Nubia and Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daniel Handout #1 Primary Documents Bible: 2 Kings 23:25

Daniel Handout #1 Primary Documents Bible: 2 Kings 23:25-25:21; 2 Chronicles 35:1-36:21; Jeremiah 25:1; 46-47, 52; Daniel 1:1-2 D. J. Wiseman, Chronicles of Chaldean Kings, 626-556 B.C. (1956); A. K. Grayson, Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles (2000, new translation with commentary); J. B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET, excerpts) Superscription (Daniel 1:1-2) Jehoiakim, King of Judah Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon [ ← Sandwich ] Jehoiakim, King of Judah Frame (Daniel 1:1 and 21) _________ B.C. [ Bracket ] _________ B.C. Collapse of Assyrian Empire Ashurbanipal II (668-627 B.C.; alternative, 668-631 B.C.) Ashur-etel-ilani (627-623 B.C.; alternative, 631-627 B.C.) Sin-shar-iskun (627-612 B.C.; alternative, 623-612 B.C.) Assur-uballit II (612-?610/09 B.C.) Rise of the Babylonian Empire Nabopolassar (626-605 B.C.) Nebuchadnezzar II/Nebuchadrezzar (605-562 B.C.) Amel-Marduk (=Evil-merodach, 2 Kings 25:27-30) (562-560 B.C.) Neriglissar (560-558 B.C.) Labashi-marduk (557 B.C.) Nabonidus (556-539 B.C.) Co-Regent: Belshazzar (?553-539 B.C.) Contest with Egypt Rise of Saite (26th) Dynasty (664-525 B.C.); Decline of Nubian (25th) Dynasty (716-663 B.C.); Reunion of Upper and Lower Egypt (656 B.C.) Psammetichus I (Psamtik I) (664-610 B.C.) Necho II (610-595 B.C.) Psammetichus II (Psamtik II) (595-589 B.C.) Hophra/Apries (589-570 B.C.) Sandwich of Judah Josiah (640-609 B.C.) Jehohaz (3 months, 609 B.C.; 2 Kings 23:31) Jehoiakim (609-597 B.C.) Jehoiachin (3 months, 596 B.C.; 2 Kings 24:8) Zedekiah (597-586 B.C.) Nabopolassar’s Revolt Against Assyria “son of a nobody”—Nabopolassar cylinder (cf. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

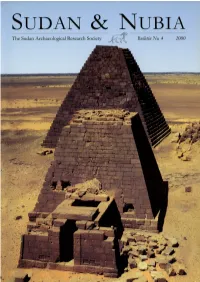

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

I Introduction: History and Texts

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00866-3 - The Meroitic Language and Writing System Claude Rilly and Alex de Voogt Excerpt More information I Introduction: History and Texts A. Historical Setting The Kingdom of Meroe straddled the Nile in what is now known as Nubia from as far north as Aswan in Egypt to the present–day location of Khartoum in Sudan (see Map 1). Its principal language, Meroitic, was not just spoken but, from the third century BC until the fourth century AD, written as well. The kings and queens of this kingdom once proclaimed themselves pha- raohs of Higher and Lower Egypt and, from the end of the third millennium BC, became the last rulers in antiquity to reign on Sudanese soil. Centuries earlier the Egyptian monarchs of the Middle Kingdom had already encountered a new political entity south of the second cataract and called it “Kush.” They mentioned the region and the names of its rulers in Egyptian texts. Although the precise location of Kush is not clear from the earliest attestations, the term itself quickly became associated with the first great state in black Africa, the Kingdom of Kerma, which developed between 2450 and 1500 BC around the third cataract. The Egyptian expansion by the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550–1295 BC) colonized this area, an occupation that lasted for more than five centuries, during which the Kushites lost their independence but gained contact with a civilization that would have a last- ing influence on their culture. During the first millennium BC, in the region of the fourth cataract and around the city of Napata, a new state developed that slowly took over the Egyptian administration, which was withdrawing in this age of decline. -

Buhen in the New Kingdom

Buhen in the New Kingdom George Wood Background - Buhen and Lower Nubia before the New Kingdom Traditionally ancient Egypt ended at the First Cataract of the Nile at Elephantine (modern Aswan). Beyond this lay Lower Nubia (Wawat), and beyond the Dal Cataract, Upper Nubia (Kush). Buhen sits just below the Second Cataract, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite modern Wadi Halfa, at what would have been a good location for ships to carry goods to the First Cataract. The resources that flowed from Nubia included gold, ivory, and ebony (Randall-MacIver and Woolley 1911a: vii, Trigger 1976: 46, Baines and Málek 1996: 20, Smith, ST 2004: 4). Egyptian operations in Nubia date back to the Early Dynastic Period. Contact during the 1st Dynasty is linked to the end of the indigenous A-Group. The earliest Egyptian presence at Buhen may have been as early as the 2nd Dynasty, with a settlement by the 3rd Dynasty. This seems to have been replaced with a new town in the 4th Dynasty, apparently fortified with stone walls and a dry moat, somewhat to the north of the later Middle Kingdom fort. The settlement seems to have served as a base for trade and mining, and royal seals from the 4th and 5th Dynasties indicate regular communications with Egypt (Trigger 1976: 46-47, Baines and Málek 1996: 33, Bard 2000: 77, Arnold 2003: 40, Kemp 2004: 168, Bard 2015: 175). The latest Old Kingdom royal seal found was that of Nyuserra, with no archaeological evidence of an Egyptian settlement after the reign of Djedkara. -

1 Egypt Nov 18 to Dec 7 2019 Nov 18 to 19 a Long Flight from Chicago To

Egypt Nov 18 to Dec 7 2019 Nov 18 to 19 A long flight from Chicago to Amman, then a short flight to Cairo. We were met inside security by the Egitalloyd representative who, with the driver, took us to the Ramses Hilton on the Nile. Our minibus had to pass the soccer stadium, where a big game was about to start, so the roads were jammed. The representative had been with us briefly in 2018, and seemed really happy to see us. At the hotel, we were given a refurbished room with a Nile view, which we love, and non-smoking, but with a shower instead of a tub. Nov. 20 After a short night (from jetlag) and a nice breakfast, we walked the few blocks to the old Egyptian Museum and spent several hours there. A large number of artifacts had been moved out to the new Grand Egyptian Museum, in Giza, for conservation and eventual display, and they were painting and refurbishing the old Egyptian Museum so a lot of sculpture was wrapped and covered in drop cloths. They had done a good job of introducing new areas, in particular the exhibit of artifacts from Yuya and Thuyu’s tomb (which was already set up when we were there in 2018). A special exhibition space had a good exhibit of the El-Gusus Cachette, a tomb of 153 elites, mostly priests and priestesses of Amun, discovered in 1891. We managed to spend time in the protodynastic exhibit, as well. Not surprisingly, we ran into someone we know who was not on our group tour...Tom Hardwick, the curator of Ancient Egyptian art at the Houston Museum of Natural History. -

A Brief Description of the Nobiin Language and History by Nubantood Khalil, (Nubian Language Society)

A brief description of the Nobiin language and history By Nubantood Khalil, (Nubian Language Society) Nobiin language Nobiin (also called Mahas-Fadichcha) is a Nile-Nubian language (North Eastern Sudanic, Nilo-Saharan) descendent from Old Nubian, spoken along the Nile in northern Sudan and southern Egypt and by thousands of refugees in Europe and the US. Nobiin is classified as a member of the Nubian language family along with Kenzi/Dongolese in upper Nubia, Meidob in North Darfur, Birgid in Central and South Darfur, and the Hill Nubian languages in Southern Kordofan. Figure 1. The Nubian Family (Bechhaus 2011:15) Central Nubian Western Northern Nubian Nubian ▪ Nobiin ▪ Meidob ▪ Old Nubian Birgid Hill Nubians Kenzi/ Donglese In the 1960's, large numbers of Nobiin speakers were forcibly displaced away from their historical land by the Nile Rivers in both Egypt and Sudan due to the construction of the High Dam near Aswan. Prior to that forcible displacement, Nobiin was primarily spoken in the region between the first cataract of the Nile in southern Egypt, to Kerma, in the north of Sudan. The following map of southern Egypt and Sudan encompasses the areas in which Nobiin speakers have historically resided (from Thelwall & Schadeberg, 1983: 228). Nubia Nubia is the land of the ancient African civilization. It is located in southern Egypt along the Nile River banks and extends into the land that is known as “Sudan”. The region Nubia had experienced writing since a long time ago. During the ancient period of the Kingdoms of Kush, 1 | P a g e the Kushite/Nubians used the hieroglyphic writing system. -

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Applying a Multi- Analytical Approach to the Investigation of Ancient Egyptian Influence in Nubian Communities: The Socio- Cultural Implications of Chemical Variation in Ceramic Styles Julia Carrano Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Stuart T. Smith Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara George Herbst Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Gary H. Girty Department of Geological Sciences, San Diego State University Carl J. Carrano Department of Chemistry, San Diego State University Jeffrey R. Ferguson Archaeometry Laboratory, Research Reactor Center, University of Missouri Abstract is article reviews published archaeological research that explores the potential of combined chemical and petrographic analyses to distin - guish manufacturing methods of ceramics made om Nile river silt. e methodology was initially applied to distinguish the production methods of Egyptian and Nubian- style vessels found in New Kingdom and Napatan Period Egyptian colonial centers in Upper Nubia. Conducted in the context of ongoing excavations and surveys at the third cataract, ceramic characterization can be used to explore the dynamic role pottery production may have played in Egyptian efforts to integrate with or alter native Nubian culture. Results reveal that, despite overall similar geochemistry, x-ray fluorescence (XRF), instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA), and petrography can dis - tinguish Egyptian and Nubian- -

Edward Lipiński

ROCZNIK ORIENTALISTYCZNY, T. LXIV, Z. 2, 2011, (s. 87–104) EDWARD LIPIŃSKI Meroitic (Review article)1 Abstract Meroitic is attested by written records found in the Nile valley of northern Sudan and dating from the 3rd century B.C. through the 5th century A.D. They are inscribed in a particular script, either hieroglyphic or more often cursive, which has been deciphered, although our understanding of the language is very limited. Basing himself on about fifty words, the meaning of which is relatively well established, on a few morphological features and phonetic correspondences, Claude Rilly proposes to regard Meroitic as a North-Eastern Sudanic tongue of the Nilo-Saharan language family and to classify it in the same group as Nubian (Sudan), Nara (Eritrea), Taman (Chad), and Nyima (Sudan). The examination of the fifty words in question shows instead that most of them seem to belong to the Afro-Asiatic vocabulary, in particular Semitic, with some Egyptian loanwords and lexical Cushitic analogies. The limited lexical material at our disposal and the extremely poor knowledge of the verbal system prevent us from a more precise classification of Meroitic in the Afro-Asiatic phylum. In fact, the only system of classification of languages is the genealogical one, founded on the genetic and historical connection between languages as determined by phonological and morpho-syntactic correspondences, with confirmation, wherever possible, from history, archaeology, and kindred sciences. Meroitic is believed to be the native language of ancient Nubia, attested by written records which date from the 3rd century B.C. through the 5th century A.D. -

An Analysis of Egypt's Foreign Policy During the Saite Period

AN ANALYSIS OF EGYPT'S FOREIGN POLICY DURING THE SAITE PERIOD by JULIEN BOAST A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of MPHIL(B) in EGYPTOLOGY Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham September 2006 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This study consists of an analysis of Egyptian foreign policy during the Saite period (including the reign of Necho I), and also briefly examines the actions of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty in order to establish the correct context. Despite the large gaps in the historical record during this period, judicious use of sources from a number of different cultures allows the historian to attempt to reconstruct the actions of the time, and to discuss possible motivations for them, seeking to identify concerns linking the foreign policy of all the Saite kings. Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council, whose support has been vital in the undertaking of this study. I would also like to thank Dr. -

DISCOVER EGYPT Including Alexandria • December 1-14, 2021

2021 Planetary Society Adventures DISCOVER EGYPT Including Alexandria • December 1-14, 2021 Including the knowledge and use of astronomy in Ancient Egypt! Dear Travelers: The expedition offers an excellent Join us!... as we discover the introduction to astronomy and life extraordinary antiquities and of ancient Egypt and to the ultimate colossal monuments of Egypt, monuments of the Old Kingdom, the December 1-14, 2021. Great Pyramids and Sphinx! It is a great time to go to Egypt as Discover the great stone ramparts the world reawakens after the of the Temple of Ramses II at Abu COVID-19 crisis. Egypt is simply Simbel, built during the New not to be missed. Kingdom, on the Abu Simbel extension. This program will include exciting recent discoveries in Egypt in The trip will be led by an excellent addition to the wonders of the Egyptologist guide, Amr Salem, and pyramids and astronomy in ancient an Egyptologist scholar, Dr. Bojana Egypt. Visits will include the Mojsov fabulous new Alexandria Library Join us!... for a treasured holiday (once the site of the greatest library in Egypt! in antiquity) and the new Alexandria National Museum which includes artifacts from Cleopatra’s Palace beneath the waters of Alexandria Harbor. Mediterranean Sea Alexandria Cairo Suez Giza Bawiti a y i ar is Bah s Oa Hurghada F arafra O asis Valley of Red the Kings Luxor Sea Esna Edfu Aswan EGYPT Lake Nasser Abu Simbel on the edge of the Nile Delta en route. We will first visit the COSTS & CONDITIONS Alexandria National Museum, to see recent discoveries from excavations in the city and its ancient harbors.