IRAKI NEW.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

(Sasl) in a Bilingual-Bicultural Approach in Education of the Deaf

APPLICATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN SIGN LANGUAGE (SASL) IN A BILINGUAL-BICULTURAL APPROACH IN EDUCATION OF THE DEAF Philemon Abiud Okinyi Akach August 2010 APPLICATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN SIGN LANGUAGE (SASL) IN A BILINGUAL-BICULTURAL APPROACH IN EDUCATION OF THE DEAF By Philemon Abiud Omondi Akach Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR in the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES (DEPARTMENT OF AFROASIATIC STUDIES, SIGN LANGUAGE AND LANGUAGE PRACTICE) at the UNIVERSITY OF FREE STATE Promoter: Dr. Annalie Lotriet. Co-promoter: Dr. Debra Aarons. August 2010 Declaration I declare that this thesis, which is submitted to the University of Free State for the degree Philosophiae Doctor, is my own independent work and has not previously been submitted by me to another university or faculty. I hereby cede the copyright of the thesis to the University of Free State Philemon A.O. Akach. Date. To the deaf children of the continent of Africa; may you grow up using the mother tongue you don’t acquire from your mother? Acknowledgements I would like to say thank you to the University of the Free State for opening its doors to a doubly marginalized language; South African Sign Language to develop and grow not only an academic subject but as the fastest growing language learning area. Many thanks to my supervisors Dr. A. Lotriet and Dr. D. Aarons for guiding me throughout this study. My colleagues in the department of Afroasiatic Studies, Sign Language and Language Practice for their support. Thanks to my wife Wilkister Aluoch and children Sophie, Susan, Sylvia and Samuel for affording me space to be able to spend time on this study. -

Iconicity As a Pervasive Force in Language: Evidence from Ghanaian Sign

Iconicity as a pervasive force in language: Evidence from Ghanaian Sign Language and Adamorobe Sign Language By Mary Edward A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities University of Brighton 2021 Abstract In this dissertation, I investigate various manifestations of iconicity and how these are demonstrated in the visual-spatial modality, focusing specifically on Ghanaian Sign Language (GSL) and Adamorobe Sign Language (AdaSL). The dissertation conducts three main empirical analyses comparing GSL and AdaSL. The data for the analyses were elicited from deaf participants using lexical elicitation and narrative tasks. The first study considers iconicity in GSL and AdaSL lexical items. This study additionally compares the iconic strategies used by signers to those produced in gestures by hearing non-signers in the surrounding communities. The second study investigates iconicity in the spatial domain, focusing on the iconic use of space to depict location, motion, action. The third study looks specifically at the use of, simultaneous constructions, and compares the use of different types of simultaneous constructions between the two sign languages. Finally, the dissertation offers a theoretical analysis of the data across the studies from a cognitive linguistics perspective on iconicity in language. The study on lexical iconicity compares GSL and AdaSL signers’ use of iconic strategies across five semantic categories: Handheld tools, Clothing & Accessories, Furniture & Household items, Appliances, and Nature. Findings are discussed with respect to patterns of iconicity across semantic categories, and with respect to similarities and differences between signs and gestures. -

A Lexical Comparison of South African Sign Language and Potential Lexifier Languages

A lexical comparison of South African Sign Language and potential lexifier languages by Andries van Niekerk Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Masters in General Linguistics at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisors: Dr Kate Huddlestone & Prof Anne Baker Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Department of General Linguistics March, 2020 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Andries van Niekerk March 2020 Copyright © 2020 University of Stellenbosch All rights reserved 1 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT South Africa’s history of segregation was a large contributing factor for lexical variation in South African Sign Language (SASL) to come about. Foreign sign languages certainly had a presence in the history of deaf education; however, the degree of influence foreign sign languages has on SASL today is what this study has aimed to determine. There have been very limited studies on the presence of loan signs in SASL and none have included extensive variation. This study investigates signs from 20 different schools for the deaf and compares them with signs from six other sign languages and the Paget Gorman Sign System (PGSS). A list of lemmas was created that included the commonly used list of lemmas from Woodward (2003). -

Chapter 4 Deaf Children's Teaching and Learning

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details TEACHING DEAF LEARNERS IN KENYAN CLASSROOMS CECILIA WANGARI KIMANI SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY FEBRUARY 2012 ii I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another university for the award of any other degree. Signature: ……………………… iii Table of Contents Summary.........................................................................................................................ix Acknowledgements.........................................................................................................xi Dedication.......................................................................................................................xii List of tables..................................................................................................................xiii List of figures................................................................................................................xiv -

AFRICAN SIGN LANGUAGES WORKSHOP PROGRAM Includes Most of Europe, South Africa, Egypt, More Info: Malawi, Sudan, Rwanda, Zambia, Etc

WORLD CONGRESS OF AFRICAN LINGUISTICS 10 (WOCAL10), LEIDEN UNIVERSITY Schedule is in timezone of conference site (Central European Time; GMT+2 in DST). This AFRICAN SIGN LANGUAGES WORKSHOP PROGRAM includes most of Europe, South Africa, Egypt, more info: http://sign.wocal.net Malawi, Sudan, Rwanda, Zambia, etc. For more timezones, see Page 2 RECEPTION: 6:00-7:30PM SATURDAY, JUNE 5, 2021 DAY 1 MONDAY, JUNE 7, 2021 DAY 2 TUESDAY, JUNE 8, 2021 DAY 3 WEDNESDAY, JUNE 9, 2021 DAY 4 THURSDAY, JUNE 10, 2021 DAY 5 FRIDAY, JUNE 11, 2021 START TIME EVENT START TIME EVENT START TIME EVENT START TIME EVENT START TIME EVENT WORKSHOP OPENING; Introductions 4:00PM Daily opening 4:00PM Daily opening 3:00PM Plenary: Woinshet Girma (moderator, interpreters, authors), Zoom WOCAL Committee on African Sign 4:00PM TBD Theme: Documentation and language comparisons Theme: Language origins and 3:40PM Break before sessions start protocols & instructions, announcements Languages meeting (all participants invited) language of expression 4:00PM Daily opening Theme: African sign languages in use: Annie Risler, Alain Gebert • The 4:00PM Daily opening Ingeborg Groen • Anger expression in Theme: African sign languages and across borders and in the home Dictionary for Seychellois Sign Language: 4:10 PM Theme: Lexical variation and new methods 4:10PM Ghanaian Sign Language (GSL) deaf students in the classroom Amandine le Maire • Mobilities / A tool forthe preservation, transmission Anne Baker, Andries van Niekerk, Kate Hope E. Morgan, Evans N. Burichani, Yede Adama Sanogo • Sign language 4:10PM Immobilities of deaf people in Kakuma and development of Seychelles' heritage Huddlestone • Studying lexicalvariation Jared O. -

The Deaf of South Sudan the South Sudanese Sign Language Community South Sudan Achieved Its Independence in 2011 from the Republic of Sudan to Its North

Profile Year: 2015 People and Language Detail Report Language Name: South Sudan Sign Language ISO Language Code: not yet The Deaf of South Sudan The South Sudanese Sign Language Community South Sudan achieved its independence in 2011 from the Republic of Sudan to its north. Prior to that, Sudan suffered under two civil wars. The second, which began in 1976, pitted the Sudanese government against the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and lasted for over twenty years. These wars have led to significant suffering among the Sudanese and South Sudanese people, including major gaps in infrastructure development and significant displacement of various people groups. All of this war has traumatized the people of Sudan, and the Deaf in particular. The country appears to have a very small middle class, while a vast majority of its citizens are either very wealthy or extremely poor. The Deaf in South Sudan tend to be the poorest of the poor. Some cannot afford food and must stay at home with families (even though the home environ- ment often means that no one can communicate with them). There are currently no Deaf schools in South Sudan. Deaf schools are photo by DOOR International typically the center of language and cultural development for the Deaf of a country. A lack of Deaf schools means that there is a need for a central cultural organization among the Deaf. Deaf churches could function in this Primary Religion: role if they were well-established. There is currently only one Deaf church in Non-religious __________________________________________________ South Sudan. This church meets in Juba, and has fewer than 50 members. -

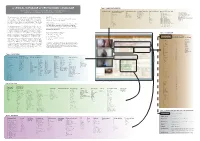

A LEXICAL DATABASE of KENYAN SIGN LANGUAGE Table 1

A LEXICAL DATABASE of KENYAN SIGN LANGUAGE Table 1. HAND CONFIGURATION Hope E. Morgan • University of California San Diego • [email protected] number of hands main articulator (primary), handshape symmetry movement symmetry SignType (Battison) geometry of the two hands ‘Digging into Signs’ Workshop; UCLondon, March 30 - April 1, 2015 1 secondary articulator same simultaneous X mirror end-stacked; tips same 2 hand different simult; connected 0 mirror; alternating end-stacked; tips opposite 1 or 2 hand (stiff wrist) same, same simult; h2 stationary 0/X mirror; alternating; asymmetric end-stacked; tips perpendicular forearm different, same alternating 1 mirror; offset adjacent; ranked prox-dist This poster presents an ongoing project to code the lexical prop- METHODS: arm same, different H2 stationary 2 mirror; asymmetric perpendicular plane head complex 3 stacked; tips same same plane; adjacent; tips perpindicular erties of signs in Kenyan Sign Language (KSL)* including pho- Participants: 28 deaf signers in total, though the majority face 3-minimal stacked; tips opposite h2 base eyes 3-move stacked; tips perpendicular h1 under h2 netic, phonemic, iconic, semantic, grammatical, and etymologi- of signs were produced by 3 signers mouth 4 stacked; facing; tips same n/a cal, with the focus here on phonetic properties. The ultimate author tongue C stacked; facing; tips opposite Coder: teeth unsure stacked; facing; tips perpendicular future goal is to link these lexical records to a full corpus of KSL. Language genres: (1) elicitation of citation forms by author whole body stacked; opposite facing; tips perpendicular with deaf Kenyan participant, (2) dyadic exchanges be- upper body side-stacked; tips same The database was created in FileMaker Pro, allowing for maxi- clothes side-stacked; tips opposite tween deaf Kenyans doing communiative tasks, (3) group not sure side-stacked; tips perpendicular mum flexibility during coding (see data entry screen in Fig. -

Stakeholders' Views on Use of Sign Language Alone As a Medium Of

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SPECIAL EDUCATION Vol.33, No.1, 2018 Stakeholders’ Views on Use of Sign Language Alone as a Medium of Instruction for the Hearing Impaired in Zambian Primary Schools Mandyata Joseph, Kamukwamba Kapansa Lizzie, School of Education, University of Zambia ([email protected]) Abstract The study examined views of stakeholders on the use of Sign Language as a medium of instruction in the learning of hearing impaired in primary schools of Lusaka, Zambia. A case study design supported by qualitative methods was used. The sample size was 57, consisting of teachers, pupils, curriculum specialist, education standards officers, lecturers and advocators on the rights of persons with disabilities. Purposive sampling techniques to selected the sample, interview and focused group discussion guides were tools for data collection. The study revealed significant differences in views of stakeholders on use of Sign Language alone as medium of instruction. While most participants felt sign language alone was ideal for learning, others believed learners needed exposure to total communication (combination of oral and sign language) to learn better. Those who felt using sign language alone was better, believed the practice had more positive effects on learning and that use of oral language, total communication often led to confusion in classroom communication among learners with hearing impairments. Participants who opposed use of sign language alone were of the view teachers: were ill-prepared; signs were limited in scope; education system lacked instructional language policy and learning environment were inappropriate to support use of sign language alone in the learning process. The study recommended strengthening of training of sign language teachers and introduction of sign language as an academic subject before it can be used as the sole medium of classroom instruction in the Zambian primary schools. -

Competition Materials

Competition Opens: 8 November 2017 Closing Date: 16 February 2018 Sign On For Literacy Prize Page 2 of 20 Sign On For Literacy All Children Reading: A Grand Challenge for Development Application Document Contents Summary 3 Background 3 About All Children Reading: A Grand Challenge for Development 5 The Challenge 5 Solution Requirements 7 Resources 9 Competition and Phases 10 Submission Questions 12 Judging Criteria for Phase 1 14 Terms and Conditions 16 Sign On For Literacy Prize Page 3 of 20 Summary Acquisition of a first language is essential for early childhood development and a building block for learning to read. Literacy is linKed to all development goals contributing to psycho-social health, employment opportunities, economic growth, and breaKing the cycle of poverty. Globally for children who are deaf, hard of hearing and deafblind (henceforth referred to as ‘Deaf’∗), access to and education in a local sign language is often limited or absent. Without access to whole language with frequent and daily input to an accessible and natural language, the foundations of literacy, children are prevented from reaching their full potential. In developing countries and low-resource contexts, literacy outcomes for children who are Deaf are particularly substandard. As such, All Children Reading: A Grand Challenge for Development is launching the Sign On For Literacy Prize, which seeks technology-based innovations to increase access to local sign languages and develop literacy interventions for children who are Deaf in low-resource contexts. Winning innovations must be novel, while utilizing technology to maKe a significant impact upon learning and literacy in the Deaf Community. -

![“Ugandan Sign Language [Ugn] (A Language of Uganda)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1587/ugandan-sign-language-ugn-a-language-of-uganda-1921587.webp)

“Ugandan Sign Language [Ugn] (A Language of Uganda)

“Ugandan Sign Language [ugn] (A language of Uganda) • Alternate Names: USL • Population: 160,000 (2008 WFD). 160,316–840,000 deaf (2008 WFD, citing various sources). 528,000–800,000 deaf (Lule and Wallin 2010, citing various sources). Over 700,000 deaf adults (Oluoch 2010, citing 2002 Uganda Bureau of Statistics). Figures range from 0.5%–2.7% of the general population of approx. 31,000,000. • Location: Scattered, mainly in urban areas. • Language Status: 5 (Developing). Recognized language (1995, Constitution, Article XXIV(d)). • Classification: Deaf sign language • Dialects: None known. Historical influence from British Sign Language [bfi], American Sign Language [ase] and Kenyan Sign Language [xki], but clearly distinct from all three. Influence from English [eng] in grammar, mouthing, initialization, fingerspelling (both one-handed and two-handed systems), especially among young, urban Deaf. Some mouthing from Luganda [lug] and Swahili [swa] (Lule and Wallin 2010). • Typology: One-handed and two-handed fingerspelling. • Language Use: Schools for deaf children since 1959. 8 primary schools and 2 secondary for the deaf; mixture of bilingual education and Total Communication (WFD Regional Secretariat for Southern and Eastern Africa 2008). Sign language in classrooms tends to be Signed English, especially by hearing teachers; some teachers are Deaf. Some schools are residential; education at preschool through vocational and university levels, but not available to all deaf children; many are in mainstream settings (Lule and Wallin 2010). Interpreters available for university, social, medical and religious services, courts, parliament, etc. (WFD Regional Secretariat for Southern and Eastern Africa 2008). Positive attitudes towards USL among Deaf; negative attitudes still common among hearing (Lule and Wallin 2010). -

Official Language Designation

Official Language Designation Constitution-Building Primer 20 Official Language Designation International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 20 Sujit Choudhry and Erin C. Houlihan © 2021 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/>. Cover illustration: © 123RF, <http://123rf.com> Design and layout: International IDEA DOI: <https://doi.org/10.31752/idea.2021.40> ISBN: 978-91-7671-412-6 (PDF) Created with Booktype: <https://www.booktype.pro> Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 6 Defining ‘official’ and ‘national’ languages .............................................................. 6 Advantages and risks ............................................................................................... 7 Where