The Retractable Airplane Landing Gear and the Northrop "Anomaly": Variation-Selection and the Shaping of Technology Author(S): Walter G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northrop Gamma 2A

Northrop Gamma 2A History: John Northrop began work as a garage mechanic with little formal education but, like many of his generation, a fascination with flight. As a mechanic he acquired the experience and knowledge that made him a skilled and innovative designer in later life. He worked for the Loughead Brothers when they started building aeroplanes in California and designed a two seat sports aeroplane for them. A couple of years later he went over to Douglas and was involved in the design of the Douglas World Cruiser before returning to what was then Lockheed where he designed the Lockheed Vega. He wanted to work on more innovative designs but Lockheed didn’t so he moved on. Circumstances saw him involved with a number of companies including, from 1932 to 1937, the Northrop Corporation which was fifty-one per cent owned by Douglas. During that time he designed and built the Northrop Gamma. The Gamma was a continuation of earlier design ideas demonstrated in the Lockheed Vega and the Northrop Alpha, both advanced designs for their time with monoplane wings of multicelular aluminium sheets that were the precursor of the wings of such important designs as the Douglas DC-3 and the Douglas SBD. The Gamma combined that style of wing with a powerful engine and a streamlined metal fuselage. The first Gammas were built to special orders as record breaking and research aeroplanes, later ones included military and commercial versions. In all fifteen versions were finally manufactured, eleven of them with only one being made, a couple with twenty or so and the final version, the 2F of which there were 102, appears to have little in common with its earlier versions and served as a light attack and training aeroplane in the early days of World War II. -

Tejas Inducted Into 45 Squadron of IAF BOEING

www.aeromag.in July - August 2016 Vol : X Issue : 4 Aeromag10 years in Aerospace Asia Tejas inducted into 45 squadron of IAF BOEING A Publication in association with the Society of Indian Aerospace and Defence Technologies & Industries D. V. Prasad, IAS AMARI 280 x 205_Layout 1 20/07/2016 10:36 Page 1 The metals service provider linking India with the UK n ON-TIME, IN-FULL deliveries throughout the whole of Asia from one of the world’s largest metals suppliers n Key supplier to high-tech industries including aerospace, defence and motorsport n Reliable, cost effective supply of semi-finished metal products to near net shape... in plate, bar, sheet, tube and forged stock n From an extensive specialist inventory: aluminium, steels, titanium, copper and nickel alloys n Fully approved by all major OEM's and to ISO 9001:2008, AS9100 REV C accreditations Preferred strategic supply partner to India's aerospace manufacturing sector. Tel: +44 (0)23 8074 2750 Fax:+44 (0)23 8074 1947 [email protected] www.amari-aerospace.com An Aero Metals Alliance member EOS e-Manufacturing Solutions Editorial A Publication dedicated to Aerospace & Defence Industry nduction of Tejas, India’s indigenously developed Light Combat Aircraft, into the Editorial Advisory Board I‘Flying Daggers’ Squadron of Indian Air Force is Dr. C.G. Krishnadas Nair a matter of great pride for our nation. It marks the Air Chief Marshal S. Krishnaswamy (Rtd) fruition of a national dream and a milestone to be PVSM, AVSM, VM & Bar Air Marshal P. Rajkumar (Rtd) celebrated by the Indian Aeronautical community. -

TWA, Departs the World’S Gers, Not Mail, Unlike Most Other Airlines Skies in Almost the Same Industry Envi- PART I in Those Days

rans World Airlines, with one of the month; copilots, $250. most recognized U.S. airline sym- TAT was developed to carry passen- bols, TWA, departs the world’s gers, not mail, unlike most other airlines skies in almost the same industry envi- PART I in those days. TAT’s transcontinental ronment in which it came into being— As TWA ended its 71 years of air/rail service would take passengers the end of an unfettered period of ex- cross-country in 2 days instead of 3, as pansion marked by consolidation of air- continuous operations, it was rail-only travel required. On the west- lines. Born of a 1930 merger, TWA had the United States’ longest to-east schedule, passengers would most of its assets purchased by Ameri- board a Ford Trimotor at Los Angeles can Airlines on April 9, 2001, to end flying air carrier. at 8:45 a.m. (PST), deplane at Clovis, TWA’s run as the longest-flying air car- N.M., at 6:54 p.m. (MST) for a night rail By Esperison Martinez, Jr. rier in U.S. commercial aviation. Still, trip to Waynoka, Okla., via the Topeka Contributing Editor its 71 years of flying millions of passen- & Santa Fe Railroad, followed by an 8- gers throughout the world, of record- hour 8-minute Trimotor flight to Colum- ing achievements that won’t be quickly bus, Ohio, then onto the Pennsylvania duplicated, of establishing sterling stan- manager of NAT, became TAT vice- Railroad to arrive in New York City the dards of operations, safety, and profes- president. -

Film Archive Online

NATIONAL AEROSPACE LIBRARY Film Archive Online On 30 May 1935 a particularly distinguished audience gathered at the Science Museum in London to listen to Donald Wills Douglas – founder of the Douglas Aircraft Company – deliver the Royal Aeronautical Society’s 23rd Wilbur Wright Memorial Lecture entitled ‘The Development and Reliability of the Modern Multi-Engine Air Liner’. The lecture did not begin until 9.15pm in the late evening – as it had been preceeded by the annual Council Dinner – and following the lecture Mr Douglas showed a film which as recorded in the Society’s Journal of November 1935 he described Above: Douglas World as follows: Cruiser. The ‘Chicago’ “ ... I am hopeful that the moving picture film photographed over Asian I am about to have shown you will so engross waters during the historic you attention that any defects in my talk will be 1924 flight circumnavigating the globe. unnoticed. As might be said in Hollywood, film by Right: A screen shot of the Fox, Warner and others – sound effects by Douglas! Miles M39B Libellula from the The film to be shown is somewhat historical in film ‘The Miles Libellula– a that we shall see at the start the first really successful New Basic Design’. airliners, namely, the early Fokker and Ford tri- Below: Donald Wills Douglas engined planes ....” Sr, 1892-1981, c.April 1939. RAeS (NAL). Entitled ‘Principal Air Transports in America ... Prepared for Donald W. Douglas’ the two-reeler 20 minute black-and-white silent film began with film footage of Fokker single and tri-motored aircraft including the Fokker F.VII ‘Josephine Ford’ Byrd Arctic Expedition, 1928 Pan American Airways US/ This very film – which has lain unseen for over Cuban Mail Delivery Fokker F-10 ‘De Luxe’ (with 80 years – has recently been digitised by the Charles Lindbergh), 1928 Richard E Byrd’s Antarctic National Aerospace Library and is among many flight, Sir Charles Kingsford Smith’s ‘Southern Cross’ highlights from its historic film archive which can aircraft and Ford Tri-Motor of Scenic Airways. -

Daniel Egger Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c87w6jb1 Online items available Daniel Egger papers Finding aid prepared and updated by Gina C Giang. Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © Finding aid last updated June 2019. The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Daniel Egger papers mssEgger 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Daniel Egger papers Inclusive Dates: 1927-2019 Collection Number: mssEgger Collector: Egger, Daniel Frederic Extent: 3 boxes, 1 oversize folder, 1 flash drive, and 1 tube (1.04 linear feet) Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Fax: (626) 449-5720 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The Daniel Egger papers include correspondence, printed matter, and photographs related to Daniel Egger’s career in the aerospace industry. Language of Material: The records are in English and Spanish. Access Collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, please go to following web site . NOT AVAILABLE: The collection contains one flash drive, which is unavailable until reformatted. Please contact Reader Services for more information. RESTRICTED: Tube 1 (previously housed in Box 1, folder 1). Due to size of original, original will be available only with curatorial permission. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

Con El Citation Latitude Cessna Llega a Los 7.000 Jets PÁGINA 19 02 Aeromarket AGOSTO 2016 AGOSTO 2016 Aeromarket 03 EDITORIAL

AÑO XXV - Nº 210 Argentina, AGOSTO 2016 $ 30 www.aeromarket.com.ar @AeromarketAR INFORMACIÓN Y ANÁLISIS DE LA AVIACIÓN CIVIL Reportaje: Fernando Sivak Director Provincial de Aeronavegación Oficial y Planificación Aeroportuaria PÁGINA 6 Los 100 años de Boeing PÁGINA 12 Con el Citation Latitude Cessna llega a los 7.000 jets PÁGINA 19 02 Aeromarket AGOSTO 2016 AGOSTO 2016 Aeromarket 03 EDITORIAL “Confieso que no profeso a la libertad de prensa ese amor completo e instantáneo que se otorga a las cosas soberanamente buenas por su naturaleza. La quiero por consideración a los males que impide, más que a los bienes que realiza”. Alexis de Tocqueville La democracia en América Una “empresa” que se debería auditar Por Luis Alberto Franco ace unas semanas el director de “privatizadas” de los '90, que sigue un extraño o gabela a los trabajadores independientes que Vialidad Nacional señaló que la derrotero sin ningún contratiempo. No sólo realizan tareas en espacios alquilados por H obra pública tuvo un 50% de sobre- sobrevivió al gobierno de Carlos Menem –el empresas que pagan su canon, lo cual además precio; por diversos medios nos enteramos creador del monopolio artificial– sino a de ser una suerte de tributo, es una doble sobre corrupción en áreas del Estado y de Fernando de la Rúa, Eduardo Duhalde, imposición. encubrimientos que nos indignan como con- Néstor Kirchner y su esposa, la abogada de Pero los raros privilegios no quedan ahí, ya tribuyentes y avergüenzan como ciudadanos. éxito. Además, es la única que mantuvo sus que no se sabe qué parte de las obras realizadas Sólo pocos quisieron ver lo que pasó durante tarifas dolarizadas y una de las pocas que no en los aeropuertos bajo concesión han sido demasiado tiempo en la anterior gestión de cumplió con las condiciones de concesión a las inversiones reales de AA2000, lo cual siempre gobierno. -

Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

DIRECTORY HIGHLIGHTS ENGLISH Food Service SOUTHWEST AIRLINES Baby Care Station FLIGHT LINE CAFÉ Welcome Center Skylab Orbital Workshop For Kids: How Things Fly Gallery SPACE RACE HOW THINGS FLY Gallery 114 Gallery 109 Gift Shop Elevator Men’s Restroom A C Simulators Escalator Women’s Restroom Apollo Lunar Module Touchable Moon Rock BOEING MILESTONES OF FLIGHT HALL BOEING MILESTONES OF FLIGHT HALL Gallery 100 Gallery 100 Jefferson Drive at 4th and 7th Streets, SW Drive at 4th and 7th Streets, Jefferson Washington, DC 20560 202-633-2214 | airandspace.si.edu Open Daily 10:00–5:30 Closed December 25 Tickets Stairs Family Restroom B D Theater Telephones Emergency Exits BIG CHANGES ARE IN THE AIR We are in the midst of a major project to transform the Museum for the future. The project includes revitalization ATM Water Fountain of the exterior and a comprehensive reimagining of all the Floor Level Hanging Hanging exhibitions. To learn more about the project and how you Artifacts Artifacts Artifacts can get involved, visit airandspace.si.edu/reimagine. FIRST FLOOR Entrance Temporarily Closed Hooker Telescope 1909 Wright Beech Model 17 Observing Cage Herschel Military Flyer Staggerwing Curtiss J-1 Robin Telescope Curtiss Ole Miss Hubble Cessna 150 Blended Wing Model D EXPLORE DeHavilland GOES Body Model Lockheed XP-80 Hughes H-1 PHOEBE WATERMAN HAAS Space Satellite “Headless Telescope THE UNIVERSE DH-4 Lockheed Pusher” Lulu Belle PUBLIC OBSERVATORY Mirror U-2 C DESIGN HANGAR Star Trek 111 SIMULATORS Enterprise Blériot XI Ecker Messerschmitt Me -

General Files Series, 1932-75

GENERAL FILE SERIES Table of Contents Subseries Box Numbers Subseries Box Numbers Annual Files Annual Files 1933-36 1-3 1957 82-91 1937 3-4 1958 91-100 1938 4-5 1959 100-110 1939 5-7 1960 110-120 1940 7-9 1961 120-130 1941 9-10 1962 130-140 1942-43 10 1963 140-150 1946 10 1964 150-160 1947 11 1965 160-168 1948 11-12 1966 168-175 1949 13-23 1967 176-185 1950-53 24-53 Social File 186-201 1954 54-63 Subject File 202-238 1955 64-76 Foreign File 239-255 1956 76-82 Special File 255-263 JACQUELINE COCHRAN PAPERS GENERAL FILES SERIES CONTAINER LIST Box No. Contents Subseries I: Annual Files Sub-subseries 1: 1933-36 Files 1 Correspondence (Misc. planes) (1)(2) [Miscellaneous Correspondence 1933-36] [memo re JC’s crash at Indianapolis] [Financial Records 1934-35] (1)-(10) [maintenance of JC’s airplanes; arrangements for London - Melbourne race] Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1934 (1)-(7) 2 Granville, Miller & DeLackner 1935 (1)(2) Edmund Jakobi 1934 Re: G.B. Plane Return from England Just, G.W. 1934 Leonard, Royal (Harlan Hull) 1934 London Flight - General (1)-(12) London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables General (1)-(5) [cable file of Royal Leonard, FBO’s London agent, re preparations for race] 3 London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Fueling Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Hangar Arrangements London - Melbourne Air Race 1934 Cables Insurance [London - Melbourne Flight Instructions] (1)(2) McLeod, Fred B. [Fred McLeod Correspondence July - August 1934] (1)-(3) Joseph B. -

Propulsion & Performance

The Air Transport Revolution: A Selective Review Dr. Richard P. Hallion Aero 2050 Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board 11 October 2017 …The Aerospace Revolution… • 1903 1st Powered, Sustained, & Controlled Flight • 1926 1st Liquid Fuel Rocket Flight • 1935 1st Intercontinental Airliner • 1939 1st Turbojet Airplane • 1943 1st Ballistic Missile • 1949 1st Jet Transport • 1957 1st Earth Satellite • 1958 1st Transatlantic Jet Travel • 1969 1st Wide-body “Jumbo Jet” (the B-747) • 1981 1st Reusable Routine Space Access System • 1989 1st GPS Block II Satellite launch • 2001 1st Global-Ranging Intercontinental RPA • 2010 1st Thermally Balanced Hypersonic Scramjet Aviation Progression: One View… PISTON FIGHTERS 3.0 PISTON AIRLINERS and 2.5 BOMBERS 2.0 ROCKET AIRCRAFT JET FIGHTERS 1.5 Plateau JET AIRLINERS and Mach Number Mach 1.0 BOMBERS 0.5 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 …A Merger of Revolutions… …an ostensible “Plateau,” but a 3.0 revolution in capabilities… 2.5 (JET FIGHTERS) 2.0 COMPOSITES; LARGE FANJET; T/W = 1+; DFBW; STEALTH; 1.5 AND NEXT? SUPERCRITICAL WING; GPS; Mach Number Mach 1.0 UAV; SENSORS; C4ISR; ETC. (JET AIRLINERS) 0.5 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 …From Subsonic to Supersonic… Deperdussin Monocoque Douglas DC-1 Boeing 707 Lockheed Blackbird Photographs courtesy The Boeing Company, NASA Dryden Flight Research Center, and the Musée de l’Air et l'Éspace, Le Bourget 17 December 1903 …Powered, Sustained, and Controlled Flight… Aero 2050 17 December 1903 …Powered, Sustained, and Controlled Flight… Inherently unstable design Overemphasis on control over stability Too wedded to a single design concept Aero 2050 Deperdussin Monocoque Racer, 1912-1913 AFHRA 8 Zeppelin-Staaken [Rohrbach]E.4/20 Sep-Oct 1920 Library of Congress 9 …Birthing the Safe & Economical Airliner… Lockheed Vega Boeing Monomail Boeing 247 Douglas DC-1 The DC-1: America’s First “Scientific” Airplane… Douglas DC-1 on early test flight, 1933 NASM Photo Aero 2050 In contrast…(Handley Page H.P. -

Compiled by Lincoln Ross Model Name/Article Title/Etc. Author

compiled by Lincoln Ross currently, issues 94 (Nov 1983) thru 293 (Jan 2017), 296 (Jul, 2017) thru 299 (Jan/Feb 2018), also 36, 71 and 82 (Jan 1982) I've tried to get all the major articles, all the three views, and all the plans. However, this is a work in progress and I find that sometimes I miss things, or I may be inconsistent about what makes the cut and what doesn’t. If you found it somewhere else, you may find a more up to date version of this document in the Exotic and Special Interest/ Free Flight section in RCGroups.com. http://www.rcgroups.com/forums/showthread.php?t=1877075 Send corrections to lincolnr "at" rcn "dot" com. Also, if you contributed something, and I've got you listed as "anonymous", please let me know and I'll add your name. Loans or scans of the missing issues would be very much appreciated, although not strictly necessary, since, after issue 70, I'm only missing 294 and 295. Before issue 71, I only have pdf files. Many thanks to Jim Zolbe for a number of scans and index entries. His contributions are shaded pale blue. In some cases, there are duplications that I've kept issuedue to more information or what I think is a better entry date, issu usually e first of model name/article author/designe span no. two title/etc. r in. type comment German flyers with shattered prop surrender 36 cover to British flyer with one kill to his credit already, no date Surrender in the Air Jim Hyka na illustration drawing Shows old find the balloons drawing and contest from Flying Aces Magazine with 36 revised prizes and threats if you can find the contest, hidden balloons. -

B&W Real.Xlsx

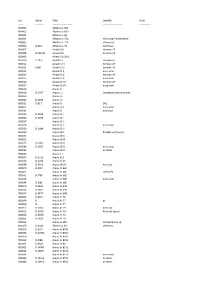

NO REGN TYPE OWNER YEAR ‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ X00001 Albatros L‐68C X00002 Albatros L‐68D X00003 Albatros L‐69 X00004 Albatros L‐72C Hamburg Fremdenblatt X00005 Albatros L‐72C striped c/s X00006 D‐961 Albatros L‐73 Lufthansa X00007 Aviatik B.II German AF X00008 B.558/15 Aviatik B.II German AF X00009 Aviatik PG.20/2 X00010 C.1952 Aviatik C.I German AF X00011 Aviatik C.III German AF X00012 6306 Aviatik C.IX German AF X00013 Aviatik D.II nose view X00014 Aviatik D.III German AF X00015 Aviatik D.III nose view X00016 Aviatik D.VII German AF X00017 Aviatik D.VII nose view X00018 Arado J.1 X00019 D‐1707 Arado L.1 Ostseebad Warnemunde X00020 Arado L.II X00021 D‐1874 Arado L.II X00022 D‐817 Arado S.I DVL X00023 Arado S.IA nose view X00024 Arado S.I modified X00025 D‐1204 Arado SC.I X00026 D‐1192 Arado SC.I X00027 Arado SC.Ii X00028 Arado SC.II nose view X00029 D‐1984 Arado SC.II X00030 Arado SD.1 floatplane @ (poor) X00031 Arado SD.II X00032 Arado SD.III X00033 D‐1905 Arado SSD.I X00034 D‐1905 Arado SSD.I nose view X00035 Arado SSD.I on floats X00036 Arado V.I X00037 D‐1412 Arado W.2 X00038 D‐2994 Arado Ar.66 X00039 D‐IGAX Arado AR.66 Air to Air X00040 D‐IZOF Arado Ar.66C X00041 Arado Ar.68E Luftwaffe X00042 D‐ITEP Arado Ar.68E X00043 Arado Ar.68E nose view X00044 D‐IKIN Arado Ar.68F X00045 D‐2822 Arado Ar.69A X00046 D‐2827 Arado Ar.69B X00047 D‐EPYT Arado Ar.69B X00048 D‐IRAS Arado Ar.76 X00049 D‐ Arado Ar.77 @ X00050 D‐ Arado Ar.77 X00051 D‐EDCG Arado Ar.79 Air to Air X00052 D‐EHCR -

THE INCOMPLETE GUIDE to AIRFOIL USAGE David Lednicer

THE INCOMPLETE GUIDE TO AIRFOIL USAGE David Lednicer Analytical Methods, Inc. 2133 152nd Ave NE Redmond, WA 98052 [email protected] Conventional Aircraft: Wing Root Airfoil Wing Tip Airfoil 3Xtrim 3X47 Ultra TsAGI R-3 (15.5%) TsAGI R-3 (15.5%) 3Xtrim 3X55 Trener TsAGI R-3 (15.5%) TsAGI R-3 (15.5%) AA 65-2 Canario Clark Y Clark Y AAA Vision NACA 63A415 NACA 63A415 AAI AA-2 Mamba NACA 4412 NACA 4412 AAI RQ-2 Pioneer NACA 4415 NACA 4415 AAI Shadow 200 NACA 4415 NACA 4415 AAI Shadow 400 NACA 4415 ? NACA 4415 ? AAMSA Quail Commander Clark Y Clark Y AAMSA Sparrow Commander Clark Y Clark Y Abaris Golden Arrow NACA 65-215 NACA 65-215 ABC Robin RAF-34 RAF-34 Abe Midget V Goettingen 387 Goettingen 387 Abe Mizet II Goettingen 387 Goettingen 387 Abrams Explorer NACA 23018 NACA 23009 Ace Baby Ace Clark Y mod Clark Y mod Ackland Legend Viken GTO Viken GTO Adam Aircraft A500 NASA LS(1)-0417 NASA LS(1)-0417 Adam Aircraft A700 NASA LS(1)-0417 NASA LS(1)-0417 Addyman S.T.G. Goettingen 436 Goettingen 436 AER Pegaso M 100S NACA 63-618 NACA 63-615 mod AerItalia G222 (C-27) NACA 64A315.2 ? NACA 64A315.2 ? AerItalia/AerMacchi/Embraer AMX ? 12% ? 12% AerMacchi AM-3 NACA 23016 NACA 4412 AerMacchi MB.308 NACA 230?? NACA 230?? AerMacchi MB.314 NACA 230?? NACA 230?? AerMacchi MB.320 NACA 230?? NACA 230?? AerMacchi MB.326 NACA 64A114 NACA 64A212 AerMacchi MB.336 NACA 64A114 NACA 64A212 AerMacchi MB.339 NACA 64A114 NACA 64A212 AerMacchi MC.200 Saetta NACA 23018 NACA 23009 AerMacchi MC.201 NACA 23018 NACA 23009 AerMacchi MC.202 Folgore NACA 23018 NACA 23009 AerMacchi