The “No Dirty Gold” Campaign: What Economists Can Learn from And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nexus of Illegal Gold Mining Supply Chains Lessons from Latin America GOLD PRODUCTION Gold Is an Extremely Scarce Commodity

The Nexus of Illegal Gold Mining Supply Chains Lessons from Latin America GOLD PRODUCTION Gold is an extremely scarce commodity. The amount of gold swimming pools,1 and almost three-quarters of all of the world’s gold deposits have already been exhausted.2 Due to increasing the world now consumes more gold than ever before, leading to the production of 3,000 tons of gold per year, twice what was produced in 1970. The diminishing supply and increasing demand, combined with criminal and armed groups’ quest for new sources of illicit revenue, has contributed to a surge in illegal extraction of gold from increasingly remote and lawless regions.3 Introduction In-depth research carried out by Verité has found that Latin American countries export reputational risks for major companies with gold in their supply chains. The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, with which Verité has been closely collaborating, recently released an in-depth report thoroughly documenting the close link between illegal gold mining and organized crime, which fuels violence, environmental damage, corruption, money Verité publications include a research report focusing on illegal gold mining in Colombia and Latin American countries, a white paper with detailed recommendations for companies and along with Canada other stakeholders to ensure that illegally mined gold does not (which is a major conduit enter into company supply chains and the vaults of central banks. for Latin American gold), constitute all top ten exporters of gold to the research carried out by Verité in Peru in 2012-2013 and in Colombia United States. in 2015, and desk research carried out across the Latin American region. -

Injustice Challenging

Oxfam ExchSPRINGa 2006 nge CHALLENGING INJUSTICE R HEALTH CRISIS SPURS CAMPAIGN R COFFEE FARMERS DEMAND FOR ENVIRONMENT IN PERU ROLE IN INTERNATIONAL COFFEE ORGANIZATION R CONTROVERSY SURROUNDING GOLD MINING GROWS AS JEWELERS SPEAK OUT R CITIZENS WORK FOR PEACE IN AFRICA s 3 RIGHT NOW: AMPLIFYING A GLOBAL VOICE t 4 POLICY UPDATE: FAILING TO BE FAIR AT THE n WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION e OXFAM EXCHANGE t 5-14 CHALLENGING INJUSTICE Volume 6, Number 2 R n Controversy Surrounding Gold Mining Grows as Spring 2006 Jewelers, Indigenous Community Leaders Speak Out DIANE SHOHET o Managing Editor R From One Voice to a Chorus: Residents Organize CHRIS HUFSTADER c COCO McCABE in the Gulf Coast ANDREA PERERA Writers R Health Crisis Spurs Campaign for Environment in Peru STEPHEN GREENE R Copy Editor Coldplay Campaigns to Make Trade Fair JEFF DEUTSCH R Coffee Farmers Demand Role in International Graphic Designer MAIN OFFICE Coffee Organization 26 West Street Boston, MA 02111-1206 USA R Citizens Work for Peace and Justice in Africa 800/77-OXFAM [email protected] WASHINGTON OFFICE 1112 16th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 USA [email protected] Announcing a New Organization: OXFAM AMERICA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Janet A. McKinley Chair We are pleased to announce the Oxfam America Advocacy Fund. Raymond C. Offenheiser President The Oxfam America Advocacy Fund is a new nonprofit organization that Kapil Jain was founded by Oxfam America to support advocacy efforts that are L. David Brown David Doniger essential to our efforts to overcome poverty, hunger and injustice. Peter C. Munson Kitt Sawitsky The Oxfam America Advocacy Fund is a 501c(4) organization that does Roger Widmann Akwasi Aidoo not have any dollar restrictions on lobbying, so it will enable Oxfam to carry The Honorable Chester Atkins David Bryer out all of the advocacy and lobbying actions that we feel are necessary to John Calmore Michael Carter achieve our mission. -

5 0T H International Film Festival Nyon

50 INDUSTRY — VISIONSRÉEL DU 5 0 TH INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL NYON 5 13 APRIL 2019 MAIN PARTNER MEDIA PARTNER INSTITUTIONAL PARTNERS EDITION NO 50 SUMMARY EDITORIAL 5 DAY BY DAY 6 JURY & AWARDS 8 PITCHING DU RÉEL 15 DOCS IN PROGRESS 59 ROUGH CUT LAB 79 SUMMARY PRIX RTS: PERSPECTIVES D’UN DOC 93 SWITZERLAND MEETS... QUÉBEC 103 OPENING SCENES LAB 115 DOC & ART 127 INDUSTRY TALKS 129 IMMERSIVE & INTERACTIVE 132 MEDIA LIBRARY 133 NETWORKING 134 SPECIAL EVENTS 136 MAP & INFORMATION 137 INDUSTRY TEAM 138 SPECIAL THANKS & PARTNERS 139 PROJECTS’ INDEX 142 3 EDITORIAL EMILIE BUJÈS GUDULA MEINZOLT ARTISTIC DIRECTOR HEAD OF INDUSTRY This year, the Festival is celebrating its selected by the Festival’s programmers; 50th edition. Fifty years during which Switzerland meets… Québec, which will Visions du Réel has taken many forms be the occasion for coproduction meet- and directions, has played an essen- ings between producers and institutions EDITORIAL tial role in the festival landscape, both aiming to network; the Opening Scenes in Switzerland and abroad. Revisiting Lab, a programme made for 16 filmmak- and celebrating history on the Festival ers taking part in the Opening Scenes side and with an ofcial selection to be Competition, that allows them to get proud of (no less than 90 films presented better acquainted with the market and as world premieres), the Industry aims to decision makers. bear witness of richness and strength of cinema of the real, not only for today but Several conferences, panels, debates, also in the years to come. work sessions and case studies will take place and are possible thanks to collab- We have selected 27 strong, provoca- orations and partnerships with organisa- tive and diverse projects for our three tions and institutions we are very happy diferent sections: Pitching du Réel, Docs and proud to be working with: On & For in Progress and Rough Cut Lab. -

CFDA Guide to Sustainable Strategies

CFDA Guide to Sustainable Strategies Guide to Sustainable Strategies CFDA.com P. 1 CFDA Guide to Sustainable Strategies Steven Kolb President & CEO Sara Kozlowski Director of Education & Professional Development Council of Fashion Designers of America Publisher Domenica Leibowitz Author Lauren Croke Contributor Aldo Araujo Cal McNeil Jackie Shihadeh Johanna Sapicas Joseph Maglieri Kelsey Fairhurst Marc Karimzadeh Mark Beckham Sofia Cerda Campero Stephanie Soto Editors CFDA.com P. 2 CFDA Guide to Sustainable Strategies SUSTAINABILITY GUIDE Introduction This CFDA Guide to Sustainable Strategies provides a “how to” overview for sustainable fashion with a focus on helping our members and community create, meet, and exceed their own unique sustainability goals. Our goal is to take the complex idea of sustainability and simplify it into clear, digestible resources and actions. In order for the industry to change we need to work together. This guide is available to public as a critical educational resource. Through this project we seek to shift sustainable practices among members as well as across the entire industry. CFDA.com P. 3 CFDA Guide to Sustainable Strategies SUSTAINABILITY GUIDE How to use this guide Your sustainability journey is uniquely your own. While this guide has been created to help you succeed, how you choose to use it is entirely up to you. We like to think of each sustainability section as one component of good design; there is no linear order to how you need to implement it. Start with the big questions about your company: Who are we? Why do we create? What do we care about? What does sustainability mean to us? The answers to these questions will determine where you will begin. -

The First Draft: Deja Vu

Internet News Record 27/07/09 - 28/07/09 LibertyNewsprint.com U.S. Edition The First Draft: Deja vu - it’s China EU to renew US bank and healthcare again scrutiny deal By Deborah Charles (Front Row (BBC News | Americas | World terrorism investigators first came to Washington) Edition) light in 2006. The data-sharing agreement was struck in 2007 after Submitted at 7/28/2009 6:04:13 AM Submitted at 7/28/2009 3:04:02 AM European data protection authorities Presidents are never afraid of The EU plans to renew an demanded guarantees that European beating the same drum twice. agreement allowing US officials to privacy laws would not be violated. Today, President Barack Obama scrutinise European citizens' banking Speaking on Monday, EU Justice continues his quest to boost support activities under US anti-terrorism Commissioner Jacques Barrot said "it for healthcare reform with a “tele- laws. would be extremely dangerous at this town hall” at AARP. Then he talks EU member states have agreed to stage to stop the surveillance and the about relations with China, just like let the European Commission monitoring of information flows". on Monday. negotiate new conditions under A senior member of Germany's With Obama’s drive for healthcare which the US will get access to ruling Christian Democrats (CDU), reform stalled in the Senate and the private banking data. Wolfgang Bosbach, said any new House — even though both chambers US officials currently monitor agreement had to provide "certainty are controlled by his fellow transactions handled by Swift, a huge about data protection and ensure that Democrats — the president is inter-bank network based in the personal data of respectable looking to ordinary Americans to Belgium. -

Apple's Dirty Gold Problem

Apple’s Dirty Gold Problem Apple has touted its efforts to clean up the trade in conflict minerals like gold. But the company has long relied on gold suppliers linked to money laundering and other illegal activity. Apple has repeatedly used gold suppliers implicated in money laundering, human rights abuses, and sanctions evasion, according to a Tech Transparency Project (TTP) investigation, raising questions about the company’s reputation as an industry leader in responsible supply chain management. The tech giant has won praise from some activists for doing more than its corporate peers to halt the trade in so-called conflict minerals such as gold, which has funded violent conflicts and criminal groups in Africa and Latin America. But TTP found that despite its reputation, Apple has for years relied on a range of suppliers linked to the global trade in “dirty gold.” Across Africa, the gold trade is often run by paramilitary groups that profit from child labor and use the proceeds to fund civil wars. In Latin America, drug cartels use gold refineries to launder illicit proceeds. This dirty gold is sold to prominent refineries and brokers who re-process and re- brand it, allowing it to slip into the global supply chain. Many of Apple’s suppliers have obtained gold from the Kaloti Group, a Dubai-based refinery that has repeatedly been linked to the trade in dirty gold. The Kaloti Group garnered international attention when an auditor at Ernst & Young discovered that the refinery was allegedly smuggling gold and laundering money. The global accounting firm refused to take action and allegedly forced the auditor, Amjad Rihan, out of his job.1 Rihan alleged his audit team had also uncovered Kaloti transactions involving gold imported from Sudan and Iran, both subject to U.S. -

Record Store Day 2015 Product List

RECORD STORE DAY 2015 PRODUCT LIST www.recordstoreday.co.uk @RSDUK FB /RSDAYUK INSTAGRAM: recordstoreday Artist Title Format !!! All U Writers / Gonna Guetta Stomp 12" 16 horsepower Olden Lpx2 16 horsepower Folklore Lp 999 BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT/ BIGGEST TOUR IN DLP SPORT A pregnant light St. Emaciation 7 A$ap rocky "lpfj2 / multiply" 7" vinyl Ad libs, the You'll always be in style/the boy from new 7" york city Adam & the ants "kings of the wild frontier / ant music" 7" vinyl Adonis No Way Back (Azari & III / Mixhell Covers) 12" A-ha Take On Me 10" / picture disc Air Playground Love 7" / coloured vinyl Alex chilton Jesus christ 7" Alex harvey Midnight moses / jumping jack flash 7" single Amir Alexander presents Richie The Infinity! EP 12" Ratchet Amon tobin Dark jovian 2x12" box set Angelic upstarts Last tango in moscow Dlp Animal collective Prospect hummer Lp Annabel (lee) If Music presents: By the sea... And other LP solitary places Anne briggs Anne briggs Lp Anthony phillips The geese and the ghost Lp Antorchas S/t 7" Art (a.k.a. Spooky Tooth) What's That Sound (For What It's Worth) / 7" Single Rome Take Away Three Automat/camera Automat/camera 12" Badbadnotgood feat. Ghostface Stone sour (instrumentals) Lp killah B Movie They Forgeot / Trash & Mystery 7” Bardo pond Is there a heaven 12" ep Barnett, courtney Kim's caravan 12" Barry brown The thompson sound 1979-82 7 x 7" Becky bell / the underground band Under the influence sampler 2015 ft dj red 12" / sweet talks & shelbra deane greg & joey negro edits Bee gees "extended" ep 12" ep -

Angel Dmx Download

Angel dmx download click here to download Lyrics to 'Angel' by DMX & Regina Bell. What good is it for a man to, gain the world / Yet lose his own soul, in the process? / God loves you, yes, He does. wow ooooooh. ~ Friday, September 28th , AM. DMX come back to music the industry missed uuuuuuuuuuuu so do ur fans. waliseth. Read about Angel (Featuring Regina Bell) (Album Version (Explicit)) by DMX and see the artwork, lyrics and similar artists. DMX - Angel - tekst piosenki, tłumaczenie piosenki i teledysk. Znajdź teksty piosenki oraz tłumaczenia piosenek i zobacz teledyski swoich ulubionych utworów. DMX – Angel (ft. Regina Belle). Artist: DMX, Song: Angel (ft. Regina Belle), Duration: , Size: MB, Bitrate: kbit/sec, Type: mp3. № PLAY DMX - Angel ft. Regina www.doorway.ru3 PLAY DMX - D-X-L (Hard White) ( featuring The Lox and Drag - On).mp3 · Download, M, , Freeallmusic - Angel song by artist DMX from Album ' And Then There Was X' is available for free download in kbps quality. Lyrics, Videos, ringtones also. 17 – Angel (Feat Regina Bell)and DMX. Artist: 17, Song: Angel (Feat Regina Bell) and DMX, Duration: , Type: mp3. № DMX - Angel Feat. Regina Belle (www.doorway.ru).mp3 >>> DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1). 1 / 3 . www.doorway.ru3;www.doorway.ruThat'www.doorway.ru .I'www.doorway.ru Regina Bell] [Explicit] by DMX on Amazon Music. Stream ad- free or Angel ( Featuring Regina Bell) [feat. Regina Bell] [Explicit]. DMX. From the Album And Then There Was X . DMX Stream or buy for $ Next . Download Audiobooks. Check out Angel (Featuring Regina Bell) [Explicit] [feat. Regina Bell] by DMX on Amazon Music. -

Angel Haze Släpper Debutalbumet Dirty Gold Den 13 Januari

2014-01-07 18:27 CET Angel Haze släpper debutalbumet Dirty Gold den 13 januari ”Smart, slående och originell.. Angel Haze” – The Guardian Angel Haze läckte själv debutalbumet Dirty Gold på Twitter med orden ”So sorry to Island/Republic Records, but fuck you” och därmed flyttades det amerikanska releasedatumet fram till den 30 december. De svenska fansen får hålla ut till den 13 januari. På albumet, som fått 4/5 i betyg av The Guardian, visar Angel upp sig som rappare, sångerska och låtskrivare. Dirty Gold har producerats i samarbete med Markus Dravs (Björk, Arcade Fire, Coldplay), Mike Dean (Kanye West), Greg Kurstin (Lily Allen) och Malay (Frank Ocean). Sia, som är albumets enda gästartist, medverkar på spåret ”Battle Cry” där hon tillsammans med Angel även skrivit texten. Angel växte upp i en frireligiös sekt och hennes barndom kantades av svåra övergrepp och misshandel. Tillsammans med sin mamma flydde hon till New York och fann musiken. För Rolling Stone Magazine beskriver hon albumtiteln Dirty Gold med orden: ”Gold comes from the dirt. It's underground and you mine it and make it better. That's how I view people. You go through your dirt and your tough stuff and you deal and you get better.“ Tracklist: 1. Sing About Me 2. Echelon (It’s My Way) 3. A Tribe Called Red 4. Deep Sea Diver 5. Synagogue 6. Angel + Airwaves 7. April’s Fools 8. White Lillies / White Lies 9. Battle Cry 10. Black Dahlia 11. Planes Fly 12. Dirty Gold Se musikvideon till albumets ledspår "Echelon (It's My Way)": Universal Music är Sveriges och världens ledande musikbolag med representation i hela 71 länder. -

The Issue Angel Haze

X AMBASSADORS • BETTY WHO • THE CHAINSMOKERS • JON BELLION • BOMBAY BICYCLE CLUB • SWITCHFOOT VARIANCETHE SIGHTS + SOUNDS YOU LOVE 40 ALBUMS TO WATCH FOR IN 2014 BASTILLE t ANGEL HAZE PHANTOGRAM JAMES VINCENT MCMORROW THE FUTURESOUNDS ISSUE VOICES THAT WILL REIGN THIS YEAR VOL. 5, ISSUE 1 | FEB_WINTER 2014 AVAILBLE NOW AT SKULLCANDY.COM @SKULLCANDY / FEATURING KAI OTTON Variancemagazine_Navigator_Kai.indd 1 12/14/12 3:10 PM TAPE MIX JAMES VINCENT MCMORROW PHANTOGRAM LILY ALLEN “Gold” “Black Out Days” “Hard Out Here” by @AlainUlises by @OJandCigs by @AleksaConic WINTER2014 VANCOUVER SLEEP CLINIC CHILDISH GAMBINO BOMBAY BICYCLE CLUB “Collapse” “telegraph ave. (‘Oakland’ by Lloyd)” “Carry Me” by @Jedshepherd by @tylersduke by @mardycum ANGEL HAZE FEAT. SIA JAMIE N COMMONS & X AMBASSADORS LO-FANG “Battle Cry” “Jungle” “#88” by @jenryannyc zz by @JK1KJ by @6n6challenge SAM SMITH MATTHEW MAYFIELD “Money on My Mind” “Heartbeat” by @AllenOVCH by @MissBehavinC YOU CREATE THE PLAYLIST ST. VINCENT "Digital Witness" Annie Clark foreshadows her new album with this catchy tune FIRSTTHINGSFIRST PHOTO BY KIM ERLANDSEN You” shot up the blogosphere last summer when video of a marriage proposal utilizing the song went viral. She’s since signed to RCA Records and is working on her major label debut. Also on the roster are X Ambassadors, the little band that could from Ithaca, N.Y. After teaming up with Alex Da Kid, who can do no wrong, in our opinion, the ris- ing act is expected to release a full-length this year. And based on everything we’ve heard so far, these guys will only continue to climb. -

P&C Music Rsd15 Titles Updated 8 April 2019

P&C MUSIC RSD15 TITLES UPDATED 8 APRIL 2019 ARTIST / TITLE PRODUCT INFO PRICE £ 1. 101ers, The: Elgin Avenue Breakdown (Revisited) LP, red vinyl. 7500 copies worldwide, available from 31.99 independent retailers only. 2. ART (Spooky Tooth): What's That Sound (For what It's worth) / Rome 7” single, 1000 copies. 13.99 3. BARRETT, Syd / R.E.M. [both perform] Dark globe 7” coloured vinyl split single in the ‘Side by Side’ 15.99 series.1500 copies. 4. BOWIE, David / VERLAINE, Tom [both perform] Kingdom come 7” split single, transparent red inside opaque black (colour 15.99 in colour). In the ‘Side by Side’ series. Available from independent retailers only. 5. BUSY P: Gypsy life 12” mini album. 80 copies for UK. 13.99 6. CASH, Johnny: The Man comes around / Personal Jesus 7” single, 1000 copies. 13.99 7. COBRA SKULLS: Live at the BBC 7” single 9.99 8. COLLINS, Shirley: English songs (first released 1960) 7” EP 7.99 9. CZUKAY, Holger: Hit / Flop (features Jah Wobble on bass) 2 x 10” in triple gatefold sleeve. Ltd edn. 17.99 10. DEAD MILKMEN: Beelzebubba LP on blue or random white vinyl. First time on vinyl in 35.99 US RSD RELEASE over 25 years! 11. DEEP PURPLE: Black night / Speed king 7" blue opaque vinyl in picture bag. 1050 13.99 copies 12. DEEP PURPLE: Live with orchestra at the Montreux Jazz Festival 16/7/11 3LP box set, 140g transparent purple vinyl. 1000 59.99 copies. 13. EL KHATIB, Hanni: Devil's Pie 7" picture disc of a pie (looks delicious). -

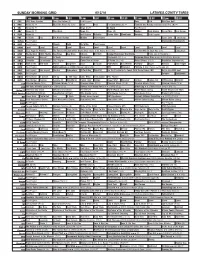

Sunday Morning Grid 6/12/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/12/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid F1 Countdown (N) Å Formula One Racing Canadian Grand Prix. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Explore Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Underworld: Evolution (R) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Easy Yoga for Arthritis The Forever Wisdom of Dr. Wayne Dyer Tribute to Dr. Wayne Dyer. (TVG) Eat Dirt With Dr. Josh Axe (TVG) Carpenters 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Louder Than Love: The Grande Pavlo Live in Kastoria Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Flashpoint Å Flashpoint (TV14) Å Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Baby Geniuses › (1999) Kathleen Turner.