAN gence of some Marvel characters who Gestalt being havent been seen in action since the early 1980s. Of course, Im speaking of Adam POWERS: Warlock and Thanos, the major players in Alter ego: Hal Chandler owns a pair of the cosmic epic Infinity Gauntlet mini- special glasses that have identical red and series. Its great to see these old characters green images of a human figure on each back in their four-color glory, and Im sure lens. When Hal dons the glasses and focus- there are some great plans with these es on merging the two figures, he triggers characters forthcoming. a dimensional transfer that places him in a Nostalgia, the lowly terror of nigh- trancelike state. His mind and the two forgotten days, is alive still in The images from his glasses of his elder broth- MARVEL®-Phile in this, the second half of er, Chuck, merge into a gestalt being our quest to bring you characters from known as 3-D Man. the dusty pages of Marvel Comics past. As 3-D Man can remain active for only the aforementioned miniseries is showing three hours at a time, after which he must readers new and old, just because a char- split into his composite images and return acter hasnt been seen in a while certainly Hals mind to his body. While active, 3-D doesnt mean he lacks potential. This is the Mans brain is a composite of the minds of case with our two intrepid heroes for this both Hal and Chuck Chandler, with Chuck month, 3-D Man and the Blue Shield. -

Violent Crimes

Violent Crimes In This Issue Making a Federal Case out of a Death Investigation . 1 By C.J. Williams January 2012 Murder-for-Hire . .9 Volume 60 By Jeff Breinholt Number 1 United States The Hobbs Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1951 . 18 Department of Justice Executive Office for By Andrew Creighton United States Attorneys Washington, DC 20530 Prosecuting Robberies, Burglaries, and Larcenies Under the Federal H. Marshall Jarrett Director Bank Robbery Act . 28 By Jerome M. Maiatico Contributors' opinions and statements should not be considered an endorsement by EOUSA for any policy, program, Repurposing the Kidnapping and Hostage Taking Statutes to Combat or service. Human Trafficking . 36 The United States Attorneys' Bulletin is published pursuant to 28 By Erin Creegan CFR § 0.22(b). The United States Attorneys' Carjacking . 46 Bulletin is published bimonthly by the Executive Office for By Julie Wuslich United States Attorneys, Office of Legal Education, 1620 Pendleton Street, Columbia, South Carolina 29201. Threats . 52 By Jeff Breinholt Managing Editor Jim Donovan Countering Attempts, Interference, and New Forms of Air Violence . 67 Law Clerk Carmel Matin By Erin Creegan Internet Address www.usdoj.gov/usao/ reading_room/foiamanuals. html Send article submissions and address changes to Managing Editor, United States Attorneys' Bulletin, National Advocacy Center, Office of Legal Education, 1620 Pendleton Street, Columbia, SC 29201. Making a Federal Case out of a Death Investigation C.J. Williams Assistant United States Attorney Senior Litigation Counsel Northern District of Iowa I. Introduction How do you respond, as an Assistant United States Attorney, when an agent walks into your office and says, "I've got an investigation involving a death. -

John Grisham a Time to Kill

John Grisham A Time to Kill Billy Ray Cobb was the younger and smaller of the two rednecks. At twenty-three he was already a three-year veteran of the state penitentiary at Parchm^an. Possession, with intent to sell. He was a lean, tough little punk who had survived prison by somehow maintaining a ready supply of drugs th^at he sold and sometimes gave to the blacks and the guards for protection. In the year since his release he had continued to prosper, and his small-time narcotics business had elevated him to the position of one of the more affluent rednecks in Ford County. He was a businessman, with employees, obligations, deals, everything but taxes. Down at the Ford place in Clanton he was known as the last man in recent history to pay cash for a new pickup truck. Sixteen thousand cash, for a custom-built, four-wheel drive, canary yellow, luxury Ford pickup. The fancy chrome wheels and mudgrip racing tires had been received in a business deal. The rebel flag hanging across the rear window had been stolen by Cobb from a drunken fraternity boy at an Ole Miss football game. The pickup was Billy Ray's most prized possession. He sat on the tailgate drinking a beer, smoking a joint, watching his friend Willard take his turn with the black girl. Willard was four years older and a dozen years slower. He was generally a harmless sort who had never been in serious trouble and had never been seriously employed. Maybe an occasional fight with a night in jail, but nothing that would distinguish him.