Patterns of School Choice: Two Districts in St. Petersburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passport of St. Petersburg Industrial Zones

The Committee for industrial policy and innovation of St. Petersburg Passport of St. Petersburg industrial zones 3-d edition 2015 Contents 1. Preamble..................................................................................................................................................................2 2. Industrial zones of St. Petersburg............................................................................................................................8 2.1. Area of industrial zones...................................................................................................................................9 2.2. Branch specialization of industrial zones according to town-planning regulations of industrial zones..............9 2.3. The Master plan of Saint-Petersburg (a scheme of a functional zoning of St. Petersburg)..............................................................................................10 2.4. The Rules of land use and building of St. Petersburg (a scheme of a territorial zoning of St. Petersburg).............................................................................................12 2.5. Extent of development of territories of industrial zones and the carried-out projects of engineering training of territories of industrial zones............................................................................................................................13 2.6. Documentation of planning areas of the industrial zones........................................................................13 -

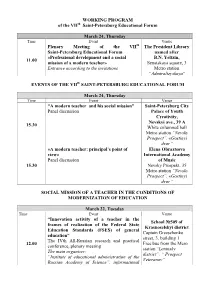

WORKING PROGRAM of the VII Saint-Petersburg Educational

WORKING PROGRAM of the VIIth Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue Plenary Meeting of the VIIth The President Library Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum named after «Professional development and a social B.N. Yeltzin, 11.00 mission of a modern teacher» Senatskaya square, 3 Entrance according to the invitations Metro station “Admiralteyskaya” EVENTS OF THE VIIth SAINT-PETERSBURG EDUCATIONAL FORUM March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue “A modern teacher and his social mission” Saint-Petersburg City Panel discussion Palace of Youth Creativity, Nevskyi ave., 39 A 15.30 White columned hall Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” «A modern teacher: principal’s point of Elena Obraztsova view» International Academy Panel discussion of Music 15.30 Nevsky Prospekt, 35 Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” SOCIAL MISSION OF A TEACHER IN THE CONDITIONS OF MODERNIZATION OF EDUCATION March 22, Tuesday Time Event Venue “Innovation activity of a teacher in the School №509 of frames of realization of the Federal State Krasnoselskyi district Education Standards (FSES) of general Captain Greeschenko education” street, 3, building 1 The IVth All-Russian research and practical 12.00 Free bus from the Mero conference, plenary meeting station “Leninsky The main organizer: district”, “ Prospect “Institute of educational administration of the Veteranov” Russian Academy of Science”, informational and methodological center of Krasnoselskyi district of Saint-Petersburg, School №509 of Krasnoselskyi district March -

Urban Planning

Leonid Lavrov, Elena Molotkova, Andrey Surovenkov — Pages 29–42 ON EVALUATING THE CONDITION OF THE SAINT PETERSBURG HISTORIC CENTER DOI: 10.23968/2500-0055-2020-5-3-29-42 Urban Planning ON EVALUATING THE CONDITION OF THE SAINT PETERSBURG HISTORIC CENTER Leonid Lavrov, Elena Molotkova*, Andrey Surovenkov Saint Petersburg State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering Vtoraja Krasnoarmeyskaya st., 4, Saint Petersburg, Russia *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: This study was prompted by the introduction of the urban environment quality index into the system operated by the Russian Ministry of Construction Industry, Housing and Utilities Sector (Minstroy). We note that the ˝environment-centric˝ methodologies were already worked on and applied to housing studies in Leningrad as far back as during the 1970–1980s, and that the insights from these studies can now be used for analyzing the current state of the urban environment. Purpose of the study and methods: The information reviewed in this article gives us the first glimpse of the tangible urban environment in the historic center of Saint Petersburg. Many features of this part of the city are reminiscent of other European metropolises, but the fact that the historic center is split into three parts by vast waterways, that the construction began from the ground up in the middle of the wilderness, and that the active urban development phase lasted only a century and a half (from the 1760s to the 1910s), has a major part to play. Results: We use quantitative data to describe the features of the Saint Petersburg historic center and compare our findings to the features of European metropolises, across such parameters as spatial geometry, transportation and pedestrian links, and environmental conditions. -

List of the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia for St

List of the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia for St. Petersburg and the Leningrad Region № Units Addresses п\п 1 Admiralteysky District of Saint 190013, Saint Petersburg Vereyskaya Street, 39 Petersburg 2 Vasileostrovsky District of Saint 199106, Saint Petersburg, Vasilyevsky Island, 19th Line, 12a Petersburg 3 Vyborgsky District of Saint 194156, Saint Petersburg, Prospekt Parkhomenko, 18 Petersburg 4 Kalininsky District of Saint 195297, Saint Petersburg, Bryantseva Street, 15 Petersburg 5 Kirovsky District of Saint 198152, Saint Petersburg, Avtovskaya Street, 22 Petersburg 6 Kolpinsky District of Saint 198152, Saint Petersburg, Kolpino, Pavlovskaya Street, 1 Petersburg 7 Krasnogvardeisky District of 195027, Saint Petersburg, Bolsheokhtinsky Prospekt, 11/1 Saint Petersburg 8 Krasnoselsky District of Saint 198329, Saint Petersburg, Tambasova Street, 4 Petersburg 9 Kurortny District of Saint 197706, Saint Petersburg, Sestroretsk, Primorskoe Highway, Petersburg 280 10 Kronshtadtsky District of Saint 197760, Saint Petersburg, Kronstadt, Lenina Prospekt, 20 Petersburg 11 Moskovsky District of Saint 196135, Saint Petersburg, Tipanova Street, 3 Petersburg 12 Nevsky District of Saint 192171, Saint Petersburg, Sedova Street, 86 Petersburg 13 Petrogradsky District of Saint 197022, Saint Petersburg, Grota Street, 1/3 Petersburg 14 Petrodvortsovy District of Saint 198516, Saint Petersburg, Peterhof, Petersburg Konnogrenaderskaya Street., 1 15 Primorsky District of Saint 197374 Saint Petersburg, Yakhtennaya Street, 7/2 -

Doing Business in St. Petersburg St

Doing business in St. Petersburg St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development – member of Enterprise Europe Network | www.doingbusiness.ru 1 Doing business in St. Petersburg Guide for exporters, investors and start-ups The current publication was developed by and under supervision of Enterprise Europe Network - Russia, Gate2Rubin Consortium, Regional Center - St. Petersburg operated by St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development with the assistance of the relevant legal, human resources, certification, research and real estate firms. © 2014 Enterprise Europe Network - Russia, Gate2Rubin Consortium, Regional Center – St. Petersburg operated by St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development. All rights reserved. International copyright. Any use of materials of this publication is possible only after written agreement of St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development and relevant contributing firms. Doing business in St. Petersburg. – Spb.: Politekhnika-servis, 2014. – 167 p. ISBN 978-5-906555-22-9 Online version available at www.doingbusiness.ru. Doing business in St. Petersburg 2 St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development – member of Enterprise Europe Network | www.doingbusiness.ru Table of contents 1. The city ....................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Geography ............................................................................................................................. 6 1.2. Public holidays and business hours ...................................................................................... -

St Petersburg Bypass [EBRD

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION OF THE ST. PETERSBURG BY-PASS SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 GENERAL INFORMATION This document covers a brief description of matters related to environmental protection (EP) during the planning, design and construction of the St.Petersburg By- Pass. Ecological Impact Assessment Report sections (EIAR) were prepared during the stage of engineering design, which obtained all the necessary approvals. 1.2 THE NEED FOR THE INVESTMENT To accelerate construction on the basis of the Program of development of the road network "Roads of Russia of XXI century", which was reviewed and approved at the session of the RF Government dated June 28, 2001, the Government of Russian Federation issued directions aimed at speeding up construction of this project. The construction of the By-Pass will divert a considerable part of traffic beyond the borders of the built up areas and thus improve the environmental situation in St.Petersburg by decreasing the traffic volume and increasing the traffic speed. 1.3 BASIC LEGISLATIVE ACTS REGULATING THE USE AND PROTECTION OF CERTAIN KINDS OF RESOURCES S The law of the RSFSR "Protection of environment" of December 19, 1991 (amended by Laws of the Russian Federation of 21 February 1992 No.2397-1, 2 June 1993 No.5076-1, 10 June 2001 No. 93-FZ, 27 December 2000 No. 150-FZ, 30 December 2001 No. 194-FZ, 30 December 2001 No. 196-FZ); 1 S Water Code of the Russian Federation of November 16, 1995. No.167-FZ (amended by Federal Law of 30 December 2001 No. -

Valuation Report PO-36/2017

Valuation Report PO-36/2017 A portfolio of real estate assets in Russia (St Petersburg, Moscow, Yekaterinburg) and Germany (Leipzig, Landshut, Munich) Prepared on behalf of LSR Group OJSC Date of issue: March 12, 2018 Contact details LSR Group OJSC, 15-H, liter Ǩ, 36, Kazanskaya St, St Petersburg, 190031, Russia Lyudmila Fradina, Tel. +7 812 3856106, [email protected] Knight Frank Saint-Petersburg AO, Liter A, 3B, Mayakovskogo St., St Petersburg, 191025, Russia Svetlana Shalaeva, Tel. +7 812 3632222, [email protected] Valuation report Ň A portfolio of real estate assets in St. Petersburg and Leningradskaya Oblast', Moscow and Moskovskaya Oblast’, Yekaterinburg, Russia and Leipzig, Landshut and Munich, Germany Ň KF Ref: PO-36/2017 Ň Prepared on behalf of LSR Group OJSC Ň Date of issue: March 12, 2018 Page 1 Executive summary The executive summary below is to be used in conjunction with the valuation report to which it forms part and, is subject to the assumptions, caveats and bases of valuation stated herein. It should not be read in isolation. Location The Properties within the Portfolio of real estate assets to be valued are located in St. Petersburg and Leningradskaya Oblast', Moscow, Yekaterinburg, Russia and in Munich, Leipzig and Landshut, Germany. Description The Subject Property is represented by vacant, partly or completely developed land plots intended for residential and commercial development and commercial office buildings with related land plots. Areas Ɣ Buildings – see the Schedule of Properties below Ɣ Land plots – see the Schedule of Properties below Tenure Ɣ Buildings – see the Schedule of Properties below Ɣ Land plots – see the Schedule of Properties below Tenancies As of the valuation date from the data provided by the Client, the office properties are partially occupied by the short-term leaseholders according to the lease agreements. -

Spbu STUDENT GUIDE

SPbU STUDENT GUIDE english.spbu.ru1 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. ABOUT ST PETERSBURG UNIVERSITY 2.1. The University in numbers 2.2. Overview 3. BEFORE ARRIVAL 3.1. Visa 3.2. Medical insurance 3.3. Document preparation 3.4. How to get to your destination after arriving in St Petersburg 4. AFTER ARRIVAL 4.1. Document processing 4.2. If you have any questions about your studies 4.3. Migration registration of foreign citizens – processing of documents necessary for staying in St Petersburg 4.4. Accommodation in a hall of residence 4.5. Tuition payment 5. STUDIES 5.1. Where to see the timetable 5.2. Single user login 5.3. Resources for studying: the Research Park and the Library 5.4. What are the reasons for being expelled? 5.5. Feedback 6. STUDENT EXCHANGE PROGRAMMES 6.1. How to participate in the academic mobility programme 6.2. What programmes exist 6.3. How to apply 6.4. Contact details 2 CONTENTS 7. SCHOLARSHIPS AND COMPETITIONS 7.1. Types of scholarships 7.2. How to get an increased or personal/notable scholarship 7.3. Alumni Association Scholarship 7.4. Endowment Fund Scholarship 7.5. The ‘SPbU Start-up’ contest 7.6. Olympiads 8. OPPORTUNITIES PROVIDED BY THE UNIVERSITY 8.1. Learn Russian in non-degree programmes 8.2. Language testing 8.3. Online courses 8.4. Public lectures 8.5. Volunteering 8.6. Green Campus 8.7. Sports 8.8. Creativity 9. STUDENT ASSOCIATIONS 9.1. The International Student Club 9.2. Erasmus Student Network at St Petersburg University (ESN SPbU) 9.3. -

Russian Defense Business Directory : St. Petersburg

C 57.121: R 92/996 Prepared by: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Bureau of Export Administration ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of many individuals, agencies and companies to the Directory. The author especially wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Robert May, Dale Slaght, Rich Steffens and Karen Zens of the U.S. & Foreign Commercial Service in Russia and Don Stanton of the Bureau of Export Administration for their contributions. Additional copies of this document*, as well as future installments, may be obtained for a nominal fee from: National Technical Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 Phone: (703) 487-4650, Fax: (703) 321 8547, Telex: 64617 COMNTIS. E-mail: [email protected], Internet: http:Wwww.ntis.gov Order by Publication Number(s): Fifth installment (paper copy): PB96-100177 Copies of the Directory are also available from the: Department of Commerce Economic Bulletin Board (EBB): The Directory highlights and enterprise profiles are available in electronic format through the Department of Commerce's Economic Bulletin Board (EBB). Located under "Defense Conversion Subcommittee Information for Russia and the NIS" (Area 20 on the EBB). For more information regarding access or use, call EBB Info/Help line at (202) 4824986 . National Trade Data Bank: A CD-ROM version of the cumulative version is available in the current edition of the National Trade Data Bank (NTDB) at a cost of $59.00 or annual subscription of $575.00. NTDB's phone number is (202) 482-1986, e-mail: [email protected]. Internet: httpWwww.stat-usa.gov Points of contact for changes and updates to information in the Directory: Franklin J. -

Passport of St. Petersburg

Passport of St. Petersburg Saint Petersburg (St. Petersburg) is situated at the easternmost tip of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea. The exact geographical coordinates of the city centre are 59°57' North Latitude 30°19' East Longitude. St. Petersburg, located in the node of several major sea, river and land transportation routes, is the European gate of Russia and its strategic centre closest to the border with the European Union. Inland waters constitute about 10% of the city territory. The total area (with administrative subjects) covers 1439 km². The population amounts to 5 225.7 people (as of January 1, 2016 by the data from the federal statistical agency “Petrostat”). St. Petersburg is the second (after Moscow) largest city of the Russian Federation and the third (after Moscow and London) largest city in Europe. St. Petersburg is the administrative centre of the Northwestern Federal Region which is characterized by considerable potential in natural resources, well developed industry, a fine traffic network and furthermore provides contact of the Russian Federation with the outside world via the sea ports of the Baltic Sea and the Arctic Ocean. The city hosts the following institutions: • The Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation; • Regional offices of federal ministries and departments; • Representations of 24 entities and 2 cities in the Russian Federation; • 65 consular offices of foreign countries; • Offices of international organizations: CIS Inter-Parliamentary Assembly, Inter-Parliamentary Assembly of the Eurasian Economic Community, representatives of international organizations, funds and associations, UN agencies and representative offices and branches of international banks. • Offices of international cultural institutions: the Goethe German Cultural Center, the French Institute, the Finnish Institute, the Dutch Institute, the Danish Cultural Institute, the Israeli Cultural Center and the Italian Cultural Institute. -

Social Geography and Regional Sociology

SOCIAL GEOGRAPHY AND REGIONAL SOCIOLOGY SOCIO-SPATIAL DIFFERENTIATION IN TRANSITION: A PRELIMINARY COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF POST-SOVIET SAINT PETERSBURG AND RIGA D. V. Zhitin a Z. Krisjane b G. Sechi b M. Berzins b a Saint Petersburg State University Received 18 September 2019 7—9 Universitetskaya emb., Saint Petersburg, Russia, 199034 doi: 10.5922/2079-8555-2020-1-6 b University of Latvia © Zhitin D. V., Sechi G., Krisjane Z., 19 Raina boulevard, Riga, Latvia, LV-1050 Berzins M. , 2020 Research into the socio-spatial dynamics in Central-Eastern European cities is an im- portant area of contemporary transition studies. Open issues in this domain range from defining a theoretical framework to data availability and methodological approaches. As to the former aspect, recent literature focuses on the hybrid nature of the post-socialist urban space, which underwent transformation in the conditions of globalization and eco- nomic liberalization; the earlier model of spatial development changed dramatically as a result. The multi-scalar and comparative approaches may shed new light on the complex patterns of urban socio-spatial differentiation and its post-Soviet dynamics. Growing regional socio-economic imbalances observed in the former socialist states are lending new urgency to this area of research. This study employs a comparative approach to investigate post-1991 socio-spatial trans- formations in St Petersburg and Riga — the two largest post-Soviet urban centres in the Baltic Sea region. An important result of the research is a methodology for multi-leva- el analysis of changes in the urban environment of post-socialist cities. Data from post-1991 national censuses and population registers are used to calculate measures of social well-being in urban districts as well as to identify territorial imbalances. -

How to Invest in the Industry in Saint Petersburg

The Committee for industrial policy and innovation of St. Petersburg How to invest in the industry in Saint Petersburg 2-d edition | 2015 «HOW TO INVEST IN THE INDUSTRY IN SAINT PETERSBURG» Dear friends! I am glad to welcome the readers of the guide “How to Machines, Admiralteiskie Verfi, Klimov, Concern “Al- invest in the industry in St. Petersburg”. maz – Antey”, “Toyota”, “Hyundai”, “Nissan”, “Novar- St. Petersburg is one of the largest industrial, scien- tis”, “Siemens”, “Bosch”, “Otis”, tific and cultural centers of Russia. Our city is actively Fazer, Heineken and many others. developing such an important sector of the economy Due to the advantageous terms that we offer to as shipbuilding, energy and heavy engineering, auto- investors there are a growing number of residents of motive and pharmaceutical cluster. the Special economic zones, technology parks and To competitive advantages of St. Petersburg is a business incubators, new industrial complexes and unique geographical location, skilled workforce, devel- innovative enterprises in St. Petersburg. oped infrastructure, access to key markets of Russia I invite to St Petersburg of all who aspire to reach new and the European Union, tax and other preferences for heights in business. the investors and operating companies. I am confident that the guide will become your reliable St. Petersburg’s investment climate is considered one source of information and guide in the business world of the best in the country. City Government pays great of the Northern capital. attention to the support and maintenance of invest- ment projects. Welcome to St. Petersburg! St. Petersburg for many years cooperates with the largest Russian and foreign investors.