Urban Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORKING PROGRAM of the VII Saint-Petersburg Educational

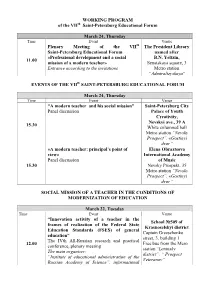

WORKING PROGRAM of the VIIth Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue Plenary Meeting of the VIIth The President Library Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum named after «Professional development and a social B.N. Yeltzin, 11.00 mission of a modern teacher» Senatskaya square, 3 Entrance according to the invitations Metro station “Admiralteyskaya” EVENTS OF THE VIIth SAINT-PETERSBURG EDUCATIONAL FORUM March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue “A modern teacher and his social mission” Saint-Petersburg City Panel discussion Palace of Youth Creativity, Nevskyi ave., 39 A 15.30 White columned hall Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” «A modern teacher: principal’s point of Elena Obraztsova view» International Academy Panel discussion of Music 15.30 Nevsky Prospekt, 35 Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” SOCIAL MISSION OF A TEACHER IN THE CONDITIONS OF MODERNIZATION OF EDUCATION March 22, Tuesday Time Event Venue “Innovation activity of a teacher in the School №509 of frames of realization of the Federal State Krasnoselskyi district Education Standards (FSES) of general Captain Greeschenko education” street, 3, building 1 The IVth All-Russian research and practical 12.00 Free bus from the Mero conference, plenary meeting station “Leninsky The main organizer: district”, “ Prospect “Institute of educational administration of the Veteranov” Russian Academy of Science”, informational and methodological center of Krasnoselskyi district of Saint-Petersburg, School №509 of Krasnoselskyi district March -

Comparing Two Key Modernist Public Squares Among Athens & Stockholm

DEGREE PROJECT IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT, SECOND CYCLE, 15 CREDITS STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2017 Comparing two key modernist public squares among Athens & Stockholm From similar morphological patterns to common urban experience IOLI APOSTOLOPOULOU KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT TRITA SoM EX 2017-26 www.kth.se Fig.1, Sergels Torg, by Gunnar Smoliansky in 1978 Acknowledgement I would like to sincerely thank Prof. Tigran Haas for his support and guidance throughout the master program, as well as Ax:son Johnson Foun- dation and Royal Institute of Technology for funding the program. I would like to express my gratitude to Ryan Locke for his contribution as a supervisor and for encouraging me to explore the wide variety of topics related to Urbanism. In addition, I would like to thank Jaimes Montes for his initial contribu- tion to my research. Finally I would like to thank my family and especially my brother Nikolaos for supporting me during my studies. Ioli Apostolopoulou 3 CONTENTS Abstract...............................................................................................................................................6 Introduction........................................................................................................................7 Preface................................................................................................................................................7 Research Purpose and Question......................................................................................................7 -

Cultural Heritage, Cinema, and Identity by Kiun H

Title Page Framing, Walking, and Reimagining Landscapes in a Post-Soviet St. Petersburg: Cultural Heritage, Cinema, and Identity by Kiun Hwang Undergraduate degree, Yonsei University, 2005 Master degree, Yonsei University, 2008 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2019 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Kiun Hwang It was defended on November 8, 2019 and approved by David Birnbaum, Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of History of Art & Architecture Vladimir Padunov, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures Dissertation Advisor: Nancy Condee, Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures ii Copyright © by Kiun Hwang 2019 Abstract iii Framing, Walking, and Reimagining Landscapes in a Post-Soviet St. Petersburg: Cultural Heritage, Cinema, and Identity Kiun Hwang, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2019 St. Petersburg’s image and identity have long been determined by its geographical location and socio-cultural foreignness. But St. Petersburg’s three centuries have matured its material authenticity, recognizable tableaux and unique urban narratives, chiefly the Petersburg Text. The three of these, intertwined in their formation and development, created a distinctive place-identity. The aura arising from this distinctiveness functioned as a marketable code not only for St. Petersburg’s heritage industry, but also for a future-oriented engagement with post-Soviet hypercapitalism. Reflecting on both up-to-date scholarship and the actual cityscapes themselves, my dissertation will focus on the imaginative landscapes in the historic center of St. -

The Role of the Local Host Community's Involvement in the Development of Tourism: a Case Study of the Residents' Perception

sustainability Article The Role of the Local Host Community’s Involvement in the Development of Tourism: A Case Study of the Residents’ Perceptions toward Tourism on the Route of Santiago de Compostela (Spain) Jakson-Renner-Rodrigues Soares 1,2,* , Maria-Francisca Casado-Claro 3, María-Elvira Lezcano-González 4, María-Dolores Sánchez-Fernández 1 , Larissa-Paola-Macedo-Castro Gabriel 5 and Maria Abríl-Sellarés 6 1 Department of Business, University of A Coruña, 15001 A Coruña, Spain; [email protected] 2 Master in Tourism Business Management, Universidade Estadual do Ceará, Fortaleza 60714-903, Brazil 3 Department of Economics and Business, Universidad Europea, 28670 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 4 Department of Humanities, University of A Coruña, 15001 A Coruña, Spain; [email protected] 5 Tourism, Economy and Sustainability Research Group, Universidade Estadual do Ceará, Fortaleza 60714-903, Brazil; [email protected] 6 Department of Tourism, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Citation: Soares, J.-R.-R.; Casado-Claro, M.-F.; Lezcano-González, Abstract: As an economic, social, and cultural activity, tourism shapes the relationship between M.-E.; Sánchez-Fernández, M.-D.; visitors and local communities in tourist destinations. While tourism generates economic growth and Gabriel, L.-P.-M.-C.; Abríl-Sellarés, M. employment opportunities for residents, its benefits come with a social cost. This article highlights The Role of the Local Host the results of an online survey that was carried out at the beginning of 2021 in the seven major Community’s Involvement in the Galician cities along the Route of Santiago de Compostela (the Way of St. -

List of the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia for St

List of the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia for St. Petersburg and the Leningrad Region № Units Addresses п\п 1 Admiralteysky District of Saint 190013, Saint Petersburg Vereyskaya Street, 39 Petersburg 2 Vasileostrovsky District of Saint 199106, Saint Petersburg, Vasilyevsky Island, 19th Line, 12a Petersburg 3 Vyborgsky District of Saint 194156, Saint Petersburg, Prospekt Parkhomenko, 18 Petersburg 4 Kalininsky District of Saint 195297, Saint Petersburg, Bryantseva Street, 15 Petersburg 5 Kirovsky District of Saint 198152, Saint Petersburg, Avtovskaya Street, 22 Petersburg 6 Kolpinsky District of Saint 198152, Saint Petersburg, Kolpino, Pavlovskaya Street, 1 Petersburg 7 Krasnogvardeisky District of 195027, Saint Petersburg, Bolsheokhtinsky Prospekt, 11/1 Saint Petersburg 8 Krasnoselsky District of Saint 198329, Saint Petersburg, Tambasova Street, 4 Petersburg 9 Kurortny District of Saint 197706, Saint Petersburg, Sestroretsk, Primorskoe Highway, Petersburg 280 10 Kronshtadtsky District of Saint 197760, Saint Petersburg, Kronstadt, Lenina Prospekt, 20 Petersburg 11 Moskovsky District of Saint 196135, Saint Petersburg, Tipanova Street, 3 Petersburg 12 Nevsky District of Saint 192171, Saint Petersburg, Sedova Street, 86 Petersburg 13 Petrogradsky District of Saint 197022, Saint Petersburg, Grota Street, 1/3 Petersburg 14 Petrodvortsovy District of Saint 198516, Saint Petersburg, Peterhof, Petersburg Konnogrenaderskaya Street., 1 15 Primorsky District of Saint 197374 Saint Petersburg, Yakhtennaya Street, 7/2 -

Guidelines for Owners of Small Vessels, Pleasure Craft and Sport Sailboats

GUIDELINES FOR OWNERS OF SMALL VESSELS, PLEASURE CRAFT AND SPORT SAILBOATS Contents CHAPTER 1. Tourist routes along the waterways of the North-West of Russia. .............. 6 CHAPTER 2. Yacht clubs having guest berths ................................................................ 10 CHAPTER 3. Specifics of navigation in certain areas of waterways ............................... 12 3.1.1. Navigation in the border area of the Russian Federation. ...................................... 12 3.1.2. Pleasure craft navigation on the Saimaa Canal. .................................................... 13 3.1.3. Navigation of small vessels and yachts in Vyborg Bay. ........................................ 14 3.1.4. Navigation of small vessels and yachts the water area of Saint Petersburg. .......... 15 3.1.5. Procedure for entry of vessels to the sea ports Big Port of Saint Petersburg and Passenger Port of Saint Petersburg. ................................................................................ 18 CHAPTER 4. Procedures for customs and border control and customs operations ......... 19 4.1. Regulatory and legal framework. ............................................................................. 19 4.2. Specifics of control operations to check the grounds for passing the state border by Russian and foreign small vessels, sport sailboats and pleasure craft ............................. 22 4.3. Procedure for the passage of ships in the HMCP of the sea port Big Port of Saint Petersburg (terminal for servicing small vessels, sport sailboats -

Moscow and St Petersburg

Creating a ‘Public’ in St Petersburg, 1703-1761 Paul Keenan School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UCL Ph.D. History 1 UMI Number: U592953 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592953 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract The thesis deals with the creation of a ‘public’ in St Petersburg during the first half of the eighteenth century. The term ‘public’ has generated a considerable historiography dealing with its implications for the field of eighteenth-century studies, which are discussed in the introduction along with the contemporary definitions of the word. In eighteenth-century Russia, the term ‘public’ usually carried the meaning of ‘audience’, typically in reference to the theatre and other spectacles. The definition of this and other similar terms provides an important framework through which to analyse the various elements of this phenomenon. This analysis has centred on the city of St Petersburg in this period for several reasons. Firstly, it was the seat of both the Russian government and the Court around a decade after its foundation and Peter I ensured its rapid population. -

Planning Latin America's Capital Cities

«o Planning Latin America’s Capital Cities, 1850-1950 cs edited by Arturo Almandoz First published 2002 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge, 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group © 2002 Selection and editorial matter: Arturo Almandoz; individual chapters: the contributors Typeset in Garamond by PNR Design, Didcot, Oxfordshire Printed and bound in Great Britain by St Edmundsbury Press, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk This book was commissioned and edited by Alexandrine Press, Oxford All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any informa tion storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept legal responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library o f Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalog record for this book has been requested ISBN 0-415-27265-3 ca Contents *o Foreword by Anthony Sutcliffe vii The Contributors ix Acknowledgements xi 1 Introduction 1 Arturo Almandoz 2 Urbanization and Urbanism in Latin America: from Haussmann to CIAM 13 Arturo Almandoz I CAPITALS OF THE BOOMING ECONOMIES 3 Buenos Aires, A Great European City 45 Ramón Gutiérrez 4 The Time of the Capitals. -

Monuments of the World Cultural Heritage in Russia - Challenges and Perspectives» and Annual Conference of the National Committee ICOMOS, Russia

II International Scientific Symposium «Monuments of the World Cultural Heritage in Russia - challenges and perspectives» and Annual Conference of the National Committee ICOMOS, Russia ABSTRACTS 19-21 September 2018 Veliky Novgorod Putting a Stop to Losses, Managing the Present and the Future of the Cultural Heritage of Russia The bitter news of the fire that destroyed the wooden tent-roofed Church of the Assumption in Kondopoga, the Republic of Karelia has shocked all of us. It was a symbol of the spiritual and material power of the Russian people, a cultural monument of federal significance, an object of worship for thousands of people. Its beauty and sophistication, its unique image celebrated by poets and artists were fascinating. Numerous monographs both in Russia and abroad have been dedicated to it, for centuries it was passing down the generations the inimitable charm of the Russian North. This loss is irreversible, architectural monuments may not be cloned. It is imperative to put a stop to losing the masterpieces of the wooden architecture in which Russia used to be so rich. The VII Parliamentary Forum in June 2018 in Suzdal dedicated to this most fragile part of our cultural heritage has raised the issue of the necessity to ensure the safety of the cultural heritage object's that are located far from populated places, in the hard to access areas which was historically predetermined. Russia possesses a unique experience in protecting the objects of the national significance. Vandalizing priceless cultural masterpieces is a kind of terrorism which our country prevails. In our opinion, the state should adopt a comprehensive inter-agency program for protection of the cultural heritage of the Russian North, Siberia and Far East. -

Doing Business in St. Petersburg St

Doing business in St. Petersburg St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development – member of Enterprise Europe Network | www.doingbusiness.ru 1 Doing business in St. Petersburg Guide for exporters, investors and start-ups The current publication was developed by and under supervision of Enterprise Europe Network - Russia, Gate2Rubin Consortium, Regional Center - St. Petersburg operated by St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development with the assistance of the relevant legal, human resources, certification, research and real estate firms. © 2014 Enterprise Europe Network - Russia, Gate2Rubin Consortium, Regional Center – St. Petersburg operated by St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development. All rights reserved. International copyright. Any use of materials of this publication is possible only after written agreement of St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development and relevant contributing firms. Doing business in St. Petersburg. – Spb.: Politekhnika-servis, 2014. – 167 p. ISBN 978-5-906555-22-9 Online version available at www.doingbusiness.ru. Doing business in St. Petersburg 2 St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development – member of Enterprise Europe Network | www.doingbusiness.ru Table of contents 1. The city ....................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Geography ............................................................................................................................. 6 1.2. Public holidays and business hours ...................................................................................... -

The Way of Saint James

The Way of Saint James www.spain.info CONTENTS Introduction 3 The routes 5 French Route Northern Route Primitive Route Other routes How to travel the Way of Saint James 18 On foot By bike On horseback By sailing boat Practical information 23 Where to stay Gastronomy along the Way of Saint James Ministry of Industry, Trade and Tourism Published by: © Turespaña Created by: Lionbridge NIPO: FREE COPY The content of this leaflet has been created with utmost care. However, if you find an error, please help us to improve by sending an email to [email protected] Back cover: Santiago Cathedral, Santiago de Compostela 2 INTRODUCTION Have an unforgettable adventure on the terest in history, art and nature and sport Way of Saint James. Put on your boots, all converge. Whatever your reasons, get on your bike or even take a sailing we can assure you that the experience is boat, which is the most recently adopted worthwhile. method, and discover Spain in a differ- On the Jacobean Route, as the Way of ent way. Take up the challenge of com- Saint James is also known, you will enjoy pleting an ancient route included on the the great cuisine of northern Spain on a UNESCO World Heritage List. You will culinary tour full of things to tempt your travel through incredible natural spaces appetite. and visit towns full of history before reach- ing your goal, Santiago de Compostela. This city in Galicia, where the remains of On your way you will travel the apostle Saint James the Elder rest, re- ceives thousands of pilgrims every year. -

Valuation Report PO-36/2017

Valuation Report PO-36/2017 A portfolio of real estate assets in Russia (St Petersburg, Moscow, Yekaterinburg) and Germany (Leipzig, Landshut, Munich) Prepared on behalf of LSR Group OJSC Date of issue: March 12, 2018 Contact details LSR Group OJSC, 15-H, liter Ǩ, 36, Kazanskaya St, St Petersburg, 190031, Russia Lyudmila Fradina, Tel. +7 812 3856106, [email protected] Knight Frank Saint-Petersburg AO, Liter A, 3B, Mayakovskogo St., St Petersburg, 191025, Russia Svetlana Shalaeva, Tel. +7 812 3632222, [email protected] Valuation report Ň A portfolio of real estate assets in St. Petersburg and Leningradskaya Oblast', Moscow and Moskovskaya Oblast’, Yekaterinburg, Russia and Leipzig, Landshut and Munich, Germany Ň KF Ref: PO-36/2017 Ň Prepared on behalf of LSR Group OJSC Ň Date of issue: March 12, 2018 Page 1 Executive summary The executive summary below is to be used in conjunction with the valuation report to which it forms part and, is subject to the assumptions, caveats and bases of valuation stated herein. It should not be read in isolation. Location The Properties within the Portfolio of real estate assets to be valued are located in St. Petersburg and Leningradskaya Oblast', Moscow, Yekaterinburg, Russia and in Munich, Leipzig and Landshut, Germany. Description The Subject Property is represented by vacant, partly or completely developed land plots intended for residential and commercial development and commercial office buildings with related land plots. Areas Ɣ Buildings – see the Schedule of Properties below Ɣ Land plots – see the Schedule of Properties below Tenure Ɣ Buildings – see the Schedule of Properties below Ɣ Land plots – see the Schedule of Properties below Tenancies As of the valuation date from the data provided by the Client, the office properties are partially occupied by the short-term leaseholders according to the lease agreements.