The Concept of Self-Reflexive Intertextuality in the Works of Umberto Eco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

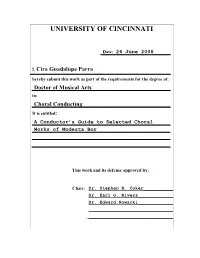

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 26 June 2006 I, Cira Guadalupe Parra hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Choral Conducting It is entitled: A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Stephen R. Coker___________ Dr. Earl G. Rivers_____________ Dr. Edward Nowacki_____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Ensembles and Conducting Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Cira Parra 620 Clinton Springs Ave Cincinnati, Ohio 45229 [email protected] B.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1987 M.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1989 Committee Chair: Stephen R. Coker ABSTRACT Modesta Bor (1926-98) was one of the outstanding Venezuelan composers, conductors, music educators and musicologists of the twentieth century. She wrote music for orchestra, chamber music, piano solo, piano and voice, and incidental music. She also wrote more than 95 choral works for mixed voices and 130 for equal-voice choir. Her style is a mixture of Venezuelan nationalism and folklore with European traits she learned in her studies in Russia. Chapter One contains a historical background of the evolution of Venezuelan art music since the colonial period, beginning in 1770. Knowing the state of art music in Venezuela helps one to understand the unusual nature of the Venezuelan choral movement that developed in the first half of the twentieth century. -

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY

Canadian Movie Channel APPENDIX 4C POTENTIAL INVENTORY CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CANADIAN FEATURE FILMS, FEATURE DOCUMENTARIES AND MADE-FOR-TELEVISION FILMS, 1945-2011 COMPILED BY PAUL GRATTON MAY, 2012 2 5.Fast Ones, The (Ivy League Killers) 1945 6.Il était une guerre (There Once Was a War)* 1.Père Chopin, Le 1960 1946 1.Canadians, The 1.Bush Pilot 2.Désoeuvrés, Les (The Mis-Works)# 1947 1961 1.Forteresse, La (Whispering City) 1.Aventures de Ti-Ken, Les* 2.Hired Gun, The (The Last Gunfighter) (The Devil’s Spawn) 1948 3.It Happened in Canada 1.Butler’s Night Off, The 4.Mask, The (Eyes of Hell) 2.Sins of the Fathers 5.Nikki, Wild Dog of the North 1949 6.One Plus One (Exploring the Kinsey Report)# 7.Wings of Chance (Kirby’s Gander) 1.Gros Bill, Le (The Grand Bill) 2. Homme et son péché, Un (A Man and His Sin) 1962 3.On ne triche pas avec la vie (You Can’t Cheat Life) 1.Big Red 2.Seul ou avec d’autres (Alone or With Others)# 1950 3.Ten Girls Ago 1.Curé du village (The Village Priest) 2.Forbidden Journey 1963 3.Inconnue de Montréal, L’ (Son Copain) (The Unknown 1.A tout prendre (Take It All) Montreal Woman) 2.Amanita Pestilens 4.Lumières de ma ville (Lights of My City) 3.Bitter Ash, The 5.Séraphin 4.Drylanders 1951 5.Have Figure, Will Travel# 6.Incredible Journey, The 1.Docteur Louise (Story of Dr.Louise) 7.Pour la suite du monde (So That the World Goes On)# 1952 8.Young Adventurers.The 1.Etienne Brûlé, gibier de potence (The Immortal 1964 Scoundrel) 1.Caressed (Sweet Substitute) 2.Petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre, La (Little Aurore’s 2.Chat dans -

A Double Détournement in the Classroom: HK Protest Online Game As Conceptual Art

A Double Détournement in the Classroom: HK Protest Online Game as Conceptual Art James Shea Department of Humanities and Creative Writing, Hong Kong Baptist University [email protected] Abstract law professor and co-director of the Center for Law and Intellectual Property at Texas A&M University School of This paper examines the role of digital détournement during Law: Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement in late 2014 through the prism of HK Protest Online Game, a conceptual art game made “They drafted the legislation so broadly that it in response to Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests. Created covers most of the activities the netizens have by an undergraduate Hong Kong student, this work invites a critical reflection on playability by questioning the relationship been doing…Just saying ‘we’re not going to between videogames, play, and “real time” violence. As an prosecute you’ doesn’t address the concerns of unplayable game, it reroutes the player to contemporaneous the netizens. Most people now interpret this as street demonstrations in Hong Kong, serving both as a something that targets their freedom of speech.” détournement of police aggression and of videogames that [4] commercialize violence. Reversing our expectation of games as playful and political action as non-playful, HKPOG presents its What are the implications for creating digital game as unreal and posits Hong Kong’s protests as sites of artwork, including art games, that “plays” with source play. The paper considers related digital artwork and the use of texts, such as digital détournement, if such forms are détournement during the Umbrella Movement, including umbrellas themselves and digitalized “derivative works” also restricted or prohibited in Hong Kong? The bills lacks a known as “secondary creation” (yihchi chongjok in Cantonese clear exemption for “fair use” or “user-generated and èrcì chuàngzuò in Mandarin; 二次創作). -

Eco and Popular Culture Norma Bouchard

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85209-8 - New Essays on Umberto Eco Edited by Peter Bondanella Excerpt More information chapter 1 Eco and popular culture Norma Bouchard Since the beginning of his long and most distinguished career, Umberto Eco has demonstrated an equal devotion to the high canon of Western literature and to popular, mass-produced and mass-consumed, artifacts. Within Eco’s large corpus of published works, however, it is possible to chart different as well as evolving evaluations of the aesthetic merit of both popular and high cultural artifacts. Because such evaluations belong to a corpus that spans from the 1950s to the present, they necessarily reflect the larger epistemological changes that ensued when the resistance to commercialized mass culture on the part of an elitist, aristocratic strand of modern art theory gave way to a postmodernist blurring of the divide between different types of discourses. Yet, it is also crucial to remem- ber that, from his earlier publications onwards, Eco has approached the cultural field as a vast domain of symbolic production where high- and lowbrow arts not only coexist, but also are both complementary and sometimes interchangeable. This holistic understanding of the cultural field explains Eco’s earlier praise of selected popular works amidst a pleth- ora of negative evaluations, as well as his later fictional practice of cita- tions and replays that shapes his work as best-selling novelist of The Name of the Rose (1980), followed by Foucault’s Pendulum (1988), The Island of the Day Before (1994), Baudolino (2000), and The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana (2004). -

RAR, Volume 32, 2017

The RUTGERS ART REVIEW The Journal of Graduate Research in Art History Volume 32 2017 The RUTGERS ART REVIEW Published by the Graduate Students of the Department of Art History Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Volume 32 2017 iii Copyright © 2017 Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey All rights reserved iv Rutgers Art Review Volume 32 Editors Stephen Mack, Kimiko Matsumura, and Hannah Shaw Editorial Board Mary Fernandez James Levinsohn Sophie Ong Kathleen Pierce Negar Rokhgar Faculty Advisor John Kenfeld First published in 1980, Rutgers Art Review (RAR) is an annual open-access journal produced by graduate students in the Department of Art History at Rutgers University. Te journal is dedicated to presenting original research by graduate students in art history and related felds. For each volume the editors convene an editorial board made up of students from the department and review all new submissions. Te strongest papers are then sent to established scholars in order to confrm that each one will contribute to existing scholarship. Articles appearing in Rutgers Art Review, ISSN 0194-049X, are abstracted and indexed online within the United States in History and Life, ARTbibliographies Modern, the Avery Index to Architectural Periodi- cals, BHA (Bibliography of the History of Art), Historical Abstracts, and the Wilson Art Index. In 2012, Rutgers Art Review transitioned from a subscription-based to an open-access, online publication. All fu- ture issues will be published online and made available for download on the RAR website Volumes page and through EBSCO’s WilsonWeb. For more information about RAR, to download previous volumes, or to subscribe to printed volumes be- fore Vol. -

The Hyper Sexual Hysteric: Decadent Aesthetics and the Intertextuality of Transgression in Nick Cave’S Salomé

The Hyper Sexual Hysteric: Decadent Aesthetics and the Intertextuality of Transgression in Nick Cave’s Salomé Gerrard Carter Département d'études du monde anglophone (DEMA) Aix-Marseille Université Schuman - 29 avenue R. Schuman - 13628 Aix-en-Provence, , France e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Salomé (1988), Nick Cave’s striking interpretation of the story of the Judean princess enhances and extends the aesthetic and textual analysis of Oscar Wilde’s 1891 French symbolist tragedy (Salomé), yet it is largely overlooked. As we examine the prior bricolage in the creation of such a hypertextual work, we initiate a captivating literary discourse between the intertextual practices and influences of biblical and fin-de-siècle literary texts. The Song of Songs, a biblical hypotext inverted by Wilde in the creation of the linguistic-poetic style he used in Salomé, had never previously been fully explored in such an overt manner. Wilde chose this particular book as the catalyst to indulge in the aesthetics of abjection. Subsequently, Cave’s enterprise is entwined in the Song’s mosaic, with even less reserve. Through a semiotic and transtextual analysis of Cave’s play, this paper employs Gérard Genette’s theory of transtextuality as it is delineated in Palimpsests (1982) to chart ways in which Cave’s Salomé is intertwined with not only Wilde but also the Song of Songs. This literary transformation demonstrates the potential and skill of the artist’s audacious postmodern rewriting of Wilde’s text. Keywords: Salomé, Nick Cave, Oscar Wilde, The Song of Songs, Aesthetics, Gérard Genette, Intertextuality, Transtextuality, Transgression, Puvis de Chavannes. -

A Grammar of Gyeli

A Grammar of Gyeli Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) eingereicht an der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von M.A. Nadine Grimm, geb. Borchardt geboren am 28.01.1982 in Rheda-Wiedenbrück Präsident der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Jan-Hendrik Olbertz Dekanin der Kultur-, Sozial- und Bildungswissenschaftlichen Fakultät Prof. Dr. Julia von Blumenthal Gutachter: 1. 2. Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: Table of Contents List of Tables xi List of Figures xii Abbreviations xiii Acknowledgments xv 1 Introduction 1 1.1 The Gyeli Language . 1 1.1.1 The Language’s Name . 2 1.1.2 Classification . 4 1.1.3 Language Contact . 9 1.1.4 Dialects . 14 1.1.5 Language Endangerment . 16 1.1.6 Special Features of Gyeli . 18 1.1.7 Previous Literature . 19 1.2 The Gyeli Speakers . 21 1.2.1 Environment . 21 1.2.2 Subsistence and Culture . 23 1.3 Methodology . 26 1.3.1 The Project . 27 1.3.2 The Construction of a Speech Community . 27 1.3.3 Data . 28 1.4 Structure of the Grammar . 30 2 Phonology 32 2.1 Consonants . 33 2.1.1 Phonemic Inventory . 34 i Nadine Grimm A Grammar of Gyeli 2.1.2 Realization Rules . 42 2.1.2.1 Labial Velars . 43 2.1.2.2 Allophones . 44 2.1.2.3 Pre-glottalization of Labial and Alveolar Stops and the Issue of Implosives . 47 2.1.2.4 Voicing and Devoicing of Stops . 51 2.1.3 Consonant Clusters . -

Kenyon Collegian College Archives

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange The Kenyon Collegian College Archives 9-22-1977 Kenyon Collegian - September 22, 1977 Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian Recommended Citation "Kenyon Collegian - September 22, 1977" (1977). The Kenyon Collegian. 970. https://digital.kenyon.edu/collegian/970 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College Archives at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kenyon Collegian by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Mf8llt Colleg Established IS56 3 Volume CV, Number Kenyon College, Gambier, Ohio 43022 Thursday, September 22, 1977 Untangling Council Blasts New Fees; Traffic Woes Backs Social Board Duties By LINDSAY C. BROOKS ' WIN'CEK By CHRIS Student Council Sunday night I ! passed a unanimous resolution revisions effective this Despite new forming a subcommittee to look into in code, traffic i school year the traffic the new registration fee for courses likely continue to i fines shall most dropped after the first two weeks among both of t to rouse feathers students the semester, and discussed Social I 5 and the administration. Arnold Board's function as a financial Director of Security, feels Hamilton, source for fraternity-sponsore- d grievance-provokin- g r that "it's the main activities, as well as the possibility of problem between the a seven-ivee- k break at Christmas. students and my department, and The committee will find out the will probably continue to be so." L philosophy behind the fee structure; P whether it is a handling fee or a Chief Security Officer Arnie One junior expressed strong Hamilton on the job penalty fee. -

AS CRIATURAS EM BAUDOLINO DE UMBERTO ECO: Criação De Um Bestiário Tridimensional

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universidade de Lisboa: Repositório.UL UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES AS CRIATURAS EM BAUDOLINO DE UMBERTO ECO: criação de um bestiário tridimensional João Pedro Reis Rico dos Santos Trabalho de Projeto Mestrado em Desenho Trabalho de Projeto orientado pelo Prof. Doutor Henrique Antunes Prata Dias da Costa 2018 DECLARAÇÃO DE AUTORIA Eu João Pedro Reis Rico dos Santos, declaro que o trabalho de projeto de mestrado intitulada “As criaturas em Baudolino de Umberto Eco: criação de um bestiário tridimensional”, é o resultado da minha investigação pessoal e independente. O conteúdo é original e todas as fontes consultadas estão devidamente mencionadas na bibliografia ou outras listagens de fontes documentais, tal como todas as citações diretas ou indiretas têm devida indicação ao longo do trabalho segundo as normas académicas. O Candidato Lisboa, 31 Outubro 2018 2 RESUMO Propõe-se através deste trabalho a criação de um bestiário tridimensional a partir de “Baudolino” de Umberto Eco, onde se representarão em formato tridimensional através da modelação tridimensional cada uma das criaturas complementando a descrição de Eco com outras obtidas em diferentes bestiários recolhidos. Faz-se em primeiro lugar uma revisão do estado da arte, depois um breve estudo sobre o contexto histórico com particular enfase na queda de Constantinopla integrando- a na geografia fantástica das criaturas da terra de Prestes João. Desenvolve-se a investigação através da coleção de autores relacionados com o tema dos bestiários medievais, com destaque na criação digital de monstros e os seus autores, os casos de Plínio o Velho e das crónicas de Nuremberga. -

English Polyphony and the Roman Church David Greenwood

caec1 1a English Polyphony and the Roman Church David Greenwood VOLUME 87, NO. 2 SUMMER, 1960 . ~5 EIGHTH ANNUAL LITURGICAL MUSIC WORKSHOP Flor Peeters Francis Brunner Roger Wagner Paul Koch Ermin Vitry Richard Schuler August 14-26, 1960 Inquire MUSIC DEPARTMENT Boys Town, Nebraska CAECILIA Published four times a year, Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter. Second-Class Postage Paid at Omaha, Nebraska. Subscription price--$3.00 per year All articles for publication must be in the hands of the editor, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebraska, 30 days before month of publication. Business Manager: Norbert Letter Change of address should be sent to the circulation manager: Paul Sing, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebraska Postmaster: Form 3579 to Caecilia, 3558 Cass St., Omaha 31, Nebr. CHANT ACCOMPANIMENTS by Bernard Jones KYRIE XVI " - .. - -91 Ky - ri - e_ * e - le -i - son. Ky - ri - e_ e - le - i - son •. " -.J I I I I J I I J I j I J : ' I I I " - ., - •· - - Ky-ri - e_ e - le -i - son. Chri-ste_ e - le -i - son. Chi-i-ste_ e - le- i - son.· I ( " .., I I j .Q. .0. I J J ~ ) : - ' ' " - - 9J Chri - ste_ e - le - i - son. Ky - ri - e __ e - le - i - son. " .., j .A - I I J J I I " - ., - . Ky -ri - e_ e - le - i - son. Ky- ri - e_* e -le - i - son. " I " I I I ~ I J I I J J. _J. J.,.-___ : . T T l I I M:SS Suppkmcnt to Caecilia Vol. 87, No. 2 SANCTUS XVI 11 a II I I I 2. -

This Article Explores Umberto Eco's Contribution to the Current Debate

9-di martino_0Syrimis 12/19/12 2:36 PM Page 189 Between “n ew Realism ” and “w eak thought ”: umBeRto eco ’s “n egative Realism ” and the discouRse of late PostmodeRn Impegno loRedana di maRtino Summary: the recent theory of a return of realism has sparked a lively and somewhat heated debate among contemporary italian thinkers, gen - erating a split between the supporters of the philosophy of weak thought, and those who argue for an overcoming of postmodernism and the devel - opment of a new philosophy of realism. this article explores umberto eco’s contribution to this debate, focusing both on eco’s theory of “neg - ative realism” and on his latest historiographic metafiction. i argue that while eco’s recent theory further distances the author from the philoso - phy of weak thought, it does not call, as does maurizio ferraris’s philos - ophy of new realism, for an overcoming of postmodernism. instead, fol - lowing the outward shift that is typical of late postmodern impegno , eco’s later work creates a critical idiom that more clearly uses postmodernist self-awareness as a strategy to promote self-empowerment and social emancipation . this article explores umberto eco’s contribution to the current debate on the return of realism in order to shed light on the author’s position in the dis - pute between realisti— the supporters of the so-called philosophy of new realism —such as maurizio ferraris, and debolisti —the supporters of the postmodern philosophy of weak thought—such as gianni vattimo. my goal is to show that, while eco’s recent theory of “negative realism” further dis - tances the author from the philosophy of weak thought, it does not argue, as does ferraris’s philosophy of new realism, for an overcoming of postmod - ernism. -

Umberto Eco Book Review.Fm

Mundus Senescit: Umberto Eco recreates the Middle Ages Umberto Eco’s recent historical novel Baudolino opens with a sort of gibberish combination of Latin, German, Italian, and English, a gleeful combination of inside jokes, puns, and scholarly winks and nods. The tale, written on top of an earlier history that has been scratched off the parchment but occasionally peaks through, is a story in a story in a story on a story. If that sounds complicated—well, it is. Trickster Baudolino, an unreliable narrator by his own unreliable report, tells his long life story to Niketas, an historian whom Baudolino hopes will be able to give shape and meaning to an otherwise almost random series of events and decisions. From the very beginning, Eco is playing with myth, truth, history, and storytelling—and tackling a project far more lofty than Niketas’. With the recent publication of Baudolino, Umberto Eco returns to writing fiction set in the Middle Ages—and creates an ultimate symbol for medieval thought and history, in its own time and in our own. Eco’s concern for medieval philosophy, present in both his popular and scholarly works, is in fact a sort of nostalgia for a time now much maligned and misunderstood, a forgotten kingdom of intellect and imagination. Very much a realist, Eco never suggests we can— or should—return to a medieval mindset (Society for Creative Anachronism aside, no one who truly knows the Middle Ages could ever wish to live it over.) But in medieval thought he finds an elegant system, though one that was obsessed with its own eventual irrelevance and decay.